On June 13, 1775, writing from Crown Point on Lake Champlain, Benedict Arnold reported to the Continental Congress that Britain had only 550 “effective men” guarding all of Canada. Further, according to his intelligence, “great numbers of the Canadians” were “determined to join us whenever we appear in the Country with any force to support them.” Why not take advantage of the situation, before Britain could send reinforcements? “If the honourable Congress should think proper to take possession of Montreal and Quebeck, I am positive two thousand men might very easily effect it …. I beg leave to add, that if no person appears who will undertake to carry the plan into execution, (if thought advisable,) I will undertake, and, with the smiles of Heaven, answer for the success of it, provided I am supplied with men, &c, to carry it into, execution without loss of time.”[1]

Congress liked the idea but chose Philip Schuyler, not Arnold, to lead the expedition. Arnold would not be left out, however. George Washington soon gave him command of a second invading force, “a Detachment of 1000 or 1200 Men” that would proceed through Maine, upstream along the Kennebec River until it reached the St. Lawrence watershed. This would “make a Diversion,” Washington explained to Schuyler, forcing the British Gen. Guy Carlton to “break up” his forces.[2]

Washington and Arnold had no difficulty finding volunteers for the Kennebec expedition. Yankees steeped in the Protestant faith jumped at the opportunity to invade the stronghold of Catholicism on their northern border. The Quebec Act had recently placed all lands west of the Appalachians off-limits for settlement and under Canadian control; it had also granted official recognition to the Catholic Church in Quebec. Invading Canada would strike a blow at two tyrants at once: the British monarch and the pope. One army chaplain spoke for many when he wrote in his diary: “Had pleasing views of the glorious day of universal peace and spread the gospel through this vast extended country, which has been for ages the dwelling of Satan, and reign of Antichrist.”[3] After attending divine service at the First Presbyterian Church in Newburyport, their point of departure, some of Arnold’s men convinced the sexton to open the tomb of George Whitefield, the famous revivalist of the Great Awakening, which lay within the church. Whitefield’s body had decomposed in the five years since his death, but some of his clothes remained intact. The men cut his collar and wristbands into small pieces, which they used as relics to ensure success in conquering a land peopled by heathens, Catholics, and their British rulers.[4]

Such zeal worried George Washington. Sensing that Arnold’s men (English speaking, white, and Protestant) did not respect the predominant culture and customs of Canada’s inhabitants (mostly French speaking, many with Indian blood, and Catholic), Washington instructed Arnold:

As the Contempt of the Religion of a Country by ridiculing any of its Ceremonies or affronting its Ministers or Votaries has ever been deeply resented, you are to be particularly careful to restrain every Officer and Soldier from such Imprudence and Folly and to punish every Instance of it … You must carefully inculcate upon the Officers and Soldiers under your Command that not only the Good of their Country and their Honour, but their Safety depends upon the Treatment of these People … If they [Canadians] are averse to it [the military expedition] and will not co-operate, or at least willingly acquiesce, it must fail of Success. In this Case you are by no Means to prosecute the Attempt; the Expence of the Expedition, and the Disappointment are not to be put in Competition with the dangerous Consequences which may ensue, from irritating them against us, and detaching them from that Neutrality which they have adopted.[5]

The march of Arnold and some 1,100 adventuresome men through Maine’s “direful howling wilderness” (as one man wrote in his journal) is well documented. In 1938 Kenneth Roberts published thirteen journals and Arnold’s letters in a book titled “March to Quebec,” an indispensable source.[6] Most of the journals Roberts included were written by officers; several were composed afterwards, some even copied from other journals. Here, I feature a lesser-known source, the diary of Jeremiah Greenman, a seventeen-year-old private from Rhode Island, and tell a lesser-known story, that of Maj. Timothy Bigelow, a blacksmith from Worcester who served as one of Arnold’s four field officers.

Greenman opened his diary with the departure from Newburyport on September 19: “Early this morn. waid anchor with the wind at: SE a gale our Colours fliing Drums a beating fifes a plaing the hils and warfs a Cover biding thair friends fair well.” In following weeks, the young private detailed the difficulties the adventurers encountered as they tried to navigate their flat-bottomed boats, called bateaux, up the Kennebec River to the Canadian border. They rowed, swam, and dragged their boats, alternately buried in “mud and mire” or fighting against a current that was “very swift indeed.” Sometimes they had to portage for miles. On October 7 Greenman reported: “this day left all Inhabitance & enter’d an uncultivated co [country] and a barran wilderness.” The next day “it began to wrain,” and five days after that “Sum small Spits of Snow” fell.[7]

That was only the beginning. The journey took longer than Arnold had envisioned, while food was consumed more quickly. On October 24 Greenman reported: “our provision growing scant sum of our men being sick held a Counsel agreed to send the Sick and wekly men back.” But more than the sick and weakly opted to return: “Colo Enoss with three Companys turn’d back and took with them large Stores of provision and ammunition which made us shorter than we was before.” (Upon his return to Massachusetts, Lt. Col. Roger Enos would be court martialed but acquitted for “quitting his commanding officer without leave.”)[8]

One week later, Greenman wrote:

T 31. Set out this morn very early left 5 sick men in the woods … to the mercy of wild beast … our provision being very Short hear we killed a dog I got a small peace of it and sum broth that is was boyled with a great de of trubel then, lay down our blancots and slep very harty for the times.

November 1775 by Shedore [Chaudiere River, which flows into the St. Lawrence]

W 1. … In a very misrabel Sittiuation nothing to eat but dogs hear we killed a nother and cooked I got Sum of that by good [luck] with the head of a Squirll with a parsol of Candill wicks boyled up to gether wich made very fine Supe without Salt hear on this we made a nobel feast without bread or Salt thinking it was the best that ever I eat & so went to Sleep contented…

T 2. this morn when we arose many of us so weak that we could hardly stand we stagerred about like drunken men.

Finally, on the afternoon of November 2, they emerged into settled territory and some cattle: “hear we killed a creatur and Sum of ye men so hungrey before this Creater was dressed thay had the Skin and all entrels guts and every thing that could be eat on ye fires a boyling.”

If Timothy Bigelow kept a diary of the march to Quebec it is not extant, but two of his letters survive, and he is mentioned in journals written by others and in official records. Bigelow, age thirty-six, had established impeccable credentials as a revolutionary. His blacksmith shop was a hub for Worcester’s radical activists who cast off British rule in the late summer of 1774. He was the town’s representative to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress when Worcester issued the first known call for a new and independent government in October 1774. At the Provincial Congress he helped organize and mobilize the provincial militia, and as captain of his town’s militia he led the response to the Lexington Alarm. Soon after, he was appointed major in the incipient Continental Army, and now he was second-in-command of a battalion engaged in the first major offensive of the Revolutionary War. Joining Bigelow on the Quebec expedition were a dozen other volunteers from Worcester. These included Jonas Hubbard, who had taken over as captain of Worcester’s militia when Bigelow was promoted, and John Pierce, a surveyor who kept a detailed journal of the expedition.[9]

When the Enos contingent turned back on October 24, Timothy Bigelow dispatched a letter to his wife Anna:

On that part of the Kennybeck called the Dead river, 95 miles above Norridgewock

Dear Wife. I am at this time well, but in a dangerous situation, as is the whole detachment of the Continental Army with me. We are in a wilderness nearly one hundred miles from any inhabitants, either French or English, and but about five days provisions on an average for the whole. We are this day sending back the most feeble and some that are sick. If the French are our enemies it will go hard with us, for we have no retreat left. In that case there will be no alternative between the sword and famine. May God in his infinite mercy protect you, my more than ever dear wife, and my dear children, Adieu, and ever believe me to be your most affectionate husband,

Timo. Bigelow[10]

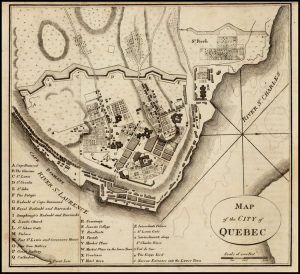

By the time Bigelow, Greenman, and the remaining members of expedition arrived at Quebec, only about half the original force was fit for duty, hardly enough to storm the walled city. Biding their time, Arnold and company awaited the arrival of the expedition coming from Lake Champlain, now commanded by Gen. Richard Montgomery. On their way to Quebec, Montgomery’s men had overrun Fort Saint-Jean and Montreal, and on December 1 they joined the Kennebec crew just west of Quebec, on the north bank of the St. Lawrence.

Days later the combined force tried to besiege to the city, but their own supplies were limited and time was not in their favor. Enlistments for most of Arnold’s men were due to expire at the end of the year; come spring, British reinforcements would likely arrive. But with smallpox ravishing the American camp, Montgomery and Arnold did not yet try to take the city. Meanwhile, Gov. Guy Carleton reinforced defenses along the city wall and trained several hundred sailors and militiamen to aid British Regulars.

Finally, on December 26, American officers gathered in council to discuss Montgomery’s plan of attack. A storm was brewing, and that could provide cover for a nighttime assault. Opinions differed, as reported by Worcester’s John Pierce:

Last night we had a general review and to day they are taking their names to see how many will scale the walls and how many will not &c. amongst our men there is great searchings of heart with respect to scaleing of walls and what the event will be God only knows — Its not my opinion to scale nor the opinions of my Capt [Jonas Hubbard] nor Lt. that’s well known and its not the opinion of Majr Bigelo neither.[11]

The men from Worcester, that hotbed of patriotism, were lining up on the side of caution—or perhaps cowardice, as some would say. Indeed, only two of Hubbard’s company “signed to scale the walls of Quebeck.” The others did not wish to risk their lives by charging a walled city perched on cliffs and defended by a fighting force now larger than their own.

Despite the opposition, eager voices prevailed, and Bigelow and Hubbard, against their better judgment, agreed to participate. The next day it stormed, right on cue, and the troops prepared for a nighttime attack. But then the weather cleared, causing postponement.

Two days later, when Timothy Bigelow was seen dodging one of the cannonballs British artillery fired into camp, he was “complained of for cowardice,” although anybody would be a fool not to get out of the way if he could. Word had gotten out: Bigelow was less than enthusiastic, and for this he was punished in the tribunal of public opinion within the military. When men rev up for battle, caution is not what they wish to hear.[12]

Was scaling the walls of Quebec really such a bright idea? That is not how British forces took Quebec from the French in 1759. James Wolfe never dared an assault on the city itself. As Fred Anderson wrote in Crucible of War: “To decide the issue, he [Wolfe] needed something that had never yet taken place in America, an open-field battle. Until Montcalm [the French commander] consented to give him one, he could do no more than shell the town, ravage the countryside, and issue bombastic proclamations calling on the French to surrender.”[13] It was on the Plains of Abraham, outside the walls, that British soldiers prevailed, enabling them to lay siege to the city; days later, the French surrendered.

Inspired by patriotism and perhaps enticed by dreams of glory, most of the men who had come all this way with Arnold or Montgomery vowed to take Quebec once again. But Bigelow and a handful of naysayers had good reason to doubt the wisdom of storming the city, even under cover of a storm. Mounting a wall is far more difficult than defending one. In fact, the Americans met defeat in the narrow streets of the lower town, without even getting a chance to mount the walls surrounding the upper town. Montgomery and some four dozen other Americans were killed; Arnold and some three dozen were wounded.

Private Jeremiah Greenman, Maj. Timothy Bigelow, and more than four hundred others were captured. While Greenman was fed “stinking salmond,” Bigelow and his fellow officers were feted with “a good dinner, and a plenty of several sorts of wine” on the very day of their capture. It was the finest meal they had enjoyed in months. While Greenman complained that he was confined to a “dismal hole” where “we live very uncomfertable for we have no room not a nuf to lay down to sleep,” Bigelow lived rather comfortably in Le Petit Seminaire de Quebec, where officers read, played cards, and exercised freely in the garden until their release the following summer.[14]

But Bigelow’s opposition to the assault continued to haunt him. After trudging through inhospitable country at the onset of winter and nearly perishing from hunger, he was labeled a coward for his realism and reproached for losing a battle he had advised against. John Lamb, leader of the artillery train, had the left side of his face blown off by grapeshot, causing blindness in one eye—and Lamb blamed his sad fate and the Patriots’ loss on Worcester’s hero, Timothy Bigelow. After he was paroled from prison, Bigelow ascended to the rank of colonel, commanded Massachusetts’s 15th Regiment, and proved his worth at Saratoga, Valley Forge, Monmouth, and the Battle of Rhode Island. Yet Lamb kept after Bigelow, and finally, on February 5, 1781, the two faced off in court. Bigelow stood before a five-member court of enquiry to defend his actions “in consequence of aspersions against his conduct on that day by Colonel Lamb.” Although the court concluded “that Colonel Bigelow’s conduct in the attack on Quebec the 31st of December 1775 is not reprehensible but that his behavior was consistent with the character of an officer,” he had paid a price by having to defend his name.[15]

Among Washington’s instructions to Arnold, before the expedition’s departure, was this:

If unforeseen Difficulties should arise or if the Weather shou’d become so severe as to render it hazardous to proceed in your own Judgment and that of your principal Officers (whom you are to consult), in that Case you are to return, giving me as early Notice as possible, that I may give you such Assistance as may be necessary.[16]

Arnold and his men had survived the weather, but their strategic disadvantage in Quebec might qualify as an “unforeseen difficulty.” The original idea was to invade with numbers that would overwhelm the few British soldiers defending the city. By the end of December, however, when American officers decided on a straight-on assault, the numbers had reversed: more men defended Quebec than were available to attack it, and the city had been fortified. Contrary to Arnold’s prediction, “Great numbers of the Canadians” had not rallied to the Americans (some did, but about as many joined the British). Common sense would suggest that scaling walls of a fortified city was not advisable in such a situation, yet American officers determined to press on, even though, in Washington’s words, their attempt might well “fail of Success.”

Why? Imagine the opposite: After traveling all that way, Arnold and Montgomery simply turned around and came home. No matter that Washington had given them free rein to do so. The rebuke poured on men like Timothy Bigelow would be greatly magnified. Officers would likely be dismissed, soldiers shunned and scorned.

Such is the logic of expeditions far afield, even if ill advised. It’s hard to say no, even when a “no” is called for. Judgment is clouded—hence, the “fog of war.” Quebec is a classic case. Little wonder that the first major offensive of the Revolutionary War receives so little play in our nation’s founding saga.

[1] American Archives, 2:976: http://amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A86445

[2] Washington to Schuyler, August 20, 1775, Founders Online: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0233

[3] Charles Royster, A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Army and American Character, 1775-1783 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979), 99.

[4] Royster, Revolutionary People at War, 23-24.

[5] Washington to Benedict Arnold, September 14, 1775, Founders Online: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0356

[6] The edition I cite here is Kenneth Roberts, ed., March to Quebec: Journals of the Members of Arnold’s Expedition (New York: Doubleday & Company, 1947). Used copies of cloth and paperback editions are readily available on the Internet. The “direful howling wilderness” quote, from the journal of Isaac Senter (p. 210) inspired the title of an excellent secondary account, Thomas Desjardin, Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold’s March to Quebec, 1775 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2007).

[7] Jeremiah Greenman, Diary of a Common Soldier in the American Revolution, 1775-1783, Robert C. Bray and Paul E. Bushnell, eds., (De Kalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1978). The Quebec expedition is on pages 13-35.

[8] Roberts, March to Quebec, 633.

[9] For more on Bigelow, see Ray Raphael, “Blacksmith Timothy Bigelow and the Massachusetts Revolution of 1774,” in Revolutionary Founders: Rebels, Radicals, and Reformers in the Making of the Nation, Alfred F. Young, Gary B. Nash, and Ray Raphael, eds., (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011, 35-52.

[10] Patricia Bigelow, Bigelow Family Genealogy (Flint, MI, 1986), 1:78, quoted in Desjardin, Howling Wilderness, 82.

[11] Roberts, March to Quebec, 701. For more on those who were reticent, including other names, see pages 231, 374, and 429.

[12] Roberts, March to Quebec, 702. Capt. Simeon Thayer reported the pressures exerted on men who evidenced a disinclination to fight: “Dec. 28. Some of the soldiers took 4 men that refus’d to turn out, and led them from place to place with halters round their necks, exposing them to the ridicule of the soldiers, as a punishment due to their effeminate courage.” (Roberts, March to Quebec, 273-274.)

[13] Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000), 349.

[14] Greenman, Diary, 24; Roberts, March to Quebec, 154, 157.

[15] George Washington to Henry Knox, July, 28, 1780, and George Washington, General Orders, February 18, 1781, in Writings of George Washington, John Fitzpatrick, ed., (Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1939), 19:275 and 21:241. Founders Online: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-04894

[16] Washington to Benedict Arnold, September 14, 1775. Founders Online: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0356

One thought on “March to Quebec and the Fog of War”

Mark R. Anderson’s The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony: America’s War of Liberation in Canada, 1774-1776 (UPNE, 2013) is an exhaustively researched and well written account of this particular time period. He identifies not only the expiration of militia terms as a reason to push ahead with the assault, as Ray does in this article, but also the need to quickly demonstrate to sympathetic Canadians the rebels’ ability to establish control over the colony by taking its capital.

Much rode on this political aspect of things in hopes of turning the majority of Canadians waiting in the wings over to the American side. Otherwise, without these two compelling factors pushing him, Montgomery would have been happy to continue the blockade for the immediate future in hopes of starving out the garrison. (191)

Another issue driving the decision to attack sooner than later concerned the discord breaking out among Arnold’s three commanders. (193) Verging on mutiny, Montgomery succeeded in quelling them and gaining their consent to work together in attacking the walled city. However, an additional obstacle presented itself when a soldier with knowledge of the plans deserted to the British and told them what was about to happen. Montgomery then sought to alter his attack, but, as it turned out, it was too rushed, too little, and too late.