In discussions on the American Revolutionary War, the contributions of Texas are seldom brought up.[1] But in the 1770s, Texas, inhabited by Spaniards and Native Americans, was a hub of activity. While the signing of the Declaration of Independence occurred on July 4, 1776 in Philadelphia, Tejanos (Texans) manned outposts, guarded New Spain’s claims, and reconnoitered neighboring Indian tribes.[2]

In the early 1690s, Texas secured a formal place within the Spanish Empire when it became an official province of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. By 1776 Spain had claimed dominion over what was then called New Spain, vast tracts of land in the North American Southwest, Central America, South America, and the West Indies. San Antonio de Bexar was the capital of provincial Texas. Only three civil settlements existed in Texas: the Villa de San Fernando de Bexar, La Bahia, and Villa de Bucareli (later renamed Villa de Nacogdoches in 1779).[3] Altogether, Spanish Texas boasted a population of roughly 3,000 Spanish citizens.

On June 21, 1779, Spain officially declared war on Great Britain, entering the Revolutionary War on the side of France and the emerging United States.[4] When news of Spain’s entry into the war reached New Orleans, Louisiana Governor Bernardo de Galvez cast his gaze on British West Florida.[5] In no time, Galvez assembled an army of 7,000 troops bent on West Florida’s conquest.[6] Among the many obstacles he faced throughout his efforts to procure West Florida for Spain was feeding his troops. In 1779, Galvez sent an emissary, Francisco Garcia, to Texas with a request to purchase 1,500 to 2,000 cattle. When rounding up this livestock, Texas officials made sure to send enough bulls so that the stock could procreate in Louisiana to prevent depletion or scarcity while under Galvez’s command. When the herds were ready to make the trek to Louisiana, armed soldiers escorted rancheros (ranchers), vaqueros (cowboys), and their livestock to Louisiana.[7]

Throughout the process of raising enough cattle to meet Galvez’s demand, Spanish officials encountered numerous obstacles that barred the smooth completion of that end. For starters, by September 20, 1779, Francisco Garcia had returned to New Orleans, even though Texas officials expected him to take charge of the herd. At the same time, concerns regarding the inability of most cattle’s exportation from the El Espiritu Santo mission created a delay in the delivery of sufficient numbers of cattle to Galvez; according to Texas officials, cattle from the El Espiritu Santo mission comprised the major part of the herd that was intended for Louisiana. To counter this, Spanish officials explored alternative avenues to round up livestock, including the dispatch of unbranded cattle to Louisiana to make up the difference.[8] Despite these difficulties, the 2,000 requested cattle were procured and sent to New Orleans.[9] For every head of cattle exported out of Texas, ranchers were charged two reales.[10] Proceeds were paid to the Spanish government who utilized those funds to pay for a military escort for the herds’ safe delivery to Louisiana.[11]

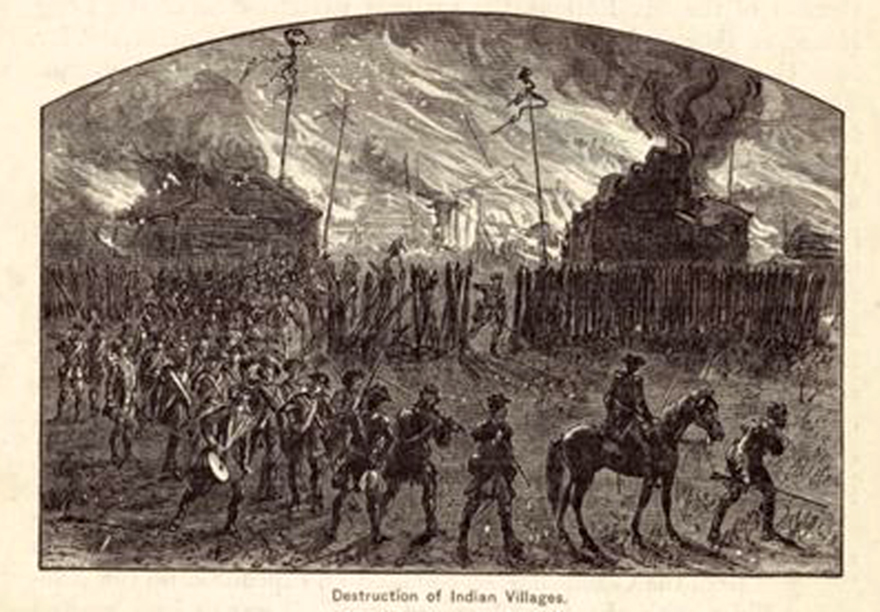

One of the more serious difficulties encountered by Texas officials, and which paused the exportation of cattle to Louisiana, occurred sometime between January and June 1780. During that time a cattle drive was attacked by Comanche Indian raiders, leading to the loss of enough cattle to cause headaches for Spanish officials. These Indian depredations temporarily delayed any further transportation of cattle because no Tejanos wanted, “for any amount of money whatever,” to expose themselves to the dangers of Comanche raids—both to protect their lives and avoid the risk of losing their herds.[12] For much of 1780, Native Americans, notably Comanches and Lipan-Apaches, challenged encroaching Tejanos who, according to Texas governor Domingo Cabello, refused to attend to their herds out of fear of Indian hostility.[13] The threat of Indian reprisals thus contributed to the limited amount of cattle, delays in the arrival of stock, and possible inability of Texas to export and deliver optimal amounts of livestock to Galvez.

Despite tensions with Native Americans, which was nothing new to the Tejanos, Texas cattle continued to arrive in Louisiana until 1782.[14] From 1779 to 1782, Texas delivered roughly 10,000 to 15,000 head to Louisiana for Galvez’s invasion force.[15] Despite Indian raids and delays, the supply of cattle was sufficient, and Spain conquered British West Florida after the Siege of Pensacola.[16] Texas cattle fed the men who achieved that end.

In addition to providing cattle, some Tejanos served in Galvez’s army, but the contributions from Texas did not end there.[17] Finances were raised in Texas to help pay for the war effort and secure North America’s independence from the British Crown.[18] During the entire war, roughly 1,659 pesos were donated to the United States from among the Texas population. These finances helped pay for the sailors and provisions in French Admiral de Grasse’s fleet that was pivotal in effecting the British surrender at Yorktown in 1781.[19]

Largely forgotten and ignored, Texas’s role in the American Revolutionary War contributed to Spain’s victory over Britain in the Gulf Coast. Spain’s conquest of British West Florida threatened British control over its southern colonies. Consequently, in the wake of Spain’s entry into the conflict, Britain was forced to consider channeling resources, attention, and efforts—all of which were stretched thin from fueling the Revolutionary War—away from the original thirteen colonies to protect and maintain Gulf Coast possessions. There is no doubt that the Tejanos, who transported thousands of cattle from Texas to Louisiana between 1779 and 1782, supported Liberty’s cause, helping dislodge the British from West Florida. Additionally, the Tejanos who donated money to the independence movement and served in Galvez’s army aided the North American rebels directly. For these reasons, Tejanos should be commemorated for their contributions to the establishment of the United States of America.

[1]For further reading on Texas and the American Revolution see: Robert S. Weddle and Robert H. Thonhoff, Drama and Conflict: The Texas Saga, 1776 (Austin: Madrona Press, 1976); Robert H. Thonhoff, The Texas Connection With the American Revolution (Burnet, Tex.: Eakin Press, 1981).

[2]Company of San Antonio de Bexar, July 4, 1776, Roster, Bexar Archives, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin, translated by Pablo P. Ruiz, Box 2C25.

[3]Robert H. Thonhoff, The Vital Contribution of Texas in the Winning of the American Revolution: An Essay on a Forgotten Chapter in the Spanish Colonial History of Texas (Karnes City, Texas), 3-4,granaderos.org/july.pdf.

[4]Thomas E. Chavez, Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002), 133.

[5]Louisiana was a Spanish colony in North America following the Seven Years’ War.

[6]David F. Marley, Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present (Denver: ABC-CLIO, 1998), 335. Galvez initially only raised 1,400 troops, but his numbers would eventually swell to over 7,000; Cecil Johnson, British West Florida, 1763-1783 (1942. Reprint, Hamden: Archon Books, 1971) 213.

[7]Teodoro de Croix to Domingo Cabello, August 16, 1779, Bexar Archives, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin, translated by John A. Orange Jr., Box 2C35.

[8]Domingo Cabello to Teodoro de Croix, September 20, 1779, Bexar Archives, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin, translated by John A. Orange Jr., Box 2C36.

[9]Teodoro de Croix to Domingo Cabello, November 24, 1779, Bexar Archives, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin, translated by William C. Taylor, Box 2C37.

[10]Proceedings concerning Marcos Hernandez’ petition to export stock to Louisiana, May 30, 1780, Bexar Archives, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin, translated by John A. Orange Jr., Box 2C40.

[11]Proceedings concerning Marcos Hernandez’ petition to export stock to Louisiana, May 30, 1780; Domingo Cabello to Teodoro de Croix, June 11, 1780, Bexar Archives, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin, translated by John A. Orange Jr., Box 2C41; Teodoro de Croix to Domingo Cabello, September 10, 1780, Bexar Archives, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin, translated by John A. Orange Jr., Box 2C42.

[12]Domingo Cabello to Teodoro de Croix, July 10, 1780, Bexar Archives, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin, translated by John A. Orange Jr., Box 2C41.

[13]Domingo Cabello to Teodoro de Croix, December 20, 1780,Bexar Archives, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin, translated by John A. Orange Jr., Box 2C44.

[14]Translation of proceedings concerning Antonio Blanc’s petition to export cattle to Louisiana, May 4, 1782, Bexar Archives, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin, translated by William C. Taylor, Box 2C47.

[15]Thonhoff, The Vital Contribution of Texas in the Winning of the American Revolution, 5.

[16]N. Orwin. Rush, The Battle of Pensacola: March 9 to May 8, 1781: Spain’s Final Triumph Over Great Britain in the Gulf of Mexico (Tallahassee: The Florida State University, 1966), 31-32.

[17]Thonhoff, The Vital Contribution of Texas in the Winning of the American Revolution, 5.

[18]Chavez, Spain and the Independence of the United States, 213-214.

[19]Thonhoff, The Vital Contribution of Texas in the Winning of the American Revolution, 6-7.

2 Comments

Mr. Kotlik,

I enjoyed your informative article TEXAS AND THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION.

I have authored two books, TEJANO PATRIOTS OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION 1776-1783, edited and annotated by Judge Robert H. Thonhoff, and ROSTERS OF TEJANO PATRIOTS OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION 2776-1783. These books have been used by such organizations as SAR and DAR as references for admission and TEJANO contributions. My ancestors are designated as Patriots in SAR and DAR.

The writing of these books also included my ancestors’ participation in TEJANO history. My ancestors are part of the 1718 Founding Families of San Antonio and the 1731 Canary Islanders.

Jesse O. Villarreal, Sr.

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who fought in the war against the British.

We are making a documentary film y would like your input.

Please call or text me at 361 9604950 after 10:09 am tomorrow at your convenience.

Thank you .