The phrase “fourteenth colony” describes a province in British North America that did not revolt alongside the original thirteen colonies. Such a province usually had one or more connections to the American Revolution. The phrase is misleading and has been thrown around freely in literature on the Revolutionary era. There have been at least eight provinces in British America labeled the fourteenth colony. They cannot all claim the same title.

The term typically describes an imagined or recognized territory/jurisdiction that, while it was not part of the original thirteen colonies, still engaged in and/or was affected by the American Revolution. The term points to a noteworthy revelation. Upon the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, the American colonies were no longer colonies at all; they became states. Going forward, this article will refer to each of the states as states only when appropriate. After all, some of the provinces listed in this article remained in British hands and were, in fact, still colonies by the end of the war.

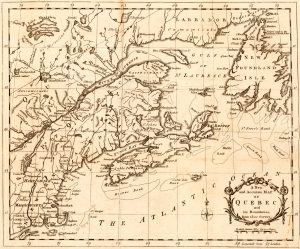

Nova Scotia

By 1776, New England emigrants made up a significant part of Nova Scotia’s population. Most Nova Scotians were sympathetic to the American rebels during the Imperial Crisis. By the early 1770s, Committees of Correspondence and Safety appeared around Nova Scotia. Insurrection rocked the province when insurgents burned hay that was intended for the British army in Boston. In 1775, George Washington sent two spies to determine whether or not Nova Scotia was ready for rebellion. In March 1776, a Nova Scotian delegation met with Washington to discuss fomenting a rebellion in their province. Washington declined to aid the delegates and refused to invade Nova Scotia. During the first few years of the Revolutionary War, American privateers raided Nova Scotia’s coast. On such forays, they destroyed several trading and fishing vessels. Not surprisingly, those acts alienated many Nova Scotian residents against the cause. In the end, four main reasons point to why Nova Scotia never joined the rebellion. Influential clergymen kept dissenters in check; the long distances between Nova Scotia’s settlements hurt the rebel’s chances of organizing an effective resistance base; a large British military outpost at Halifax intimidated troublemakers; and rebel raids alienated otherwise sympathetic Nova Scotians. After the war, roughly 20,000 to 30,000 loyalist refugees resettled in Nova Scotia.[1]

Quebec

In September 1775, Washington authorized a two-pronged invasion of Canada. He was actually referring to the province of Quebec. French-Canadian citizens in Quebec were invited to join the rebellion in 1774 and again in 1775.[2] The Canadians never responded to either of Congress’s invitations. Operating under the belief that Quebec was poorly defended, Congress resolved to launch an invasion against that colony. The invasion force was separated into two expeditions. Gen. Philip Schuyler commanded the first, consisting of over 1,700 men who set out from New York and travelled down Lake Champlain into Canada. Schuyler planned on taking Montreal before he would meet up with the second expeditionary force at Quebec. Benedict Arnold commanded the second expedition, an 1,100-man force that set out from Massachusetts, landed at the mouth of the Kennebec River in Maine on September 19, 1775, and trekked through the wilderness to Quebec. Arnold’s force endured the bitter winter in the wilderness. After suffering hunger, fatigue, and the cold, they reached Quebec in early November. Meanwhile, Schuyler fell ill, and command of his expedition fell to Gen. Richard Montgomery. Montgomery went on to take Montreal before he finally reached Quebec in December. Together, both forces laid siege to Quebec until May 1776. Faced with the looming prospect of British reinforcements, the tired American army withdrew. Throughout the war, Congress considered retaking Quebec, but Washington was against it. He considered Quebec a low priority. Instead, he preferred to divert desperately-needed resources to the main war effort. Consequently, no more serious attempts at taking Quebec were ever made and the province remained in British hands for the remainder of the war. Several former British and French Canadians fled Quebec with the Americans. They went on to fight in many engagements and were even present at Yorktown, Virginia. New York land was doled out to them after the war. During the Paris peace talks, the Americans unsuccessfully tried to gain Quebec.[3]

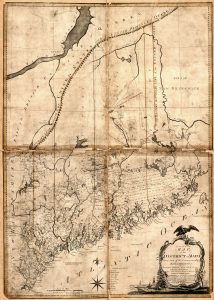

Maine/New Ireland

In the early stages of the American Revolution, Maine served as a buffer zone between loyal Nova Scotia and the rebellious Massachusetts. Much of eastern Maine was occupied by the British throughout the war. Machias, a small town in eastern Maine, however, was a bastion of rebel sympathizers. In 1775, the first naval battle of the American Revolution took place here. It was called the Battle of Machias. The battle was an American victory and resulted in the British warship Margaretta’s capture. In retaliation, British Admiral Samuel Graves, then in Boston, ordered Capt. Henry Mowat to burn Falmouth (present-day Portland). Mowat gave the Portlandians one night to vacate the town. In response, some fired at him. He returned the favor. The next day, Portland burned. In total, 400 buildings were destroyed, two American ships captured, and eleven more sunk. Machias was a battle site again in 1777 when British forces under the command of Sir George Collier attempted to raid the town. With the aid of their Native American allies, American forces successfully repelled the attack. In 1779 British leadership captured some territory in Maine, largely around Penobscot Bay. They wanted to create a new Crown colony there called “New Ireland.” New Ireland became a loyalist haven and military base during the war. In response to British interests in the region, the Massachusetts Commonwealth dispatched the Penobscot Expedition in an attempt to dislodge the northern British presence. The Penobscot Expedition was a resounding American defeat. British reinforcements routed the rebels after an unsuccessful twenty-one-day siege of the British-held Fort George. The expedition cost eight million dollars and forty-three lost ships. After the war, Maine was turned over to the Americans during the Paris peace settlement. Many Maine loyalists relocated in Canada.[4]

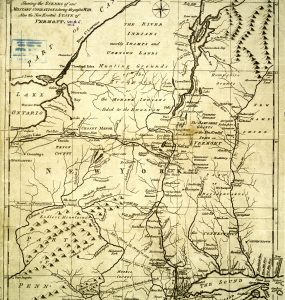

The Republic of Vermont

Pre-Revolutionary Vermont never really got along with its neighbors. Border disputes with New York and New Hampshire caused many Americans to view Vermonters as a group of troublemakers. Despite these early tensions, Vermont nevertheless aided the revolutionary cause. In 1775, Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain Boys, a force of Vermont militia, seized British-held Fort Ticonderoga. In spite of their help, the Continental Congress refused to recognize Vermont’s legitimacy. So, in January 1777, Vermont declared itself a sovereign nation, the Republic of Vermont. Vermont’s nationhood came complete with its own currency, president, and constitution. In 1780, Ethan Allen and a few others engaged in secret negotiations with the British in Quebec. Purportedly, they claimed the talks were about securing the release of some of their captured militiamen. In actuality, they sought to hammer out a separate deal with the British just in case the Americans lost the war. They even entertained thoughts of returning to the empire’s fold. When word reached the Vermont Assembly about these negotiations, a scandal of epic proportions broke out. This event is called the Haldimand Affair, named after Frederick Haldimand, Quebec’s governor. The Haldimand Affair was so damaging to Vermont’s reputation, the Continental Congress considered invading the republic to gain a more secure control over the region. Fortunately for the Americans, the negotiations went nowhere. By 1791, Vermont joined the United States.[5]

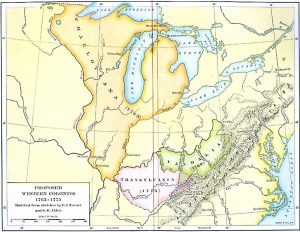

Vandalia/Westsylvania

In the 1770s, American land speculators carved out the boundaries of a colony in modern-day West Virginia. It was called Vandalia. In 1772, the Privy Council approved the petition for this colony’s formation. Vandalia was named after British Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, in honor of her Vandal ancestry. The colony’s boundaries were defined in May 1773. They followed the Kentucky River from its mouth to its source; from there it ran to the intersection of the Holston River and the Virginia/North Carolina border; from that border it moved east to New River. A line ran along New River to the mouth of the Greenbrier, which it followed along its northeast branch, across the Alleghenies, until it met Lord Fairfax’s line. It ran along the Fairfax line to the headsprings of the north branch of the Potomac River where it intersected the Maryland boundary. The line then followed the Maryland boundary northward to the southern boundary of Pennsylvania before it moved along the Monongahela and Ohio back to the mouth of the Kentucky. According to historian Otis K. Rice, “all of West Virginia west of the crests of the Alleghenies was included within the boundaries of the proposed colony.” By 1776, Virginia’s interests in western land and the exploding tensions between Britain and the American colonies hindered Vandalia’s development. During the Revolutionary War, settlers living within the region of Vandalia’s proposed boundaries petitioned the Continental Congress to recognize the area as the fourteenth state. They called it Westsylvania. Virginia and Pennsylvania put forth efforts to bar Westsylvania’s entry into the Union largely because they each claimed land in the region that they believed was rightfully theirs. In the end, Congress refused to recognize Westsylvania as an independent state.[6]

Kentucky/Transylvania

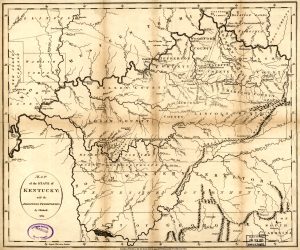

In 1774, North Carolinian judge and land speculator Richard Henderson formed a land speculation company; he and his investors dubbed it the Transylvania Company in January 1775. In March 1775, the Transylvania Company purchased twenty million Kentucky acres from the Cherokees under the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals. The land transfer made up what is now the central and eastern parts of Kentucky. This deal is sometimes referred to as the Transylvania Purchase. It occurred at an inopportune time. The Proclamation of 1763 barred the creation, development, and settlement of any non-Crown-sanctioned colony. Further complicating matters, Virginia and North Carolina both claimed the lands that were allegedly illegally transferred over to the Transylvania Company under the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals. Later on, this last point would prove problematic for the Transylvania Company. Regardless of the opposition against its creation and development, Transylvania’s settlement proceeded at a quick pace.

Daniel Boone and his famed Wilderness Road opened Kentucky to settlement. Boonesborough, the intended capital of Transylvania, was established in 1775. Several other settlements, like Harrodsburg, sprang up around the same time which helped populate the frontier region. A problem emerged. Many people arrived independently and without any connection to the Transylvania Company. Consequently, numerous settlers did not respect or recognize Transylvania’s authority. In any case, a few of the more consequential settlements that together formed the smattering of whatever population existed in the Kentucky wilderness, got together in May 1775 and organized a frame of government known as the Transylvania Compact. After the compact’s business was resolved, Henderson petitioned the Continental Congress to recognize Transylvania as a legal state. Congress could not reach a decision without Virginia or North Carolina’s consent, and both claimed jurisdiction to lands directly situated within Transylvania’s borders. In June 1776, Virginia barred the Transylvania Company from exercising authority over settlers who Virginia believed fell under their jurisdiction.

While Transylvania’s existence waned in political and legal arenas, militia units were organized to repel Indian attacks. During the Revolutionary War, Native Americans raided Kentucky settlements in search of scalps— scalps the British paid well for. In December 1776, Virginia formed Kentucky County which comprised much of Transylvania. The Virginia Assembly provided the Kentucky County militia with 500 pounds of gunpowder to aid their defense against Indian incursions. When George Rogers Clark raided Kaskaskia and Vincennes in the Illinois Country, Kentucky militia went with him. In September 1778, Boonesborough was besieged by a large force of British-supplied Native Americans. By December 1778, Virginia declared Transylvania’s claim to Kentucky land null and void. In 1780, Kentucky County was divided into Fayette, Lincoln, and Jefferson counties. In 1782 the Battle of Blue Licks, Kentucky, was one of the last battles of the American Revolution. In the end, Transylvania never became anything more than an idea. Had Transylvania been recognized by the Continental Congress, it would be remembered today as the proverbial fourteenth colony.[7]

East Florida

East Florida was organized in 1763 after the Seven Years’ War. East Florida’s boundaries encompassed the entire Florida peninsula proper. The Gulf of Mexico and the Apalachicola River formed its western boundary; a line from the Apalachicola to the point where the Chattahoochee and Flint Rivers meet the source of the St. Mary’s River and from that point to the Atlantic Ocean made up the northern boundary; and the Atlantic Ocean formed the eastern and southern boundaries. East Florida’s settlement was concentrated in the northeast corner of the province. After news of the Declaration of Independence reached St. Augustine, the province’s capital, effigies of John Hancock and Samuel Adams were burned in the streets. During the Revolutionary War, East Florida served as a haven for loyalists escaping persecution and violence. By 1775, Congress placed an embargo on East Florida. From 1776 onwards, thousands of loyalists relocated to St. Augustine. Three American invasions attempted to conquer East Florida in 1776, 1777, and 1778. Two large-scale Revolutionary War battles were fought on East Florida’s soil, the Battle of Thomas Creek, 1777 and the Battle of Alligator Creek Bridge, 1778.

On multiple occasions, East Florida threatened to invade Georgia during the early years of the war. As such, Georgia was forced to divert resources to the protection of its southern borders or else risk raids and regional instability— something the state largely failed to stop. In addition to threatening the rebels in the south, East Florida supplied raw materials to sugar plantations in the British West Indies— an important contribution after 1775 when the rebellion upset prior trade arrangements between Britain’s Atlantic seaboard colonies and the West Indies. During the war, three South Carolinian signers of the Declaration of Independence were imprisoned in St. Augustine’s Castillo de San Marcos: Thomas Heyward, Jr., Arthur Middleton, and Edward Rutledge. After the war, Spain reacquired East Florida in 1783. From 1783 to 1785, East Florida absorbed the last loyalist refugees from the southern colonies who sought to relocate to other parts of the British Empire. While Savannah and Charleston were both evacuated in 1782, St. Augustine was still evacuating in 1785.[8]

West Florida

West Florida was organized in 1763 after the Seven Years’ War. The Apalachicola and Chattahoochee Rivers made up West Florida’s eastern boundary; the Gulf of Mexico its southern boundary; the Mississippi River its western boundary; and a line drawn east from the confluence of the Yazoo and Mississippi Rivers the northern boundary. Such an expanse of territory encompassed the present-day states of Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Pensacola became the colony’s designated capital. During the Imperial Crisis the anti-British movement had little effect on West Florida, largely because the province was so far removed from the rebellion. The Stamp Act was the only British tax that sparked any uproar in the colony and dissent there was nothing rebellious in nature. In 1774, the First Continental Congress resolved to send a letter to West Florida inviting them to join the rebellion. West Florida did not respond. By 1775, Congress banned trade with West Florida. During the Revolutionary War, West Florida served as a haven for loyalists escaping persecution. In 1778, Capt. James Willing sailed down the Mississippi River and raided West Florida settlements. Contrary to the expedition’s aims, Willing’s raids further entrenched West Floridians’ attachment to the Crown. When Spain entered the war in 1779, Louisiana Governor Bernardo de Galvez sought West Florida’s conquest. From 1779 to 1781, Galvez amassed an army and invaded West Florida. This Gulf Coast campaign ended in 1781 after the Siege of Pensacola. Thereafter, West Florida became a Spanish colony once more. The province would never fall under British jurisdiction again.[9]

[1]For more on Nova Scotia see Emily P. Weaver, “Nova Scotia and New England During the Revolution,” The American Historical Review10, no. 1 (Oct. 1904): 52-71; John Hanc, “When Nova Scotia Almost Joined the American Revolution,” Smithsonianmag, June 5, 2017, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/when-nova-scotia-almost-joined-american-revolution-180963564/; Dana Benner, “The Fight for the ‘14th Colony,’ Nova Scotia,” HistoryNet, January 2020, www.historynet.com/the-fight-for-the-14th-colony-nova-scotia.htm.

[2]“Letter from Congress to the “Oppressed Inhabitants of Canada,” 29 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jay/01-01-02-0078; original source: The Selected Papers of John Jay, vol. 1, 1760–1779, ed. Elizabeth M. Nuxoll (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010), 116–118.

[3]For more on Quebec see Mark R. Anderson, The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony: America’s War of Liberation in Canada, 1774-1776 (Lebanon: University Press of New England, 2013); Harrison Bird, Attack on Quebec: The American Invasion of Canada, 1775 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968); Thomas A. Desjardin, Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold’s March to Quebec, 1775 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2006); Robert McConnell Hatch, Thrust for Canada: The American Attempt on Quebec in 1775-1776 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1979).

[4]For more on Maine/New Ireland see James S. Leamon, Revolution Downeast: The War for American Independence in Maine (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1993); George E. Buker, The Penobscot Expedition: Commodore Saltonstall and the Massachusetts Conspiracy of 1779 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2002).

[5]For more on The Republic of Vermont see David Bennett, A Few Lawless Vagabonds: Ethan Allen, the Republic of Vermont, and the American Revolution (Philadelphia: Casemate Publishers, 2014); Christopher S. Wren, Those Turbulent Sons of Freedom: Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain Boys and the American Revolution (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018).

[6]For more on Vandalia/Westsylvania see Neal O’ Hammon, Virginia’s Western War: 1775-1786 (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002); Otis K. Rice, The Allegheny Frontier: West Virginia Beginnings, 1730-1830 (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1970); James Donald Anderson, “Vandalia: The First West Virginia?” West Virginia History40, no. 4 (Summer 1979): 375-392; Harold Frederic and William C. Frederick, III, The Westsylvania Pioneers, 1774–1776 (Butler, PA: Mechling Bookbindery, 1991).

[7]For more on Kentucky/Transylvania see Thomas Perkins Abernethy, Western Lands and the American Revolution (New York: Russell & Russell, 1959); William R. Nester, The Frontier War for American Independence (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2004).

[8]For more on East Florida see Charles Loch Mowat, East Florida as a British Province, 1763-1784 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1943); Dr. Roger Smith,The 14th Colony: The American Revolution’s Best Kept Secret (St. Augustine: Colonial Research Associates, 2011); J. Leitch Wright Jr., Florida in the American Revolution (Gainesville: The University Presses of Florida, 1975).

[9]For more on West Florida see J. Barton Starr, Tories, Dons, and Rebels: The American Revolution in British West Florida (Gainesville: The University Presses of Florida, 1976); Cecil Johnson, British West Florida, 1763-1783 (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1971); John Appleyard Agency, The 14th Colony: British West Florida, 1763-1781 (Pensacola, FL: Pensacola Home & Savings Association, 1978); Mike Bunn, Fourteenth Colony: The Forgotten Story of the Gulf South During America’s Revolutionary Era (Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020).

5 Comments

Interesting article. While I knew at least a bit about each of the regions discussed, I had never put them all together under a fourteenth-colony heading. And, thanks for the additional-reading notes–I’ll be taking advantage of many of those sources.

A couple points about Vermont. Refering to it as a “republic” is a nineteenth-century creation. In the eighteenth century, nobody called it a republic. Vermonters consistently refered to themselves as a “state.” And, if you happen to believe in the saying, “follow the money,” ponder this–those involved in the Haldimand negotiations just happened to control thousands of acres and a trading base in the area around modern Burlington. It might well be they thought to protect their interests by forestalling British and Indian raids out of Canada.

Hello Mike,

I intended this article serve as a reference, starting, or jumping-off point for anyone looking into one or many of the various fourteenth colonies. Your utilization of my additional reading notes means my article is serving its purpose. That makes me happy.

This was an interesting take on happenings during the Revolution. Being from Indiana, it would be of interest to expound on just how much the French loaned to the U.S. with Lafayette here to offer physical assistance as well as monies. I truly believe without France we would still be New England.

I was disappointed with the article’s coverage of the revolution in Nova Scotia. The fact that Western Nova Scotia (Sunbury County) spontaneously revolted was overlooked, as were the two invasions by Eddy and Allen. This was also the only area that I am aware of where a spontaneous rebellion was successfully suppressed by the British. Otherwise, an interesting article.

As a resident of Pensacola, I was thrilled to read Mike Bunn’s recent book about West Florida earlier this year. Scholarship on such a specific, short-lived British colony is sparse, so I was very happy to see your references to a few other books covering this area during the Revolutionary War as well. Will definitely check them out!