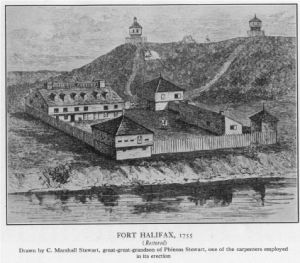

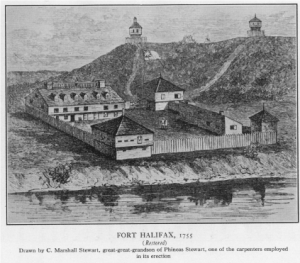

Massachusetts Provincial Troops built Fort Halifax in 1754 on the site of an ancient Indian encampment and village site. The location of the fort proved critical. It sat along a transportation crossroads at the confluence of the Sebasticook and Kennebec rivers. Further up the Kennebec was a series of rapids and waterfalls. The Fort protected the New England frontier from French and Indian incursions and served as a trading post. An eight hundred foot-long palisade enclosed several buildings: a row of barracks and the two-storied “fort house” containing officers’ quarters, storerooms, and the armory. Two-story, hip-roofed blockhouses stood on the southern and northern flanks. Each had square-hewn timbers, dovetailed at the corners, with a pyramid-shaped hip roof, and tiny windows with loopholes for firing. A log sentry box was on another corner. High on the rocky hills above the fort were two smaller guard towers. Though the fort never came under direct attack, it had ample defenses: several artillery pieces, including a twelve-pounder howitzer, a two-pounder, and swivel guns. Two trained bulldogs guarded the gates.[2] The fort’s construction crew included eighteen year-old Enoch Poor.[3] Poor later became a brigadier general and distinguished himself at Saratoga, in the Battle of Monmouth, and in the Sullivan Expedition against the Iroquois Indians. The Plymouth Company, a group of Massachusetts investors, also built Fort Cushnoc (Fort Western) in 1754. Located in present-day Augusta, Fort Western was a base from which to supply Fort Halifax.[4]

In the late-1760s, Massachusetts withdrew its troops. It sold Fort Halifax in 1770 to Boston physician, merchant, and land investor Dr. Silvester Gardiner. Gardiner then leased the property, which consisted of the blockhouses and a tavern in the former officers’ barracks.[5]

When Arnold’s first troops arrived on their journey to Quebec, the fort had begun to deteriorate. An advance party of Pennsylvanians under Lieutenant Archibald Steele reached Fort Halifax on September 23. Private John Joseph Henry wrote in his journal that the Fort “consisted of old Block-houses and a stockade in a ruinous state” and “did not admit of much comfort; besides it was inhabited…by a rank tory.” Henry and the soldiers lodged in a private residence nearby. They enjoyed “agreeable” conversation and learned of the decline of the area deer population. The next morning, the soldiers returned to the fort and met the tory, Ephraim Ballard, “who claimed the right of thinking for himself.” Ballard, a surveyor, tenant, and caretaker for the property, traded them a barrel of smoked salmon for a barrel of pork, “upon honest terms” and they proceeded upriver.[6]

As Henry and the Pennsylvanians scouted ahead, the bulk of Arnold’s army left Fort Western for Fort Halifax. Some traveled by bateaux. Others walked some, or all, of the rough road on the east bank of the Kennebec that led from Augusta to Winslow. They reached the fort from September 26-October 1, 1775. Arnold’s letters say nothing about Fort Halifax. Major Return J. Meigs of Connecticut saw “two large block-houses, and a large barrack [the tavern], which is enclosed with a picket fort.” As Dr. Isaac Senter put it, “This appeared a very pleasant prospect.” But the prospects for the expedition looked grim. Boats were damaged and men were sick. Senter’s bateaux arrived “in such a shattered condition” that he had to purchase another. And, he noted, “several of our army were much troubled with the dysentery, diarrhea, &c.” These were ominous signs of the hardship to come.[7]

The men, 1,100 in all from New England, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, arrived in waves and gathered at Fort Halifax before they began the arduous task of hauling their canoes around or over the waterfalls and rapids up the Kennebec River. Officers secured private accommodations in the sparsely populated countryside. Enlisted soldiers camped outside the fort or across the Sebasticook River. Many of the soldiers who reached Fort Halifax later attained prominence. Henry Dearborn fought at Ticonderoga, Freeman’s Farm, Saratoga, and Monmouth, and served as Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of War. Daniel Morgan and his riflemen later earned acclaim at the Battle of Cowpens. Indian guides paddled Arnold in a birch bark canoe. Traveling with Dr. Senter was Nathanael Green’s brother, Christopher Greene. He later defended Fort Mercer in New Jersey against a Hessian attack and led a regiment of African American and Native American troops. And one of several gentleman volunteers was nineteen year-old Aaron Burr, who became a lawyer, politician, duelist, alleged traitor, and womanizer. [8]

In 1852, a Winslow resident recalled that in 1775, Burr, who later gained a reputation as a lothario for his playboy ways, visited “Fort House” tavern, located inside the fort. “A great many times,” her father, the tavern-keeper, and formerly the ensign at Fort Halifax, told his guests a memorable story. Much to the chagrin of “an Indian maiden” Burr had already seduced, the young gentleman “made love to the fair Sarah Lithgow,” the daughter of the fort’s former commander. The soldier reportedly wrote sonnets “on the bark of the silver birch” that grew by Taconic Falls. He sent the poems to her by his servant. Burr’s advances went unrequited: “She would have nothing to do with him.” While the tale, and several similar versions of it that appear in the historical record, may not be true, the visit of Burr and of Arnold’s army is one memorable episode in the rich history of Fort Halifax.[9]

It was not the last activity at the fort during the Revolutionary years. In 1776, the local Committee of Safety chased the tory Ephraim Ballard out of town. Massachusetts confiscated Gardiner’s property. In 1779, Massachusetts set up a truck-house (trading post) to supply and protect Penobscot Indians who had allied with the Patriot cause and who had been driven from their lands by the British. Chief Joseph Orono and about thirty Indians temporarily settled near the fort. Their priest briefly lived at Fort Halifax. Fort Halifax also served as a staging area for an ill-fated Patriot attack on British defenses in Maine’s Penobscot Bay later that year. When the expedition turned into a debacle for the invaders, the fort offered refuge and respite for retreating troops.[10]

At the end of the Revolutionary War, most of Fort Halifax fort was dismantled. What remained on the site, a nineteenth century historian wrote, served as a dwelling house, and hosted “a Church, dancing and amusement parties, trading house, tavern, town house, and finally, began to be occupied by poor families.” By the early 1800s, only the blockhouse on the southern flank still stood.[11] Later in the century, tourists visited the fort, especially railway passengers traveling from Boston to Bangor and Colby College students from the neighboring town of Waterville. These guests gouged pieces of wood from the blockhouse as souvenirs.[12] In the nineteenth and twentieth century, ownership of the structure passed hands numerous times. Fort Halifax blockhouse became a National Historic Landmark, the oldest original blockhouse in America from the French and Indian War era.[13]

Although a catastrophic flood in April 1987 carried much of the blockhouse down the Kennebec River, carpenters rebuilt it the following year. It still stands as a little known tourist attraction within a picturesque public park. Today, Fort Halifax Park greets picnickers, sport fishermen, kayakers, and history buffs. A few years ago, it even hosted a wayward harbor seal. The Town of Winslow’s Parks and Recreation Department occasionally opens the blockhouse to the public. Like Arnold’s Expedition in 1775 or the reenactment in 1975, each July 4 the site at the confluence of the Kennebec and Sebasticook rivers comes alive when Winslow celebrates Independence Day with a festival at the site. The town plans to rebuild some of the fort and to expand and improve interpretive displays, trails, and recreational opportunities at the site in the hopes that future generations can better understand and enjoy the history and setting of Fort Halifax.[14]

Figure 1: A view of the Rivers Kenebec and Chaudiere, with Colonel Arnold’s route to Quebec (London: R. Baldwin, 1776). Courtesy Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library.

Figure 2: Colonel Arnold who commanded the Provincial Troops sent against Quebec…by Thos. Hart, 1776. Anne S. K. Brown Collection, Brown University.

Figure 3: Aaron Burr (attributed to Gilbert Stuart), ca. 1794. New Jersey Historical Society.

Figure 4: Recreation of One of Arnold’s Boats. Steve Sheinkin Photo, 2012.

Figure 5: Fort Halifax, 1755, from Collections of the Maine Historical Society, VIII.

Figure 6: Fort Halifax Park Welcome Sign. David Thomas photo, 2013.

Figure 7: The Blockhouse at Fort Halifax. David Thomas photo, 2013.

Figure 8: The Blockhouse at Fort Halifax. David Thomas Photo, 2013.

Figure 9: Construction of Fort Halifax. David Thomas Photo, 2013.

Figure 10: The Blockhouse at Fort Halifax, from Inside the Imprint of the Fort. David Thomas photo, 2013.

[1] The Colby Echo, 2 October 1975.

[2] National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Fort Halifax Blockhouse,” 1979, http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NHLS/Text/68000015.pdf, accessed 13 June 2013; Carleton Edward Fisher, History of Fort Halifax (Winthrop, ME: Courier-Gazette, 1972); T.O. Paine, “Historical Sketch. An Inquiry into the History of Fort Halifax.” The Eastern Mail [Waterville, Me.], 4 November 1852.

[3] Journal of the Honourable House of Representatives…Massachusetts-Bay…1755 (Boston, 1755), 29.

[4] “Welcome to Old Fort Western,” http://www.oldfortwestern.org/, accessed 13 June 2013.

[5] Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812 (New York: Vintage, 1990), 14, 16, 369-70.

[6] John Joseph Henry, Account of Arnold’s campaign against Quebec, and of the hardships and Sufferings of that Band of Heroes…(Albany: Joel Munsell, 1877), 16, 18; Thomas Desjardins, Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold’s March to Quebec, 1775 (New York: St. Martin’s), 55-57.

[7] The Journal of Isaac Senter (Philadelphia: Published by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1846), 15-16; Return J. Meigs, Journal of the Expedition against Quebec under Command of Col. Benedict Arnold, in the Year 1775 (New York: Privately Printed, 1864), 11.

[8] Stephen Darley, Voices from a Wilderness Expedition: The Journals and Men of Benedict Arnold’s Expedition to Quebec in 1775 (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2011), 104, 105, 127, 134, 153; Arnold Expedition Historical Society, http://arnoldsmarch.com/research.html, accessed 13 June 2013.

[9] T.O. Paine, “Historical Sketch. An Inquiry into the History of Fort Halifax.” The Eastern Mail, 25 November 1852; Hope Braley Horne, Winslow: Our Town, Our People (Winslow, Me.: H.B. Horne, 1991), 87.

[10] Ulrich, A Midwife’s Tale, 14, 16, 369-70; Pauleena MacDougall, The Penobscot Dance of Resistance (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2004), 104-5; Portland Daily Press, 1 March 1882.

[11] Maine Historical Society Collections, Vol. VIII, 277-78; Paine, “Historical Sketch,” 25 November 1852.

[12] The Colby Echo, 29 April 1893; Portland Daily Press, 19 May 1871.

[13] “National Historic Landmarks Program,” http://tps.cr.nps.gov/nhl/detail.cfm?ResourceId=772&ResourceType=Building, accessed 13 June 2013; Deed for Fort Halifax, from Daughters of the American Revolution to State of Maine (1966), Kennebec County Registry of Deeds, Book 1408, 369. http://winslowhistory.weebly.com/uploads/9/1/6/5/9165582/fort_deed_to_state.pdf, accessed 13 June 2013. For historic images, see “Fort Halifax,” http://winslowhistory.weebly.com/fort-halifax.html, accessed 13 June 2013.

[14] Fort Halifax Park Concept Master Plan. June 2011. http://www.winslow-me.gov/content/1359149616fort-halifax-park-adopted-plan-07-11-2011-web2.pdf, accessed 13 June 2013.

One thought on “Fort Halifax: One Stop on the Way to Quebec”

Very interesting article. My father Neil was born in 1909 (my mother Dorothy Higgins graduated from Colby) and during the flood of ’87 had told the local authorities to chain down the fort because it was going to go under. They told him, “no the water will never reach this high”. He was so correct. I have a great many things including pictures. He kept scrape books etc.