The Battle of Eutaw Springs, South Carolina, on September 8, 1781 was the last major open-field battle of the Revolutionary War and perhaps its most savage. The close-quarter fighting that occurred there ranks among the bloodiest and most intensely contested military encounters in young America’s quest for independence.[1] It has, however, been eclipsed in historical memory by the climactic military event of the conflict—the siege at Yorktown, Virginia, and subsequent surrender of a British army that overshadowed the struggle in South Carolina.

Overview

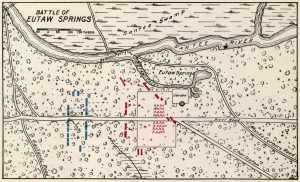

Eutaw Springs Battleground Park, near today’s Eutawville in Orangeburg County, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970. The site is some fifty miles northwest of Charleston, which at the time of the battle was occupied by British troops for well over a year. At Eutaw Springs some 2,200 Americans—Continental regulars from Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and Delaware; state troops from South Carolina; and militia from North and South Carolina, supported by two cavalry units and four cannon—under Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, a Rhode Island Quaker-turned-Patriot warrior, collided with the last of His Majesty’s field armies operating south of Virginia. The latter comprised about two thousand British regulars and Loyalists under Lt. Col. Alexander Stewart: the 63rd and 64th Regiments of Foot; the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants); grenadiers and light infantry drawn from the 3rd, 19th, and 30th Regiments of Foot; Loyalist units from New York and New Jersey; a single cavalry unit; and five cannon.[2] The combatants were bathed in blistering heat during an engagement that lasted between three and four hours, one of the longest of the war, and over 1,400 were killed, wounded, captured, or missing—consuming about 40 percent of Stewart’s army and a quarter of Greene’s.[3]

Shortly before this encounter Greene had written, “we must have victory or ruin, nor will I spare anything to obtain it.”[4] As soon as it was over, each side professed to be the victor, and the question of who won has been a source of contention ever since.[5] A confluence of factors underlay Greene’s decision to withdraw from the battlefield: his men’s increasingly urgent thirst for water after their extended march preceding the action and several hours of fighting that carried the threat of heat stroke; and the need to reorganize his force in the wake of heavy losses to his officer corps, even as he intended to further challenge the enemy by attempting (unsuccessfully, as it would turn out) to cut off their anticipated retreat to Charleston.[6] Sergeant Major William Seymour of the Delaware Regiment echoed these concerns when he recounted that the rebel soldiers “were so far spent for want of water, and our Continental officers suffering much in the action, rendered it advisable for General Greene to draw off his troops, with the loss of two 6-pounders.”[7] For the British, the battle arguably yielded a tactical success because they held the field, but it was a strategic setback. It sliced deeply into their limited troop presence in the Carolinas and failed to neutralize Greene’s army or rally public support for the royal cause. The same could be said of Greene’s earlier confrontations with the King’s forces that year—at Guilford Courthouse (March 15), Ninety Six (June 19), and Hobkirk’s Hill (April 25).[8]

The Cost

To General Greene, who had a horse shot from under him at Eutaw Springs, this was “the most obstinate fight” and “by far the hottest action I ever saw.”[9] Col. Otho Holland Williams of Maryland, who commanded a brigade and was wounded in the battle, described “the field of battle” as being at one point “rich in the dreadful scenery which disfigures such a picture.”[10] Capt. John Hughes of the South Carolina militia, a veteran of numerous engagements, avowed that “This was the severest action I was ever in.”[11] Jim Capers, an enslaved drum major (who would be freed after the war) serving in the South Carolina Militia under Brig. Gen. Francis Marion (known to future generations as “the Swamp Fox”), “was wounded, in four Different places, one on the head & two on the face with a sword and one on the left side with a ball.”[12] The loss of American officers may have exceeded that in any other engagement of the war, with sixty out of one hundred killed, wounded, or captured,[13] while Colonel Stewart reported twenty-nine casualties among his officers.[14] Lt. Hector Maclean, with the 84th Foot, wrote of his first battlefield experience that day: “Were I a veteran I would venture to Say never was battle fought with a more Strenuous, a more laboured obstinacy, but as this was my first it might with propriety be answered I only thought so having never Seen any other.”[15]

Who Won?

After this slugfest, the civil war raging between Loyalists and Whigs in the South continued into the following year, but the Patriot faction controlled the countryside and limited the redcoats’ activity in the interior to raids for food and forage.[16] Throughout the Carolinas and Georgia, British authority was now limited to the major seaports of Charleston, Savannah, and Wilmington; the troops occupying them—who had entertained visions of crushing all resistance in this region just the year before—would evacuate all three ports by the end of 1782. According to Lt. Col. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee (father of Confederate general Robert E. Lee), who led the mixed cavalry and infantry of the 2nd Partisan Corps or Lee’s Legion, “The battle of the Eutaws evidently broke the force and humbled the spirit of the royal army; never after that day did the enemy exhibit any symptom of that bold and hardy cast which had hitherto distinguished them.”[17]

Be that as it may, we are told by one study of the battle that most historians credit the British with a win at Eutaw Springs.[18] Modern-day chroniclers have differed on this point. For example, one asserts that the results of this contest and the others fought by Greene as commander of the Southern Department of the Continental Army were decisively in favor of the Americans.[19] Another argues that this affair began and ended in utter confusion with both sides devastated by the magnitude of their losses, a large share of them officers, and that Greene won none of his battles in the Carolinas.[20] A third contends that a clearer example of a draw could not be had, as the rebels took several hundred prisoners and pushed their adversary back but did not break Stewart’s army, which was too enfeebled to pursue its opponent and barely held its position.[21] Another simply terms the result of this and Greene’s other battles indecisive.[22] And yet another tries to have it both ways, observing that Greene was denied a victory at Eutaw Springs that would have crowned his Southern campaign with the laurels he richly deserved, but then later claiming the Americans had clearly prevailed.[23]

Colonel Williams of Maryland argued that the “evidence [of victory] is altogether on the American side” as it regrouped after evacuating the field on the 8th and the following day Greene dispatched Marion’s and Lee’s units in a fruitless pursuit of the retreating enemy. The latter “relinquished the country it commanded” and withdrew to Charleston Neck.[24] Still, Williams acknowledged that Greene’s effort to score an unambiguous success was foiled by devastating fire from a formidable defensive position which the British established in a large, two-story brick house long believed to have been owned by Patrick Roche.

The Brick House

In a field to the west of Eutaw Springs stood the Roche dwelling with its garden and a palisaded fence extending to Eutaw Creek, a tributary of the Santee River. (The creek was submerged under Lake Marion, the largest lake in South Carolina, when the Santee was dammed in the 1940s.) This sturdy building resisted small-arms fire and commanded an open field extending to the west, south, and east.[25] Once barricading themselves inside, a Loyalist detachment—the New York Volunteers under Maj. Henry Sheridan—fusilladed any exposed rebels, taking particular advantage of the upper windows. According to Colonel Williams, “The Enemy were defeated and obliged to retire to their camp which had the advantage of a large Brick House in which many of them found refuge from our fire and annoyed us from the windows which circumstances alone saved them from a total Rout, and in all probability, the whole of them from being made prisoners.”[26] This improvised fortress played a role similar to the Chew Mansion at the Battle of Germantown in thwarting an attack.[27]

In many cases, the Americans taking fire from the Roche house were officers who had advanced through the British camp where tents were still standing, even as most or all of their men hung back and sought refreshment from whatever temptations they could find in those tents or concealment therein from enemy volleys.[28] Colonel Williams reported that when the officers “proceeded beyond the encampment, they found themselves nearly abandoned by their soldiers, and the sole marks for the party who now poured their fire from the windows of the house.”[29] One of the soldiers there that day, James Magee, explained that “the British were driven beyond their baggage, when our men commenced rummaging their tents, drinking rum &c &c which the enemy discovering, came back upon us, & drove us back into the woods.”[30]

The Blackjack

John Chaney, serving with a cavalry contingent composed of the 1st and 3rd Continental Light Dragoons under Lt. Col. William Washington (George’s distant cousin), recalled the maelstrom of combat into which he plunged when the colonel was captured during a charge against the three hundred or so elite light infantry and grenadiers defending the British right flank under Maj. John Majoribanks (pronounced “marshbanks”). The latter were posted behind a thicket of blackjack (a dense formation of scrub oak) lining Eutaw Creek, which proved impenetrable to Washington’s horsemen as well as to Col. Wade Hampton’s cavalry from the South Carolina State Troops who joined the charge. “Washington jumped his horse into the midst of the enemy and was suddenly taken prisoner,” as Chaney described it. He continued,

A British soldier appearing to be in the posture of attempting to stab Colonel Washington, one of his men rushed forward and cut him down at one blow. Washington being a prisoner, and his men mingled in confusion with the enemy, and not knowing what else to do, this applicant with about twenty-five retreated and left the field.

Chaney related that “Afterwards they were joined by five of Washington’s other soldiers, stating that they only escaped out of a great many who attempted to charge through the enemy’s lines.”[31] Few visual representations of this engagement have come down to us, and the one by the noted artist Don Troiani of a sword-wielding Colonel Washington leading his brave but futile charge is probably the most widely known modern-day image of the battle.[32]

Writing to Gov. John Rutledge of South Carolina on September 9, Greene referenced the twin obstacles of topography—the Roche house and the thicket of blackjack—that in his opinion had enabled the other side to avert a catastrophic defeat. According to the rebel commander, “We took between three and four hundred prisoners, and had it not been, for the large Brick Building, at the Eutaw Spring, and the peculiar kind of Brush that surrounds it, we should have taken the whole Army prisoners.”[33] The resistance offered by Sheridan’s Loyalists in the Roche house, Majoribanks’s light infantry and grenadiers on the British right flank, and Maj. John Coffin’s cavalry unit on their left flank, gave Stewart the time he desperately needed to organize a successful counterattack in the center.[34]

Kirkwood’s Account

Capt. Robert Kirkwood of the Delaware Continental Regiment, whose men were in the “Corps de Reserve” on this day, explained that they were positioned behind a front line of militia from the Carolinas led by General Marion and Brig. Gen. Andrew Pickens, with Colonel Henry Lee’s cavalry on their right flank and mounted infantry on their left, and a second line “with North Carolina regulars, Virginians, & Marylanders.” He reported that “we arrived within mile of [the British] Encampment, where we met their front line, which soon brought the action general.” The Delawares pushed back the opposing “first, and Second Lines, took upwards of 500 prisoners.” Ultimately, “our men were so far spent for want of water, and our Continental Officers suffering much in the Action, rendered it advisable for Genl. Green to Draw off his Army, with the Loss of two 6 pounders . . . Found our Army had withdrawn from the Field, made it necessary for us Likewise to withdraw.” Although Greene’s soldiery retired first, the Delawares gained a measure of redemption when they “brought off one of the Enemy’s three pounders, which with much difficulty was performed through a thick wood for near four miles, without the assistance of but one Horse. We got to the Encamping Ground which we left in the morning about two in the evening.”[35]

The British Perspective

Even before this affray, Greene had encapsulated his troops’ combat experience during their remarkable Southern campaign in one famously memorable sentence. Reflecting on his performance in wearing down their adversary by making British victories so costly while preserving the integrity of his army, the wily strategist wrote: “We fight, get beat, rise and fight again.”[36] Colonel Stewart insisted that the rebel general had been beaten once more on September 8, reporting to General Cornwallis the following day that he had “totally defeated” Greene.[37] However hyperbolic that judgment may have been, given that his battered force was too weak to risk another engagement, the colonel’s reasoning was plausible to the extent that Greene, not he, had broken off the fight and largely ceded the field by withdrawing to the Americans’ starting point that morning at Burdell’s Plantation seven miles from the battlefield.[38] According to Stewart, the rebels, once repulsed by Majoribanks’s counterattack on their left flank, “gave way in all quarters, leaving behind them two brass six-pounders, and upwards of two hundred killed on the field of action, and sixty taken prisoners, amongst which is Col. Washington, and from every information, about eight hundred wounded, although they contrived to carry them off during the action.” The colonel added that his foe “retired with great precipitation to a strong situation, about seven miles from the field of action, leaving their Cavalry to cover their retreat.”[39] Even Greene conceded that the other side had “really fought worthy of a far better cause.”[40]

Stuart’s missive to Cornwallis complimented the efforts of his officers, in particular those of “Major Majoribanks [who was mortally wounded and today lies buried in the battleground park], and the flank Battalion under his command, [to whom] I think the honor of the day is greatly due.” Claiming to have fought off nearly four thousand Americans—almost twice the size of Greene’s actual strength—Stewart, “a good deal indisposed by a wound which I received in my left elbow,” commended the performance of his supposedly outnumbered contingent:

I hope, my lord, when it is considered such a handful of men, attacked by the united force of Generals Greene, [Thomas] Sumter [he was not actually at the battle but the South Carolina State Troops, whose command he had recently relinquished, were], Marion, [Brig. Gen. Jethro] Sumner, and Pickens, and the Legions of Colonels Lee and Washington, driving them from the field of battle, and taking the only two six-pounders they had, deserve some merit.[41]

And British Maj. Frederick Mackenzie remarked that Greene’s report to Congress on the engagement

seems principally designed to gloss over a defeat, by bestowing great praise on all the Officers and troops under his command. Greene is however entitled to great praise for his wonderful exertions; the more he is beaten, the farther he advances in the end. He has been indefatigable in collecting troops, and leading them to be defeated.[42]

Accolades

While overseeing the siege of Yorktown, Washington acknowledged Greene’s claims of success at Eutaw Springs by congratulating him “upon a victory as splendid as I hope it will prove important.”[43] According to John Adams, writing more than a month after Cornwallis’s surrender, “General Greene’s last action in South Carolina . . . is quite as glorious for the American arms as the capture of Cornwallis. The action was supported, even by the militia, with a noble constancy. The victory on our side was complete.”[44] Not to be outdone, Congress awarded the presumed victor a gold medal—one of only six medals authorized by Congress for battles or campaigns of the Revolutionary War.[45] And today the bronze doors of the House of Representatives in the U.S. Capitol Building include as one of their six panels of history the presentation of the medal and a flag to Greene by the Continental Congress for the Battle of Eutaw Springs.[46] Although such adulation may be exaggerated given the engagement’s ambiguous outcome, it conferred upon the enterprising Rhode Islander the recognition he had long sought as a battlefield commander.[47] He yearned to win an illustrious victory that would earn him the plaudits of his contemporaries and posterity, and when circumstances denied him such a triumph he lay claim to it anyway at Eutaw Springs.[48] Brig. Gen. (soon to be Maj. Gen.) Henry Knox’s approbation of Greene’s efforts in the South perhaps rang the loudest, noting that he had “performed Wonders” without “an army, without Means, without anything.”[49]

The common soldier who became embroiled in this clash of arms received no such acclaim, for as Joseph Plumb Martin noted in his memoir of service in the Connecticut militia and the Continental Army, “Great men get great praise, little men nothing.”[50] Even so, Philip Freneau, in his second volume of Poems Written and Published During the American Revolutionary War, memorialized the Americans who fell on that September day. His elegy begins, “At Eutaw Springs the Valiant Died” and ends with this verse: “Now Rest In Peace, our patriot band; Though far from nature’s limits thrown, We trust they find a happier land, A brighter sunshine of their own.”[51]

Final Thoughts

Regardless of who won, the story of the ferocious brawl that enveloped this South Carolina battleground graphically illustrates the brutality of war during a grueling contest for American independence. In particular, it gives vivid testimony to the deprivations suffered by the common soldiers on each side, the horrors of civil war that befell Patriots and Loyalists alike, and the enormous sacrifice in blood and treasure incurred by Great Britain in its ill-fated quest to defeat a colonial insurrection in a distant land from which many of its sons would never return.[52] The specter of carnage on this and other fields was foreseen by Edmund Burke, the great British orator and Member of Parliament, when he warned his fellow lawmakers in 1775 of the consequences for America—and implicitly for those fighting on both sides—likely to ensue from Britain’s military action against her recalcitrant subjects: “The thing you [will have] fought for, is not the thing which you [will] recover; but deprecated, sunk, wasted, and consumed in the contest.”[53]

Perhaps the stone marker that was erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution at Eutaw Springs Battleground Park in 1912 provides the most succinct and accurate assessment of the outcome there: “Neither side was victorious, but the fight was beneficial to the American cause.” To any history buff’s dismay, the ultimate triumph at Eutaw Springs belongs to the tide of residential and commercial development that has encroached upon, and in some cases engulfed, many a Revolutionary War and Civil War battlefield. Most of where the action occurred on that long-ago September day has been overtaken by a modern neighborhood dating largely from the 1960s. Except for the small roadside park with its verdant canopy, there is little to see of the site where the last major battle of the War for Independence was fought.[54]

[1]Theodore P. Savas and J. David Dameron, A Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution (Eldorado Hills, CA: Savas Beattie LLC, 2013), 329.

[2]Most historians maintain that the opposing armies in this battle were at about equal strength and that the number of soldiers on each side was between 1,800 and 2,400. See John Buchanan, The Road to Charleston: Nathanael Greene and the American Revolution (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2019), 218. For a discussion of troop estimates on both sides at Eutaw Springs as suggested by various primary and secondary sources, see The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, ed. Dennis M. Conrad (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 9:333n2.

[3]“Eutaw Springs,” American Battlefield Trust, www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/eutaw-springs. This site characterizes the result as a British victory and indicates total casualties of 1,461, including 882 British and Loyalists, and 579 Americans killed, wounded, and missing (including captured). By comparison, the losses reported by Greene and Stewart of 522 and 692, respectively, were quite conservative, especially the latter. See Robert M. Dunkerly and Irene B. Boland, Eutaw Springs: The Final Battle of the American Revolution’s Southern Campaign (Columbia, SC: The University of South Carolina Press, 2017), 112-113. Captain Robert Kirkwood of the Delaware Continental Regiment reported 525 American casualties. See Robert Kirkwood, The Journal and Order Book of Captain Robert Kirkwood of the Delaware Regiment of the Continental Line, ed. Rev. Joseph Brown Turner (Wilmington, DE: The Historical Society of Delaware, 1910. Reprint: Sagwan Press, 2015), 24. To put these tallies in perspective, Robert Middlekauff notes the notorious unreliability of Revolutionary War casualty statistics, in The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 502. The Battle of Eutaw Springs was no exception, according to William Johnson in Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene, Major General of the Armies of the United States in the War of the Revolution (Charleston, SC: A.E. Miller, 1822), 236.

[4]Nathanael Greene to Henry Lee, August 22, 1781, in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 9:223.

[5]Dunkerly and Boland, Eutaw Springs, xi.

[6]Christine R, Swager, The Valiant Died: The Battle of Eutaw Springs, September 8, 1781 (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 2006), 115-118.

[7]William Seymour, “A Journal of the Southern Expedition, 1780-1783,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 7:4 (1883): 386.

[8]Matthew H. Spring, With Zeal and with Bayonets Only: The British Army on Campaign in North America, 1775-1783 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), 279.

[9]Greene to George Washington, September 17, 1781. Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-06976.

[10]Otho Holland Williams, “Battle of Eutaw,” in Documentary History of the American Revolution … Chiefly in South Carolina, ed. R.W. Gibbes (Columbia, SC: Banner Steam-Power Press, 1853), 3:152.

[11]Dunkerly and Boland, Eutaw Springs, 12.

[12]Pension Application of Jim Capers, R1669, transcribed and annotated by C. Leon Harris, posted on Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters, http://revwarapps.org/r1669.pdf. See also Jim Piecuch, “Francis Marion at the Battle Of Eutaw Springs,” in Journal of the American Revolution, June 4, 2013,

allthingsliberty.com/2013/06/francis-marion-at-the-battle-of-eutaw-springs/.

[13]Theodore Thayer, Nathanael Greene: Strategist of the American Revolution(New York: Twayne Publishers, 1960), 380.

[14]Alexander Stewart to Charles Cornwallis, September 9, 1781, in Documentary History of the American Revolution, 1:39.

[15]Hector Maclean, September 12, 1781 (Maclean of Lochbuie Muniment. GD174/2154/7. Scottish Records Office, Edinburgh), in Dunkerly and Boland, Eutaw Springs, 78.

[16]Buchanan, The Road to Charleston, 234.

[17]Henry Lee, Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States (New York: University Publishing Company, 1870), 540.

[18]Swager, The Valiant Died, 135.

[19]Theodore Thayer, “Nathanael Greene: Revolutionary War Strategist,” in George Washington’s Generals, ed. George Athan Billias (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1964), 132.

[20]Christopher Hibbert, Redcoats and Rebels: The American Revolution through British Eyes (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1990), 312-313.

[21]Dunkerly and Boland, Eutaw Springs, xii.

[22]Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris, eds. The Spirit of ‘Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participants (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1967), 1185.

[23]Page Smith, A New Age Now Begins: A People’s History of the American Revolution (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1976), 2:1691, 1825.

[24]Otho Holland Williams, in Documentary History of the American Revolution, 3:157.

[25]Ibid., 3:147. For a discussion of geographic interpretation issues relating to the Roche property and adjacent roads at the time of the battle, see Stephen John Katzberg, “Mapping the Battle of Eutaw Springs: Modern GIS Solves a Historic Mystery,” in Journal of the American Revolution, March 2, 2020, allthingsliberty.com/2020/03/mapping-the-battle-of-eutaw-springs-modern-gis-solves-a-historic-mystery/.

[26]Otho Holland Williams to Elie Williams, September 11, 1781 (General Otho Holland Williams Papers, Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society), in Dunkerly and Boland, Eutaw Springs, xiv.

[27]Smith, A New Age Now Begins, 2:1691.

[28]Buchanan, The Road to Charleston, 229-230.

[29]Otho Holland Williams, in Documentary History of the American Revolution, 3:154.

[30]Pension Application of James Magee, S1555, http://revwarapps.org/s1555.pdf.

[31]John Chaney, Military Pension Application Narrative, in The Revolution Remembered: Eyewitness Accounts of the War for Independence, ed. John C. Dann (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 232.

[32]Battle of Eutaw Springs, 2006 (oil on canvas), Bridgeman Images, www.bridgemanimages.com/en/noartistknown/title/notechnique/asset/3026974. See “William Washington’s Charge at Eutaw Springs,” in Don Troiani, Don Troiani’s Soldiers of the American Revolution (Guilford, CT: Stackpole Books, 2007), 168-169.

[33]Greene to John Rutledge, September 9, 1781, in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 9:308.

[34]The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 9:336-337n14.

[35]Kirkwood, Journal and Order Book, 22-23.

[36]Greene to Chevalier de La Luzerne, April 28, 1781, in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 8:167.

[37]Stewart to Cornwallis, September 9, 1781, in Documentary History of the American Revolution, 136.

[38]Buchanan, The Road to Charleston, 233.

[39]Stewart to Cornwallis, September 9, 1781, in Documentary History of the American Revolution, 138.

[40]Greene to Thomas McKean, September 11, 1781, in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 9:329.

[41]Stewart to Cornwallis, September 9, 1781, in Documentary History of the American Revolution, 139.

[42]Frederick Mackenzie, Diary of Frederick Mackenzie (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1930), 2:673.

[43]Washington to Greene, October 6, 1781, in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 9:429.

[44]John Adams to John Jay, November 28, 1781, in The Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1852), 7:487.

[45]South Carolina General Assembly, Committee to Study the Advisability of Establishing a Bicentennial Commission of the American Revolution for South Carolina to Be Known as the “Spirit of 1776 Commission” (1971), Liberty and Independence, South Carolina and the Founding of the Nation: Second Report of the Committee to Study the Advisability of Establishing a Bicentennial Commission of the American Revolution for South Carolina to Be Known as the “Spirit of 1776 Commission” (Columbia, SC), 6. The Continental Congress authorized medals to be struck in honor of the following battles or campaigns: the Siege of Boston in 1776, Saratoga in 1777, Stony Point in 1779, Paulus Hook in 1779, Cowpens in 1781, and Eutaw Springs. In lieu of a medal, Congress directed that a marble obelisk be erected in recognition of the victory at Yorktown.

[46]“House Bronze Doors,” Architect of the Capitol, www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/art/house-bronze-doors. The bronze doors were designed by the American sculptor Thomas Crawford in Rome in 1855-1857. Upon Crawford’s death, William H. Rinehart executed the models from the sculptor’s sketches in 1863-1867. The models were shipped from Leghorn, Italy, in 1867 and stored in the Crypt of the Capitol Building until 1903, when they were cast by Melzar H. Mosman of Chicopee, Massachusetts. The doors were installed in 1905 at the east portico entrance of the House wing.

[47]Terry Golway, Washington’s General: Nathanael Greene and the Triumph of the American Revolution (New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 2006), 286.

[49]Theodore Thayer, Nathanael Greene: Strategist of the American Revolution, 381.

[50]Joseph Plumb Martin, Memoir of a Revolutionary Soldier: The Narrative of Joseph Plumb Martin (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 2006), 54.

[51]Philip Freneau, “To the Memory of the Brave Americans, under General Greene, in South Carolina, who fell in the Action of September 8, 1781,” in Poems Written and Published During the American Revolutionary War, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: From the Press of Lydia R. Bailey, no. 10, North-Alley, 1809), 2:71.

[52]By at least one estimate, Great Britain suffered forty thousand casualties and expended fifty million pounds in the course of the war. See Joseph Ellis, Revolutionary Summer: The Birth of American Independence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013), 178.

[53]“The Speech of Edmund Burke, Esquire, on Moving his Resolutions for Conciliation with the Colonies, March 22d, 1775,” in The American Revolution: Writings from the Pamphlet Debate (New York: The Library of America, 2015), 2:544.

4 Comments

Related to this topic, I am currently transcribing demographic data from all South Carolina Revolutionary War soldiers (about 650 so far). Very prominent among the South Carolina State Troops, enlisted in 1781 who fought at Eutaw Springs, are enlistments from North Carolina. In short (I am finding) almost all of the SC State Troops at Eutaw Springs were enlisted in and lived in Mecklenburg and Rowan counties of North Carolina.

Thank you for that information.

And I missed saying great article, a pleasure to read.

Glad you enjoyed it!