Over the past few years, three demographic studies of North Carolina and Georgia Revolutionary War pension applicants have been completed (North Carolina militia, North Carolina Line, Georgia). A similar study of South Carolina soldiers who served in the Continental Line, state troops, and militia provides compiled demographic data of those who served in that state, and also affords an opportunity to compare and contrast the compiled demographic data of the three contiguous southernmost states.

South Carolina and Military Organization

The colony of South Carolina in 1770 consisted of seven districts and was the eighth most populous colony in North America. Its population in 1773 was estimated at 175,000 people with 110,000 of those being identified as Black.[1] Between June 1775 and early 1776, the South Carolina Provincial Congress created six regiments, all of which were ultimately raised to the Continental establishment. The first units established in 1775, originally designated state troops, were two regiments of foot and one ranger regiment. Later in the year, a smaller regiment of artillery was formed. In 1776, two rifle regiments were added.[2] These regiments served almost exclusively in South Carolina with limited excursions into Georgia and Florida from 1776 to 1780. All six of these regiments functionally ceased to exist after the capitulation of Charlestown in May 1780.

By April 1781, five new state (light) dragoon regiments were created with three more added by the end of the year. These units have come to be colloquially known as the South Carolina state troops and served generally until the end of 1782, with some units in service until sometime in 1783. The South Carolina militia was originally organized by the South Carolina Provincial Congress into sixteen militia districts with each unit designated a “regiment.” In 1778, these units were reorganized into four brigades. With much of the state under British military control in mid-1780, the militia contracted to two brigades under the command of Gen. Thomas Sumter and Gen. Francis Marion. Ultimately, a third brigade was added commanded by Gen. Andrew Pickens. Unlike the South Carolina Continental Line and state troops, the locally based militia units were a presence throughout the war.

Pension Applications

Most Federal Pension Applications began to be filed in 1818 and continued through the late 1830s. Continental soldiers mostly filed pensions under the 1818 and 1828 Pension Acts while those of the militia and state troops came after the Pension Act of 1832. Generally, the pension applications of Continental soldiers filed under the 1818 and 1828 Acts are shorter and yield less demographic information than those of militia and state troops. Under the 1818 Act, the applicant needed to prove nine months of service or service until the end of the war in a Continental regiment in addition to being indigent or disabled. Under the 1828 Act, the applicant only needed to establish service in the Continental Line until the end of the war. The 1832 Act broadened pension eligibility to all men who served six months or more regardless of whether they were in the militia, state troops, or Continental Line. Applicants from 1832 onward were generally required to answer a series of prescribed questions that began with the applicants’ place and date of birth, their place and method of enlistment (volunteer, draft, or substitute), officers under which they served, discharge information, and the names of people who could verify their service. In only two demographic areas do Continental applications provide more information: on occupations and property.

Over 4,500 pension applications pertaining to South Carolina were reviewed for this work.[3] Of those, 1,376 were identified as men who had served in a South Carolina military unit and provided demographic information about themselves and their military service. Together with those of Georgia and North Carolina, the overall body of demographic data collected from pension applications now includes 6,200 men. While most applications were made by the veterans themselves a substantial minority were filed by widows or next of kin. Unfortunately, the latter were generally not used in this study as the next of kin often provided little detail of their relative’s service. As with the previous studies, the data herein represents a small portion of the total number of men who were in South Carolina service during the war. The analysis, findings, and figures presented here only apply to the data collected from the 1,376 pension applicants and should not be construed to apply to the entire body of South Carolina Revolutionary War soldiers.

A word of further caution is necessary regarding data and descriptions on dates of birth, length of service, and property and land ownership. Pension applicants were likely to be younger because many older soldiers died before their applications could be filed. As the average lifespan in eighteenth century America was between forty-one and forty-seven years of age, it certainly is probable that the men studied here represent the younger range of South Carolina soldiers. Regarding the length of a man’s service, some reported only their fixed term of enlistment while others noted the actual number of months they served. While some men kept records to the day of their service, more often than not they referred to their service in terms of months if not years. Furthermore, by the 1830s, very few pension applicants still had their service and discharge papers if they were even issued them at all. As such, there is considerable uncertainty about the accuracy of the men’s overall time in service. Pension applicants likely served longer because of the six-month minimum requirement to qualify for a pension. As a result, almost every militia applicant reported serving more than six months. Lastly, based on the descriptions of the men’s property and the need-based requirements of the 1820 Pension Act it appears that many of these men (at least at the time of their applications) were at the lower economic strata of American society based on their owning very little if any personal property and/or land.

Places and Dates of Birth

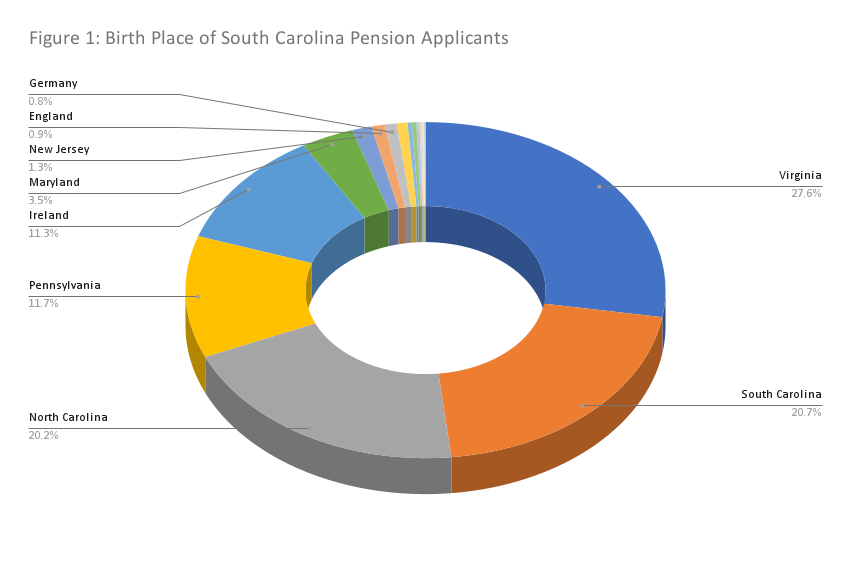

Only 20 percent of the pension applicants who served in a South Carolina military unit were born in the former colony. Virginia is the most common birthplace at 27 percent of all men. South Carolina accounts for the second largest number of places of birth followed by North Carolina, both at 20 percent. Pennsylvania and Ireland account for 11 percent each. South Carolina applicants were born in twelve of the thirteen America colonies and three countries (England, Germany, and Scotland) (Figure 1). The percentage of those “native” born in South Carolina is roughly half the percentage of those born in North Carolina overall (44 percent) but higher than that of Georgia men (6 percent). More broadly, Virginia accounts for 27 to 37 percent of all places of births for men in Carolina and Georgia military units overall. For these three southern states, there is a pattern of decreasing percentages of “native-born” men from north to south.

Almost 14 percent of South Carolina pension applicants were foreign-born. The proportion of Irish births for South Carolina pensioners ranges from twice to five times that of its neighbors. Comparatively, just over 3 percent of North Carolina militia, 6 percent of Continentals, and 8 percent of Georgia’s pensioners were foreign-born. Consistent among those born in Ireland among the pension applicants of the three states is that nearly every one of the men was born in Ulster, Ireland.

The average year of birth of all South Carolina applicants is 1757 (with a median birth year of 1759). This is the same average year as North Carolina militia pension applicants. Overall, Georgia and North Carolina Continental Line average dates of birth were one year earlier, 1756. South Carolina pension applicants’ years of birth range from the year 1730 to 1768. The youngest soldier in the data set was a boy who volunteered at twelve years of age (along with his father) to serve in the South Carolina militia in 1777.[4] Two other boys served when they were thirteen years old, one recalling being drafted while still in school.[5]

Unit Service

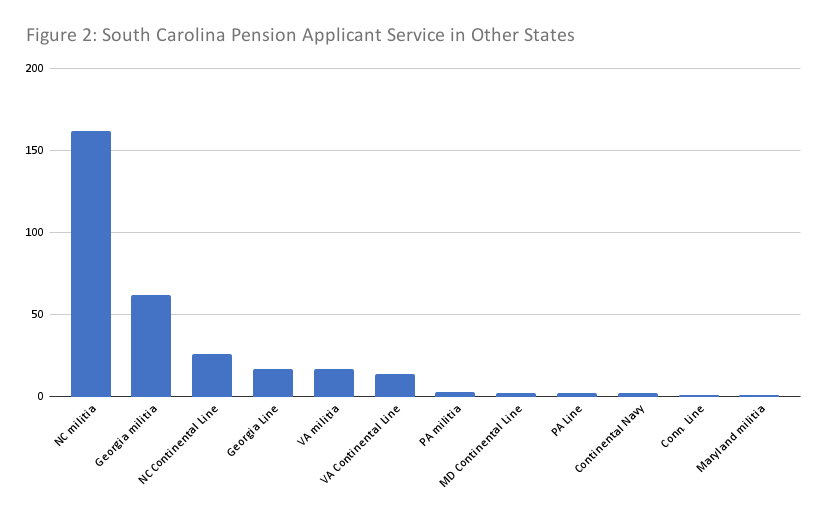

South Carolina pension applicants served in fifteen different military units during the war from seven total states. While most served exclusively in South Carolina units, a substantial minority (20 percent) of the pensioners in this data set served in other states’ military units at least once. By far, the most prominent out-of-state unit for these pension applicants was the North Carolina militia (Figure 2).

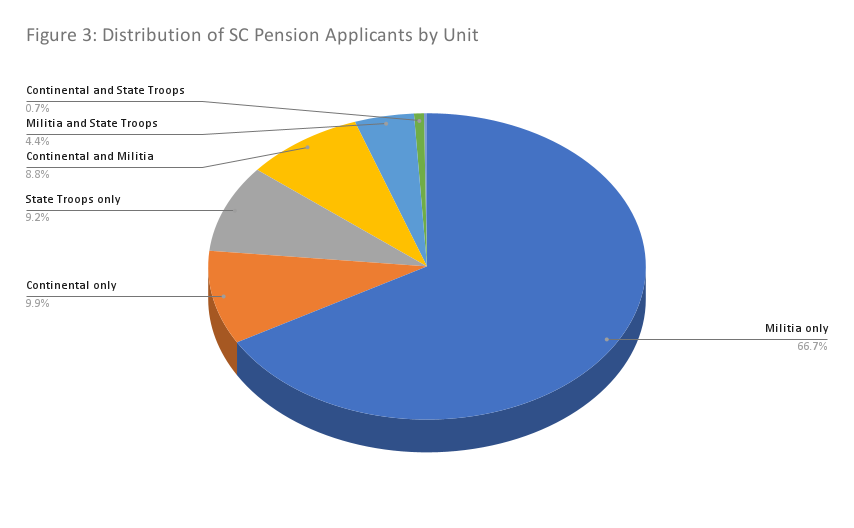

Overall, among all South Carolina pension applicants, most of the men (approximately 85 percent) served in only one of the state’s three militia units. About two-thirds of all men served in the militia only. Roughly 10 percent served in the Continental Line and 9 percent served in the state troops exclusively. A tiny fraction (three total) served in all three: the Continental Line, state troops, and militia (Figure 3).

About 11 percent of men enlisted in South Carolina service outside the state. The vast majority of these men were recruited during early 1781 in the piedmont-backcountry of North Carolina for service in the newly formed South Carolina Light Dragoon regiments. Certainly, the most unique place of enlistment for South Carolina service was in Amsterdam where an English man entered service on the frigate South Carolina. For his pension application he referenced his rather detailed diary of his time on board the ship.[6]

Types of Service

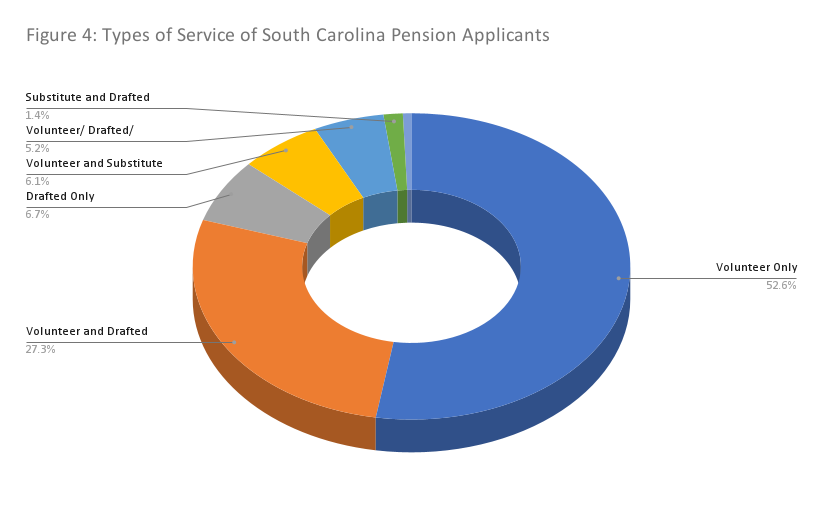

The vast majority of South Carolina pension applicants volunteered at least once for military service. Approximately 91 percent of all men reported volunteering at least once during the war by joining a militia unit or substituting for another man. The largest contingent (52 percent) noted their service as volunteers only. The next largest grouping were those who volunteered and were drafted for militia service (27 percent). While most men volunteered, a substantial minority (40 percent) were drafted at least once. A smaller fraction served as substitutes (12 percent) during the war. An even smaller fraction (5 percent) did all three: volunteered, were drafted, and served as substitutes (Figure 4).

Length of Service and Number of Deployments

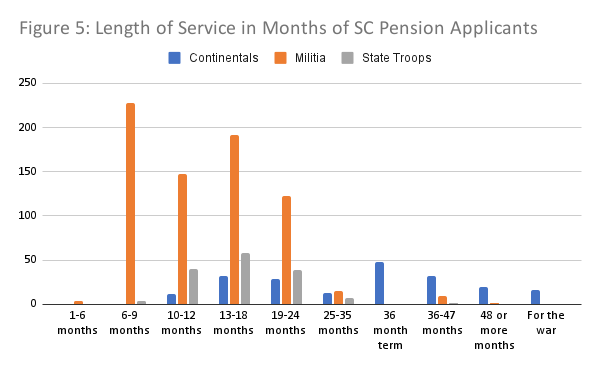

Compiling the length of many pension applicants’ service is difficult with any accuracy as many men gave only approximate accounts of the time they served. While some men provided a list of the day and date of their enlistments, others merely listed the number of years they served. About 80 percent of men provided at least rough indications of how many months they served. The patterns of South Carolina applicants’ lengths of service are consistent with those of North Carolina and Georgia. Militiamen generally served more terms for shorter time frames (generally a three-month term). Roughly 78 percent of South Carolina militia pension applicants served between six and eighteen months during the war. Among all South Carolina militia, the most prevalent time of service was six to nine months overall, accounting for 31 percent of all militiamen. Continental soldiers serving one thirty-six-month term is most prevalent followed by those men who by most accounts served one or two additional terms in the militia or state troops, adding three to nine months to their three-year term of service (Figure 5).

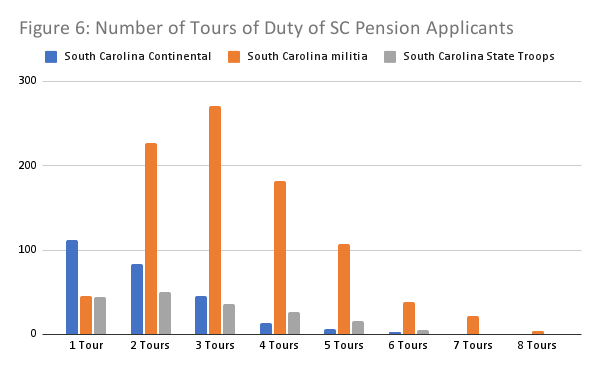

Pension applicants generally provided the number of deployments or tours of duty they served. Overall, about 70 percent of South Carolina pension applicants served either two, three or four tours of duty (Figure 6).[7] Comparatively, while slightly more South Carolina pension applicants served in more than one tour than North Carolina and Georgia men, the overall numbers are not substantially different. The Continental soldiers of all three states generally enlisted once per man while the majority of militia and state troops served three tours of duty.

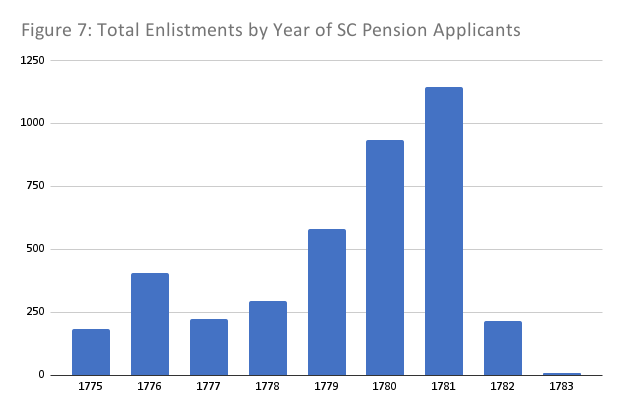

The year 1781 stands out amongst South Carolina pension applicants with 1,145 total enlistments (Figure 7).[8] About 68 percent of all South Carolina pension applicants served at least one term of duty during 1781. Approximately 20 percent of those that served in 1781 served two or more terms or enlistments, the vast majority of these being militiamen.

Battles and Skirmishes

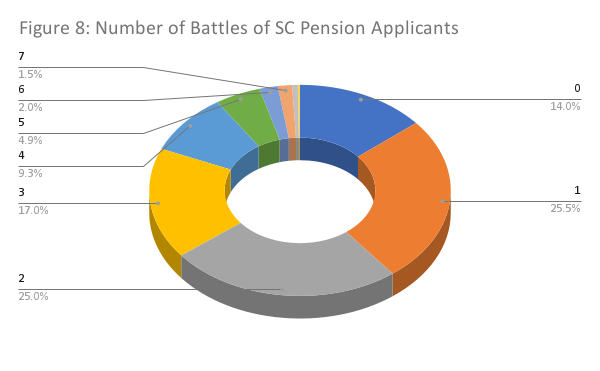

South Carolina pension applicants reported fighting in at least ninety-five named battles or skirmishes during the war. This number is certainly low, as approximately 20 percent of all pension applicants reported unnamed (and often undated) skirmishes with “Tories” and/or Native Americans. A very high percentage of South Carolina pension applicants (86 percent) reported being in a battle or skirmish during the war. Overall, most South Carolina pension applicants (67 percent) fought in one to three battles or skirmishes (Figure 8). While the number of battles or skirmishes as a percentage is roughly the same as for Georgia men overall, it is more than North Carolina men overall. Somewhat similarly, the percentage of men with battle experience is higher for South Carolina pension applicants than North Carolina pension applicants (68 percent of North Carolina militia and 75 percent of Continentals) and those from Georgia (72 percent).

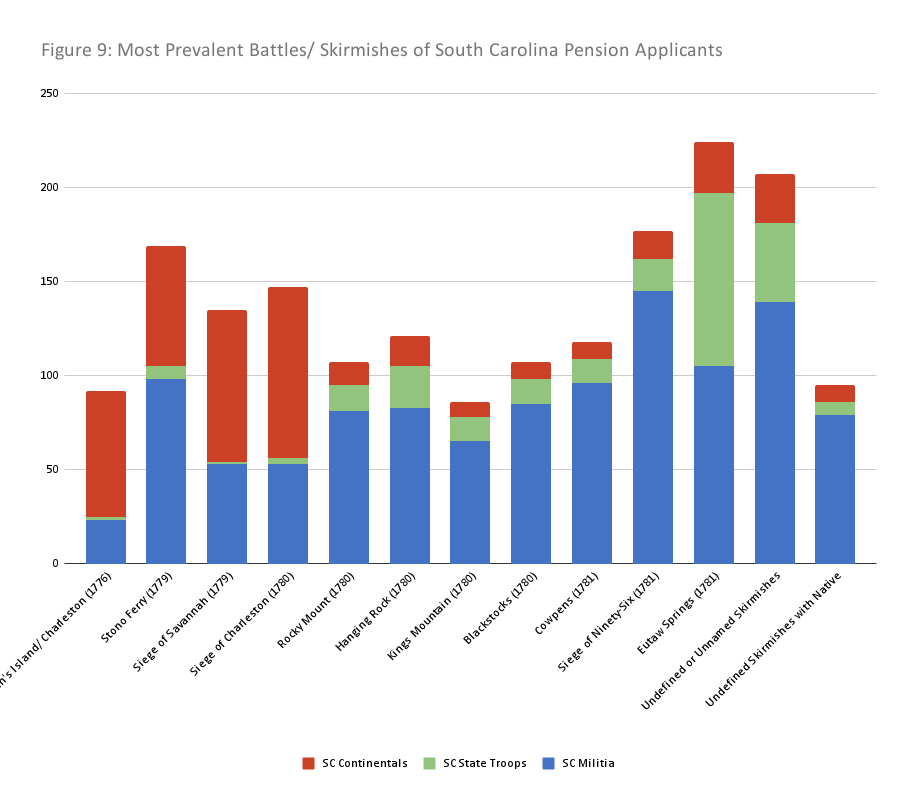

Eleven battles encompassing a period from mid-1776 to late 1781 are the most reported among South Carolina pension applicants. All but one of them (the Siege of Savannah in 1779) were fought within the borders of South Carolina. Most, but not all, of the largest battles within the state are most prominent: Charlestown (1776 and 1780), Stono Ferry, Cowpens, Ninety-Six, and Eutaw Springs. Missing from this list is the Battle of Camden where only twenty-six pension applicants reported their involvement in the battle.[9] Conversely, several battles that were relatively small in scale were well-attended by South Carolina pension applicants. Battles at Rocky Mount, Hanging Rock, Kings Mountain, and Blackstocks figure almost as prominently as the more well-known battles (Figure 9).[10]

Personal accounts of the fierce and bloody engagement at Eutaw Springs are well-reported among pension applicants. Many men stated being wounded at the battle by musket balls and bayonets. One man reported that of his platoon of twelve men, five survived the battle.[11] Another man was one of fourteen men who tried to free Lt. Col. William Washington after he was captured; ten of the men died in the charge.[12]

Possessions and Occupations

Approximately 29 percent of South Carolina pension applicants who listed their possessions owned land at the time they made their pension applications. This number is higher than Georgia (18 percent) and North Carolina (25 percent). About 6.5 percent of South Carolina pension applicants reported owning enslaved people at the time they made their applications. The percentage who owned enslaved people is lower than Georgia applicants (11 percent) but higher than North Carolina Continentals (2.4 percent). This figure could be considered low given that 25 percent of households in 1860 owned enslaved people. However, this figure is higher than the overall individual rate of ownership (4.9 percent).[13] Some indications that both land and enslaved person ownership was low can be seen in some applicants selling their land or enslaved people before filing for their pensions. One man’s four enslaved people died before his pension was filed, and two others reported selling their land and enslaved people before filing their pension applications.[14]

Less than 10 percent of all South Carolina pension applicants provided their occupation. An overwhelming majority of these men (79 percent) listed their occupation as farmers. The percentage of farmers among South Carolina applicants is 11 to 14 percent higher than those for the adjoining states. Similar to North Carolina, laborer and blacksmith are the second and third most prevalent occupations at about 9 percent. Other occupations include, in order of rank: weaver, mason, teacher, shoemaker, saddler, debt collector, millwright, glazer, and minister.

Free Men of Color

Free men of color comprise about 1.9 percent of all men in the South Carolina pension applications data used for this work. This number is considerably higher than the 0.7 percent of total “other” free South Carolinians of color represented in the 1790 Census. Comparatively, South Carolina had a greater representation of free men of color in their military units than Georgia (at less than one percent) but fewer than North Carolina with 2.5 percent of its militia and 7 percent of its Continental Line’s pension applicants who were free men of color. Two Virginia size rolls (taken at the time of enlistment) roughly correspond with the North Carolina proportions of “other” free men’s military service. These rolls indicate a range of 5.8 percent to 9.5 percent of 2,000 Virginia Continental Line soldiers who were men of color or African descent. With this data from Virginia, there appears to be a pattern of decreasing representation of free men of color in Revolutionary War military service from north to south at the state level.

At least three of the few free men of color (and their families) in the data set for this work faced challenges in obtaining their pensions. One man’s wife and children would almost certainly not benefit from his service because they were enslaved people, which appears to have not been allowed in the state where it was filed. Similarly, another man’s wife could not receive his pension because she was an enslaved person even though her owner agreed to free her. The 1859 claim was finally rejected because the laws of Alabama would not permit her manumission.[15] One descendent, filing for his father’s pension in 1844, missed a potential decade or more of pension payments because he was under the impression that his parents being “free persons of color” didn’t qualify for a pension.[16]

“Sumter’s Law”

In March 1781, Gen. Thomas Sumter announced a plan to raise several regiments of light dragoons for ten-months service. “Sumter’s Law,” as it became known, proposed to compensate the dragoons with enslaved people confiscated from Loyalists.[17] The implementation was problematic from its start as the plan never yielded enough soldiers to fill the new regiments and most of the men never received their promised payment of an enslaved person if any compensation at all.

Of the 200 pension applications of these state troops, very few (10 percent) mentioned enslaved people as payment for their service. While it has been assumed that some or many men joined due to the promised payment of an enslaved person for their service, no man in his pension specifically noted that he enlisted because of the promised bounty. However, one man did note that he stayed in service so he would not lose his claim to payment. While every man in this service was due at least one enslaved person as pay by rank, only about 5 percent of these state troops in their pension applications reported being “paid” with an enslaved person. Estimates from 1782 pay rolls range considerably higher, generally documenting between 15 and 33 percent of men who received their “payment.” The most substantial portion of these state troops (28 percent) in their pension applications noted selling their claim to an enslaved person after the war or receiving an “indent” for a cash payment at a later date. Interestingly, there are at least three free men of color who served in the state troops and were thereby eligible to be “paid” with an enslaved person. From the available payrolls, it appears two free men of color received an enslaved person for service in the state troops. By the time of their filing, neither man reported an enslaved person or any other possessions in their pensions.[18]

Prisoners of War

Almost 21 percent of all South Carolina pension applicants were made prisoners of war. Among all prisoners, 43 percent were captured at the surrender of Charlestown in 1780. Of these prisoners, 34 percent managed to escape their captivity. About one-quarter of South Carolina Continentals who escaped Charlestown after the surrender later returned to service in the militia and, in a few cases, the state troops. Similar to other Continental soldiers captured at Charlestown, several South Carolina Continentals joined, were coerced, or perhaps were even forced into British army or naval service in 1781.[19] At least three men (and likely a fourth) noted they were taken to Jamaica as “prisoners” or “put on shore” in Canada “after the peace.” Consistent among the statements of these men in their pension applications (and those from other states) is the careful omission of their British army service.

Location of Pension Application

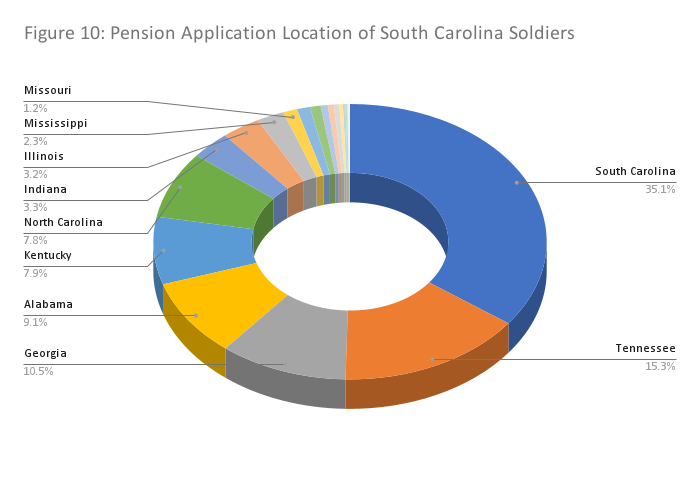

Every South Carolina pension applicant in this data set provided the county and state where they filed their claim. Most pension applicants (65 percent) who served in a South Carolina unit did not file their pensions in South Carolina. By the 1820s and 1830s, these men and their families had moved to eighteen states and Washington, D.C. (Figure 10). The distribution and patterns of movement are very similar to those documented for Georgia and North Carolina. The balance of these families moved (excepting the states where they served) westward to the future states of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Alabama. Almost 3 percent of all South Carolina pension applications were filed in states west of the Mississippi. It is probable, if not a certainty, that a small portion of these men lived in territories outside the United States (at the time) and filed their applications in the nearest recognized court.

Among the three southernmost states and considering places of birth of the men it is clear that American society before, in some cases during and after, the war was exceptionally transitory. The types of movements of William Gaston were not uncommon among pension applicants. Born in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, his family moved to Chester County, South Carolina before the war where he served in the militia. After the war he moved to Kentucky and then to Marion County, Illinois where he died in 1838. Similar to the birth places of pension applicants, there is a corresponding pattern from north to south of the percentage of pension applicants that filed their claim from where they served. Only 35 percent of South Carolina pensioners filed their claims from South Carolina. This is less than North Carolina Continental pensions at 50 percent and North Carolina militia at 39 percent but more than the 31 percent of Georgia pensioners who filed from the states where they served.

Conclusion

Overall, among the three southern states there appear to be more similarities than differences among the assembled data of its pension applicants. Most apparent among the similarities are places of birth, especially those outside of the states where the applicants served. Likewise, the years, duration, and type of service are more similar among the three states than they are dissimilar. There is also certainly overlap among the battles in which the men fought at a broad scale. The locations where the men and their families moved also overlaps considerably. Yet there are also some dissimilarities in service. South Carolina pension applicants appear to have served (slightly) more time, more deployments, and fought in more battles than their neighbors. In the broad context of the war these dissimilarities are not a surprise as South Carolina, much more so than its neighbors, was a focus of British invasion attempts and was the site of significantly more numerous and intensive battles. Conversely, North Carolina soldiers served in greatly more varied locations from New York to Georgia, certainly a contrast to South Carolina and Georgia soldiers who served overwhelmingly in their respective states.

To what extent these three southern states compare and contrast to their northern neighbors is not known. Although efforts are underway to compile and assemble comparable data on northern states, these works are not immediately forthcoming as many, if not most, pension applications from those states have not been transcribed. Perhaps sooner rather than later a comparable comparison and evaluation can be made of southern and northern soldiers of the Revolution. Fortunately, all of the pension applications from Virginia have been completed and are available in online databases. They are the focus of the next iteration of this demographic project.

[1]United States Census Bureau, A Century of Population Growth in the United States: From the First Census of the United States to the Twelfth: 1790-1900, 7, www.census.gov/library/publications/1909/decennial/century-populaton-growth.html.

[2]Richard K. Wright Jr., The Continental Army (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 305-309.

[3]All pension applications used for this and previous studies were found at the Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters website (revwarapps.org/). The vast majority of the pension applications there and used for this work were transcribed by Will Graves and C. Leon Harris.

[4]Pension application of John Brown (W5906).

[5]Pension applications of Josias Sessions (S18202) and David Anderson (S6515).

[6]Pension application of George Fisher (S46036).

[7]The number of tours of duty for Continental and state troops in Figure 6 also includes these men’s militia tours of duty if they served in the militia.

[8]The enlistments by year for Figure 7 are combined for clarity. An attempt was made to separate Continental soldiers from militia and state troops by year, but this proved to be exceptionally difficult.

[9]The Battle of Camden is not even among the top twenty battles most attended by South Carolina pension applicants.

[10]In Figure 9, the Continental soldiers for battles after Charlestown would have served in the militia or state troops. State troops noted before the battle at Ninety-Six were men who would have served previously in the Continental Line or militia.

[11]Pension application of Gustavus Rape (W1318).

[12]Pension application of Charles Smith (W6122).

[13]Joseph T. Glatthaar, Soldiering in the Army of Northern Virginia: A Statistical Portrait of the Troops Who Served under Robert E. Lee (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011), Kindle Edition, 9.

[14]Pension applications of John McCune (38940), David Garrett (38719) and Abraham Kelly (S38891).

[15]Pension applications of Isham Carter (S39293) and Jim Capers (R1669).

[16]Pension application of Edward Harris (R6469).

[17]Andrew Waters, The Quaker and the Gamecock: Nathaniel Greene, Thomas Sumter, and Revolutionary War for the Soul of the South (Havertown, PA: Casemate, 2019), 69.

[18]Pension applications of Allen Jeffers (S1770) and Berry Jeffers (W10145); Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters, “Pay Roll of Capt. William Smith’s Troop of L. D. in the Regt. Commanded by Lt. Col. John Thomas, Genl. Sumter’s Brigade,” revwarapps.org/b26.pdf.

[19]Pension applications of Daniel Tolar (S42403), William Cockrill (S39349), William Roger (S36276) and James Dobbins (W25534).

2 Comments

Hi Mr Dorney

I have very much enjoyed your articles.

I am interested in the 0.7 percent in your study who claimed service in the NC Continental Line and the SC State Troops. I know that many were from the Mecklenburg Co area, but have evidence of one from Bladen County who first served with William Washington before joining Wade Hampton’s Regiment of State Troops.

Would it be possible to get the names in your study of those men who claimed service in the NC Continental Line and the SC State Troops?

Thanks

Les, I believe the figure you are referencing are SC Continental soldiers and also those who served in the State Troops. Please send me an email:

do******************@gm***.com