Andrew Pickens is the very image of the hard-nosed Patriot, but after the surrender of Charleston, South Carolina on May 12, 1780, he gave the British good reason to hope he would join them. In order to understand Pickens’ thinking, it is instructive to begin with Andrew Williamson, who did join the British and lived only thirteen miles from Pickens in the Backcountry of western South Carolina. Although born in Scotland and illiterate,[1] Williamson had somehow married into the prominent Tyler family of Virginia and amassed a considerable estate, named White Hall, by selling cattle, hogs and other supplies to Ninety Six and other frontier forts.[2] By the time Charleston surrendered, Williamson was a brigadier general of militia in Ninety Six District. He was about fifty years old, with a wife suffering from a terminal illness.[3]

Williamson learned of the Charleston surrender four days after it occurred.[4] He inquired about the conditions for the surrender of his own troops, and he was offered the same terms granted to militiamen captured at Charleston. They would be “permitted to return to their respective homes as prisoners on parole; which parole, as long as they observe, shall secure them from being molested in their property by the British troops.”[5] Williamson assembled a council of officers at White Hall, had the terms of surrender read to them, and called for a show of hands of those who wished “to press the march, until a number sufficient for offensive operations should be collected, and then to keep up a kind of flying camp, until reinforced from the main army.”[6] Capt. Samuel Hammond was “struck dumb” when all but a few of Williamson’s officers voted to accept the British terms of surrender. “Yet Williamson persevered,” according to Hammond:

Colonel Pickens was not of the council, but encamped a few miles off. The general again addressed the council, expressed his wish for a different determination, and proposed to ride with any number of the officers present, as many as chose to accompany him, to Pickens’ camp; stating that he wished to advise with the colonel, and to address the good citizens under his command.[7]

According to Hammond, “General Williamson had a short consultation with Colonel Pickens–his troops were drawn up in square, all mounted – the general addressed them in spirited terms, stating that with his command alone, he could drive all the British force then in their district before him, without difficulty.” Again Williamson was disappointed when only Capt. James McCall, another captain and a few privates voted to continue the struggle.[8] By June 8 Williamson and most of his troops had given up the fight and gone home.[9] Pickens also took parole and retired to his home in the Long Cane Settlement at present Abbeville.

British Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis, attempted to consolidate his hold on South Carolina with a chain of outposts, one of the most important being at Ninety Six in the Backcountry about twelve miles northeast of White Hall. As Cornwallis noted, “keeping possession of the Back Country is of the utmost importance. Indeed, the success of the war in the Southern District depends totally upon it.”[10] The British had too few men at Ninety Six to both patrol the large area and also defend the fort against attack, so it was essential to win over the local men of influence in hopes they would lead others in suppressing the remaining Whigs. Williamson complied. Soon he was hosting British officers and toasting the King at his White Hall plantation house,[11] selling provisions to the British garrison, and giving intelligence about the troops he had formerly commanded.[12] Williamson would later be reviled as the Benedict Arnold of the South.[13]

The British hoped the forty-year-old Pickens would follow Williamson’s example. He had served as a militia officer under Williamson as early as November 1775, when they fought off Loyalists at Ninety Six. In the summer of 1776 they were again comrades in arms in an expedition against Cherokees and Loyalists. Williamson tried to win Pickens over to the British side,[14] but Pickens was still abiding by his parole in August when Cornwallis wrote,

By what I hear of Pickens I should think him worth getting. However, it may not be safe to enter into any treaty with him without the approbation of General Williamson, to whom I shall always pay the greatest attention and gratify in every thing that would fix him to our interests in the firmest manner.[15]

On September 1, Lt. Col. John Harris Cruger, commandant at Ninety Six, wrote to Cornwallis that “the colonel [Pickens], is favorably reported.”[16] Cruger increased the pressure on Pickens and others to play an active role on the British side:

My plan of proceeding then with the inhabitants on this side the Saluda in 96 District, provided your Lordship has no objections, will be immediately to call them together and tell them that the aid and military exertions of every man in the country is required against the common enemy, and that, if they will readily engage to make use of arms for the defence of the country (this is also Williamson’s idea), that arms shall be given them, and that, if any should refuse, we shall look upon them inimical and not entitled to protection or the common benefits of citizens.[17]

Two weeks later Cruger was alarmed by news that Col. Elijah Clarke had laid siege at Augusta.[18] Clarke had with him about two hundred other Georgia refugees — volunteers who found it safer to be with an armed force than to remain at home. Cruger rushed to Augusta and drove Clarke away on September 18, but Clarke further unnerved him by entering the settlement on Long Cane Creek just twenty miles from Ninety Six. On September 20 Williamson’s secretary, Malcom Brown, gave assurance that “W[illiamson] is gone into the Long Cane settlement and means with Pickens to get the country to rise and asist Crugar in getting at Clark.”[19] Pickens’s aid proved to be unnecessary, as Williamson informed the British commander at Charleston the next day: “When I learnt that Clark and his party were in the Country I went with Colo Purves [John Purvis] & Capt. [Benjamin] Tutt to Colo Pickens’s and sent for others of the principal Inhabitants to meet me there, where I learn’d that only six of the People in that settlement had gone of[f].”[20]

By October the British were even more confident that Pickens would join the British side. British Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour, commandant at Charleston, had sent Pickens a letter that interested Pickens enough that he wanted to go with Cruger and Williamson to meet with Balfour.[21] A letter Cruger wrote to Cornwallis on November 27 gives a clue to the contents of Balfour’s letter: “I think there is more than a possibility of getting a certain person in the Long Cane settlement to accept of a command, and then I should most humbly be of opinion that every man in the country should be obliged to declare and act for His Majesty or quit.”[22] That “certain person” could only have been Pickens, and apparently Balfour had offered him the command of a Loyalist regiment.

Cornwallis replied, “I should be very glad to hear that the person you allude to would take a command, and I then think that this would be a very proper time to insist on the declaration you propose [that every man in the country should be obliged to declare and act for His Majesty or quit]. Without it there can be no hopes of the settlement remaining long at peace.”[23] On December 5 Cruger, Williamson and Pickens still had not been able to leave Ninety Six to confer with Balfour, but Cruger wrote to Cornwallis, “when we get to town, we will with Colonel Balfour, if your Lordship approves, settle the business there both for the command and the declaration.”[24] From this letter there can be little doubt that Pickens at least gave the impression that he was considering taking the command of a Tory regiment.

On the evening of December 4 Col. Elijah Clarke and others returned to the Long Cane Settlement, triggering an event that changed whatever intentions Pickens had. That event was the skirmish of Long Cane on December 12. Although it was certainly not a turning point in the war, we believe it was a turning point for Pickens. The outcome of the skirmish was certainly of considerable significance to the garrison at Ninety Six, and we believe it merits more attention. Cruger described how the skirmish came about in a letter to Cornwallis dated December 15:

Last Tuesday week [December 5] I heard of a party of rebels under Clark, Few, Twigs, Candler etc crossing the Saluda into Long Cane settlement. They reported themselves 4 to 500. One of their objects was to get the inhabitants to join them, for which purpose they order’d Williamson, Pickens and the principal people of the country who were on parole to attend them, alledging that we had violated the capitulation. They used both soothing and threatening arguments to those gentlemen, who, I have the pleasure to inform your Lordship, behaved like men of honor and persisted in a different opinion.[25]

“Clark” was of course Col. Elijah Clarke, who commanded one party of volunteer refugees from Georgia, including Maj. William Candler. Col. Benjamin Few commanded another group of Georgia volunteers, and because his commission predated that of the other colonels, he was nominally in overall command.[26] Also present but not mentioned by Cruger was Maj. James McCall, who commanded volunteers from South Carolina. “Twigs” was Col John Twiggs of Georgia. There may actually have been more than 400 of the Americans; American Maj. Samuel Hammond said there were more than 500, but a British source gave the number as only 300.[27]

Hammond described the incursion and the detention of Williamson and Pickens in more detail:

It was resolved, in council, to make a bold and rapid push through the western part of Ninety-Six District, into the Long Cane settlement, west of the British, stationed at the town, Cambridge, or Ninety-Six. Our wish also, was to draw out the well-affected of that part of the country, who had been paroled by the enemy on the surrender of General Williamson. Believing that the british had violated their faith under this capitulation, having compelled the whigs to bear arms against their late companions in arms, instead of leaving them at home until exchanged as prisoners of war, this would be a favorable opportunity for them to join us. . . . the council of officers detached Major McCall, with his command, to see Colonel Pickens, and invite him to co-operate with us, as the British, by their breach of faith, had freed him from the obligations of his parole. Major McCall was selected for this purpose, not only for his known prudence and fitness, but for his personal friendship with Colonel Pickens. Major S. Hammond, with his command, was ordered down to Whitehall, the residence of General A. Williamson, for the same purpose and views. Captain Moses Liddle was united with him in this mission. Both detachments were ordered to bring the gentlemen sent for, to camp, whether willing or otherwise. They were both, of course, taken to camp. The object of the whigs was to gain their influence and their better experience to our cause. They both obeyed the call promptly, but declared that they did not go voluntarily, and considered themselves in honor bound by their parole, whether the British violated their faith or not, so long as it was not violated by them.[28]

While Williamson and Pickens were being detained,[29] Cruger assembled a force to attack the Americans:

Last Monday morning [December 11] was the soonest I could get together any militia, when Brigadier General Cunningham brought over with him about 160 – Kirkland’s and King’s regiments furnished about 110 – to which I added 150 rank and file of this garison with one field piece under Colonel Allen and sent them off on Monday night at 11 o’clock in hopes of surprizing the enemy, who we had reason to believe lay at General Williamson’s, but unluckily found no body there, but received intelligence that they were encampt six miles farther on, for which the march was immediately continued, but here again we fell short by about three miles. A halt was then made, the day being far spent.[30]

Gen. Robert Cunningham had recently been given command of the loyalist militia of Ninety Six District. Colonels Moses Kirkland and Richard King commanded militia regiments from the Long Cane Settlement. Col. Isaac Allen, in overall command, had provincial troops — Americans trained and equipped like British regulars — from the 1st Battalion of De Lancey’s Brigade and/or the 3rd Battalion of New Jersey Volunteers. The presence of a field piece — probably a three-pounder capable of firing a three-pound cannon ball — suggests that Allen expected the Americans to be in Williamson’s plantation house.

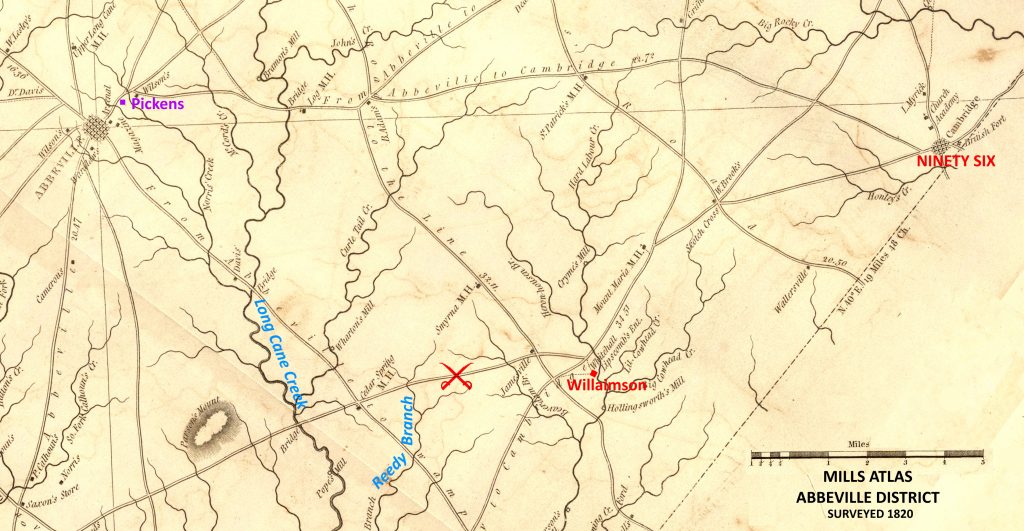

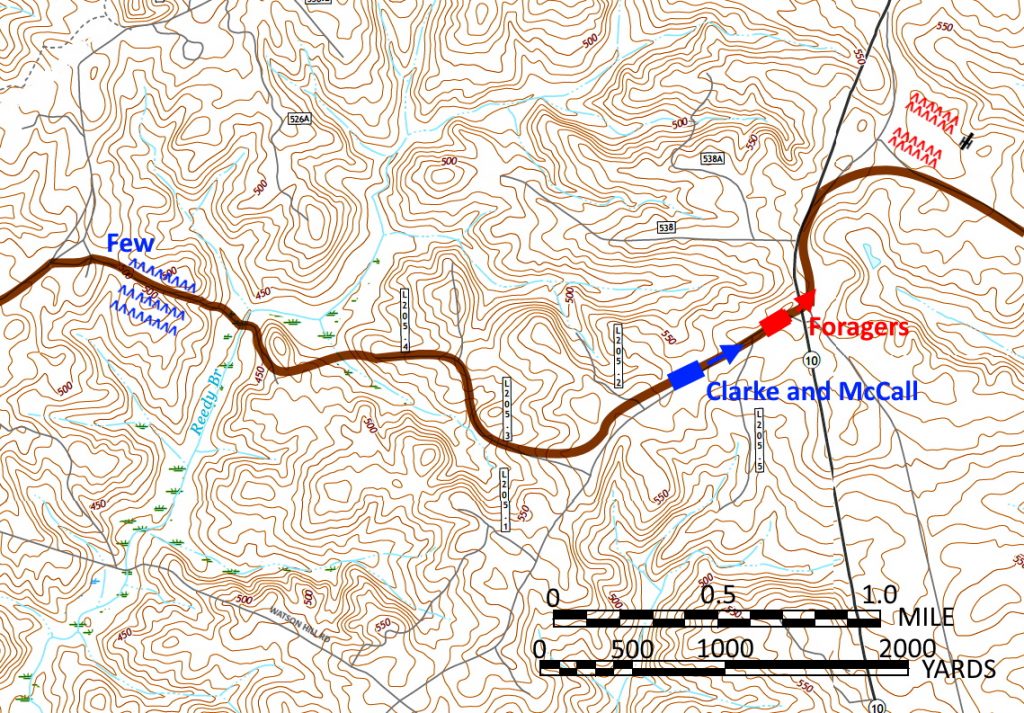

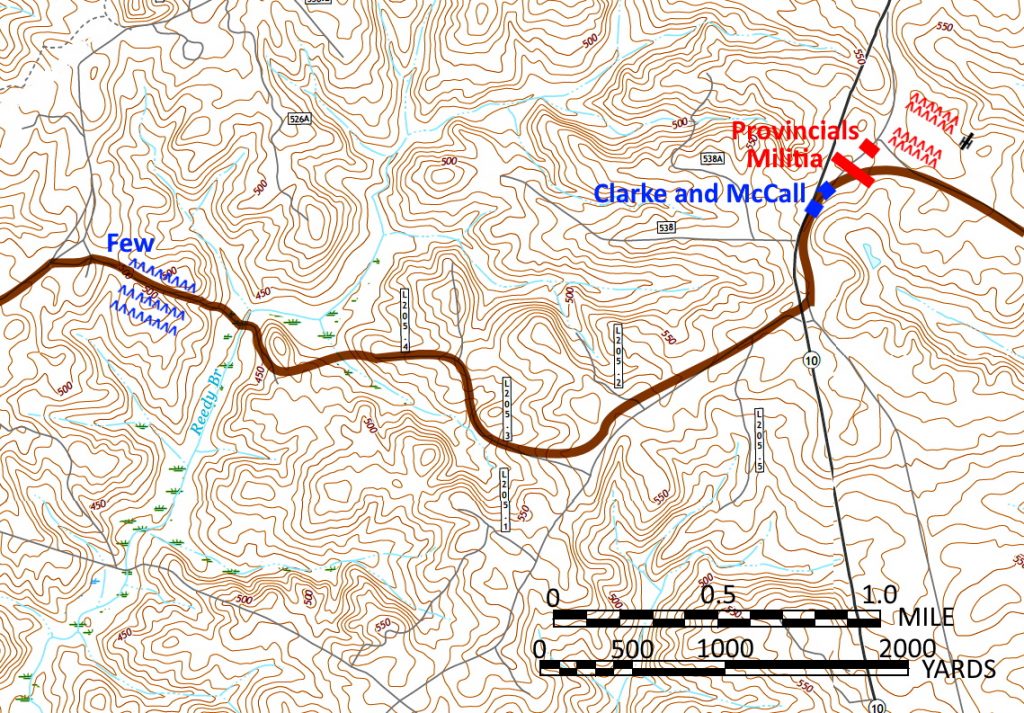

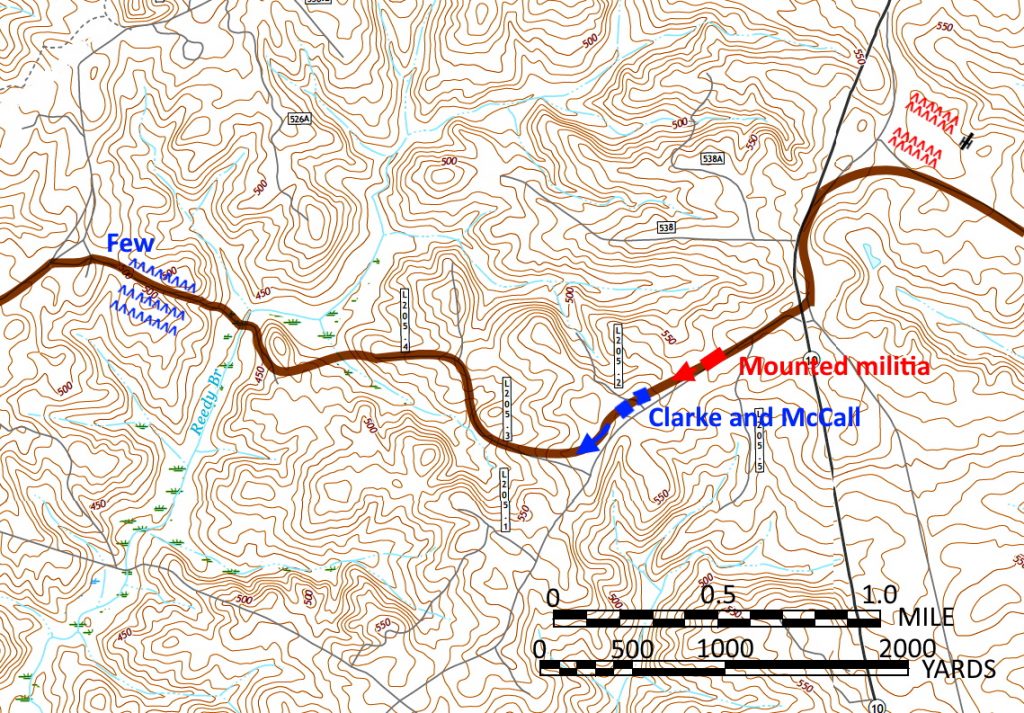

One of the controversial aspects of the Long Cane skirmish is its location. A roadside marker gives a location about two and a half miles northwest of Troy and ten miles southwest of Williamson’s house. A different location about where Cedar Springs Road crosses Reedy Branch five and a half miles southwest of White Hall was given by James Evans, who was said to have been a soldier at the skirmish.[31] At least two other sites have been proposed — one about three miles west of the location indicated by the historical marker, and another about seven miles southwest of White Hall. We propose a site based on Cruger’s account and five pension applications stating that the skirmish happened near Reedy Branch.[32] According to Cruger, the Americans camped six miles (probably measured along the roads) from White Hall, and the British camped three miles short of that distance. Because the Americans were traveling with baggage wagons, they would have been on a road probably significant enough to appear on Mills Atlas. From this information we conclude that the running skirmish occurred about where we show the crossed-swords symbol in the map above. In the maps below we depict the camps and skirmish in approximately this location on roads now in Sumter National Forest.

Failing to find the Americans at White Hall, the British pushed on under a full moon until early on December 12. The skirmish began that afternoon after the Americans discovered the enemy camp three miles away. Believing it to include only a small number of Loyalist militiamen, Clarke called for volunteers to attack them. In the words of soldier James Lochridge, “news came in that 150 or 200 Tories, were in the immediate neighborhood. Gen’l. Clark call’d for 100 Volunteers – to join him in the Sport of whipping them or taking them prisoners.”[33] First contact was with a Loyalist foraging party.[34] The most detailed account of the fighting is by Hugh McCall, who probably heard it from his father, Col. James McCall:

The enemy were within three miles of Few’s camp before he was apprised of their approach. Colonel Clark, Lieutenant Colonel McCall, and Major Lindsey [John Lindsay], with 100 Georgia and Carolina militia, were ordered to meet the enemy, commence the action, and sustain it until the main body could be brought up to their assistance. They advanced about one mile and a half and engaged the enemy’s front, which was composed of royal militia. The action was lively for a short time, and Clark sent an express to Few to hasten the march of the main body. In about 10 minutes the loyalists retreated, some of them fled, and the remainder formed in the rear of the regular [provincial] troops.[35]

As the Americans pursued the fleeing Loyalist militiamen into their camp, they “found to our great astonishment, & when it was too late to retreat with safety, that there were ab’t. 500 Tories & 150 or 200 British. We were compelled to fight, or surrender.”[36] A letter written by an unknown participant gave the following account from the British perspective:

About sun-set [5pm local solar time] they made their appearance, came within 100 yards, dismounted, tied their horses to a fence, and came on in a rapid manner. It not being expected that they would be so quick in attacking, the regular troops were but just then formed, and were so posted as not to be observed by the rebels till they got over a small rising ground; being then within 40 yards, they found their mistake in thinking they had nothing but militia to contend with. A sudden halt was made, and a fire given to us, which wounded only three of our men.[37]

Hugh McCall’s account continues as follows:

Colonel Allen ordered the loyalists to commence and sustain the attack, until the regular troops were formed: when this was effected, the bayonet was presented and the loyalists were ordered to form in the rear and turn upon the American flanks. About this time, M’Call was wounded in the arm, and his horse killed, and he was so entangled by the horse falling upon him, that he narrowly escaped. The Americans retreated and were charged by the enemies dragoons. Major Lindsey had fallen under three wounds, and was left on the ground; in that condition, Captain Lang, of dragoons, fell upon him while he lay on the ground, chopped his hands and arms in several places, and cut off one of his hands.[38]

According to Cruger:

[The British] gave one fire and rush’d on with their bayonets. A rout ensued and soon became general. Our militia avail’d themselves of this circumstance and pursued for two miles with spirit. The soldiers follow’d those of the enemy who had not time to get on their horses. the first rebel that arrived in their camp sett the rest agoing, and in an instant they were all off, leaving six waggons and 30 head of cattle, and on Wednesday morning [December 13] recross’d the Saluda. Their loss, kill’d, is reported from 30 to 50. Prisoners taken: one major badly wounded and 8 privates chiefly wounded. The Colonels Clark and McCall are wounded but escaped. Our loss: 2 militia men kill’d, 6 wounded, and 3 soldiers wounded.[39]

According to pension applicant Vachel Davis (R2770), “After this defeat, the troops under Clark were about 300 strong, starving and almost naked were ordered to disperse through the Country and do the best they could in procuring provissions and clothing.”[40] Among the American losses was John Wallace, who “was wounded & taken prisoner taken to the post of 96 I Lay in close confinem’t Ironed to the floor of my Dungeon for three months.”[41]

Hugh McCall wrote that after the skirmish Tories plundered Pickens’ plantation and abused his family.[42] The failure of the British to protect his family and property may have been what decided Pickens to offer his services to the Americans. Together with Capt. Andrew Hamilton, he went in search of Col. Few. Instead they fell into the hands of Tories, as related by Capt. Hamilton:

Pickens & himself went unaccompanied by others to confer with a Col Few from Georgia who then had a few troops in the district of Ninety Six, all true Whigs, that when Col Pickens & himself (the deponent) were on their road to see Col Few, a female of the tory stamp directed them to a Camp of British soldiers & Torys by whom Pickens & himself were made prisoners & sent to the Village of Cambridge or Ninety six, where they remained prisoners one month, under a British Officer by the name of Allen, by some means Col Pickens obtained his, & my release, from imprisonment, while prisoners we were treated with great attention & kindness by the British attributable I believe to the popularity & influence of Gen’l Pickens.[43]

The detention of Pickens at Ninety Six must have begun after December 17, after Cruger had gone to Charleston and left Allen in command. Allen’s forced attention and kindness to Pickens did not work, and on December 29 he wrote to Lt. Henry Haldane,

Colonel Pickens, who you saw here, has gone to the rebels. He is said to be a good soldier and may give us some trouble in this quarter … General Williamson is at home, much distressed with the perfidious behaviour of his friend Pickins. I hope we will now have done with protection and paroles.[44]

To Cornwallis Allen wrote,

I have received certain information that Colonel Pickins . . . with about one hundred men have left the Long Cane settlement and joined the enemy. These are all men of influence with the rebels and will be such an accession of strength to those who had left the country before . . . as will make them much too powerfull for our militia, which will render our supplies at this post very precarious.[45]

Pickens joined Gen. Daniel Morgan and helped him secure the decisive victory at Cowpens on January 17,1781. On the day before, Cornwallis had ordered all of Pickens’s remaining property seized or destroyed, and Pickens “if ever taken, instantly hanged.”[46]

Pickens could easily have chosen to accept a commission as a Loyalist general, or he could have retired like Williamson in safety and comfort near Charleston. He understood that breaking parole and taking up arms with the Americans was a hanging offense, and he was deciding not only for himself, but for those who would join him. His choosing to join the Patriot cause is all the more honorable considering how tempted he was to make a different choice.

[1]Hamilton Brown pension application W1707, William Clark W8610, Hezekiah Davis S32211, Edward Doyle S32216, Joseph Lee R6252. These and other pension applications are transcribed mainly by Will Graves at revwarapps.org.

[2]Llewellyn M. Toulmin, “Backcountry Warrior: Brig. Gen. Andrew Williamson: The ‘Benedict Arnold of South Carolina’ and America’s First Major Double Agent—Part I,” Journal of Backcountry Studies 7, no. 1 (Spring 2012), 1-46.

[3]Malcom Brown to Maj. John Bowie, October 28, 1780, “The Bowie Papers, Part 2, 1778-1780, Bulletin of the New York Public Library, vol. 4 (January to December 1900), 126.

[4]Samuel Hammond pension application S21807.

[5]Andrew Williamson, “To the officer commanding the British troops on the north side of Saluday River,” June 5, 1780, in The Cornwallis Papers(hereafter CP), ed. Ian Saberton, (Uckfield, East Sussex, England: Naval & Military Press, 2010), 1:115. William R. Reynolds, Jr., “The Parole of Col. Andrew Pickens,” Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution, 10, no. 1.0 (spring 2014), 2. Unknown to Williamson at the time, on June 3 Gen. Henry Clinton had issued a proclamation rescinding pardons except for those “who, convinced of their errors, are firmly resolved … to support … [the] government.”

[6] “General Samuel Hammond’s Notes,” in Joseph Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences (Charleston: Walker & James, 1851), 149-152. Samuel Hammond pension application S21807.

[8]“Hammond’s Notes.” James McCleskey pension application S16475.

[9]Alexander Innes to Cornwallis, June 8, 1780, CP1:112.

[10]Cornwallis to Lt. Col. John Harris Cruger, August 5, 1780, CP1:256.

[11]Alexander Bowie, son of John Bowie, December 22, 1856, letter transcribed by Will Graves,

[12]Maj. Patrick Ferguson to Cornwallis, June 22, 1780, CP1:286. Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour to Cornwallis, June 24, 1780, CP1:239-240. Cornwallis to Balfour, July 13, 1780, CP1:247. Cornwallis to Cruger, August 5, 1780, CP1:256. Cruger to Cornwallis, August 23, 1780, CP2:171. genealogytrails.com/scar/anderson/pickens_andrew_letter.htm. Three American soldiers charged that Williamson had also behaved as a traitor even earlier at Seneca in 1776: John Edmonson pension application S32229, John McCutchen S32406, James Sherer W4512.

[13]Williamson actually became a double agent, providing intelligence to the Americans. Conner Runyan, “The Monument that Never Was,” Journal of the American Revolution(September 2, 2015)

allthingsliberty.com/2015/09/the-monument-that-never-was/. Llewellyn M. Toulmin, “Brigadier General Andrew Williamson and White Hall: Part II,” Journal of Backcountry Studies 7, no. 2 (Fall 2012), 58-98.

[14]Balfour to Cornwallis, June 24, 1780, CP1:240.

[15]Cornwallis to Cruger, August 27, 1780,CP2:172.

[16]Cruger to Cornwallis, September 1, 1780, CP2:175.

[17]Cruger to Cornwallis, September 7, 1780, CP2:182-183.

[18]Clarke signed his last name without the e, but we use the usual spelling.

[19]Balfour to Cornwallis, September 20, 1780, CP2:91.

[20]Williamson to Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour, September 21, 1780, CP2:104-105. Clarke’s Georgia refugees had withdrawn to join Gen. Thomas Sumter and were in the engagements at Fishdam Ford on November 9, 1780, and Blackstock’s Plantation on November 20, 1780.

[21]Cruger to Balfour, October 22, 1780, CP2:136; Balfour to Cornwallis, November 5, 1780, CP3:65; Cruger to Cornwallis, November 14, 1780, CP3:270.

[22]Cruger to Cornwallis, November 27, 1780, CP3:275.

[23]Cornwallis to Cruger, November 30, 1780, CP3:277.

[24]Cruger to Cornwallis, December 5, 1780, CP3:280.

[25]Cruger to Cornwallis, December 15, 1780, CP3:282-283.

[26]Samuel Hammond, “Expedition to Long Canes, and a Mission to Williamson and Pickens” in Traditions and Reminiscences, Joseph Johnson (Charleston: Walker & James, 1851), 530-532.

[27]Hammond, “Expedition to Long Canes.” “Extract of a letter from Ninety-six, Dec. 15, 1780,” Ruddiman’s Weekly Mercury(Edinburgh, Scotland), February 28, 1781.

[28]Hammond, “Expedition to Long Canes.”

[29]James Lochridge (Lockridge) pension application W472.

[30]Cruger to Cornwallis, December 15, 1780.

[31]Samuel Robinson Evans, “Evans History,” members.aol.com/levans3352/public/srevans.html.

[32]James McCleskey pension application S16475, William Thompson R10560, Demsay Tinor S1599, Thomas Townsend W3889, John Wallace S17178.

[33]James Lochridge (Lockridge) pension application W472.

[34]Cruger to Cornwallis, December 15, 1780, CP3:283.

[35]Hugh McCall, The History of Georgia (Atlanta: A. B. Caldwell, 1909), 501-503.

[36]James Lochridge (Lockridge) pension application W472.

[37]“Extract of a letter from Ninety-six, Dec. 15, 1780.”

[38]McCall, History of Georgia.

[39]Cruger to Cornwallis, December 15, 1780.

[40]Vachel Davis pension application R2770.

[41]John Wallace pension application S17178.

[42]McCall, History of Georgia, 503-505. McCall blamed the plundering on Maj. James Dunlap, but Dunlap was in Charleston during this period and had not yet organized and equipped his troops.

[43]Andrew Hamilton pension application S18000. The date of Cruger’s departure is according to CP3:7.

[44]Allen to Lt. Henry Haldane, January 29, 1781, CP3:287-288. Haldane arrived at Ninety Six on December 6 and left before December 22 (CP3:281 and 285). Pickens and Hamilton were apparently Allen’s prisoners for less than two weeks rather than a month as stated by Hamilton.

[45]Allen to Cornwallis, December 29, 1780, CP3:288-289.

[46]Cornwallis to Cruger or Allen, January 16, 1781, CP3:292.

Recent Articles

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Those Deceitful Sages: Pope Pius VI, Rome, and the American Revolution

Trojan Horse on the Water: The 1782 Attack on Beaufort, North Carolina

Recent Comments

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Thank you Eric! I should say that I have enjoyed your work...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...