For Sir Henry Clinton, the capitulation of Charleston, South Carolina constituted not only the most stunning British victory of the war, but something of a personal vindication as well. In truth, the May 12, 1780 surrender of the vital southern port was a staggering blow to the Patriot war effort. Clinton enthusiastically claimed to have captured about 6,600 men, and without question, the Continentals of America’s Southern Army had been captured nearly en masse.[1] Additionally, the British were left in possession of a ponderous amount of rebel ordnance, ammunition, and supplies. But in the wake of the overwhelming victory, such a vast haul of rebel materiel would ironically lead to one of the worst disasters of the war.

On May 14, Maj. Peter Traille, Clinton’s chief of artillery, conducted an initial inventory of the captured stores. In addition to over three hundred pieces of artillery, the British were in possession of at least 5,416 muskets and well over thirty thousand rounds of fixed small arms ammunition. In the immediate aftermath of the capitulation, however, a thorough listing of captured arms was impossible. “Large Quantities of Musket Cartridges, Arms, and other small Articles” were not included in the return, reported Traille. “The scattered Condition of the different Stores not admitting of collecting them in so short a Time, a more exact Account will be given as soon as possible.”[2]

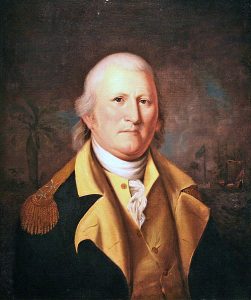

The following morning, British artillery officers, who were tasked with securing American munitions, were overwhelmed with even more captured rebel arms. The American militia, many of whom sat out the official surrender on May 12, were ordered to parade and give up their arms. American Maj. Gen. William Moultrie was somewhat amused that a fear of British retribution swelled the ranks of the militia to “three times the number of men we ever had on duty.” The citizen soldiers surrendered a motley assortment of weapons, which were loaded onto wagons and taken into the center of Charleston. However, there seems to have been a woeful disregard for basic safety protocols. American officers claimed to have warned the British that some of the muskets were loaded, however at least one weapon reportedly discharged from rough handling.[3]

In Charleston, the weapons were delivered to a storehouse which the Americans had used as an improvised arsenal. As a means of implementing Britain’s “southern strategy”, such a disparate collection of militia arms was earmarked for the eventual use of Carolina Loyalists.[4] The building held, in addition to arms, an American stockpile of roughly 4,000 lbs of fixed ammunition. Heading up the British work party at the arsenal was Capt. Robert Collins of the Royal Artillery; by most accounts, he was a competent professional and regarded as “a valuable officer.”[5]

Despite the intended use of the captured arms, Capt. Johann Ewald, a company commander in the Hessian Jaeger Corps, entered town that afternoon in the hope of acquiring a few of the muskets; either by purchase, or, he hoped, gratis through “the good offices” of Captain Collins. Accompanied by one of his lieutenants, Johann Wintzingerode, Ewald headed for the magazine where the arms were being secured. The pair was less than a hundred yards from the building when Ewald bumped into a servant who informed him that an old friend, Capt. Georg Wilhelm Biesnrodt, was sick in a nearby home.[6]

“Since I did not know how long the siege corps would remain together,” Ewald explained, he immediately decided to visit Biesendrodt and return to the storehouse later that afternoon. While his lieutenant waited in a nearby coffeehouse, Ewald accompanied the servant to Biesenrodt’s quarters, which was in the neighborhood. Ewald had just stepped through the door of the house when the unexpected happened.[7]

“Such an extraordinary blast occurred,” wrote Ewald, “that the house shook.”[8] It was, in fact, a thunderous explosion that rocked the entire city. General Moultrie, who just then was near the corner of Broad and Meeting Streets in the city center, recalled that the “houses of the town received a great shock, and the window sashes rattled as if they would tumble out of the frames.”[9] The shock waves terrified city residents, and Ewald recalled that “dreadful cries arose from all sides” of the town. When he ran into the street, the Hessian captain was dumbfounded. The storehouse which he had nearly entered not ten minutes earlier had clearly experienced a catastrophic accident; the sky above the building was filled with “a thick cloud of vapor.”[10]

The structure itself had been demolished by the explosion, which filled the sky with a deadly form of shrapnel.[11] “The muskets flew up into the air,” wrote Jaeger Capt. Johann Hinrichs, and “ramrods and bayonets were blown onto the roofs of houses.”[12] Immediately rushing to the building, Ewald was witness to deep horrors that he would never forget. The streets were littered with about sixty people “burnt beyond recognition, half dead and writhing like worms, lying scattered around the holocaust.” Amid the confusion, he lamented, “no one could help them.” The American militia, who were still milling about after surrendering their weapons, raced to the scene of the disaster and, joined by British troops and local slaves, frantically set to work fighting fires which had spread through the neighborhood. Ewald, generally an accurate and impartial witness, recorded that the danger was not quite passed. “Many of those who hurried to the scene,” he claimed, “were killed or wounded by the gunshots which came from the loaded muskets in the cellars.”[13] There was, however, little time to waste. The fires spread rapidly and eventually engulfed structures near the city’s primary powder magazine.[14] “At last,” reported Moultrie, “some timid person called out, that ‘the magazine was on fire.”[15]

Pandemonium ensued. Under the deluded fear that the main magazine was about to explode, workers fled in a contagious panic. Both British and Americans raced pell-mell through the streets in a virtual stampede. Were it not for the horrific nature of the disaster, the chaotic scene presented a comic spectacle. “I have heard some of them say,” remembered Moultrie, “that although they were so confoundedly frightened at the time, they could not help from laughing, to see the confusion and tumbling over each other.”[16]

When particulars of the disaster reached Moultrie near St. Michael’s Church, the general concluded that it was no laughing matter. Familiarized with the disposition of American arms and munitions, Moultrie immediately advised bystanders to get as far away from the city’s magazine as possible. The building was filled with a reported 10,000 pounds of powder and if ignited, he feared, “many of the houses in town would be thrown down.” Heading for safety at the shoreline of Charleston’s South Bay, Moultrie met with a British officer who was clearly agitated. When informed that the magazine contained such a ponderous amount of powder, the redcoat blanched and blurted out “Sir, if it takes fire, it will blow your town to hell!” Moultrie agreed; “it would give a hell of a blast,” he responded.[17]

In the wake of the disaster, Crown troops were understandably suspicious that the defeated Americans were guilty of sabotage. Nearing the relative safety of the shoreline, Moultrie was accosted by a furious Hessian officer. “You, General Moultrie,” shouted the German, “you rebels have done this on purpose, as they did at New York.” Taken into custody, Moultrie was confined in a nearby home with a number of other Americans, but succeeded in slipping out a note of protest to British Maj. Gen. Alexander Leslie. Leslie immediately dispatched a staff officer, who ordered off the Hessian guards and then offered Moultrie an apology for the incident.[18] Nevertheless, recorded an anonymous American subaltern, the British remained considerably alarmed. “Patrols in the streets till the fire was extinguished,” he wrote, “Their whole garrison under arms.”[19]

When work finally proceeded on fighting the blaze, a good bit of the neighborhood had been destroyed. Capt. John Peebles of the 42nd Foot recorded that “a Barrack, the gaol, & house of Correction, in which were a good many people,” was burnt, but by evening the flames were put out by the efforts of townspeople, militia, and slaves.[20] The smoldering ashes revealed a grisly sight. The tremendous power of the blast had left unspeakable devastation. Moultrie later claimed that the body of one unfortunate victim had struck the steeple of Charleston’s Independent Church, where marks of the incident were visible for days.[21] “We saw a number of mutilated bodies hanging on the farthest houses and lying in the streets,” wrote Johann Ewald, who witnessed charred arms and legs scattered in every direction. “Never in my life, as long as I have been a soldier,” concluded Ewald, “have I witnessed a more deplorable sight.” For a hardened veteran who had seen extensive action since the New York campaign, it was no mean observation.[22]

Precise figures for the number of victims to the disaster would remain elusive. Among the dead were Captain Collins, artillery Lieut. John Gordon, a lieutenant of the 42nd, 17 English and two Hessian artillerymen, and a Hessian grenadier. Perhaps the most unfortunate victims were the hapless civilians who lived near the scene of the explosion, not to mention “the lunatics and negroes,” wrote the unidentified subaltern, “that were chained in gaol for trifling misdemeanors.” Rumors abounded in the aftermath of the incident, and estimates of those killed by the blast ranged upwards of 300.[23] Perhaps the most reasonable estimate was that of Maj. William Croghan of the 1st Virginia, who informed a friend that “near a hundred lives” had been lost.[24]

Regardless of the exact figures, the incident was a tragic, and likely needless, loss of life. The precise cause of the disaster, however, will never be known for certain; everyone in a position to know exactly what occurred was killed by the explosion. The anonymous American subaltern who recorded the event in his journal wrote that although some of the British persisted in suspecting rebel duplicity in the catastrophe, “the more sensible” were certain that the explosion was occasioned by the rough handling of loaded muskets.[25] Such a conclusion came to be the general consensus. Johann Ewald, a fairly dispassionate observer, likewise thought that “as one might assume”, a musket discharged accidentally while being stored in the arsenal, igniting a powder keg. “The entire disaster had occurred,” he thought, “through carelessness.”[26] To Captain Peebles, who lost a fellow officer from the 42nd Foot, the entire affair was “a melancholy accident”, as well as a pointless disaster. “Very Strange Management,” he observed, “to Store up loaded Arms in a Magazine, of Powder.”[27]

For his part, Ewald viewed his narrow escape from the catastrophe with the grim resignation of a professional soldier. “From this incident,” he wrote, “I realized once more that if one still lives, it is destined that he shall live. One should do as much good as possible, trust firmly in the Hand of God, and go his way untroubled.”[28]

[1] Sylvanus Urban, ed., The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle, volume 50 (London: J. Nichols, 1780), 339. Letter, Sir Henry Clinton to Lord George Germain, June, 4, 1780. Clinton reported that he had taken 5,617 troops, plus an estimated 1,000 sailors. For a closer examination of the numbers, see Edward McCrady, The History of South Carolina in the Revolution, 1775-1780 (New York: MacMillan Company, 1901), 507-510.

[2] Franklin B. Hough, The Siege of Charleston, by the British Fleet and Army Under the Command of Admiral Arbuthnot and Sir Henry Clinton (Albany, New York: J. Munsell, 1867), 117-118. Major Peter Traille, Return of Ordnance and Ammunition in Charleston, May 14, 1780.

[3] William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, so far as it Related to the States of North and South-Carolina, and Georgia (New York: David Longworth, 1802), vol. 2, 108-109. See also William Gilmore Simms, South Carolina in the Revolutionary War (Charleston: Walker and James, 1853), 155. Both Moultrie and an unidentified American subaltern reported accidental discharges prior to the explosion.

[4] Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America (London: T. Cadell, 1787), 24. Tarleton indicated that the arms were “for the use of the friends to the British government in the province of South Carolina.”

[5] Roger Lamb, An Original and Authentic Journal of Occurrences During the Late American War, From its Commencement to the Year 1783 (Dublin: Wilkinson & Courtney, 1809), 296.

[6] Johann Ewald, Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal, trans. and ed. Joseph P. Tustin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 239.

[7] Ewald, Diary of the American War, 239.

[8] Ewald, Diary of the American War, 239.

[9] Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, 109-110.

[10] Ewald, Diary of the American War, 239.

[11] The exact location of the explosion is uncertain. Edward McCrady, History of South Carolina in the Revolution, 1775-1780 (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1901) places the explosion on Magazine Street between Archdale and Mazyck (now Logan) Streets, page 505. Moultrie, in Memoirs, wrote that one of the bodies struck the steeple of “the New Independent Church” which stood “a great distance from the explosion,” page 109. The present day Unitarian Church, 4 Archdale Street, is now on that site which is at the eastern end of Magazine Street.

[12] Bernhard A. Uhlendorf, ed., The Siege of Charleston, with an Account of the Province of South Carolina: Diaries and Letters of Hessian Officers from the Von Jungkenn Papers in the William L. Clements Library (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1938), 197-199.

[13] Ewald, Diary of the American War, 239.

[14] The Powder Magazine, which dates from about 1713, survived the threat of fire and is currently preserved as a museum. See www.powdermag.org. Located at 79 Cumberland Street.

[15] Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, 110.

[16] Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, 110.

[17] Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, 110-111.

[18] Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, 111.

[19] Simms, South Carolina in the Revolutionary War, 156.

[20] John Peebles, John Peebles’ American War: The Diary of a Scottish Grenadier, 1776-1782. Edited by Ira D. Gruber. (Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton, 1997), 374.

[21] Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, 109.

[22] Ewald, Diary of the American War, 239.

[23] Peebles, John Peebles’ American War, 374. Simms, South Carolina in the Revolutionary War, 155. Ewald, Diary of the American War, 239.

[24] Robert W. Gibbes, ed., Documentary History of the American Revolution: Consisting of Letters and Papers Relating to the Contest for Liberty, Chiefly in South Carolina…1776-1782 (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1857), vol. 2, 133. Letter, Major William Croghan to Michael Gratz, May 18, 1780.

[25] Simms, South Carolina in the Revolutionary War, 155.

[26] Ewald, Diary of the American War, 239.

[27] Peebles, John Peebles’ American War, 374.

[28] Ewald, Diary of the American War, 240.

2 Comments

I’ve been aching for someone to write about this incident: bravo. (Ok now I’ll read it.)

Had Ewald not been distracted, we may have lost of the finest diarists of the war! One must wonder, like New York in September 1776, was it indeed sabotage or the complacency of a victorious army after its victory? Traille must be the same gentleman who briefly commanded at Stony Point the previous year as a senior Captain of the 3rd RA. Very interesting article!