American Patriots won a pivotal victory at Charlestown, South Carolina, on June 28, 1776, six days before the Declaration of Independence. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island was the Patriots’ first defeat of a joint attack by the British army and navy and one of their most decisive victories of the entire war. The astonishing win changed the course of the revolution as the British suspended their long-planned Southern strategy, allowing the South to remain relatively calm under Patriot control for the next three years.

Patriots had taken over the government of South Carolina and its wealthy capital Charlestown in 1775. In early June 1776, thousands of people in America’s fourth largest city witnessed a terrifying spectacle when an intimidating British force arrived offshore in more than fifty ships to begin restoring Crown rule. The expedition included a Royal Navy squadron with nine ships of war commanded by Commodore Sir Peter Parker and a British army commanded by Maj. Gen. Henry Clinton. Parker and Clinton sought a quick victory to show support for Loyalists and reestablish the Crown’s presence in the South before joining the British campaign to capture New York and isolate New England. They planned to secure Sullivan’s Island at the entrance to the busy harbor and leave two warships with a garrison of soldiers on the island to control the seaport until the British could return to reclaim all of Charlestown and South Carolina.[1] Commodore Parker and General Clinton developed a two-pronged strategy to capture Sullivan’s Island: the navy would bombard an unfinished fort of palmetto logs and sand, and the army would assault the fort’s vulnerable rear by land.

Responding to the threat posed by the British expedition, the Continental Congress appointed America’s most experienced senior military officer to command the Southern Department. Maj. Gen. Charles Lee was a brash, temperamental and demanding soldier of fortune who arrived at the same time as the British force and feverishly set about improving Charlestown’s defenses. Not knowing that the enemy’s objective was limited to Sullivan’s Island, he and the local Patriot leaders positioned troops in and around the city, with two of the colony’s most experienced officers at the points of the attack on Sullivan’s Island. Col. William Moultrie of the 2nd South Carolina Regiment commanded the fort, and Lt. Col. William Thomson of the 3rd South Carolina Regiment (Rangers) commanded troops guarding the island’s shoreline.

The Patriot soldiers stationed on Sullivan’s Island depended upon one another. If Thomson’s troops failed to stop the British army, Moultrie’s fort would surely fall to the simultaneous assaults from land and sea. If the fort could not withstand the Royal Navy, the Patriots defending the island would be trapped between the powerful forces of the British army and navy. The loss of Sullivan’s Island and some of the best soldiers in the Southern colonies would jeopardize the rebellion in Charlestown and South Carolina, with potentially dire consequences for the American Revolution.Fortunately for the Americans, the British attacks from land and sea were absolute failures.

Anxious eyewitnesses in the city were awestruck on June 28, 1776, as they watched Colonel Moultrie and his men heroically defend the fort on the horizon against a ferocious, day-long bombardment by the British warships. The fort’s thick walls of palmetto logs and sand stood firm while the Americans returned fire slowly and deliberately to conserve their precious supply of powder and ammunition. Their well-directed cannon fire killed or wounded more than 200 British sailors and inflicted debilitating damage to the warships, with modest American losses.[2] The valiant victory at the fort was extolled throughout the colonies and became the historical focal point of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island. It is commemorated today by the National Park Service at the iconic site later named Fort Moultrie.

As Patriots in the fort repelled the assault by sea, Colonel Thomson and a diverse band of Patriots repelled the British army’s attempt to assault the fort by land. They kept the British off Sullivan’s Island by blocking their crossing of an Atlantic Ocean inlet that separated Thomson’s force of 780 from Clinton’s army of 3,000. Thomson and his men were recognized for the victory and thanked by the Continental Congress.[3] However, their contribution was nearly lost in history like countless other remote battles of the revolution. The long and intricate battle of maneuvers and skirmishes was fought out of sight in the wilderness, witnessed by the participants only, and lacked the captivating drama of the fight at the fort. Few details were published, and the crucial victory eventually faded into obscurity. Through sources not readily available to early historians, we are learning how Colonel Thomson and his outnumbered, outgunned band maneuvered to the verge of victory before June 28 and thwarted the land attack on that fateful Friday.

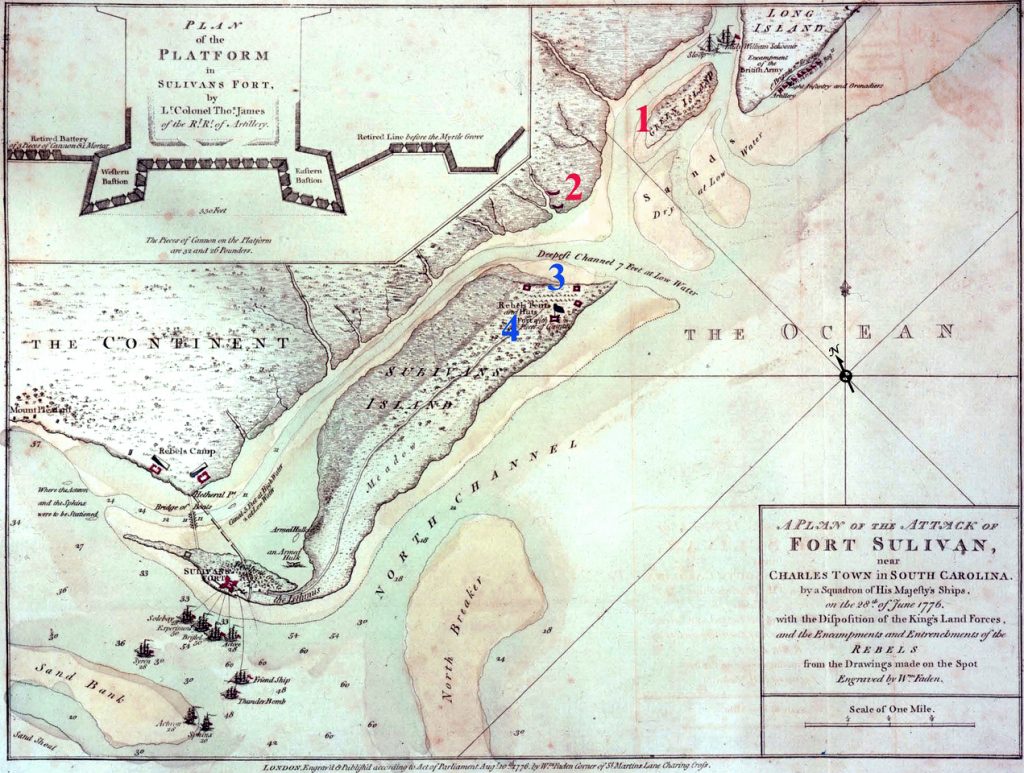

The British target, Sullivan’s Island, was a three-mile-long link in a chain of wild, sandy barrier islands separated from the mainland by marshes and creeks and separated from one another by ocean inlets.[4] The next link up the coast stretched eight miles to the northeast and was aptly named Long Island (now Isle of Palms). The inlet between Sullivan’s Island and Long Island, known as “the Breach” (now Breach Inlet),was a tidal flat more than a mile wide, laced with muddy bogs and sandbars that were exposed at low tide and gradually covered by surging ocean water as the tide rose twice per day. Constantly changing, shallow streams meandered among the sandbars and tidal pools, and a channel seven feet deep ran along the northern shore of Sullivan’s Island.[5]

A detachment of 210 rangers was defending the Sullivan’s Island shoreline when the British expedition anchored offshore and General Clinton scouted for ways to get his army onto the island to assault the fort.[6] Clinton and Parker initially planned a sudden attack, but the general did not want to land directly on Sullivan’s Island through rough surf under fire. Before verifying reports that the inlet separating Long Island from Sullivan’s Island was passable on foot at low water, he chose to stage his army on unoccupied Long Island and have the troops wade across the Breach to attack Sullivan’s Island on foot.[7]

British Force

Clinton and his two generals, Maj. Gen. Charles, Earl Cornwallis and Brig.Gen. John Vaughan, made unopposed landings in the middle of June at the northeast end of Long Island with all of their regular troops, Loyalists, and support personnel.[8] The army of 3,000 included the 15th, 28th, 33rd, 37th, 46th, 54th, and 57th Regiments of Foot; grenadier and light infantry companies of the 4th and 44th Regiments; the 1st Marines; the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Highland Emigrants; and companies of the 4th Battalion of the Royal Regiment of Artillery with cannon, howitzers, and mortars.[9] The army also had control of floating batteries, pilot boats, small armed craft, and three warships armed with at least twenty-two cannon. Schooners Lady William and Saint Lawrence were stationed in the creek flanking Long Island (now Hamlin Creek), and sloop Ranger was based in Spence’s Inlet (now Dewees Inlet) at that island’s northeast end.[10]

American Force

The Patriots facing the British army across the Breach were known as the “advance guard.” Their leader was a respected citizen-soldier from the South Carolina backcountry known by the sobriquet “Danger” for his bravery and daring in battle. Colonel Thomson had outfitted his 3rd South Carolina Regiment with distinctive caps displaying crescents that proclaimed, “Liberty or Death,”[11] a motto befitting the Battle of Sullivan’s Island. As the imposing British force was landing on Long Island, he assumed personal command of the advance guard and immediately requested reinforcements to offset his disadvantage in manpower and firepower. Patriot units were moved frantically to and from Sullivan’s Island until the advance guard totaled 780 soldiers. The diverse group included Thomson’s 3rd South Carolina Regiment of rangers, South Carolina state troops, North Carolina regulars, a small detachment of militia, a few artillerymen from the 4th South Carolina Regiment, and the Raccoon, or Foot Rover, company, which included approximately thirty warriors from the Catawba and associated American Indian tribes.[12] Thomson and some of his 3rd Regiment officers and men had combat experience, but most others were raw recruits hastily assembled to defend Charlestown. Their firepower was augmented with an 18-pound cannon and one or two 6-pound cannon in palmetto log fortifications overlooking the Breach between Long Island and Sullivan’s Island.[13]

After transferring his force from the ships to the northeast end of Long Island, Clinton and his officers spent nights “fording and reconnoitering those infernal bogs and creeks that lay contiguous to Sullivan’s Island.” He realized his false assumption about the depth of water in the Breach on June 18 and later wrote, “To our unspeakable mortification and disappointment we discovered that the passage across the channel which separates the two islands was nowhere shallower at low water than seven feet instead of eighteen inches, which was the depth reported.”[14] This deep channel made wading across the inlet impossible. The general should have investigated before committing his army to Long Island, and now he was in a self-inflicted predicament.

From his camp on Long Island, Major General Clinton sent Brigadier General Vaughan to the navy anchorage to tell Commodore Parker that the army could not ford the inlet to attack the fort as initially planned.[15] The British Secretary of State for the American Colonies had directed Clinton to avoid great loss and immediately proceed to New York if the mission could accomplish nothing of consequence,[16] but no record has been found that he considered abandoning the joint attack. As overall commander of the expedition, Clinton evaluated several alternatives and settled on an amphibious assault across the Breach to support the naval attack on the fort.

Amphibious Assault Tactics

Attacking with foot soldiers over water utilized special “flatboats” carried by the Royal Navy. These versatile boats rowed by sailors were well-suited to crossing the Breach. They were more than thirty feet long and floated in just two feet of water. Each flatboat could transport up to six tons of equipment or fifty soldiers, and they could be outfitted with sails and swivel guns (small cannon). The British expedition had fifteen functioning flatboats, enough to land several hundred men in a wave before the sailors rowed back across the inlet for another wave.[17] The soldiers packed tightly in the center of the open boats with their muskets held upright could not fire. They would disembark as fast as possible to establish a beachhead while British artillery or warships disrupted the enemy defenses with suppressing fire.[18] Thomson’s troops on Sullivan’s Island were more than a mile from the British artillery on Long Island, too far for effective suppressing fire. To support the amphibious crossing, Clinton needed to find high and dry ground closer to Sullivan’s Island for artillery batteries or deep and wide channels inside the Breach for warships.

Adverse Conditions

While the opposing forces searched for advantageous positions in and around the Breach, more than 4,000 British and American people on the two islands endured miserable conditions. Summer on South Carolina’s sunbaked barrier islands was nearly unbearable for anyone, especially for those from cooler climates who had suffered grueling voyages, illnesses, and food shortages. A surgeon who sailed from England with the expedition wrote of the suffocating heat with “Not a breath of air stiring—thick cobwebs to push thro’ everywhere, knee deep in rotten wood and dryed Leaves, every hundred yards a swamp with putrid standing water in the middle, full of small Alligators . . . and no place intirely free from Rattle Snakes.”[19] A young British captain told his family about living “like beasts of the field” and “lying five nights in the midst of a putrid marsh up to the ankles in filth and water.”[20] A soldier encamped in the Long Island wilderness wrote to his brother,

We have lived upon nothing but salt Pork and Pease. We sleep upon the Sea Shore, nothing to shelter us from the rains but our coats and a miserable paltry blanket. There is nothing that grows upon the island, it being a mere sand-bank, and a few bushes that harbour Millions of Musketoes, a greater plague than there can be in Hell itself. . . . The oldest of our officers do not remember, of ever undergoing such hardships, as we have done since our arrival here.[21]

Ten Days of Maneuvers and Skirmishes

Combat quickly made discomfort a secondary concern. An American rifleman shot a member of a British scouting party on Long Island early in the conflict. According to a Patriot, “He was dressed in red, faced with black, and had a cockade & feather in his hat and a sword by his side. By which it appears that he was an officer.”[22] The action escalated when most of the British army marched to the southwest end of Long Island and set up camp directly across the inlet in view of the Patriot advance guard. The opposing forces remained on duty day and night, as sentinels and patrols approached dangerously close to their enemies across the marshes and creeks on the west side of the Breach.[23] A British diarist noted on June 20, “One of ours was shot thro’ the leg last night, and Captain Trail shot one of their Officers thro’ the head this morning, I saw him fall immediately and never stired afterwards.”[24]

Inexperienced Patriots incurred the wrath of General Lee by firing ineffectively from extreme distances and passing over to Long Island without orders.[25] Seeking a reward for the first prisoner captured, three Patriots paddled to a British camp at night, failed to take a prisoner, and mistakenly shot a member of their own party. The British tracked the group back to the Breach, where the advance guard opened fire, igniting hours of intense combat with casualties.[26] This action was so loud and long-lasting that Commodore Parker, anchored five miles south, thought the main battle had begun at the Breach and ordered his ships to create a diversion.[27]

On another day, Loyalist Scots Highlanders shouted in Gaelic as they attacked Patriots on a sandbar and ambushed a group of the Catawba on the Sullivan’s Island beach. They shot with impressive accuracy until dislodged by grape and other shots from American artillery.[28] Thomson’s cannon fired on the armed schooner Lady William, an armed sloop, and a pilot boat in the creek beside Long Island, hitting the ships several times before they could retreat up the creek and out of range.[29] The frequent, long-distance exchanges of artillery and small arms fire caused minimal equipment damage and casualties while revealing the abilities and limitations of both forces.[30] After ten days of combat at the Breach,[31] General Lee ordered 100 more troops to ease the burden on Thomson[32] and sent thanks to his regiment for the “cheerfulness and alacrity for which they have done very hard duty.”[33]

British Advantage

A successful amphibious attack became plausible when the British army on Long Island discovered and occupied high ground on marsh islands significantly closer to Sullivan’s Island. Portions of Green Island (1 on the map above) could support infantry and long-range artillery approximately one mile from Sullivan’s Island.[34] High oyster banks on a small island at the west end of the Breach could serve as natural breastworks (2) within a half-mile of Thomson’s shoreline defenses (3).[35] The British gained a tactical advantage by emplacing two howitzers, two Royal mortars, and two 6-pound cannon behind an oyster bank breastwork and firing exploding shells into the advance guard’s positions. The gunfire disabled an American 6-pound cannon and caused casualties, proving that the artillery was close enough to suppress the American defenses during an amphibious crossing of the Breach.[36] A Patriot major was sure the British artillery would “cover their landing in spite of all we can do,” and said every officer in the advance guard considered the situation desperate and expected to be sacrificed, although they would “not quit the island were they certain of death.”[37] Encouraged,General Clinton and Commodore Parker arranged to launch simultaneous attacks the next day if the winds were favorable for the naval attack on the fort. Parker closed a dispatch to Clinton with confidence: “I trust, that I shall to Morrow Evening have the Honor of taking You by the Hand on Sullivan’s Island, and congratulating You on the Success of His Majesty’s Arms by Land and Sea.”[38]

Momentum Shift

Commanding from the mainland,Maj. Gen. Charles Lee gave Moultrie and Thomson scathing critiques about maintaining discipline and firing only within prescribed ranges. He added this postscript to a dispatch: “PS: Those two field pieces at the very end of the point [3], are so exposed that I desire you will draw them off to a more secure distance from the enemy; in their present situation, it appears to me, they may be carried off whenever the enemy think proper.”[39] Danger Thomson immediately established new positions that not only diminished the British artillery threat, but also gave the Americans a critical advantage. He moved his soldiers and cannon away from the Breach to a new location (4),[40] further outside the effective range of British heavy artillery on Green Island and barely inside the range of British light artillery behind the high oyster banks. From this less vulnerable position, Thomson’s cannon remained close enough to fire on unprotected British troops in flatboats before they could land on the Sullivan’s Island beach. General Clinton described the momentum shift:

The Rebels had time to perfect another Battery and Intrenchment that was begun on the 22d. This being 500 yards back from their first Position on the Point, in very strong Ground with a much more extended front, having a Battery on the right and a Morass on the left, & abattis in front, obligd us to make an entire Change in the Plan of operations on our Side. For it was apparent, that the few men I had Boats for, advancing singly through a narrow channel uncovered & unprotected, could not now attempt a landing without a manifest Sacrifice.[41]

Prompted by Lee’s postscript, Danger Thomson and his men had outmaneuvered the British army. General Clinton was dejected after the Americans’ rapid change to the new position, which he described as“defended and sustained by 3 to 4000 men [with] a formidable appearance.”[42] Actually, the advance guard was only one-fourth that size.

Blocked at the Breach

Clinton had few options for his army following Thomson’s move, and he may have lost resolve after ten days of planning, skirmishing, and maneuvering. Realizing the hazards of attacking across the well-defended Breach, he offered troops to assist the navy at the fort, which Sir Peter Parker did not accept. He also considered attacking Haddrell’s Point at Mount Pleasant on the mainland (Hetheral Pt on the map). This impractical and dangerous alternative diverged from the mission of occupying Sullivan’s Island, and it entailed more problems than attacking across the Breach. The British explored the creeks and two-mile wide marsh between Long Island and the mainland and Clinton asked Parker to provide naval support for an attack or diversion toward Mount Pleasant. Parker planned to enfilade the fort with three ships, which he suggested might be useful if the army attacked the mainland.[43] In his final dispatch before the main battle began, the beleaguered general told his naval counterpart that his situation was “rendered more difficult every hour, from the preparations the Rebels are making to defend themselves . . . every where intrenching themselves in the strongest manner.” With no firm plan for attacking the strengthened American defense, he told Parker, “It is impossible for me at this time and under my Particular Situation to enter upon a detail of the operations of the Troops on the day of your attack, they will in all probability depend upon different circumstances, subject to a variety of changes as occasion may arise.”He reiterated his ambiguous promise that “the Troops under my command will cooperate with you to the utmost for the good of His Majestys Service as soon as Wind and Weather shall favor the attack of the Fleet.”[44] The outnumbered and outgunned Americans had neutralized the British army, and they were on the verge of victory when conditions favored the British naval attack.

June 28, 1776

Col. William Moultrie and Lt. Col. William Thomson were together at the Breach on Friday morning, June 28, when they saw the British flatboats and warships spring into action. Moultrie galloped back to the fort and led his men to a resounding victory over the Royal Navy in a vicious battle.[45] Contemporary descriptions of the long day’s action at the Breach varied from an innocuous demonstration reported by Clinton to deadly fire reported by others. Some accounts may have been exaggerated, but all agreed that the strong American defense thwarted the land attack and made possible the astounding victory on Sullivan’s Island.

The battle began mid-morning when the Royal Navy opened fire on the fort and the British army opened fire on the advance guard. One of Lord Cornwallis’s brigades crossed a creek in flatboats and moved to the marsh island where the British light artillery battery fired from behind a high oyster bank breastwork (2). From a flatboat, Cornwallis’ surgeon saw a large British Coehorn mortar initiate the attack by throwing nine-inch shells into the Patriot trenches and artillery positions. He watched the howitzers, mortars, and cannon raining fire on the American defenses from the oyster bank, and he saw the Americans returning fire with musket balls and grapeshot from the 18-pounder “supplied entirely by slaves.”[46]

Attempted Amphibious Crossings

Tides governed actions in the battle at the Breach. After firing artillery to disrupt the American defenders, the British launched the amphibious operation as the predictable tide was rising several feet from its low point at about 10:30 a.m. to its high point at about 5:00 p.m.[47] Charles Stedman, a respected British officer and historian who served with Clinton and Cornwallis, summarized the first crossing attempt: “At twelve o’clock the light-infantry, grenadiers, and the fifteenth regiment, embarked in boats, the floating batteries and armed craft getting under way at the same time to cover their landing on Sullivan’s Island.”[48] Shallow water and Patriot artillery foiled support from the British warships. Clinton reported, “While the sands were uncovered [i.e., when the tide was still low], I ordered small armed vessels to proceed towards the point of Sulivan’s Island but they all got aground.”[49] One of his senior aides observed, “The foremost of the Vessels suffered considerably” from Thomson’s 18-pounder,[50] and aLoyalist aboard the British armed schooner Lady William reportedly said that it was impossible to withstand the destructive fire the Americans poured in.[51] The flatboat flotilla abandoned the crossing under fire. Stedman wrote, “Scarcely, however, had the detachment proceeded from Long Island, before they were ordered to disembark and return to their encampment: And it must be confessed that, if they had landed, they would have had to struggle with difficulties almost insurmountable.”[52] An American stated, “One Brigade had either embarked in their flat bottom boats or were about it, when theyReceived such a fire from our troops as made them think it would be out of their power to get Thomson’s consent to land, without which their Army would have pretty well melted down, by the time they would have got to the Fort.”[53] A Patriot leader wrote that the British “Land Forces on Long Island in the meantime strained every Nerve to effect a Landing on the Back [of Sullivan’s Island], but the Eighteen Pounder with Grape shot spread Havock, Devastation, and Death, and always made them retire faster than they advanced.”[54] Awed by the American cannon loaded with grapeshot, a British soldier wrote to his family, “They would have killed half of us before we could make our landing good.”[55]

Further amphibious crossing attempts would have been futile. After low tide and Patriot cannon fire turned back the warships and flatboats, the rising tide forced the British to evacuate their indispensable artillery battery at the high oyster banks. Notes in Clinton’s papers say,“As the Tide rose very fast it was reported to the General that the Artillery could stay no longer with safety . . . as therefore there was no one single thing that could go down to cover our landing, till such protection could be obtained, it was thought by all rash to attempt it.”[56] With the enemy’s warships and most effective artillery out of action, Thomson could more safely move soldiers and cannon from his second line of defense (4) back to his initial positions at the shore (3) and fire directly at British troops attempting to cross the Breach. Unprotected soldiers and sailors in slow-moving flatboats had little chance of establishing a beachhead through a point-blank barrage of bullets, balls, or grapeshot.

Major General Lee reinforced the advance guard with hundreds of fresh troops from Virginia and South Carolina after 5:00 p.m.[57] The well-armed British continued firing long-distance artillery across the inlet until nightfall, and the Americans nearly exhausted their supply of ammunition and gunpowder. When firing stopped, they reserved enough powder for only two shots from each cannon.[58] Frustrated and unaware of the severe beating sustained by the Royal Navy at the fort, General Clinton met with his officers that night and decided to make another crossing attempt the following morning despite the risk.[59] After eighteen hours under arms in the marsh, Lord Cornwallis’ troops were reloaded into the flatboats and started across the Breach at daybreak on June 29. When Clinton learned that the naval assault had failed and the battle was lost, the attack orders were countermanded and the British regulars in the flatboats returned to shore.[60] For the first time, the revolutionary Americans had defeated a joint attack by the British army and Royal Navy.

International News

The victory on Sullivan’s Island brought hope to the American cause. The stunning news appeared in dispatches, letters, and the same American and European publications as the Declaration of Independence and the massive campaign for New York. King George III, who had personally approved the expedition eight months prior, expressed his dismay with classic British understatement: “Though the attack upon Charles Town has not been crowned with success, it has by no means proved dishonorable; perhaps I should have been as well pleased if it had not been attempted.”[61] Clinton and Parker argued after the battle and alluded to each other’s deficiencies in their carefully crafted accounts.[62] Clinton depicted his army’s fire and movement as a demonstration or diversion and did not comment on the skirmishes, casualties, or attempted crossings.[63] He was highly offended by Parker’s official report to the British Admiralty in London, which stated, “Their Lordships will plainly see by this Account, that if the Troops cou’d have co-operated on this Attack, that His Majesty wou’d have been in possession of Sulivan’s Island.”[64] According to The Annual Register, a contemporary summary of 1776 British history, “During this long, hot, and obstinate conflict, the seamen looked frequently and impatiently to the eastward, still expecting to see the land forces advance from Long Island, drive the rebels from their intrenchment, and march up to second the attack on the fort. In these hopes they were grievously disappointed.”[65] The epic failure in his first major command would haunt Henry Clinton for the rest of his life, leading the editor of his memoirs to wryly observe, “Britain had worse defeats in the course of the war, but no more egregious fiasco.”[66]

Unsung Heroes

Lt. Col. William Thomson’s advance guard won the battle at the Breach and assisted in the grand victory on Sullivan’s Island with brave conduct by people from all echelons of society—Black men and American Indians as well as White farmers and workers from the backcountry of South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia. Like countless others in forgotten fights, the hastily assembled soldiers were not schooled in the art of warfare, and they made mistakes, yet they overcame adversity to prevail against enormous odds. The Americans strengthened their positions during British delays, adapted smartly to enemy maneuvers, seized the initiative by relocating their defenses, gained valuable skills and confidence over ten days of combat, and took advantage of the terrain and tides on June 28. Danger Thomson and his diverse band of unsung heroes were instrumental inwinning one of the earliest, most complete, and most shocking victories of the American Revolution.

[1]Narrative of Major General Henry Clinton in William James Morgan, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution,vol. 5, American Theatre: May 9, 1776 – Jul. 31, 1776 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1970), 325-327; Peter Parker to Henry Clinton, June 2, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents,351; Clinton to Lord George Germain, July 8, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 982.

[2]Account of the Attack made upon Sullivan’s Island by William Chambers, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 804; Parker to Philip Stephens, July 9, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 1001; William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, vol.1 (New York: David Longworth, 1802), 177.

[3]Journal of the Continental Congress, July 20, 1776, in American Archives 1837-1853 (Washington, DC: M. St Clair Clarke and Peter Force), 1585.

[4]Edward McCrady, LLD, The History of South Carolina in the Revolution 1775–1780 (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1902), 135-36; William Faden, A Plan of the Attack of Fort Sulivan (London: Charing Cross, 1776); John Campbell, Plan of the scene of action at Charlestown in the province of South Carolina the 28th June 1776 (Ann Arbor: William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan), quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/i/image/image-idx?id=S-WCL1IC-X-864%5DWCL000958; John Campbell, Charlestown and the British attack of June 1776 (Ann Arbor: William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan). The Faden map is the annotated map for this article; the Campbell maps were General Clinton’s battle maps.

[5]The inlet has changed significantly since the revolution, which can confuse those referring to maps drawn more recently. Map comparisons show that accreting sand filled much of the underwater terrain in the nineteenth century, reducing the distance between Long Island and Sullivan’s Island from more than a mile in 1776 to the present one-fourth of a mile.

[6]Samuel Wise to Henry William Harrington, June 7, 1776, in Alexander Gregg, History of the Old Cheraws (Columbia, SC: The State Company, 1905), 268.

[7]William B. Willcox, ed., The American Rebellion: Sir Henry Clinton’s Narrative of His Campaigns, 1775-1782,vol. 1 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954), 30-31; Henry Clinton to Lord George Germain, July 8, 1776, in K. G. Davies, ed., Documents of the American Revolution 1770-1783, vol. XII (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, Ltd., 1976), 163.

[8]Clinton Narrative, June 7 to 16, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 573.

[9]Robert Beatson, LLD, Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain from 1727 to 1783, vol. 6 (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1804), 45; Chambers Account in Morgan, Naval Documents,804.

[10]Parker to Stephens, July 9, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 998.

[11]Michael Scoggins,“Here Come the Liberty Caps!” A History of the Third South Carolina Regiment (York, SC: Culture & Heritage Museums, 2006, 2007, and 2008), 2-3; Morgan Brown, “Reminiscences of the Revolution,” Russell’s Magazine, vol. 6, October-March 1860 (Charleston, SC: Walker, Evans & Co), 62.

[12]Moultrie, Memoirs, 142; John Drayton, LLD, Memoirs of the American Revolution: From Its Commencement to the Year 1776, Inclusive, vol. II (Charleston: A. E. Miller, 1821), 288-289; McCrady,History in the Revolution, 145. The Catawba tribe allied with the South Carolina Patriots, who often used the term “Catawba” for any Indian warriors who fought by their side.

[13]Moultrie,Memoirs, 142; Joseph Johnson, MD, Traditions and Reminiscences, Chiefly of the American Revolution in the South (Charleston, South Carolina: Walker and James, 1851), 94.

[14]Willcox, American Rebellion, 1:30-31, 374-75.

[15]Clinton to John Vaughan, June 18, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 609. The British army and navy commanders were based miles apart and communicated indirectly and often ineffectually through dispatches and intermediaries, partly because Clinton was prone to seasickness and declined to stay aboard Parker’s flagship.

[16]Clinton Narrative, April 18 to May 31, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 327.

[17]Capacity estimates varied from 400 to 700 per wave per sources in Morgan, Naval Documents, 608, 653, 782, and 783; Francis, Lord Rawdon to the Earl of Huntington, July 3, 1776, in Hastings Family Papers (San Marino, CA: The Huntington Library), mssHA, Box 99, HA 5116.Lord Rawdon, an officer on Clinton’s staff, estimated that the flatboats would need at least one-half hour to transport each wave of troops.

[18]Hugh T. Harrington, “Invading America: The Flatboats That Landed Thousands of British Troops on American Beaches,” Journal of the American Revolution (March 16, 2015): March 5, 2023. Two months after the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, General Clinton successfully employed these tactics in the Battle of Long Island, New York, where the terrain and situation were favorable and the landing was unopposed.

[19]Thompson Forster, Diary of Thompson Forster, Staff Surgeon to His Majesty’s Detached Hospital in North America, October 19th 1775 to October 23rd 1777, June 16, 1776, unpublished typescript, 63.

[20]James Murray to Bessy, July 7, 1776, in Eric Robson, Letters from America, 1773 to 1780 (New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc., 1950), 29-30.

[21]Will Falconer to Anthony Falconer, July 13, 1776, in The South Carolina and American General Gazette, August 2, 1776, in R. W. Gibbes, ed.,Documentary History of the American Revolution, 1776-1782(New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1857), 19-21.

[22]Richard Hutson to Isaac Hayne, June 24, 1776, in Richard Hutson Letter Book 1765-1777(Charleston, SC: The South Carolina Historical Society), 34/559.

[23]Wise to Harrington, June 27, 1776, in Gregg, Old Cheraws, 271.

[24]Forster, Diary, June 20, 1776, 66.

[25]Charles Lee to William Thomson, June 21, 1776, in The Lee Papers, vol. 2, 1776-1778(New York: Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1872), 76-77.

[26]Hutson to Hayne, June 24, 1776, in Hutson, Letter Book. A wound likely sustained in this engagement is mentioned in a pension application transcribed by Will Graves, revwarapps.org/w8668.pdf.

[27]Parker to Stephens, July 9, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents,998.

[28]Wise to Harrington, June 22 and 27, 1776, in Gregg, Old Cheraws, 268-273. The Royal Highland Emigrants probably included Scots from the Cross Creek (now Fayetteville) area of North Carolina who joined the expedition at Cape Fear following their defeat by the Patriots at Moore’s Creek Bridge on February 27, 1776.

[29]A British Journal of the Expedition to Charleston, South Carolina, June 25, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 747. The creek is known today as Hamlin Creek. Gazette, August 2, 1776, in Gibbes, Documentary History 1776-1782, 15.

[30]Wise to Harrington, June 27, 1776, in Gregg, Old Cheraws, 271-272;Hutson to Hayne, June 24, 1776, in Hutson, Letter Book; Forster, Diary, June 21-22, 1776, 67-68; Brown, “Reminiscences,” 64-65. The large numbers of enemy killed and wounded estimated by British surgeon Forster and American sergeant Brown appear exaggerated and are not corroborated by other sources.

[31]Wise to Harrington, June 27, 1776, in Gregg, Old Cheraws, 271-272.

[33]Charles Lee to John Armstrong, June 27, 1776, in Lee, Papers, 89.

[34]Green Island, also called Willow or South Island, remains uninhabited and is now known as Little Goat Island.

[35]Faden, Plan of Attack; Campbell, Plan of the scene;Campbell, Charlestown and the British attack. Two symbols for batteries behind the breastworks appear on the Faden companion map and General Clinton’s battle maps by John Campbell. Notes on the Campbell maps indicate that the artillery retired to the northern oyster bank when the southern bank overflowed. This hummock, now known as Clubhouse Point, lies between Inlet Creek and Swinton Creek, 350 yards north of the modern bridge connecting Sullivan’s Island and Isle of Palms.

[36]Forster, Diary,June 22, 1776, 68. The advance guard positions 700-1,000 yards away were within the maximum range of these British artillery pieces. Cannon of the era could fire iron balls more than 1,000 yards, Royal mortars fired exploding shells up to 1,000 yards, and howitzers fired balls or shells up to 700 yards. The most effective fire was from less than half these ranges, depending upon powder quality, winds, humidity, crew skills, incoming fire, and other factors.

[37]Wise to Harrington, June 22, 1776, in Gregg, Old Cheraws, 269.

[38]Parker to Clinton, June 22, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 689. The winds were not favorable for an attack on June 23.

[39]Lee to William Moultrie, June 21, 1776, in Lee, Papers, 79; Moultrie, Memoirs, 158-162. Messages from the mainland to Thomson frequently were sent through Moultrie, who was stationed at the fort between the mainland and the Breach with overall responsibility for the defense of Sullivan’s Island.

[40]Faden, Plan of Attack; Campbell, Plan of the scene; Campbell, Charlestown and the British attack. The Patriots’ first and second lines of defense appear on all three maps. The second line extended across Sullivan’s Island near modern-day Stations 29 and 30.

[41]Willcox, American Rebellion, 1:32; Clinton to Germain from camp on Long Island, July 8, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 983-984. Germain was the British secretary responsible for the American colonies.

[42]Clinton to Germain, July 8, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 984. Thomson’s defenses may have deceived the general, or Clinton may have overstated enemy strength to excuse his failure to capture Sullivan’s Island.

[43]Parker to Clinton, June 25, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 745. These ships ran aground on June 28 and Clinton did not attack the mainland.

[44]Clinton to Parker, June 26, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents,760-61.

[46]Forster, Diary, June 28, 1776, 69-70. Forster’s meaning is unclear because the term “slaves” was used for common soldiers as well as enslaved people. African Americans in the advance guard included a drummer mentioned in Wise to Harrington, June 27, 1776, in Gregg, Old Cheraws, 272-273, and a soldier granted a federal pension for the service described in his pension application transcribed by Leon Harris,revwarapps.org/w11223.pdf

[47]C. Leon Harris, An Estimate of Tides During the Battle of Sullivan’s Island SC, 28 June 1776, 2010, thomsonpark.org. Other sources predict tides within minutes of Harris’s timeframe.

[48]Charles Stedman, The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War, vol. 1 (London: J. Murray, J. Debrett, J. Kerby, 1794), 186.

[49]Clinton to Germain, July 8, 1776, in Davies, American Revolution, 164; Moultrie,Memoirs, 174. The incoming tide would have deepened the inlet channels in favor of the British vessels, although the strongest currents would have made rowing and sailing most challenging during the middle of the tide cycle in the afternoon.

[50]Rawdon to Huntington, July 3, 1776, in Hastings Family Papers.

[53]William Bull to John Pringle, 13 August 1776, in Anne King Gregorie, ed., The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, vol. L, 1949 (Charleston, SC: The South Carolina Historical Society), 148.

[54]Richard Hutson to Thomas Hutson, June 30, 1776, in Hutson, Letter Book.

[55]Will Falconer to Anthony Falconer, July 13, 1776, in Gibbes, Documentary History 1776-1782, 20.

[56]Particulars Relative to the Attack [on Sullivan’s Island], June 29, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 827-828.

[57]Lee to Moultrie, June 28, 1776, in Lee,Papers,91-92; Drayton, Memoirs,296. Col. Peter Muhlenburg and his 8th Virginia Regiment had marched to Charlestown with General Lee and were stationed at Haddrell’s Point.

[58]Manuscript of William Henry Drayton, June 28, 1776, in Gibbes, Documentary History 1776-1782, 10.

[59]Willcox, American Rebellion, 1:35; Particulars, June 29, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 827–28. The high tide that coincided with sunrise on June 29 provided deeper water for warships and flatboats, while precluding artillery support from the oyster banks.

[60]Forster, Diary, June 29, 1776, 72-73; Particulars, June 29, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 827–28; Lee to George Washington, July 1, 1776, in Lee, Papers,102. The action on June 29 accounts for the second crossing attempt mentioned in several reports of the action at the Breach. Reports of three or more attempts are not well-documented.

[61]King George III to John Montagu, August 21, 1776, in B.R. Barnes and J.H. Owen, eds., The Private Papers of John, Earl of Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty, 1771-1782, vol. 4 (London: Navy Records Society, 1932-1938), 44.

[62]Washington to John Hancock, August 7, 1776, in Founders Online,National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0453. Deserters from the British warship Solebay told General Washington in New York, “That the Admiral turn’d Genl Clinton out of his Ship after the Engagement with a great deal of abuse—Great Differences between the principal naval and military Gentlemen.”

[63]Clinton to Germain, July 8, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 984. Clinton reported that his troops were positioned to attempt a landing on either Sullivan’s Island or the mainland.He knew that three Royal Navy frigates ran aground while attempting to enfilade the fort and did not send troops toward the mainland.

[64]Parker to Stephens, July 9, 1776, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 999-1001.

[65]The Annual Register or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature For the Year 1776 (London: J. Dodsley, 1779), 160-163. This reference work was widely read on both sides of the Atlantic.

[66]Willcox, American Rebellion, xxi. General Clinton learned from the experience. He returned and captured Charlestown with a highly successful siege in 1780.

2 Comments

Wonderful to see that your research has led to long overdue recognition of this battle with the Thomson Park. I grew up in the area in the late 60s and 70s. Much time was spent boating and fishing around Breach Inlet. While familiar with the greater details of the Battle of Sulliva’s Island, I had no clue regarding events in this area. My Roomate from The Citadel lived on the north side of the inlet. Can’t imagine 3,000 troops attempting a crossing. It was always a perilous place for swimmers.

Outstanding work on this. The narrative on the Breach Inlet has never really made sense, and now it does. That’s a big deal. I don’t know Doug McIntyre, but I know he has spent many years studying this subject–and it shows. Great work.