The vast eastern province of Massachusetts, now the state of Maine, was the site of some important military events during the Revolutionary War. Several involved British naval lieutenant Henry Mowat, who would be called the “Villain of Falmouth,” “Mad Henry,” “The Execrable Monster” and the “Miscreant of the Revolutionary War.”

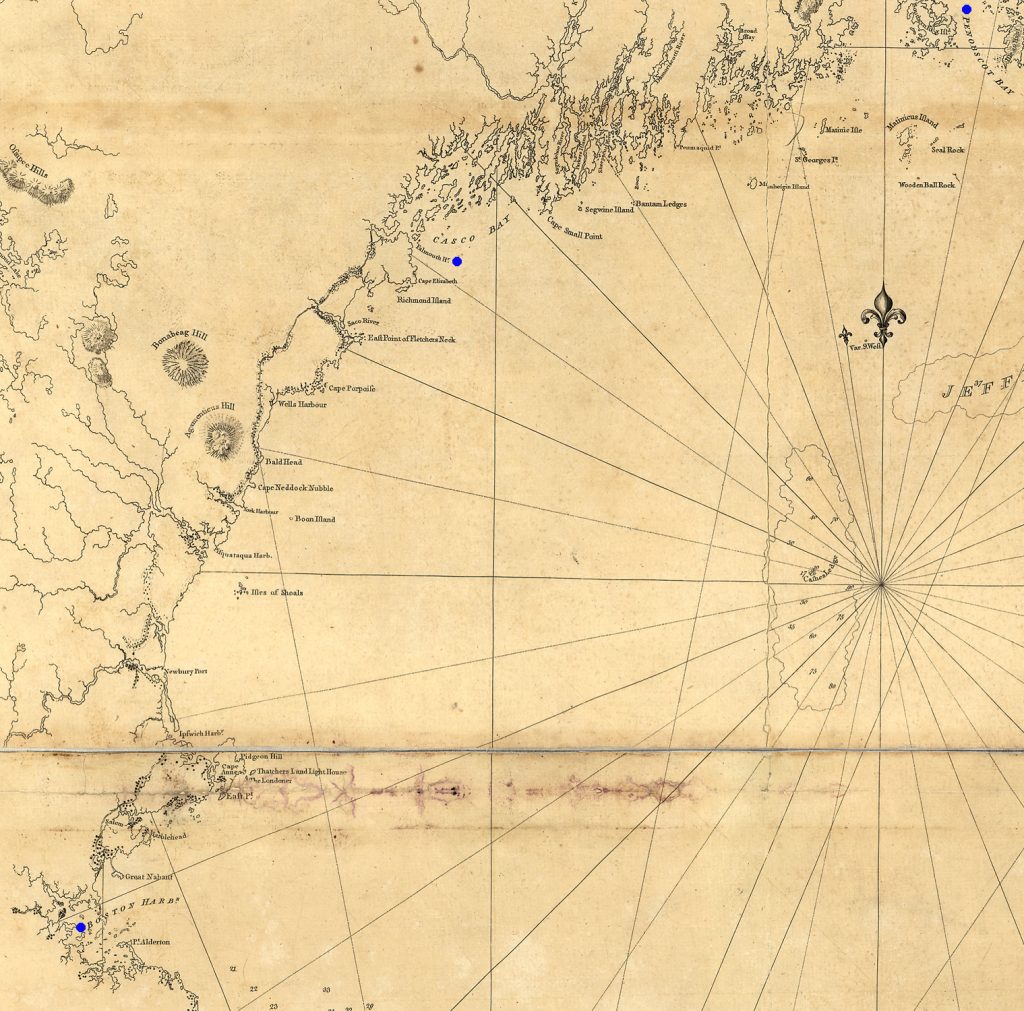

Mowat spent most of his professional naval career on duty in the Gulf of Maine. Born in Scotland in 1734 into a well-respected naval family, he received his lieutenant’s commission on January 22, 1758. Taller than most of men of the time, Mowat had an athletic build, a fair complexion, a square jaw, aquiline nose, and imposing military presence. His first command, in 1764, was the eight-gun Canceaux upon which he served for twelve years. The Canceaux, a converted merchant ship, was assigned to perform survey work along the northeastern coast based at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, at the mouth of the Piscataqua River.[1]

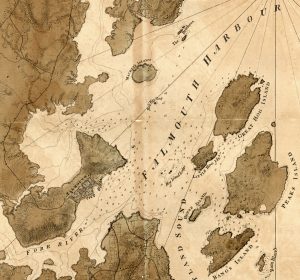

In April 1775 royal authority in Boston sent a naval ship to break an embargo perpetrated by troublemakers against His Majesty’s loyal subjects living in several communities on Massachusetts’s north shore and farther east along the Gulf of Maine. Mowat, en route to Halifax, was diverted to Falmouth (Portland) to maintain civil order. The appearance of an armed warshipin Falmouth harbor created tensions as news of the battles of Lexington and Concord had reached the Province of Maine. Upon learning of the warship’s arrival, elected militia leader Col. William Thompson from nearby Brunswick arrived at the town with about fifty men, “each with a bough of Spruce in his hat, and having a spruce pole with a green top on its standard.”[2] While Mowat and his landing party, the ship’s surgeon and Rev. John Wiswall, were negotiating with local Falmouth officials, Thompson’s band took them captive creating apprehension on both sides. The militia colonel was reluctant to give up his captives, but when the Canceaux’s second in command learned about the events on shore, he ordered two rounds fired harmlessly in the direction of the town as a warning to release Mowat and his contingent.[3]

The town’s authorities implored Thompson and his men to free Mowat. Complicating the deliberations, approximately six hundred armed and unruly militiamen from the nearby towns of Gorham, Cape Elizabeth, Scarborough, and Wyndham had swarmed into Falmouth to harass local Tories. The community’s own militia was unable to defend the town, because many members had already left to join the Continental Army and the remainder were preoccupied with the preservation of their own persons and property. The port of Falmouth was under an ominous British naval threat, overrun by a ragtag militia of neighboring fellow citizens, and essentially held captive by Thompson’s inopportune hostage taking. The militia leader, not thinking his plan through, was not sure what to do with a British captain.

In an act of good judgment, Thompson released Mowat on parole.[4] The ship captain agreed to the terms of his parole and was honor-bound to keep them. He was released to return to his ship, but was told to return ashore in the morning to complete the negotiations. Local moderate Whigs Enoch Freeman and Jedediah Preble were held as a guarantee of Mowat’s return.[5] Around the time the parole was being negotiated, the British sailors who had taken Mowat’s party ashore overheard some citizens discussing plans to kill the captain when he returned the next day.[6] The seamen reported the conversation to Mowat who decided that since the people of Falmouth were not living up to their agreement, it was obviously too dangerous to honor the conditions of the parole.

Local loyalists were quite worried when they learned why Mowat stayed onboard Canceaux. A group of them rowed out to the warship to express their concern that as British citizens they were entitled to the protection of the crown. They expressed it in the following statement: “[We appreciate] your courteous and kind behavior to all the Friends of Government [and] flatter ourselves with pleasing prospect of a Continuance of your Protection. [We regret that you are leaving us as] prey to the Sons of rapine and lawless Violence.”[7] The Americans also feared reprisal if other ships of the Royal Navy heard of the slight to one of their officers. The British lieutenant appeared to understand their concerns, and thus the citizens of Falmouth felt they had no reason to fear retribution. After several days the Canceaux sailed into Casco Bay along with a vessel carrying many Falmouth Tories to the temporary safety of Boston.

On June 26, 1775, the Journal of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress published an opinion that Colonel Thompson’s conduct was “friendly to his country and the cause of liberty.”[8] They perhaps failed to perceive that Thompson’s seizure of a royal naval officer prompted the British Boston-based command to consider a retaliatory move designed to intimidate a Maine coastal population of wavering loyalty and force them to submit to the authority of the king.

Captain Mowat, who had spent more than a decade surveying the New England coast, knew these waters and settlements better than most other North American naval commanders. On October 6 Vice Admiral Samuel Graves ordered Mowat “to Chastise” a number of coastal communities including Falmouth and Casco Bay: “you are to go to all the above Places as you can and make the most vigorous Efforts to burn the Towns and destroy the shipping in the Harbours.”[9]

Mowat obeyed his orders and first chose to attack Falmouth before the other towns included in his orders. Falmouth’s inhabitants had clustered close together for protection from hostile Indian incursions thus making the community an ideal target for a demoralizing bombardment. In addition, it was the place where he had been held captive a few months earlier, an insult to his position as a Royal Navy officer. On the other hand, now acquainted with the town’s leaders, he may have thought that he could convince the local citizens of Falmouth to pledge their loyalty to the crown, give up armed resistance, and save themselves from the admiral’s proclamation.

On October 16 a flotilla of four British warships sailed into Falmouth harbor. Most of the people of Falmouth regarded the squadron’s presence as unwelcome but not an unusual occurrence. British warships had frequently confiscated livestock from the nearby islands and commandeered local provisions to feed British troops in Boston. The next morning the squadron’s cannons were aimed menacingly at the most populated portion of the town. Anxiety decreased when it became known that Captain Mowat was in command of the vessels. Because Falmouth’s leaders had gained his release from Thompson and his rebels not long ago, they assumed that he could be reasoned with. Mowat anchored his vessels in a carefully preplanned formation and sent an officer ashore to read a dictum to the citizens of Falmouth. In this directive he said,

After repeated instances you have experienced in Britain’s long forbearance of the Rod of Correction; and the Merciful and Paternal extension of her Hands to embrace you, again and again have been regarded as vain and nugatory: And in place of a dutiful and grateful return to your King and Parent state, you have been guilty of the most unpardonable Rebellion, Supported by the Ambition of a set of designing men. . . [My orders are to] execute a just Punishment on the town of Falmouth. . . I shall give you the time of two hours, at the period of which a Red pennant will be hoisted at the Main top gallant Masthead with a gun but should your imprudence lead you to show the least resistance, you will in that case free me of that Humanity, so strongly pointed out in my orders as well as my own inclination. I also observed that all those who did upon a former occasion fly to the King’s ship under my Command for Protection, that the same door is now open and ready to receive them. The officer who will deliver this letter I expect to return unmolested.[10]

Upon receiving Mowat’s notice, a committee of local leaders rowed out to meet the lieutenant to inquire about possible options. Mowat’s orders did not authorize him to bargain with locals or even to warn them of an in eminent attack. In spite of this, perhaps in the tradition of chivalrous conduct, he decided to risk the vice admiral’s displeasure by attempting to find a way to avoid a bombardment. Mowat said that he would take it upon himself to deviate from his orders and allow the inhabitants of Falmouth to leave the settlement before opening fire. If the residents surrendered all of their arms by the following morning and swore allegiance to the King George III, the town could be spared.[11]

When the committee revealed the details of Mowat’s ultimatum, panic ensued in the town. Children and the elderly were evacuated and many personal valuable possessions were removed to the safety of the countryside. By daybreak with many people evacuating the town, what was left of the militia assembled a collection of arms for Mowat’s inspection. It became obvious that the best muskets and pistols had been hidden away for safekeeping, setting up the community for catastrophe.

The local committee attempted to stall the inevitable but were summarily escorted off the ship and taken ashore. At mid-morning Mowat had his vessels fire upon Falmouth’s largely-wooden buildings. The small armada bombarded the settlement throughout the morning. No lives were lost, but hundreds of buildings were razed and ruined. Two of the thirteen merchant ships that had been entrapped in the port were seized by Mowat and the rest destroyed.

Mowat’s bombardment was headline news in the American, British, and French press. British opinion was divided. John Adams, who occasionally visited Falmouth as a barrister, was deeply saddened by the events in Maine and had become convinced that secession was inevitable.[12] Samuel Adams, his provocateur cousin, became even more zealous in his quest for independence. The destruction seemed unjustified by the actions that preceded it. Some considered the assault an affront to the people of Falmouth who were, at the time, still British citizens possessing the rights of protection by the crown. The French thought this act a military and political blunder. Mowat’s actions certainly fulminated public opinion and contributed to the movement towards independence.

Lt. Henry Mowat had orchestrated both the destruction of Fort Pownal and the burning of Falmouth in 1775. In 1779, he commanded the British naval defense at Bagaduce (Castine) that led to the disastrous American Penobscot Expedition.[13] Apparently somewhat unappreciated, Mowat attained the rank of captain at the relatively advanced age of forty-eight. After about forty-five years of naval service, in 1798 the sixty-four-year-old Mowat died of an apparent stroke onboard his last command, HMS Assistance, off America’s coast.[14]

[1]A record of Mowat’s voyages on the Canceauxis found in Abridged Logs of the H.M. Armed Ship Canceaux, transcribed by Andrew L. Wahil (New York, NY: Heritage Books, 2003).

[2]William Bell Clark, ed. Naval Documents of the American Revolution, 1: 307.

[4]James S. Leamon, Revolution Downeast: The War of Independence in Maine (Amherst: MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1993), 66.

[6]Clark, Naval Documents of the American Revolution,1: 328.

[12]David G. McCullough, John Adams (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2001), 63, 71.

[13]Louis Arthur Norton, “The Penobscot Expedition: A Tale of Two Indicted Patriots,” The Northern Mariner vol. 16 no. 4 (October 2006), 1-28.

[14]Louis Arthur Norton, “Henry Mowat: Miscreant of the Maine Coast,” Maine History vol. 43 no.1 (2007), 18.

One thought on “The Marauder and Malefactor of Maine”

Wonderful article and thank you for educating me on the burning of Falmouth and introducing me to Henry Mowat!