Many North Carolina soldiers served in both the North Carolina militia/state troops and one of the state’s Continental regiments. To complement my study of the demographics of the militia and state troops, this article presents a detailed look at North Carolina Continental soldiers who served only in the North Carolina Continental Line.

The North Carolina Continental Line came into official existence on November 28, 1775 when the two existing state regiments were “raised to the Continental Establishment.”[1] By early 1776, four additional regiments were raised.[2] Later in the year three more were added, bringing the total to nine regiments. “Despite the need to fill those regiments already established,” the North Carolina General Assembly created another in the spring of 1777.[3] The 10th Regiment barely lasted a year and was permanently disbanded in June 1778.[4] Earlier in that same year so many men had died, deserted, been wounded, and were unfit for service that the nine regiments were consolidated into three.[5] Later in 1778, two short-lived “field” regiments, the 4th and 5th, were raised of “nine months men” to serve in South Carolina and Georgia.[6] The previous three regiments were sent to South Carolina in late 1779 and were present at the siege and surrender of Charleston in 1780. North Carolina Continental regiments were only re-formed after British troops left the state in April 1781.

Between 30,000 and 36,000 North Carolina men served the state during the war with approximately 8,800 of these serving in the North Carolina Line.[7] The latter number may seem high, but North Carolina contributed less than its complement of Continentals to the revolutionary cause. The two main reasons for this were the state’s relative poverty and a heavy reliance on militia and state troops. Additionally, due to the state’s inability to pay sufficient recruitment bounties, officers from neighboring states often came to the North Carolina backcountry during the war and were successful enlisting men for their own state’s lines.[8]

The North Carolina Line was truly “continental” in that it participated in thirty-seven battles and skirmishes across seven states. These men fought only seven battles inside the borders of their home state and never in large numbers.[9] Ironically, during British Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis’s 1780 and 1781 invasions of the state, the North Carolina Line had essentially ceased to exist as almost all of the men still in service (and not on leave) were captured at Charleston in May 1780.

PENSION APPLICATIONS

There are notable differences between the pension applications of Continental soldiers filed under the 1818 and 1828 Pension Acts and those of the militia/ state troops which came after the Pension Act of 1832. Generally, Continental pension applications filed under the 1818 and 1828 Acts are shorter and yield less demographic information than those of the militia/state troops. Under the 1818 Act, the applicant needed to prove nine months service or service until the end of the war in a Continental regiment in addition to being indigent or disabled. Under the 1828 Act, the applicant only needed to establish service in the Continental Line until the end of the war. The 1832 Act opened up pensions to all men who served six months or more regardless of whether they were in the militia, state troops, or Continental Line. Applicants from 1832 onward were generally required to answer a series of prescribed questions that began with the applicants’ place and date of birth, their place and method of enlistment (volunteer, draft, or substitute), officers under which they served, discharge information, and the names of people who could verify their service. In only two demographic areas do Continental applications provide more information: on occupations and property. Another aspect differentiating these Continental applications are the descriptions of the applicants’ many ailments, infirmities, wounds, and impoverishment. One example of the hardships afflicting these pensioners is of a Wilkes County man who had a rupture in his belly and was forced to wear an “iron truss” around his torso. His wife was afflicted with “continual menstrual evacuations” and the couple were caring for a grandchild who had been badly burned as a baby.[10]

Over 3,500 pension applications were reviewed for this work. Of those, 899 were identified as North Carolina Continentals who provided demographic information about themselves and information about their military service. These demographic details were compiled in a simple spreadsheet. Supplementing this pension application data is demographic information compiled from the available “size rolls” of North Carolina Continentals taken at the soldiers’ time of enlistment.

This was not intended to be a definitive study of all North Carolina Continental soldiers. Nor is this work intending to capture information from all of the known North Carolina Continental pension applicants. The data herein represents a small portion (about 10 percent) of the total number of men who served in the North Carolina Line who filed pensions. The analysis, findings, and figures presented here only apply to the data collected from the 899 pension applicants and should not be construed to apply to the entire body of men who served.

A word of further caution is necessary regarding data on dates of birth, length of service, and property/land ownership. Pension applicants were likely to be younger because many older soldiers died before their applications could be filed. As the average lifespan in eighteenth-century America was between forty-one and forty-seven years of age, it certainly seems possible, if not probable, that the men studied here represent the younger range of North Carolina Continental soldiers. Regarding the length of a man’s service, some reported only their fixed term of enlistment while others noted the actual number of months they served. Given these disparities there is some uncertainty on the accuracy of the mens’ overall time in service. Lastly, based on the descriptions of the mens’ property and the need-based requirements of the 1820 Pension Act it appears that many of these men (at least at the time of their applications) were at the lower economic strata of American society based on their owning very little if any personal property and/or land.

PLACES AND DATES OF BIRTH

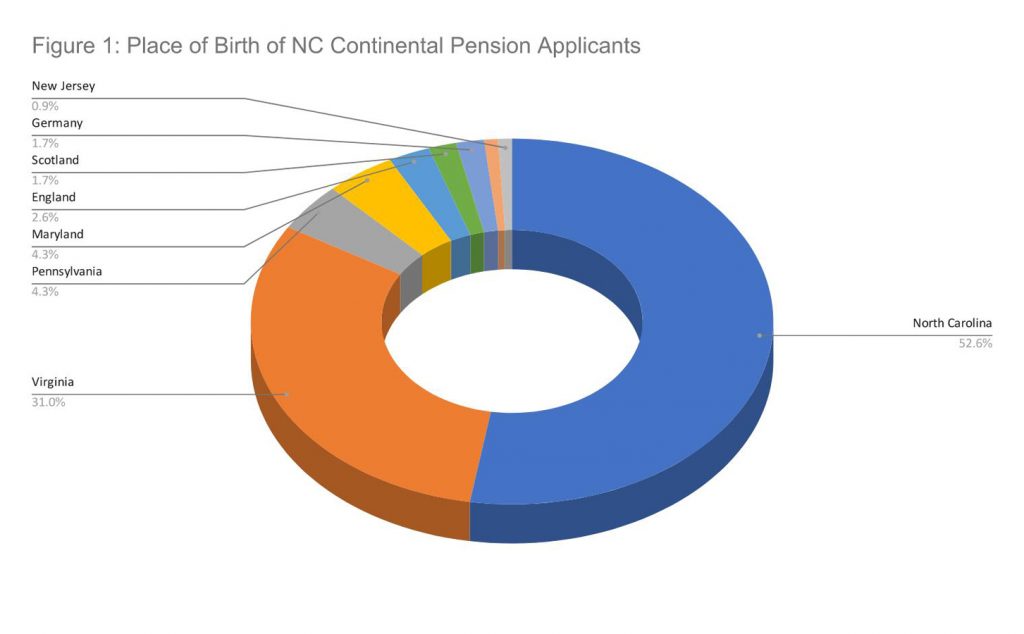

Only thirteen percent of North Carolina Continental pension applicants provided their place of birth. A narrow majority of the men (fifty-two percent) that filed pension applications for Continental service from North Carolina were born in the former colony.[11] Of the almost forty-eight percent of men born outside the state, Virginia accounts for the majority at over thirty-one percent of all men. Pennsylvania and Maryland account for a far lower total of out of state births at four percent each. Only two other states were indicated by the pensioners, New Jersey and Delaware, at less than one percent for each state. Just over six percent of North Carolina Continental applicants were foreign-born from only three countries. England accounts for just under three percent of applicants, Germany and Scotland account for less than two percent each (Figure 1).

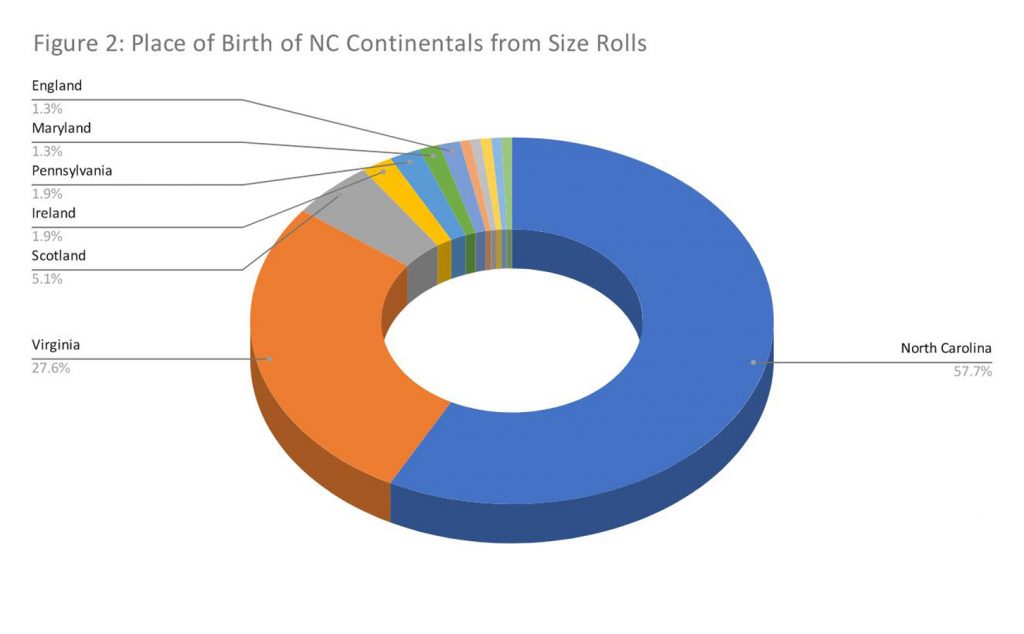

Places of birth indicated in the available North Carolina Continental size rolls mostly align with the data from pension applications. Over fifty-seven percent of the men were born in North Carolina. Similarly, Virginia is the largest contributor of out-of-state births at twenty-seven percent. Pennsylvania and Maryland account for three percent of the total. Eight percent of the men were foreign-born from three countries. Scotland accounts for most of these at just over five percent. Ireland and England account for just over one percent each (Figure 2).

Places of birth indicated in the available North Carolina Continental size rolls mostly align with the data from pension applications. Over fifty-seven percent of the men were born in North Carolina. Similarly, Virginia is the largest contributor of out-of-state births at twenty-seven percent. Pennsylvania and Maryland account for three percent of the total. Eight percent of the men were foreign-born from three countries. Scotland accounts for most of these at just over five percent. Ireland and England account for just over one percent each (Figure 2).

Comparing the place of birth data to that of the militia/state troops yields similarities and differences. The fifty-two percent of Continentals born in the state contrasts from militia applicants of whom forty-three percent were born in North Carolina. About three percent of the militia/state troop applicants were foreign born which is half the percentage noted among Continental pension applicants. Most foreign-born militia pension applicants were from Ireland. In contrast, among the small number of North Carolina Continental pension applicants, none noted their place of birth in Ireland. Only three men from the Continental size rolls indicated an Irish place of birth.

Comparing the place of birth data to that of the militia/state troops yields similarities and differences. The fifty-two percent of Continentals born in the state contrasts from militia applicants of whom forty-three percent were born in North Carolina. About three percent of the militia/state troop applicants were foreign born which is half the percentage noted among Continental pension applicants. Most foreign-born militia pension applicants were from Ireland. In contrast, among the small number of North Carolina Continental pension applicants, none noted their place of birth in Ireland. Only three men from the Continental size rolls indicated an Irish place of birth.

Fortunately, seventy percent of Continental applicants provided their date of birth. The average birth year for these men is 1756. This is one full year earlier than the average birth year of militia/state troops. Interestingly, the average birth date from size rolls (recorded at the time of a man’s enlistment) is earlier still at 1755.

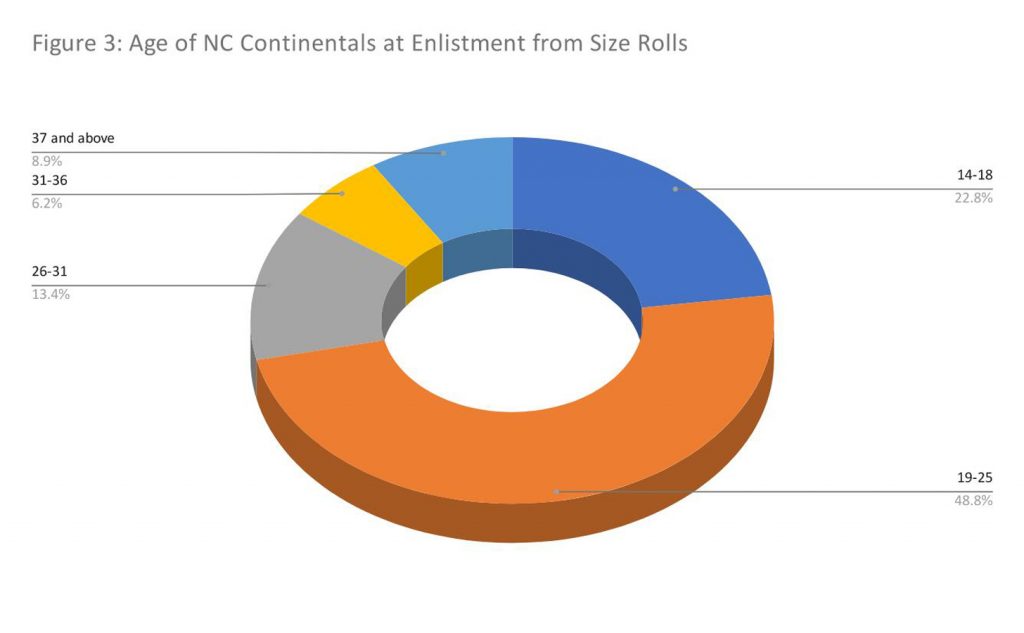

The earliest birth date among the Continental applicants is 1726, the latest being 1767. Compiled size roll data of 401 men reveals an average age of twenty-four years old at their time of enlistment. Compiled data of the soldiers’ ages reveals a fairly wide distribution: enlistees who were both very young and comparably old, a range of fourteen to fifty-four years old. Nearly half of the enlistees were between nineteen and twenty-five years old. Almost twenty-three percent were eighteen years old or younger. Over fifteen percent were thirty-one years old or older (Figure 3).

LENGTH OF SERVICE

Over three quarters of North Carolina Continental pension applicants provided their length of service and number of enlistments. The vast majority of men (eighty-eight percent) served only one term. Almost eleven percent re-enlisted for an additional second term at some point in the war. Only eight men total report enlisting for a third term.

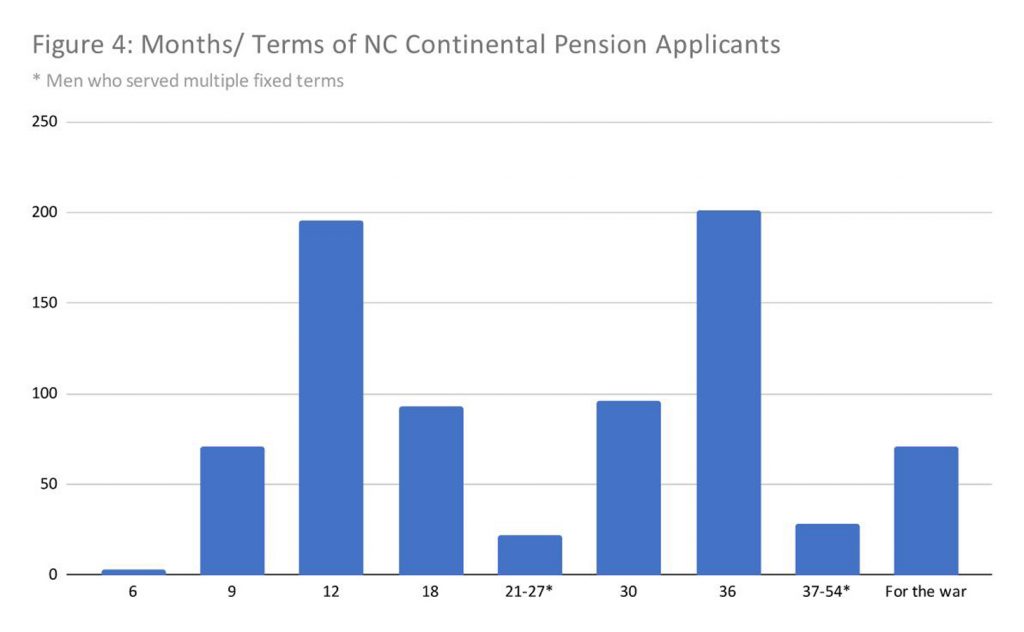

There are many differences in how pension applicants described the amount of time they spent in military service. Some men reported only their fixed term, others indicated the total number of months served, and a few reported both. Among the men who provided their duration of service, the average time served in the North Carolina Line was just over twenty-three months. This figure is somewhat deceiving since no North Carolina Continental pension applicant reported serving that amount of time. Most Continental soldiers served for a fixed term unless they enlisted for the entire war. The most prevalent fixed term of service was for thirty-six months, accounting for over twenty-seven percent of all applicants.[12] A term of twelve months service follows closely behind at twenty-six percent of men. At much lower percentages are men who served eighteen, thirty, and nine month terms in that order each with a range between twelve and nine percent of the total. Just under six percent of men noted they joined “for the war”.

For those that served multiple terms, two distinct patterns emerge. The first is of men who served thirty or thirty-six month terms early in the war then re-enlisted for another twelve month or eighteen month term, these men serving between forty-two or fifty-four months total. The second pattern of service are the men who served a nine month term in the 1778-1779 timeframe then were either drafted or enlisted again for another twelve or eighteen month term in 1781 and 1782, which resulted in combined service of twenty-one to twenty-seven total months (Figure 4).

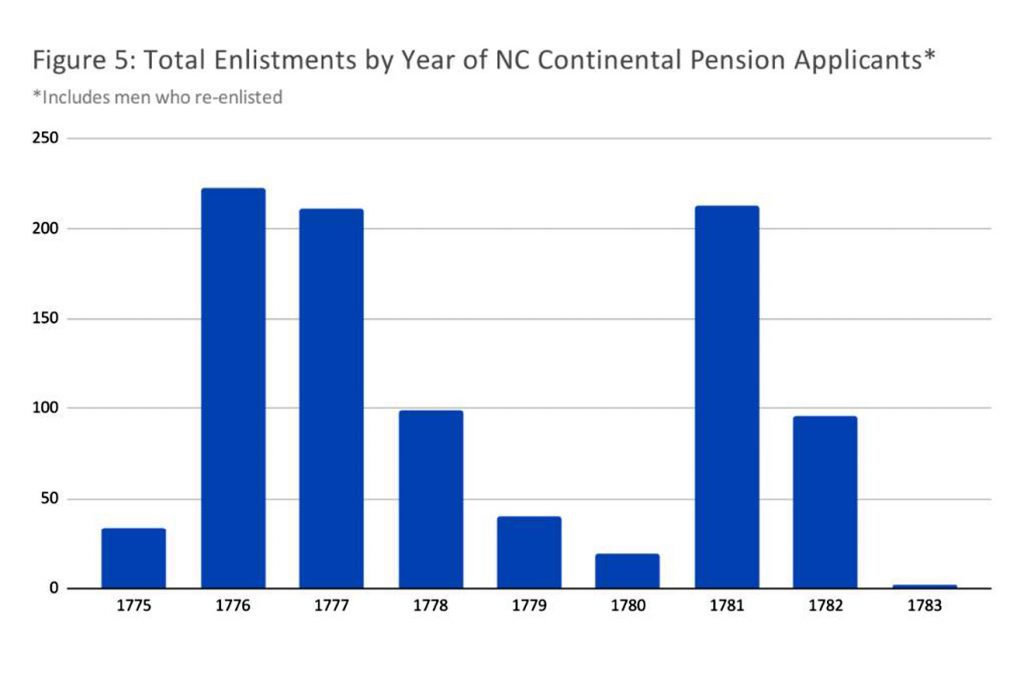

Three broad patterns exist among the pension applicants’ year of enlistment. Over forty-six percent of all enlistments were in the years 1776 and 1777. Virtually all of the men entering service during these two years reported enlistment terms of thirty or thirty-six months. With few exceptions, these men were sent to the northern theater and took part in battles at Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, and Stony Point. Many of these men, if their enlistments had not run out or if they had re-enlisted, were present at the siege of Charleston. The second pattern is of the approximately fifteen percent of men who enlisted in 1778 and 1779 for nine months. These “nine months men” appear, for the most part, to have largely been drafted from the militia and mostly remained in the South, taking part in the Battles of Brier Creek and Stono Ferry in 1779. The third pattern comprises the over forty percent of applicants who served twelve or eighteen month terms spanning the period after the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in March 1781 to the end of 1782. Nearly a third of these men saw action at the Battle of Eutaw Springs (Figure 5).

Three broad patterns exist among the pension applicants’ year of enlistment. Over forty-six percent of all enlistments were in the years 1776 and 1777. Virtually all of the men entering service during these two years reported enlistment terms of thirty or thirty-six months. With few exceptions, these men were sent to the northern theater and took part in battles at Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, and Stony Point. Many of these men, if their enlistments had not run out or if they had re-enlisted, were present at the siege of Charleston. The second pattern is of the approximately fifteen percent of men who enlisted in 1778 and 1779 for nine months. These “nine months men” appear, for the most part, to have largely been drafted from the militia and mostly remained in the South, taking part in the Battles of Brier Creek and Stono Ferry in 1779. The third pattern comprises the over forty percent of applicants who served twelve or eighteen month terms spanning the period after the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in March 1781 to the end of 1782. Nearly a third of these men saw action at the Battle of Eutaw Springs (Figure 5).

Comparatively, North Carolina Continental applicants served over twice the amount of time as their militia state troop counterparts (twenty-three months compared to about ten months total). These same Continentals, however, served half as many terms as the “average” militiaman. Over ninety percent of militia applicants served two or more terms compared to eighty-eight percent of Continentals who served one term.

Comparatively, North Carolina Continental applicants served over twice the amount of time as their militia state troop counterparts (twenty-three months compared to about ten months total). These same Continentals, however, served half as many terms as the “average” militiaman. Over ninety percent of militia applicants served two or more terms compared to eighty-eight percent of Continentals who served one term.

BATTLES

About seventy-five percent of pension applicants who served in the North Carolina Line saw action in a battle or skirmish. This percentage is slightly more than their militia and state troop counterparts of whom sixty-eight percent participated in a battle or skirmish. Continentals who reported only one battle are the most prevalent at thirty-one percent of men. Men who were in two and three battles were nineteen and fourteen percent of the total number of men, respectively (Figure 6). Comparatively, the number of battles for these Continentals generally align with the North Carolina militia and state troops.

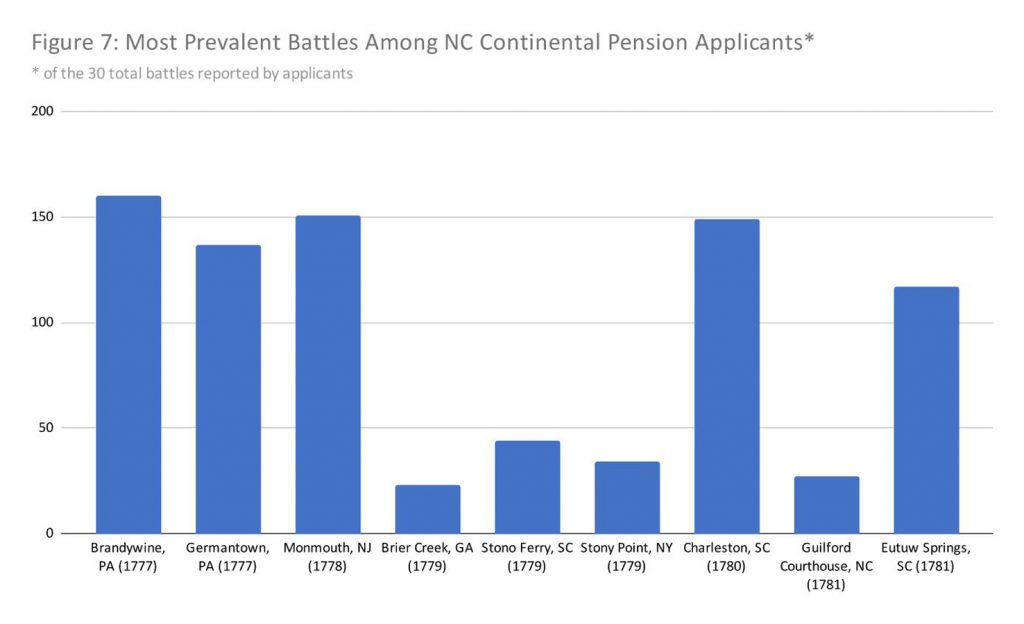

Of those who experienced battles or skirmishes, about eight percent of North Carolina Continental pension applicants reported being at unnamed or unidentified engagements. Among those who named specific battles, nine of the thirty battles stand out. The Battle of Brandywine in 1777 is the most prevalent battle among North Carolina Continental pension applicants. Twenty-seven percent of men who reported being in a military engagement reported being at this battle. Most of these men were at the subsequent Battles of Germantown and Monmouth, representing the fourth and second most prevalent battles among pension applicants. Slightly over sixty percent of these same men were later at the third most prevalent battle, Charleston in 1780. Only twenty-three percent of the men present at one of these previous four battles were present at the fifth most prevalent battle, Eutaw Springs in September 1781 (Figure 7).

Of those who experienced battles or skirmishes, about eight percent of North Carolina Continental pension applicants reported being at unnamed or unidentified engagements. Among those who named specific battles, nine of the thirty battles stand out. The Battle of Brandywine in 1777 is the most prevalent battle among North Carolina Continental pension applicants. Twenty-seven percent of men who reported being in a military engagement reported being at this battle. Most of these men were at the subsequent Battles of Germantown and Monmouth, representing the fourth and second most prevalent battles among pension applicants. Slightly over sixty percent of these same men were later at the third most prevalent battle, Charleston in 1780. Only twenty-three percent of the men present at one of these previous four battles were present at the fifth most prevalent battle, Eutaw Springs in September 1781 (Figure 7).

POSSESSIONS & OCCUPATIONS

Beginning in 1820, Continental pension applicants were required to submit schedules of their income and assets.[13] About forty-five percent of North Carolina Continental pension applicants provided lists of their property and thirty-six percent provided their occupations. Of those who provided property information just over twenty-five percent indicated owning land at the time of their pension applications. Presumably, these men would have received land grant warrants but many men indicated selling their land in the years preceding their pension application to sustain their families. Only ten of the 409 applications (2.4%) indicate the applicant owned one or more slaves, a low percentage given that “according to the 1860 census (at the height of slave ownership in America), 1 in every 20 (4.9%) adults owned slaves and 1 in every 4 (24.9%) households had slaves.”[14]

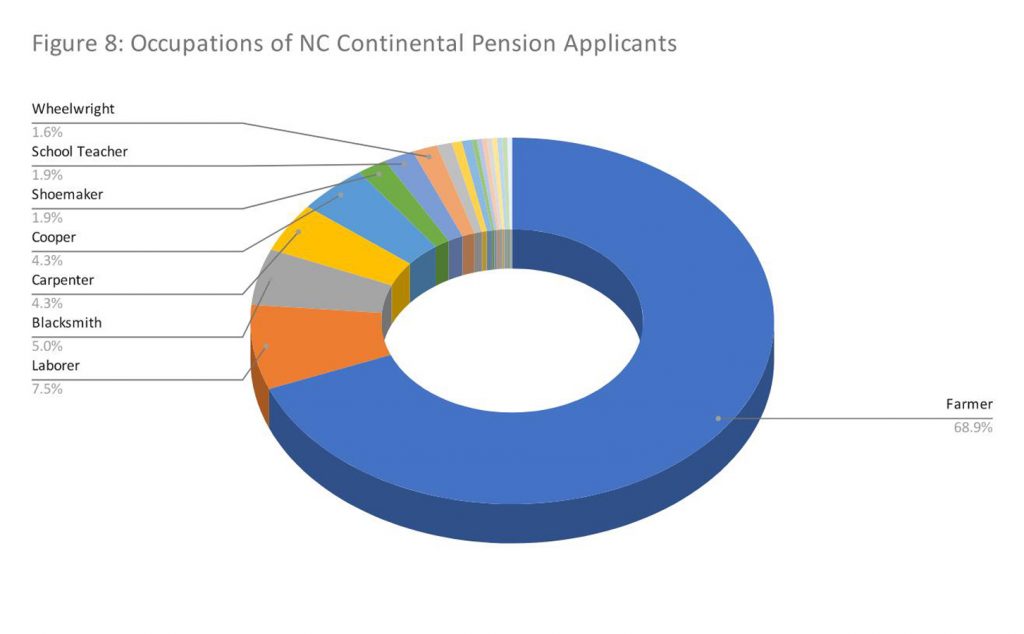

North Carolina Continental pension applicants reported nineteen separate occupations. As might be expected, farming is the most prevalent occupation comprising nearly sixty-nine percent of all men. Common laborer is next at seven and a half percent followed by blacksmith at five percent and carpenter and cooper at four percent each. Other occupations include shoemaker, school teacher, wheelwright, mason, ropemaker, tailor, fisherman, preacher, boatman, sailor, cabinetmaker, skinner, hatmaker, and miller (Figure 8).

LITERACY

There is some uncertainty about the accuracy of determining literacy rates from pension applications. In many instances, court officials signed the names of applicants who were not literate or were unable to sign their applications. That said, forty percent of North Carolina Continental applicants signed their names on their pension documents. This percentage among Continentals contrasts with those of the militia/state troops of whom fifty-three percent signed their applications.

FREE “OTHER” MEN OF COLOR

Almost seven percent of North Carolina Continental pension applicants studied in this work have been identified as free “other” men of color.[15] These determinations were made from the man’s race noted in the application, cross-referencing pension applications with Federal Census data and published rosters. Seven percent is exceptionally high given that only one percent of the North Carolina population in the 1790 Federal Census were free people of color. The northeastern counties of the state were comparatively heavily populated with free African Americans, ranging between four and eight percent of the population.[16] Indeed, among the men that provided their place of enlistment, seventy percent were from the northeastern counties of the state.

There are several possible explanations for the disparity noted above. The most straight-forward would be that free men of color served in the Continental Line at higher rates than their proportion of the population. Another explanation could be that most of these free men of color moved out of the state before the 1790 Census and, thus, the one percent figure does not accurately reflect the demographics of the population during the war; this explanation may be discounted as eighty-seven percent of free black men remained in the state after the war.[17] Seventy-seven percent of these Continental free men of color who filed applications filed them from North Carolina. A third, perhaps more plausible explanation, would be that these free men of color applied for pensions at higher rates due to their financial need which appears to be more pronounced than white applicants. Some data in pension applications supports this rationale. If literacy (or the ability to sign one’s name) can be a relative indicator of wealth, only eleven percent of these free men of color were literate enough to sign their applications whereas forty percent of the whole signed their names. Likewise, only ten percent of these free men of color owned land at the time of their applications whereas twenty-four percent of the whole sample of men did. While these explanations are plausible they are also speculative. Clearly, more research is needed in this area.

The most interesting personal story in the pension applications among these men is that of Drewry Tann of Wake County. Tann was kidnapped as a small boy and taken west to be sold into slavery. His parents contacted a local magistrate who pursued the rogues and apprehended them. Tann’s parents, as a result, offered him as an indentured servant to the magistrate. Several years later when the magistrate was drafted he offered to release Tann from his servitude if he would be his substitute. Tann served the magistrate’s term in South Carolina in 1781 and 1782.[18]

HEIGHT AND COMPLEXION

Size rolls contain demographic data generally not found in pension applications. As the name implies, these documents recorded not only the soldiers’ height or “size” but other personal information such as their age at their time of enlistment. In some rolls, the soldier’s “complexion,” occupation, and place of enlistment and birth were also recorded. The average height of these men was five-foot, seven and a half inches. The range of heights varies from four-foot, eight inches to six-foot, two inches tall. The overwhelming majority (eighty-eight percent) were between five-foot three and five-foot eleven inches tall.

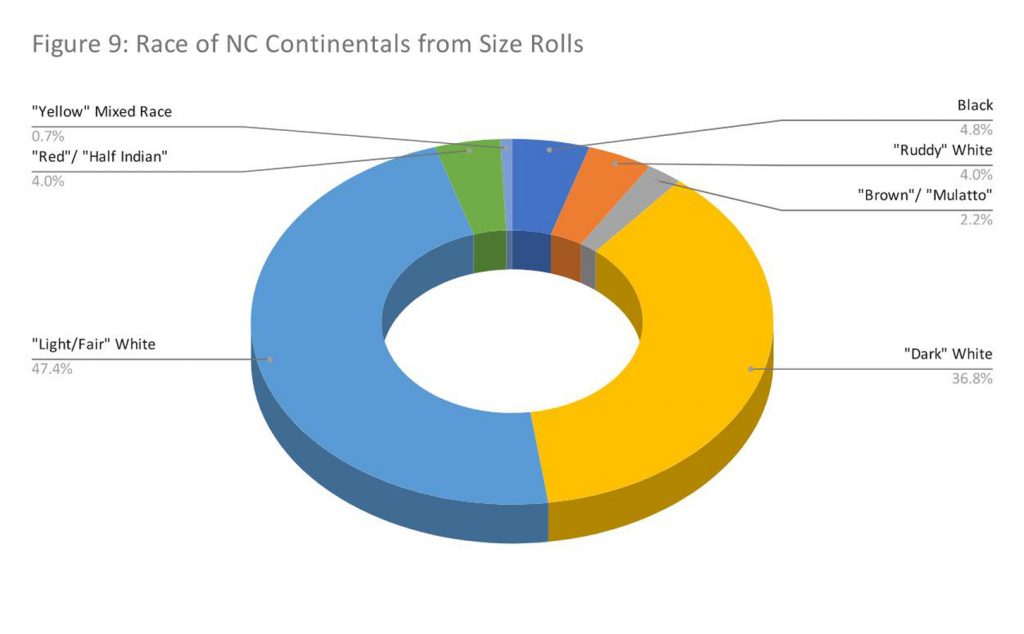

Size rolls also indicate the “complexion” (or more accurately the race) of 272 men. About eighty-eight percent of the men were white, being described as “fair”, “dark”, or “ruddy.” Almost five percent were listed as “black.” Two percent were listed as “brown” or “mulatto.” Another four percent were listed as “red” or “half-Indian.” Just under one percent were listed as “yellow,” likely a reference to men of mixed race (Figure 9). Similar to the pension applicants who were free men of color, the high percentage of these non-white men in these compiled size rolls far exceeds their proportion of the North Carolina population at large. As these men did not file pension applications the disparity cannot be attributed to the men filing for pensions at higher rates than white men. Eighty-three percent of these men were from the northeastern counties of the state where there were, as noted above, very high percentages of free African Americans. Excluding those men who might be Native American the percentages, while still high, would somewhat align with the six to eight percent of free African Americans in northeastern counties.

PRISONERS OF WAR

Just over twenty-four percent of North Carolina Continental pension applicants were made prisoner during the war. This percentage is double the twelve percent of the militia/state applicants taken prisoner. Nearly all of these North Carolina Continental applicants were captured at Charleston. Among all Continentals captured there, those from North Carolina accounted for twenty-six percent of the total.[19] Overall, among all Continental prisoners in the South from all states, less than twenty percent (740 men) were ultimately exchanged in 1781. Some 800 had died in captivity, 950 joined Crown naval or army forces, 1,000 escaped, with the fates of 400 men unknown (these men likely either died in captivity or escaped).[20] Only two widows of North Carolina Continentals who died in captivity filed pension applications for their husbands’ service. One woman revealed her husband died in Virginia. He survived over a year in captivity (very likely on a prison ship) only to die shortly after being exchanged.[21] Another widow revealed that in addition to her husband dying in captivity she had six brothers serve in the war, two of whom died with two others being wounded.[22]

At least 852 American prisoners taken in the southern states joined the British army or navy. More than 500 of these men joined the Duke of Cumberland’s Regiment of Carolina Rangers which was raised in 1781 specifically from American prisoners of war. A critical recruitment component of this regiment, advertised as such, was that the men would not fight against their American compatriots.[23] After raising men from prison barracks and ships, the regiment sailed from Charleston in 1781 and served in Jamaica until 1783. From the available muster rolls of 1783, just before the unit’s disbandment, over twenty-one percent were North Carolina Continentals, the second highest state represented after Virginia’s forty-seven percent. Remarkably, at least fifteen of these men who were in the North Carolina Continental Line and later in the Duke of Cumberland’s regiment, filed Federal pension applications. At least another seven North Carolina pension applicants served with the British navy and at least another five appear to have served in British provincial units.

Quite consistent in the pension applications of these North Carolina soldiers who served in the Duke of Cumberland’s regiment (and navy and provincial units) was the purposeful omission of their British service. Thirteen of the fifteen men noted a fairly consistent story of being made prisoner, then being “carried” to Jamaica or Nova Scotia until the “peace was made,” leaving out the fact that they joined the British army. Of the two men who admitted joining the British army, one admitted to it only after an accusation was made regarding his service by one of his neighbors in North Carolina.[24] The other man admitted in his pension application that he felt abandoned on the prison ships and joined the British after suffering “without Money and Clothes, eaten up with lice and rotten with dirt I laid down at night the same as I walked about all day neither Blankets nor anything but the hard boards to rest upon.”[25]

About twenty-seven percent of North Carolina Continental applicants who were prisoners of war ultimately escaped their captivity. The vast majority of these prisoners escaped in the days, weeks, and months after the surrender of Charleston. Among these men are a few who, in what appears to be more than an isolated incident, changed out of their Continental uniforms to be paroled as militiamen after the surrender of Charleston. Of the forty-four men who escaped, only ten (or twenty-two percent) reported returning to service with their original unit or another Continental or militia unit. Five pension applicants reported being made prisoner twice during the war. One of these men spent fifteen months aboard a prison ship, was exchanged in 1781, and then shortly thereafter was captured again by Loyalist Col. David Fanning. The man was ultimately paroled due to ill health from his previous captivity.[26]

LOCATION OF PENSION APPLICATIONS

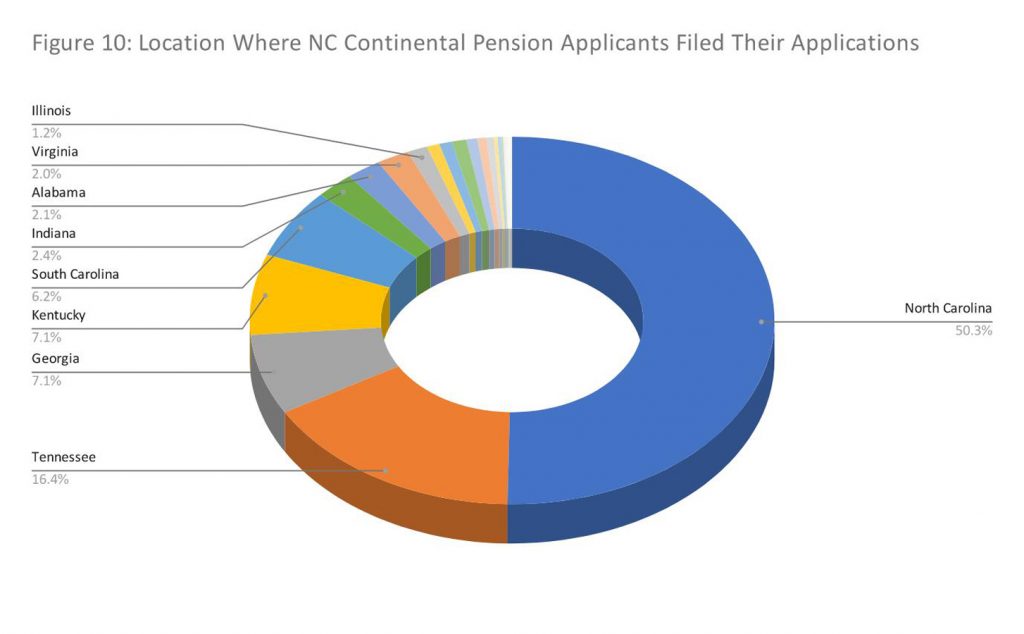

Just over fifty percent of North Carolina Continental pension applicants (or their families) filed applications in North Carolina (Figure 10). This contrasts with the thirty-nine percent of North Carolina militiamen who filed their applications from within the state. North Carolina Continentals filed applications from twenty-three different states which is slightly more than the twenty recorded from a compilation of militia pension applications. Tennessee was the most prevalent out-of-state filing location with sixteen percent for Continentals and twenty-three percent for the militia applicants. Similarly, the second to fourth most prevalent out-of-state filing locations for both sets of applicants are Georgia, Kentucky, and South Carolina respectively.

CONCLUSION

The pension applicants studied here represent about ten percent of the total number of men who served in the North Carolina Line. As with the state’s militia/state troops, it is unfortunate that we may never know as much about the vast majority of soldiers who did not file pension applications as we do about those who did. After compiling all of the research for these two groups of North Carolina soldiers one obvious question remains. To what extent are those who filed applications different from those who did not? Were these pension applicants representative of the larger group of North Carolina soldiers or were they somehow a segment apart from the larger group of men? There are indications in the data that North Carolina pensioners were, perhaps, less literate and financially well-off than the population at large. There very well could be other differences, hopefully, to be addressed by future research and data technology.

One of the objectives of this project was that others may be inspired to undertake similar projects with the pension applications of other states. Applications of men who served in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Virginia have been digitally transcribed and made readily available online, making the process easier for those states. From a practical perspective, compiling pension data from South Carolina and especially Georgia would be the least labor-intensive projects for researchers wanting to engage in this work, because there are far fewer applications to review than those of North Carolina and Virginia. The pension applications of the men from other states are there; their personal and collective stories are waiting to be told.

The author would like to thank Will Graves and C. Leon Harris for their insights on Federal Pension applications which form the basis of this work. He would also like to thank W. Trevor Freeman for providing his time, research material, and expertise on the Black Patriots of the American Revolution.

[1]Hugh F. Rankin, The North Carolina Continentals(Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 21.

[4]J.D. Lewis, North Carolina Patriots, 1775-1783: Their Own Words, Volume I, The North Carolina Continental Line(Little River, South Carolina, eBook, 2012), vi.

[5]Rankin, The North Carolina Continentals, 140.

[6]Lawrence E. Babits and Joshua B. Howard, Fortitude and Forbearance: The North Carolina Continental Line in the Revolutionary War, 1775-1783 (Raleigh: Dept. of Cultural Resources, 2004), 8-9.

[7]Lewis,North Carolina Patriots, v.

[8]Rankin, The North Carolina Continentals, 124.

[9]Lewis, North Carolina Patriots, viii.

[10]Pension application of George Combs (S41497), Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters, https://revwarapps.org/. All pension applications in this article were obtained from this source. All applications were transcribed by Will Graves or C. Leon Harris.

[11]118 pension applicants noted their place of birth. Compiled information from the numerous size rolls of North Carolina Continentals yielded 156 places of birth.

[12]There are several indications that a number North Carolina Line pension applicants at the beginning of the war served a six-month term and later enlisted for a thirty month term. This may explain the relatively low number of men noted as serving a six month term on Figure 4.

[13]Will Graves, An Overview of Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Legislation and the Southern Campaigns Pension Transcription Project, Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters, revwarapps.org/revwar-pension-acts.htm.

[14]Joseph T. Glatthaar, Soldiering in the Army of Northern Virginia: A Statistical Portrait of the Troops Who Served under Robert E. Lee (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011), Kindle Edition, 9.

[15]The reference to “other” or “other free” persons is derived from the terms used in Federal Census data which tabulated the number of whites, slaves, and other free persons living in each household. These terms, unfortunately, do not make a distinction between someone who would today be considered African-American, mixed race, or Native American.

[16]Paul Heinegg, List of Free African Americans in the Revolution: Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware. www.freeafricanamericans.com/introduction.htm.

[17]W. Trevor Freeman, “North Carolina’s Black Patriots of the American Revolution”, Master’s Thesis, East Carolina University, 2020, 92.

[18]Pension application of Drewry Tann (S19484).

[19]Carl P. Borick, Relieve Us of This Burthen: American Prisoners of War in the Revolutionary South, 1780-1782 (Columbia, SC: The University of South Carolina Press, 2012), 4.

[21]Pension application of Abram Hay (W17262).

[22]Pension application of Thomas Blanchett (W20395).

[23]Borick, Relieve Us of This Burthen, 33.

4 Comments

Good work

John, thank you. I’ve submitted a companion article for Georgia soldiers. There are some striking differences but also similarities. I’ve just started compiling data for South Carolina soldiers.

I am very interested in accumulating a list of North Carolina soldiers that fought in the battle of Stony Point. You appear to have identified a number of them who cited Stony Point in their pension applications. Can I get the list of their names and units from you?

I greatly appreciate whatever you can share.

Thank you –

John F Polk

Descendant of Major Hardy Murfree

John, please send me an email at: do***********@ho*****.com

I will send you the names of the NC pension applicants from that battle. At least the ones I’ve documented.