To complement my two studies of the North Carolina Continental Line and militia/state troops, I’ve researched the demographics of the Georgia Continental Line and militia using Federal pension applications.[1]

The colony of Georgia at the beginning of the Revolutionary War consisted only of a series of counties along the Savannah River running from the Atlantic coast northwest to the frontier town of Augusta. In 1770 the colony had an estimated population of only 23,375 people, the fewest of the original thirteen colonies. By 1780, the population had increased two-fold placing the state ahead of the populations of Rhode Island and Delaware.[2]

Georgia’s first Continental regiment was formed in November 1775.[3] By February 1776, Lachlan McIntosh was commissioned colonel and began recruiting men for a single regiment. This first regiment of four small companies required more men than could be raised in the colony.[4] Despite Georgia’s rapid population increase only 3,000 military-aged males lived in the state at the time.[5] To provide the necessary men, Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, then commander of the Southern Department, supported the idea of raising six regiments from neighboring states for service in Georgia.[6] Three additional regiments were subsequently raised largely from men in the Carolinas and Virginia from mid to late 1776.[7] Also raised that year was a Continental regiment of Georgia Light Horse (or Rangers). This unit only loosely served under Continental control. One source notes them as nothing more than “vigilantes” operating independently on the border frontiers of the state.[8] Even with the influx of men from South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, the Georgia Line never numbered more than 1,423 men.[9] Georgia militia and state troops were not very numerous either, never amounting to more than 3,200 men, the apex of which occurred in 1778.[10]

PENSION APPLICATIONS

Federal Pension Applications began in 1818 and continued through the late 1830s. Continental soldiers filed pensions under the 1818 and 1828 Pension Acts while those of the militia and state troops came after the Pension Act of 1832. Generally, Continental pension applications filed under the 1818 and 1828 Acts are shorter and yield less demographic information than those of the militia and state troops. Under the 1818 Act, the applicant needed to prove nine months service or service until the end of the war in a Continental regiment in addition to being indigent or disabled. Under the 1828 Act, the applicant only needed to establish service in the Continental Line until the end of the war. The 1832 Act opened up pensions to all men who served six months or more regardless of whether they were in the militia, state troops, or Continental Line. Applicants from 1832 onward were generally required to answer a series of prescribed questions that began with the applicants’ place and date of birth, their place and method of enlistment (volunteer, draft, or substitute), officers under whom they served, discharge information, and the names of people who could verify their service. In only two demographic areas do Continental applications provide more information: on occupations and property.

Over 4,000 pension applications pertaining to Georgia were reviewed for this work. Of those, 338 were identified as men who had served in a Georgia Continental regiment or militia unit, provided demographic information about themselves and also information about their military service. The data therein represents a small portion (less than 10 percent) of the understood total number of men who served in Georgia service. The analysis, findings, and figures presented here only apply to the data collected from the 338 pension applicants and should not be construed to apply to the entire body of Georgia Revolutionary War soldiers.

Caution is necessary regarding data and descriptions on dates of birth, length of service, and property/land ownership. Pension applicants were likely to be younger because many older soldiers died before having the opportunity to apply for pensions. As the average lifespan in eighteenth-century America was between forty-one and forty-seven years of age, it certainly seems possible, if not probable, that the men studied here represent the younger range of Georgia soldiers. Regarding length of service, some reported only their fixed term of enlistment while others noted the actual number of months they served. Georgia soldiers’ length of service is further clouded by the fact that nearly half of Georgia soldiers served in other states. Given these disparities there is some uncertainty on the accuracy of the mens’ overall time in service. Lastly, based on the descriptions of the mens’ property and the need-based requirements of the 1820 Pension Act it appears that many of these men (at least at the time of their applications) were at the lower economic strata of American society based on their owning very little if any personal property or land.

PLACES AND DATES OF BIRTH

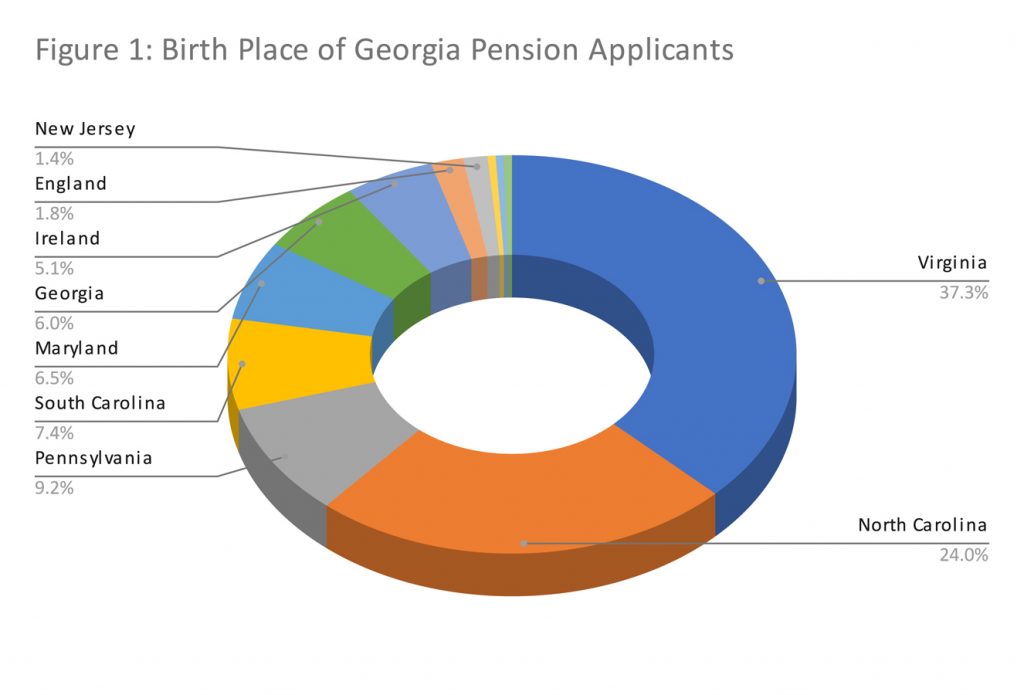

Almost two-thirds of pension applicants who served in a Georgia unit (militia, state troops, state legion, or Continental Line) note their place of birth. A vast majority of these men (94 percent) were not born in the colony of Georgia. Virginia accounts for the highest number of total births at 37 percent. North Carolina was second among all states with 24 percent of the total. Other colonies of birth include Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Maryland, New Jersey and Delaware with percentages ranging from 9 percent to a fraction of a percent each in that order. Foreign births account for nearly 8 percent of all Georgia pension applicants. Ireland is first among these with over 4 percent of the total. Only three other countries are noted: England at nearly 2 percent of all applicants and just one man each born in the Virgin Islands and Germany (Figure 1).

Focusing on Georgia’s Continental and militia units separately reveals a few contrasts in places of birth. Almost 52 percent of men who reported serving in the Georgia Continental Line were born in Virginia. For the Georgia militia, the place of birth which accounts for the highest portion of men is North Carolina with 30 percent. Interestingly, for both the Georgia Continental and militia pensioners those born in the colony account for 6 percent.

Focusing on Georgia’s Continental and militia units separately reveals a few contrasts in places of birth. Almost 52 percent of men who reported serving in the Georgia Continental Line were born in Virginia. For the Georgia militia, the place of birth which accounts for the highest portion of men is North Carolina with 30 percent. Interestingly, for both the Georgia Continental and militia pensioners those born in the colony account for 6 percent.

Georgia pensioner places of birth contrast sharply with those of North Carolina. Eight to ten times more North Carolina pensioners were born in their state than their counterparts in Georgia. Over 44 percent of North Carolina militia and state troops and 52 percent of the Continental Line reported being born in the state versus 6 percent for Georgia. There are similarities, however, in the distribution of out-of-state births. For both North Carolina and Georgia, Virginia accounts for the highest number of out of state births. Likewise, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and New Jersey figure prominently among the remainder of out of state births for Georgia and North Carolina. Comparisons of foreign births are relatively consistent between the two states’ pensioners. Just over 3 percent of North Carolina militia and state troops and 6 percent of Continentals were foreign born. Overall, Georgia’s pensioners reported slightly higher rates of foreign births at almost 8 percent.

The average birth year of all Georgia pension applicants is 1756 (median year of 1757). This is the same average (and median) birth year as North Carolina Continental Line pension applicants. However, these birth dates are one full year earlier than North Carolina militia and state troops applicants who on average were born in 1757 (median year of 1758). There is a disparity when considering Georgia Continentals and militia separately. Georgia Continentals became older by one year with an average birth year of 1755. Georgia militia pensioners are almost three years younger with a birth year very near 1758. Several Georgia pension applicants were fourteen years old when they went into the militia. One young soldier served three terms over three years and was in two battles and one skirmish. He finished all of his military service by the time he was eighteen in 1780.[11] The oldest man in Georgia service to have filed for a pension was forty-four years old when he entered the Georgia Continental Line in Virginia in 1777.[12]

PLACE OF ENLISTMENT

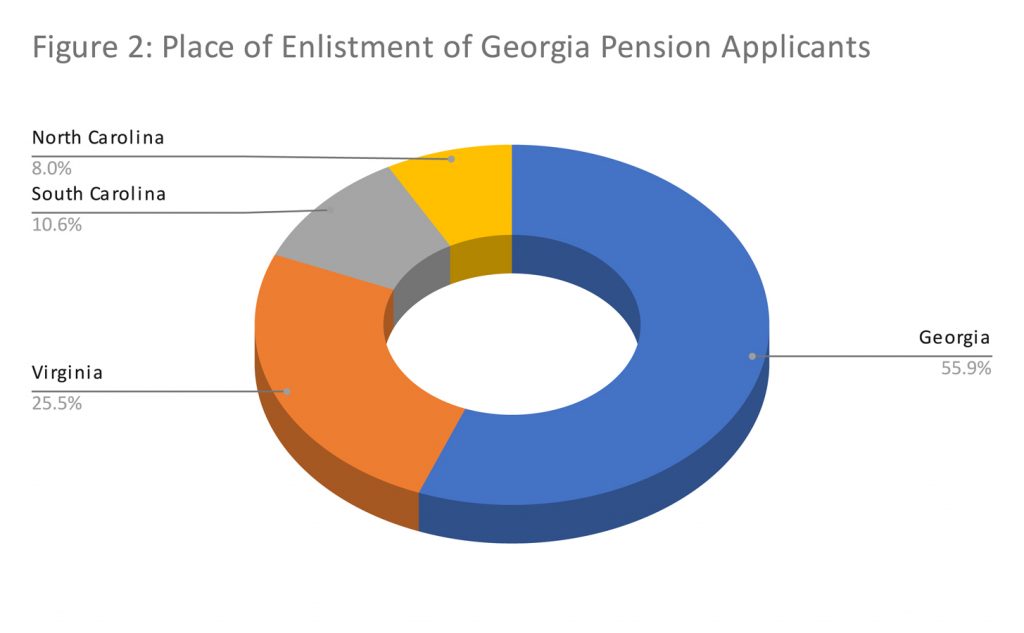

Only 56 percent of all Georgia pension applicants joined or enlisted in Georgia (Figure 2). In studying the men who joined or enlisted elsewhere (44 percent) it is abundantly clear almost all these men were not residents of Georgia before or during the war. Among Georgia Continental Line pension applicants, nearly 70 percent enlisted for Georgia service in other states. Men from Virginia figure most prominently among these men accounting for almost 50 percent of all Georgia Line pension applicants. North and South Carolina men account for another 20 percent of men in the Georgia Line. The Georgia militia had a much higher percentage of men who lived in Georgia. Over 84 percent of Georgia militia pension applicants entered service in one of the counties of the state. South Carolina accounts for over 13 percent of the men that entered the Georgia militia. North Carolina accounts for 3 percent of these men.

Comparing Georgia pension applicants’ places of enlistment to the North Carolina Line and militia yields stark differences. Only 1 percent of North Carolina Line applicants reported enlisting outside of North Carolina, a much lower percentage than the 70 percent of Georgia Continentals. Not one North Carolina militia pension applicant reported joining or volunteering from another state, a sharp contrast to the 16 percent of Georgia militia applicants.

Comparing Georgia pension applicants’ places of enlistment to the North Carolina Line and militia yields stark differences. Only 1 percent of North Carolina Line applicants reported enlisting outside of North Carolina, a much lower percentage than the 70 percent of Georgia Continentals. Not one North Carolina militia pension applicant reported joining or volunteering from another state, a sharp contrast to the 16 percent of Georgia militia applicants.

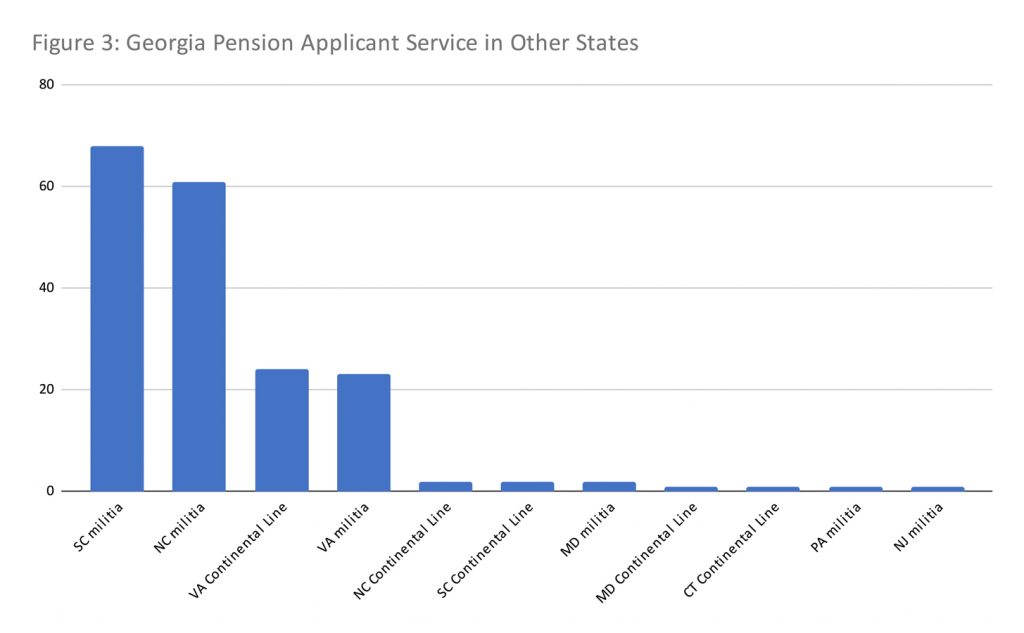

As a high number of Georgia pension applicants were from other states it stands to reason that a high number of men served considerable amounts of time in the units of other states. Over 45 percent of all men who served in a Georgia unit served a term in the service of another state. Overall these men served in seven states and eleven different military units (Figure 3). Four men each served in four different of these distinct units with one man serving in four states which include Georgia, North and South Carolina and Virginia.

LENGTH OF SERVICE AND NUMBER OF DEPLOYMENTS

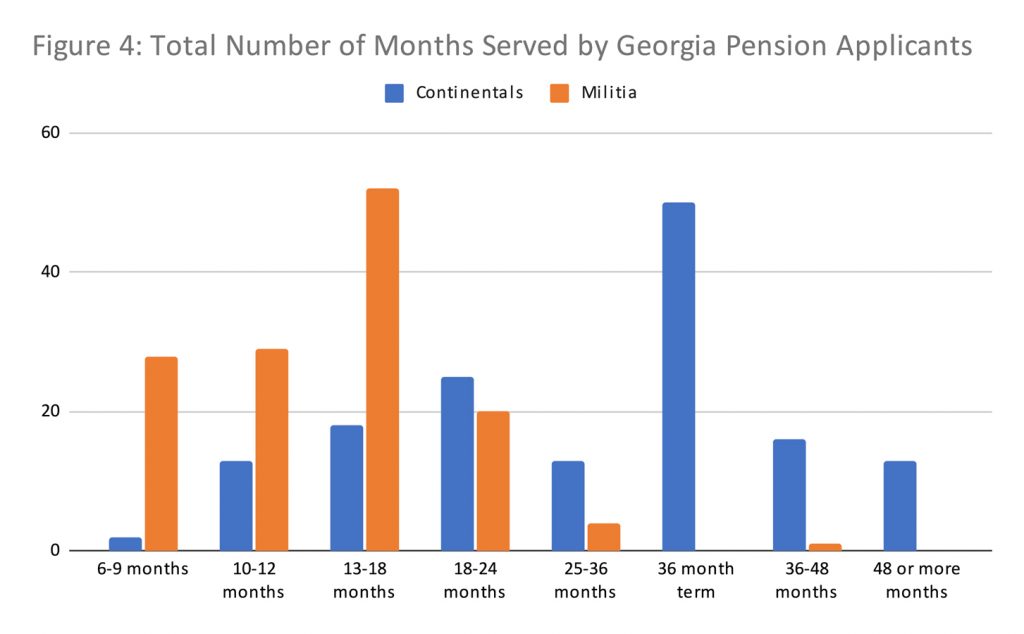

Overall, Georgia pension applicants averaged nearly twenty-three months in military service. The averages differ drastically between Georgia Continentals and men of the state’s militia. As with other states’ Continental regiments, Georgia Continental troops enlisted for longer periods of time (years) compared to militia (months). Forty-eight percent of Georgia’s Continentals enlisted for a term of three years with an average amount of time in service of thirty months. Comparatively, Georgia Continentals served longer than their North Carolina counterparts who averaged twenty-three months. Men who served in the Georgia militia served on average half the time of Continentals (fifteen months). This figure is considerably longer than North Carolina militia who served on average eleven months (Figure 4).

Georgia pension applicants served almost three tours of duty overall in their respective military units. Breaking down tours by branch, Georgia Continentals averaged two tours of duty while the militia served three terms. Fifty-eight percent of Continentals served two terms or more. Three Georgia Continentals served six total tours, each in various militia and Continental units across four states. Ninety-three percent of Georgia militia pension applicants served two or more terms with 37 percent serving four or more terms. Two militiamen served the most at seven terms and, interestingly, they only served in the Georgia and South Carolina militias (Figure 5).

Georgia pension applicants served almost three tours of duty overall in their respective military units. Breaking down tours by branch, Georgia Continentals averaged two tours of duty while the militia served three terms. Fifty-eight percent of Continentals served two terms or more. Three Georgia Continentals served six total tours, each in various militia and Continental units across four states. Ninety-three percent of Georgia militia pension applicants served two or more terms with 37 percent serving four or more terms. Two militiamen served the most at seven terms and, interestingly, they only served in the Georgia and South Carolina militias (Figure 5).

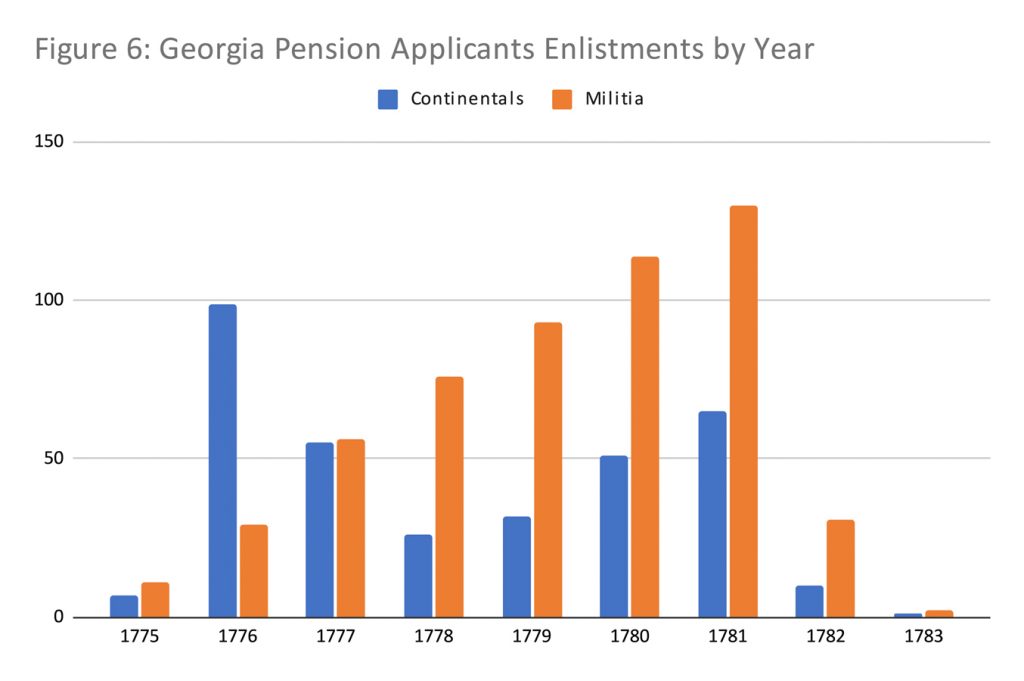

Georgia pension applicants’ enlistments by year reveal several differences between Continental and militia service. The height of Continental enlistments was early in the war (1776) and generally decreased from then onward. Conversely, militia participation began slowly and increased throughout the war coming to an apex in 1781 during the period when most of Georgia was retaken from British and Loyalist forces (Figure 6). The graph indicating this service should be considered in the broader context of pension service which includes a substantial proportion of men who served in other states. For instance, many men who served terms in the Georgia Line were discharged by 1779 and returned to their homes in the Carolinas and Virginia where they served again in the later years of the war. Thus the high number of militia enlistments in 1781 includes many men serving in Carolina and Virginia militias and participating in battles there. The same could be said for the rise in Continental Line numbers later in 1781.

Georgia pension applicants’ enlistments by year reveal several differences between Continental and militia service. The height of Continental enlistments was early in the war (1776) and generally decreased from then onward. Conversely, militia participation began slowly and increased throughout the war coming to an apex in 1781 during the period when most of Georgia was retaken from British and Loyalist forces (Figure 6). The graph indicating this service should be considered in the broader context of pension service which includes a substantial proportion of men who served in other states. For instance, many men who served terms in the Georgia Line were discharged by 1779 and returned to their homes in the Carolinas and Virginia where they served again in the later years of the war. Thus the high number of militia enlistments in 1781 includes many men serving in Carolina and Virginia militias and participating in battles there. The same could be said for the rise in Continental Line numbers later in 1781.

TERMS OF SERVICE

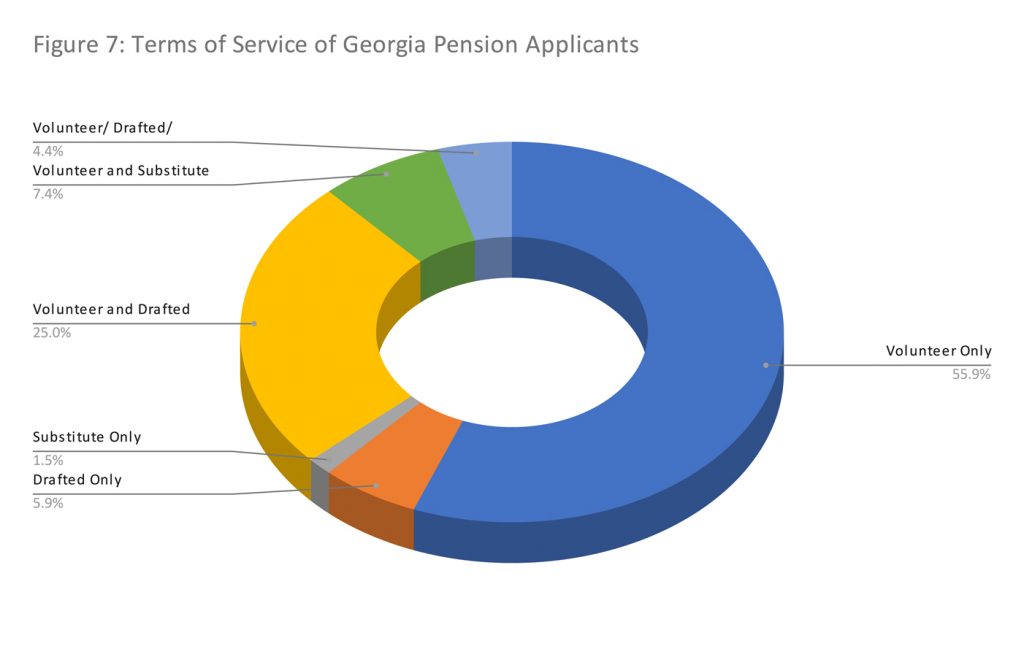

Almost all Georgia Continentals note “enlisting” in their respective regiments for set terms of service. The term “enlist” is most prevalent in Continental pension applications and is understood to be similar to how militiamen used the term “volunteer.” Whether these men were true volunteers or “drafted” for that service is not apparent in the pension applications. Much more variation is present in the terms of service of the Georgia militia who could enter service by volunteering, being drafted, or offering themselves as a substitute. An overwhelming majority (93 percent) volunteered for militia service at least once during the war. However, it is also true that 35 percent of all Georgia militia pension applicants were drafted at some point during the war (Figure 7).

One Georgia militiaman, Austin Dabney, appears to be the only man among Georgia applicants who was a substitute only. However, he may not have been a willing substitute as he was enslaved at the time of his entrance into the Georgia militia. Dabney served one term and was wounded at Kettle Creek in 1779. He was purchased by the state of Georgia in 1786 and subsequently emancipated. Interestingly, Dabney is one of only three Georgia men of color who can be identified from pension applications and other documentary sources.[13] Comparatively, Georgia appears to have had significantly lower rates (less than 1 percent) of free people of color in its service than North Carolina which had 2.5 percent of its militia pension applicants and 7 percent of its Continental applicants who were people of color. Two Virginia rolls (taken at the time of enlistment) roughly correspond with the North Carolina proportions of men of color. These rolls indicate a range of 5.8 percent to 9.5 percent of roughly 2,000 Virginia Continental Line soldiers who were men of color or of African descent.[14]

One Georgia militiaman, Austin Dabney, appears to be the only man among Georgia applicants who was a substitute only. However, he may not have been a willing substitute as he was enslaved at the time of his entrance into the Georgia militia. Dabney served one term and was wounded at Kettle Creek in 1779. He was purchased by the state of Georgia in 1786 and subsequently emancipated. Interestingly, Dabney is one of only three Georgia men of color who can be identified from pension applications and other documentary sources.[13] Comparatively, Georgia appears to have had significantly lower rates (less than 1 percent) of free people of color in its service than North Carolina which had 2.5 percent of its militia pension applicants and 7 percent of its Continental applicants who were people of color. Two Virginia rolls (taken at the time of enlistment) roughly correspond with the North Carolina proportions of men of color. These rolls indicate a range of 5.8 percent to 9.5 percent of roughly 2,000 Virginia Continental Line soldiers who were men of color or of African descent.[14]

BATTLES AND SKIRMISHES

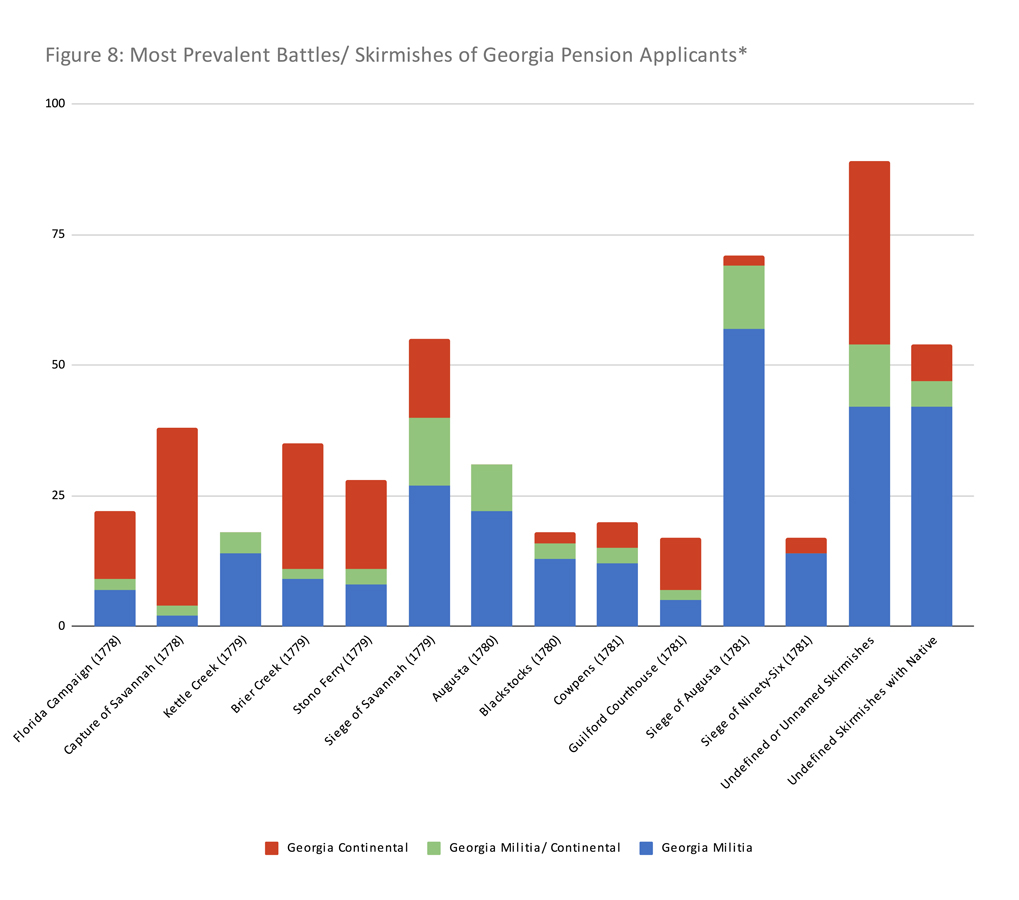

Georgia pension applicants were engaged in at least fifty-two different battles and/or skirmishes. However, this high number of actions is inflated by the 47 percent of applicants who served in other state’s militia or Continental Lines. Georgia pension applicants were not often clear about which military body they were in when they fought some battles. Also, for this study individual units and battles were not tracked. That said, twelve engagements stand out among the pension applicants. The battle mentioned by the most Georgia pension applicants was the Siege of Augusta in May and June 1781; included in this tabulation were the surrenders of nearby Forts Gaphin and Grierson. The other most prominent battle was the French/American Siege of Savannah in September and October 1779 (Figure 8).

A significant number of men served in what could be categorized as two types of unnamed skirmishes. Thirteen percent of all engagements reported by Georgia pension applicants are unnamed. Most of these were small-scale engagements between their units and Loyalist forces. A small proportion of the men described unnamed skirmishes with British forces around Savannah in late 1781 and 1782. About 8 percent of all the instances of battles and skirmishes were unidentified skirmishes with Native Americans on the frontiers of Georgia. Many of these engagements occurred (as described by the applicants) at frontier forts and outposts in the backcountry.

A significant number of men served in what could be categorized as two types of unnamed skirmishes. Thirteen percent of all engagements reported by Georgia pension applicants are unnamed. Most of these were small-scale engagements between their units and Loyalist forces. A small proportion of the men described unnamed skirmishes with British forces around Savannah in late 1781 and 1782. About 8 percent of all the instances of battles and skirmishes were unidentified skirmishes with Native Americans on the frontiers of Georgia. Many of these engagements occurred (as described by the applicants) at frontier forts and outposts in the backcountry.

The inclusion of one battle, Guilford Courthouse, at first glance may seem out of place as there were no known Georgia units present at that battle. Only one participant appears to have been in the Georgia militia at that battle. The rest were Georgia veterans who were serving in the Virginia Line, Virginia militia, or North Carolina militia. Clearly, these men served their term in the Georgia Line or militia only to serve again in units of their home state at that battle.

POSSESSIONS AND OCCUPATIONS

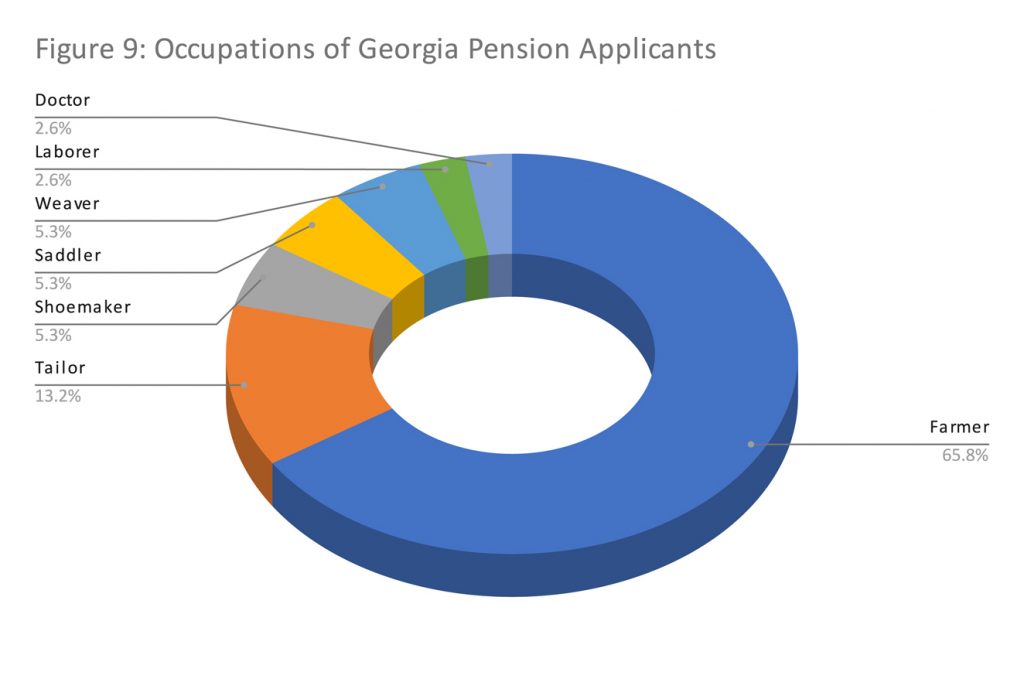

Approximately 10 percent of Georgia pension applicants (all of them Continental soldiers) provided a listing of their possessions or occupations. Only 18 percent of these Georgia pension applicants noted owning land at the time of their applications. This percentage is lower than the 25 percent noted by North Carolina applicants. The types and percentages of occupations are very similar to North Carolina pension applicants. Almost two-thirds (65 percent) of all the men were farmers. Other occupations include tailor, shoemaker, saddler, weaver, laborer, and doctor (Figure 9). About 11 percent of Georgia pension applicants reported owning enslaved people. This figure could be considered low given that 25 percent of households in 1860 owned enslaved people. However, this figure is higher than the individual rate of ownership (4.9 percent).[15] This figure for Georgia pension applicants is considerably higher than the 2.4 percent of North Carolina Continental pension applicants that reported owning enslaved people. A few possible reasons for this disparity may be the very small sample of Georgia applicants who reported their possessions or slave ownership and the much broader geographic residency of Georgia applicants from four states. Overall, among these two states the relatively low rates of slave ownership could plausibly be attributed to pensioners’ dire financial needs as demonstrated in their applications. Men (and families) who sought pension funds may not have owned enslaved people at time they applied for pensions.

LITERACY

Nearly 53 percent of Georgia pension applicants signed their pension applications. This percentage falls in between those of North Carolina Continental troops and militia which were at 47 percent and 53 percent respectively. All of these “literacy” rates are generally higher than the documented sources noted in the analysis of the North Carolina militia. It may be possible if not likely that some men could write their names legibly but not be able to read or write. These higher rates may also be somewhat inflated by the presence of officers in the pension applications who were more likely to be literate. Also, it is possible if not likely that some court officials signed the man’s name for him and no indication that this was done.

PRISONERS OF WAR

Over 26 percent of all Georgia pension applicants spent time as prisoners of war. Those men who served in the Georgia Continental Line were much more likely to have been taken prisoner (39 percent). Most of these men reported being captured during the surrender of Savannah, Fort Morris (Sunbury), Brier Creek, Stono Ferry, and the siege of Savannah. Just under half of all Georgia Continental prisoners reported escaping their captivity, some from prison ships. At least 11 percent of Georgia Continental prisoners reported joining the British army or navy while a prisoner. One man’s experience aboard a prison ship was not atypical. He was “exposed by a crowded prison and bad health [which] induced him to do so [take the British oath of allegiance]. Though he took the oath and at the same time intended to violate it, it was to escape from a prison of death.” The man soon escaped to Patriot-controlled Charleston where he received his discharge.[16]

About 14 percent of Georgia militia pension applicants were made prisoners of war. Forty-two percent of these men escaped their confinement. Militia prisoners of war had very different experiences than their Continental counterparts. Most militiamen appear to have been captured by Tories in the Georgia backcountry. One man was captured by Tories and turned over to local Native Americans who were ready to scalp him. The same Tories rescued the man and were in the process of hanging him when a “British” (most likely a Tory) officer saved him. After taking the oath of allegiance the man was paroled and eventually rejoined the Patriot militia.[17] Another Georgia militiamen taken prisoner was tortured by another “British” (likely another Tory) officer. He was hung by the neck three times until nearly dead to give up information on where the Tories could find hidden property. Eventually, he was taken down the Savannah River to the coastline where he was released.[18]

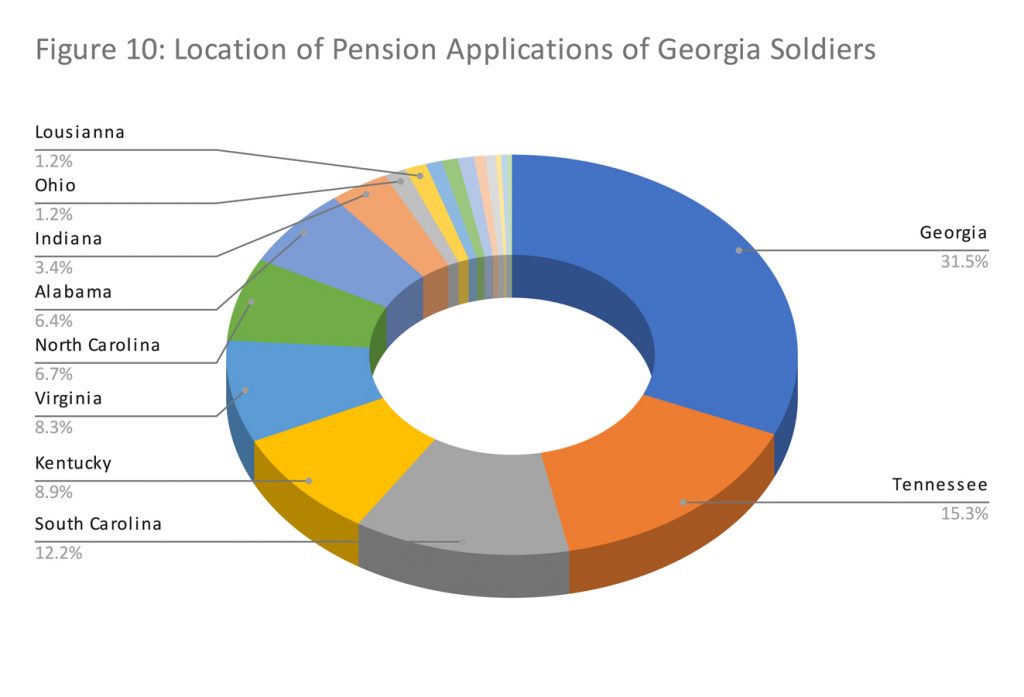

LOCATION OF PENSION APPLICATIONS

Georgia pension applicants (or their next of kin) filed applications from seventeen states after the war. Only 31 percent of these applications were filed in Georgia. Tennessee accounts for the next highest place of pension application filings at 15 percent followed by South Carolina at 12 percent. Other states include: Kentucky, North Carolina, Illinois, Virginia, Indiana, Missouri, Alabama, Ohio, Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida, Maryland, Iowa, and Arkansas (Figure 10). The high number of pension applicants who filed from other states seems to be influenced by where the men entered service. For instance, almost all of those who filed applications from Virginia were men who lived there before and during the war and enlisted in the Georgia Line. The same is true for North and South Carolina men who served in the Georgia Line or militia. Among men who joined the service in Georgia over 50 percent remained in Georgia until the time their pensions were filed. The proportion of men who joined or resided in Georgia follows the same lines as North Carolina Continental at nearly 50 percent who remained in the state but well above the 39 percent of militia that filed from other states.

CONCLUSION

The primary reason this study of Georgia soldiers was undertaken was that many questions arose from the two previous studies of North Carolina soldiers. Invariably, the question became: how might this data compare or contrast with the same data captured from other states? Were more men born in one state or another? Did the men of one state fight in more battles or serve longer? These were just a few of the questions. Perhaps the biggest realization (or even surprise) discovered in this study of Georgia was the degree to which men from Virginia and North Carolina served in and for the state of Georgia. A second realization was the high number of unnamed skirmishes that are so prevalent in Georgia applications. Clearly, a better understanding of the conflict in Georgia will be well served by more attention to these skirmishes. The third realization was the relatively high degree of pension applicants’ engagements with Native Americans beyond what might be considered the frontier. Anecdotally, most Georgia pension applicants seem to have had at least partial contact with enemy Native Americans or have worked at maintaining defensive posts against them. This, too, warrants more study.

When the first demographic study on the North Carolina militia was begun there were no plans to continue the work to other military bodies of other states, much less the North Carolina Line. Obviously, this sentiment has changed considerably with two additional studies. One might logically expect that the pension applications of South Carolina to be next in line, thus threading together the demographic data of three southern states. Fortunately, the pension applications of South Carolina are not nearly as numerous as those of North Carolina. The work in harvesting the data and writing South Carolina’s pension applicants collective story has already commenced.

The author would like to thank Will Graves and C. Leon Harris for their feedback and insights on Federal Pension Applications which form the basis of this work.

[1]All pension applications were sourced from Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Roster, revwarapps.org/. All applications used for Georgia pension applicants populating the data set were transcribed by Will Graves and C. Leon Harris.

[2]Population in the Colonial and Continental Periods, US Census Department.

[3]Fred Anderson Berg, Encyclopedia of Continental Army Units (Harrisburg, PA: Stackole, 1972), 45.

[4]Richard K. Wright Jr., The Continental Army (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 74.

[9]Lucian Lamar Knight, Georgia’s Roster of the Revolution (Atlanta, GA: Index Publishing, 1920), 7.

[11]Pension Application of Joel Darcy (S6788).

[12]Pension Application of Gilbert Tearney (W9850).

[13]The other two men were free men of color, not enslaved like Dabney.

[14]A Size Roll of Noncommissioned Officers and Privates of Virginia, revwarapps.org/b81.pdf; The Chesterfield Size Roll: Soldiers Who Entered the Continental Line of Virginia at Chesterfield Courthouse after 1 September 1780, revwarapps.org/b69.pdf

[15]Joseph T. Glatthaar, Soldiering in the Army of Northern Virginia: A Statistical Portrait of the Troops Who Served under Robert E. Lee (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011), Kindle Edition, 9.

[16]Pension Application of Henry Smith (W9300).

Recent Articles

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Those Deceitful Sages: Pope Pius VI, Rome, and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Thank you Eric! I should say that I have enjoyed your work...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...