William Mehls Dewees (1711-1777)

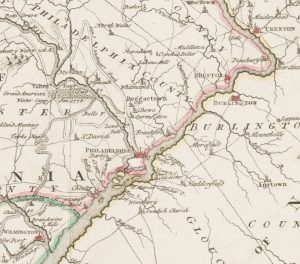

The “Father” of this history is William M. Dewees. He was the son of William Dewees of Germantown (1680-1745), “the papermaker,” and Anna Christina (Mehls) Dewees (1690-1749).He was born at the new family home and paper mill in what is now Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia. In 1735, he married Rachel Farmar (1712-1777), the daughter of Edward Farmar (1672-1745), the youngest son and heir to the vast Farmar land holdings.[1] In 1704, those lands became Whitemarsh Township of Philadelphia County. In about 1710, Edward Farmar built his family home and mill, and donated land to build a church on a portion of those lands.[2]

After their marriage in “the little church at Whitmarsh,” the couple lived on Farmar land. William M. was serving his father-in-law by selling plantations of the Farmar lands. Soon their first child, and the “Son” of this story, William Farmar Dewees (c. 1739-?) was born.

When William the papermaker died in 1745, he left his son William M. Dewees a token five shillings. When Edward Farmer died the same year, Rachel inherited “Some lands [that] cannot be sold until the leases have been expired.”[3] The executor, Peter Robeson, a brother-in-law of Rachel, insured that, when distributing Farmar land to family, there were “18 ¼ acres exempted granted . . . to William DeWees, inn holder of Germantown.”[4]

On February 3, 1747, a notice in The Pennsylvania Gazette advertised that a “commodious stone house” in Germantown was “To be SOLD.” William M. was in possession.[5] It was the original Dewees family home, his inheritance.

William M. had inherited land and ready money. He began establishing the financial and social foundations of family life. In 1750, he had warrants on three plots of land totaling 450 acres.[6] In 1751, he placed his youngest son, Farmar, in the new Philadelphia Academy. He would be educated along with the scions of the Philadelphia elite.

Once financially and socially secure, William M. began contemplating life as a public official. To do that, he could rely on another family.

Since their arrival in Germantown, the Dewees and Potts families had remained close.[7] William Dewees (1680-1745) was active in establishing paper mills and churches.[8] Thomas Potts Jr. (1680-1752), acquired iron furnaces and forges.[9] They served as town officials together. William M. and the Potts boys, John (1709/10-1768) and Thomas (1720-1762) were contemporaries in the small town.

John Potts joined his father to build the largest iron production and distribution empire in colonial America.[10] At his father’s death in 1752, he inherited much of that empire and became the family patriarch controlling the business. He acquired a large plantation on the Schuylkill River, laid it out as a village and built himself a mansion named “Pottsgrove.” Other family members built homes and established businesses there.[11] At this time, John Potts also acquired the Mt. Joy Forge. It was located about fifteen miles down the river from Pottsgrove, on Valley Creek. It was known locally as “the valley forge.” The works consisted of a forge, sawmill and stone house. John added a grist mill.[12] He soon was appointed justice of the peace for that area of the county.

In 1757, William M. was appointed justice of the peace for the Whitemarsh area of Philadelphia County. Justices of the peace were the senior public officials in their home area. Collectively, they sat as the Justices of the Courts of Common Pleas, Quarter Sessions of the Peace and Orphans Courts of the City and County of Philadelphia. Thus, William M. Dewees and John Potts often worked together. The justices also performed a wide variety of other public duties.[13] This position made William M. a well-known and busy man, which built his reputation. He was known as “William Dewees, Esq.”

John Potts’ younger half-brother, now known as Thomas Potts, Jr. (1720-1762), had inherited substantial portions of the Potts iron empire.[14] When he died, his executors included one of “my beloved frends” “William Dewees sener of White Marsh, Esq.” His holdings in the ironmaking empire passed to his large family. His daughter by his first wife, Sarah Rutter Potts (1745-1767), received the proceeds from the sale of his substantial Philadelphia property. The next year, William M.’s son, William F., married Sarah Potts.[15]

These connections with the Potts family determined the roles that William M. and his son William F. would play in the Revolution. In 1773, William M. was elected High Sheriff of Philadelphia. William F. became the co-owner of the Mount Joy Forge.

William M. Dewees, High Sheriff of Philadelphia

In 1764, William built a mansion for Rachel and their younger children. It was on the Farmar land that he had inherited adjacent to St. Thomas Church, Whitemarsh. He had the initials D above W&R carved on the gable end.[16] Soon, his aspirations and the Potts family pushed him to a higher level.

In 1769, William M. bought property in the City of Philadelphia’s Mulberry Ward; by 1771 he had a home there and Rachel joined him.[17] In 1773, he ran a notice in the Pennsylvania Gazette soliciting votes for election as Sheriff of Philadelphia County.[18] In the election that year, he was one of two individuals receiving the most votes for sheriff. He was the one selected and commissioned by the governor on October 4.[19] He did the same again in 1774 and was reappointed. His appointment was reaffirmed, after being exonerated of a complaint against him.[20] In 1775, he thanked the voters for their past support and solicited support for his “third and last year.” He was elected and appointed by the governor.[21]

The Sheriff was the chief law enforcement officer for the city and county of Philadelphia. As such, he was responsible for enforcing criminal law by supervising the constables and night watch. He accepted their prisoners, investigated and determined their crimes, and presented the prisoners to the courts. He was also the senior officer of the courts, enforcing civil law by taking bail, supervising the constables in conveying prisoners to and from confinement, directing the constables in the serving of writs and summonses, supervising elections and retaining possession of the ballots, and holding sheriff’s sales.[22]

William M. Dewees’s period of elected service, from 1773 through 1776, was during the height of the pre-Revolutionary era, tumultuous times of growing civic opposition to both the British parliamentary and Penn proprietary governments. Committees of Inspection and Investigation, formed with the encouragement of the first Continental Congress, had been taken over by the city’s most radical anti-Parliament figures. They began exercising some law enforcement, judgement and punishment functions in parallel to the established governmental system.[23] William M. had to deal with confrontations, arrests, and judicial decrees against citizens and businesses by a number of organizations. Their aggressive efforts ensured that the interactions sometimes turned violent and involved calls for the help of constables.[24] Finally, a Committee of Safety was created and given broad discretionary powers overseeing and directing activities for defense and public safety.[25] That made the local responsibilities and authority of the sheriff much clearer.

A greater problem for Sheriff Dewees had national implications. Philadelphia was the seat of both the Pennsylvania Assembly and the Continental Congress. It became the venue for political turmoil and mass meetings to pressure those bodies to move toward independence.[26]

By long tradition and common law, the sheriff had the power of posse comitatus, the “power of ordering to the sheriff’s assistance the whole strength of the county in order to suppress unlawful force and resistance.”[27] This gave Sheriff Dewees the authority to call upon constables to maintain crowd control during large public gatherings. Thus, William M. and the constables were present at the Pennsylvania State House during some historic events:

• The December 1773 “Philadelphia Tea Party,” when 8,000 people gathered contemplating a tarring and feathering.[28]

• June 1774 mass meetings when several thousand assembled to form the Pennsylvania Committee of Correspondence.[29]

• November 1774, when a “respectable number of inhabitants” assembled and formed Committees of Observation and Inspection to monitor and enforce the Continental Association.[30]

• April 1775, after news of Lexington and Concord, when nearly 8,000 people gathered, many with arms.[31]

• May 6, 1776, when Sheriff Dewees closed polls early and radicals did not get assembly representation in Philadelphia.[32]

• May 20, 1776 when, with the encouragement of John Adams, 4,000 people gathered in the rain to pressure Pennsylvania’s congressional delegates to vote for independence.[33]

Having stood by and watched while history was being made, William M. had his chance to participate in the final event. On July 6, 1776, the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety directed: “the Sheriff of Philad’a read or Cause to be read and proclaimed . . . the Declaration of the Representatives of the United Colonies of America”[34]

On July 8, Sheriff Dewees led a procession of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, Committee of Observation and Inspectionand assembled notables to a crude platform near the Pennsylvania State House.[35] There he called out; “Under the authority of the Continental Congress and by order of the Committee of Safety, I proclaim a declaration of independence.” The Declaration was then read to the assembled crowd by Col. John Nixon of the Committee of Safety.[36]

William F. Dewees of Valley Forge

William F. Deweesand Sarah moved to Pottsgrove and he became integrated into the Potts family business. Sarah died in 1767, and in 1769 he married Rachel Waters (1748-1822).She was the daughter of prosperous Tredyffrin citizen Thomas Waters (1719-1795). The township lay just southeast of the Mount Joy Forge, by then owned by Joseph Potts (1744-1804).

In 1773, Potts transferred to William F. and David Potts (1743-1797), his brother, each half interest in Valley Forge.[37] At about the same time, Isaac Potts (1750-1798), another brother, became owner of the grist mill and built himself a stone residence on the property.He rented the grist mill to William F. and used his house as a vacation-rental home. William F. was the co-owner and became the resident general manager of the entire industrial complex at Valley Forge.[38]

William F. was a patriot. By August 1776, his forge was producing gun barrel blanks and other war-related material for the Continental army.[39] He was concerned about the security of the French Creek Powder Works nearby. He wrote to the council of safety a long letter, concluding: “I think you will not have much assistance from the [Associators, a volunteer, locally supported] militia in these parts . . . The men and officers utterly refused going some of whom I had advanced money to out of my own pocket.”[40]

In March 1777, the Pennsylvania Assembly established a militia. William F. was appointed district sub-lieutenant of militia administration for Tredyffrin, Schuylkill, and East Pikeland Townships of Chester County. His position gave him the honorary title of lieutenant colonel, but did not confer military authority.[41] He had to write to the council of safety requesting that a “Serjeants Guard of Militia [be] stationed at Valley Forge.”[42] No guard seems to have been posted. When he was at the French Creek Powder Works, trying to get militia posted there, an explosion and fire occurred. The owner suspected sabotage.[43] William was called to testify in the investigation.[44]

Also in March, Thomas Mifflin, the quartermaster general of the Continental Army, visited Valley Forge and told William F. that “he was establishing a Magazine of Continental Stores” and considered his property “as most suitable for that purposes.” William F. was reluctant and asked for “a few Days to consider whether [storing the goods] might not be a means of drawing the British Army that Way and endanger his Property.” Mifflin reassured him of “a strong Defense or otherwise the stores would be timely removed.” The next day fourteen teams loaded with stores arrived. William F. went to Philadelphia and acquainted the Commissary General “with the danger” of storing supplies at Valley Forge. He was told that General Washington had ordered the move.[45] That was the end of the matter. In April, he was one of a number of individuals requested to provide 100 wagons for use in removing the public stores from Philadelphia.[46]

The Battle of Brandywine occurred on September 11. William F. hurriedly moved his family to his father-in-law’s home in Tredyffrin. Mrs. Woodford, who lived nearby on Gulph Road, later claimed that,

Colonel William Dewees’ wife, had brought some trunks over to the house . . . [saying] that they were personal possessions and if the British came down to the Forge they would lose them. . . . It turned out that Dewees’ uniform was in there along with his sword and other military regalia. When [Mrs. Woodford] afterward found out, she took the trunks and threw them into a quarry[47]

General Howe turned his army eastward toward the Schuylkill crossings and Philadelphia. Colonel Clement Biddle, the Continental Army Forage Master, was removing supplies out of the way of the advancing British army. On the night of September 16, he stopped at Valley Forge. William F. was there and provided him with a signed inventory of stores. Biddle sent it to General Washington.[48]

In response to William F.’s report, Washington ordered his aide, Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton and Capt. “Lighthorse Harry” Lee to remove or destroy the supplies. They arrived at Valley Forge on the morning of September 18. William F. was there to help. Howe’s army was camped less than five miles away at Tredyffrin; an informant had reported military supplies at Valley Forge. In response, a force of dragoons and light infantry was ordered there on the morning of September 18. The stage was set for the “Battle of Valley Forge.”

Hamilton came from Washington’s headquarters and Lee arrived with six mounted dragoons. They arrived at Valley Forge on the morning of September 18. Hamilton described taking possession of two barge-like boats that could “convey fifty men.” Lee said that included a flat- bottomed boat “should the sudden approach of the enemy render such a retreat necessary.” To warn of that approach, Lee posted two mounted men as sentries on Mt. Joy, overlooking Valley Creek and the forge. Both precautions proved sound.

As the British approached, Lee’s sentries fired warning shots and rode down the hill pursued by British dragoons firing. Hamilton, and those with him, boarded the boat and pushed off. The British fired on the boat. Hamilton lost his horse, one civilian boatman was killed and another wounded. Hamilton jumped into the river and swam ashore. Lee and his men escaped on horseback across a nearby bridge, with the British close behind firing. William F. barely escaped with his life.[49]

On the 19th, the British sent two units of light infantry and grenadiers to Valley Forge. Major An American officer on reconnaissance at the top of Mount Joy witnessed a

huge conflagration along Valley Creek that lit up the slopes of Mount Joy illuminating the rushing waters of the Schuylkill and filling the valley with embers and smoke . . . Streams of golden sparks shot high into the starlit night as the billowing flames silhouetted the last of his majesty’s troops.[50]

According to William F. Dewees, the British destroyed and burned the forge, sawmill, associated buildings and his residence. They confiscated much of his property, grain, livestock and personal belongings.[51] Neither Isaac Potts’ home nor his grist mill were destroyed.

General Howe moved his army into camp at Tredyffrin. Many homes, including William F.’s, were ransacked and much property was stolen.[52]

Just ahead of them, William F. had moved his family to the home of his aunt Christina (Dewees) Antes and his cousin Col. Frederick Antes, across the Schuylkill in Frederick Township. The colonel was away, commanding a militia unit at Swedes Ford. The British crossed at Fatland Ford, just to his north, on the 22nd. Colonel Antes returned just in time to welcome General Washington to his home on September 23.[53]

Washington stayed until September 26. This was William F.’s first meeting with Washington, who appears to have suggested things William F. might do.

Sheriff William M. Dewees’s Last Days

William M. Dewee’s elected service as Sheriff ended in the fall of 1776. In the election of November 1776, William Masters won, defeating James Claypoole. Masters declined to serve. Claypoole was not commissioned until June 1777.[54] While the office was officially vacant, William M. continued to serve and was still on the job as the British approached.

A young army fifer, who had returned to Philadelphia after Brandywine, met him. He later wrote:

On our day previous to leaving Philadelphia, I was out taking a walk around the city . . . I espied some fine looking cabbage in a back lot . . . I had just pulled up a head . . . Whilst in this position I was surprised and taken prisoner by a “strapping big” negro, . . . The negro took me into the house . . . There happened to be some company with the man of the house that night . . . the negro . . . catching me as he did, created some fine sport for them. The gentleman of the house asked me my name. I told him it was Samuel Dewees. Samuel Dewees (said he). Yes, sir, was my reply . . . He then asked me where my father lived. I told him that he lived in Reading. He then asked me what my father’s name was. I told him that it was Samuel Dewees. He then asked me what business my father followed. I answered by trade that he was a Leather Breeches maker. By these answers to his interrogations, he found that he and I were second cousins, his father’s, father and my father’s, father [Cornelius Dewees, 1682-?] having been brothers. This man’s name was William Dewees who was then the High Sheriff of Philadelphia County. . . . I was very glad, however to get off as I did, . . . the British taking Philadelphia in a few days thereafter, September 26, 1777, we were forced to fly from the barracks.[55]

As General Cornwallis marched into Philadelphia, William M. was captured and confined. Hopefully, he was kept with captured officers in the State House. There, “their Bedding & blankets were greatly deficient, that they had Sent in a Petition to Genl Howe relative to their Provisions & firing to Which they hoped An Answer but had not Recd it.”

If he had the misfortune to be held in the Walnut St. Prison with common soldiers, “their Sufferings Are Very great. Many of them already Naked, with Very little Bedding & blankets. Their Allowance of Provisions by no means Sufficient, with Very little firing.”[56]

In such miserable circumstances, William M. died at age sixty-six. He was likely buried along with many other prisoners in nearby Potter’s Field.[57]

William F. In Service to George Washington

In early October William F. set off for Philadelphia with a neighbor, Joseph Cloyd, a captain of the militia. After leaving Tredyffrin, they had only gotten as far as Ridge Pike and turned south toward the city when they were captured. They were sent to Philadelphia and held until November 14. During that time, Cloyd testified and William F. affirmed that:

they were confined in the General Guard . . . three days & an half without a Morsel of any kind of Provision, from thence they were removed to the new Gaol [Walnut St. Prison] where they had liberty to walk in the yard – that during the first Six days of their Captivity [there] he did not receive one mouthful of Provision, but what was brought by his Wife who come into the City on the Fourth day. On the Sixth day of that imprisonment, they drew three biscuit & about One-Quarter of a pound of Pork-they did not draw again until five days after when they again drew . . . about enough to serve a man for a meal-they then removed to the old Gaol [Stone Prison], where they remained so long as to make up three Weeks in the whole

Finally, Cloyd’s wife,

not being able to get any Provisions [went] to Joseph Galloway, Esq in order to get their discharge to prevent their starving—the answer was that unless they would take the oath of allegiance they must remain.

They took the oath and were discharged.[58]

On November 14, General Washington added a postscript to a letter to General Howe concerning the exchange of prisoners:

P.S. Just as I was about to close my Letter. Two persons Men of Reputation came from Philadelphia. I transmit you their Depositions respecting the treatment they received while they were your prisoners. I will not comment upon the subject. It is too painful.[59]

In November, William F. named his new-born son George Washington Dewees (1777-1834).

Washington’s army settled in a defensive line in the hills at Whitemarsh.[60] General Howe was wary that Washington might attack before winter. To preclude that, he decided to take the initiative.

Washington had good intelligence on enemy intentions.[61] Sometime on Thursday, December 4, William F. added to this when he wrote to Washington:

I Have Just Recd Information which I Beleive to be the Best Can be Obtaind that the British Army had Last Night Packd up all their Baggage & each Man four Days Provision Coock’d; their Horses hitchd to their Artillery & every Appearance of marching out Immediately. But something happening which is Not accounted for the orders were Countermanded; the Reason Assignd to me is they Expect our army to move their Camp very soon as they Have Recievd such Information and think they will Do Better to attack when your army moves as they have heard you are advantagiously Posted; But it is Expected they are Determind to Attack you where you Now Are; on Saturday morning Next I Expect I shall be Able to Inform you Exactly when they will Attack for Beyound all Doubt they are Determind to Attack at all Events[62]

This report was specific and accurate. His source must have been someone with access to the British and someone he trusted. It could have been his brother Thomas, the former jailer of Philadelphia. He had been captured and, in fear for his life, had unsuccessfully offered his services and taken the oath of allegiance.[63] He remained in the city.

As William F. had informed Washington, the British march out of Philadelphia was planned for the morning of December 4, but was delayed until later that day. Thanks to William F. and others, Washington was ready. The battle was inconclusive, and Howe returned to Philadelphia.

Washington had to decide where to place his army for the winter. He chose Valley Forge. There is no evidence that William F. suggested it. Others did.[64]

The force arriving at Valley Forge consisted of some 19,000 officers and soldiers. The first order of business for the soldiers was to build about 2,000 huts. In building these, the army deprived William F. of “the greatest part of his standing Timber and all of his fences.”[65] The remains of his buildings destroyed by the British were tempting sources to be ransacked for other building materials. Washington attempted to prevent that in his general orders of January 6, 1777.

Colo Dewees who was nearly ruined by the Enemy Complains that the remains of his buildings are likely to be destroyed by this Army. The Commander in Chief positively forbids the least injury to be done to the walls and chimnies of Colo Dewees buildings; and as divers Iron plates have been taken from them the Commanding Officers of Corps are immediately to inspect the huts of their regiments, and make return to the Quarter Master Genl. All they can find and the names of the Persons in whose possession they are found that they may be restored when demanded.[66]

The army settled in. Washington and his staff could begin to relax a bit. Washington took over Isaac Potts’ house. It was rented to Mrs. Deborah Hewes, a step-in-law of both Isaac Potts and William F.[67] She departed for Pottsgrove and Washington moved in on Christmas Eve. Mrs. Washington joined him in February 1778 and stayed until June.

William F. was living nearby at Tredyffrin.[68] There were “many instances . . . of intercourse of this family with the General and his wife, during the terrible winter of 1777.”[69]. During one of his visits, for business or pleasure, William F. offered his forge house for use as the encampment “bake house.”[70]

Washington and his army left Valley Forge in June 1778, leaving the area ravaged. William F. did not return. His part-ownership of Valley Forge was foreclosed and bought by Isaac Potts. William went into bankruptcy. The date of his death and place of burial are unknown. It is generally believed that he died in ill-health and poverty sometime between 1794 and 1809. His family did not receive compensation for the damage done to Valley Forge by the British until 1818.[71]

This story of Dewees, Father and Son, presents a very real example of the sacrifices those tremulous times of our Nation’s beginnings required of the average citizen.[72].

[1]The Dewees genealogy and family history are recorded in “Family of Gerrit Hendricks de Wees,” wilsonfamilytreealbumblog.wordpress.com/family-pages/garrett-hendricks-de-wees/and “Family of Wilhelm de Wees (1680),”wilsonfamilytreealbumblog.wordpress.com/family-pages/family-of-wilhelm-de-wees-1680/. Also, Ellwood Roberts, ed.,Mrs. Philip E. La Munyan, The Dewees Family: Genealogical Data, Biographical Facts, Historical Information(Norristown, PA: William H. Roberts, 1905). The history of the Farmar family is summarized in “History of Whitemarsh Township, whitemarshtwp.org/229/History. Also, Phillip Alan Farmar, Edward Farmar and the Sons of Whitemarsh (Shawnee, OK: Tiki Publishing, 2018).

[2]The remains of his mill are on the National Register of Historic Places. It was once part of the Pennsylvania Historic site of Hope Lodge, but has been returned to private ownership.

[3]Farmer to DeWees. Rachel, wife of William DeWees, Esq. Phila. Co., Deed Bk. G 12, 343.

[4]Will of Edward Farmar. FHL21723 – Will Book H, 71-74 – Will date July 18, 1745; Codicil August 22, 1745, Probate September 19, 1745. Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania Deed Book G-9, 458.

[5]“To be Sold,” Pennsylvania Gazette, Friday, February 3, 1747.

[6]On March 4, 1750 he had warrants on plots of 100 acres, 100 acres, and 250 acres, likely parcels from the Farmar inheritances. “William Dewees,” Pennsylvania, U.S., Land Warrants and Applications, 1733-1952, Ancestry.com, ancestry.com/search/collections/2350/?name=William_Dewees&event=-3_1750&count=50.

[7]Thomas Potts Sr. (1647-1726) and family settled in Bristol Township, near Germantown in about 1690. Gerrit Hendricks Dewees (1641-1701) and family also arrived in 1690.Both families’ land bordered on land of one of the original Germantown families, Keurlis.

[8]In addition to being a papermaker, William assisted arriving immigrants to form into congregations of various European reformers (Luther, Menno Simons, Calvin). He then united some of those congregations into one formal “Reformed Church.” That church is credited as the founding church of the United Churches of Christ as well as other smaller reformed denominations in America. United Church of Christ, ucc.org/about-us_short-course_the-german-reformed-church/.

[9]Thomas Potts Jr. was the nephew and ward, or foster son, of Thomas Potts Sr. He married Martha Keurlis. He went to the Manatawny area to work in the iron works of Thomas Rutter. When Rutter died in 1728-1729, Thomas Jr. became principal owner and manager of the iron works. Mrs. Thomas Potts James, Memorial Thomas Potts, Junior Who Settled in Pennsylvania; Historic-Genealogical Account of his Descendants to the Eighth Generation (Cambridge, MA: Privately Printed, 1874), 73-88.

[10]For a cogent description of how Thomas Potts Jr. and his son John Potts (1709/10-1768) built their empire, see “Behind the Marker,” explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=1-A-2B3.

[11]“Potts Family,” www.pottstown.org/270/History-of-Borough.

[12]The early history of Mt. Joy Forge is in Tredyffrin-Eastown History Quarterly, 44, nos.1 and 2 (Winter and Spring 2007): 24, .tehistory.org/hqda/html/v44/v44n1+2p022.html.

[13]They had minor criminal and civil jurisdiction in their own right, accepting prisoners of the constables, hearing charges, taking pleas and setting bail. They heard local disputes and required peace bonds or sureties from the parties. They also opened roads and bridges, issued tavern and peddlers’ licenses, and at various times presided over town meetings, levied county taxes, supervised the erection of buildings, appointed overseers of the poor, inspectors of flour and barrel staves, were supervisors of highways, and audited the accounts of the overseers and the county treasurer. Over the years these administrative powers gradually diminished with the creation of other city and county offices and the addition of other officials. Nevertheless, up to the revolutionary period, they were powerful city and county officials. Ward J. Childs, “The Tangible Manifestation of Law, Part III,” in Newsletter of the Philadelphia City Archives, 33 (March 1978). City of Philadelphia Archives, .phila.gov/phila/Docs/otherinfo/newslet/law3.htm.

[14]He was the son of Thomas Potts Jr. by his second wife, Magdalen Robeson. Thus, he was the half-brother of John Potts (1709/10-1768). In his father’s will, he is called “My Son Thomas Potts Jr.” James, Memorial, 82-85. Also, USGENWEB Archives, files.usgwarchives.net/pa/philadelphia/wills/potts-t.txt. Despite that and because the Potts family used the same names, especially Thomas, generation to generation, Daniel A. Graham, specialist on this branch of the Potts family calls him Thomas Potts II. Danial A. Graham, Valley Forge Folklore (Morgantown, PA: Masthof Press for the Montgomery County Historical Society,2019), 47, 48, 49, 93.

[15]William M.’s second son, Thomas, married Hannah Potts in 1763. In 1775, he became the Jailer of Philadelphia.

[16]John W. Jordan, Edgar Moore Green and George T. Extinger, eds., Historic Homes and Institutions and Personal Memoirs of the Lehigh Valley (NY: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1905). 1:45. The information was provided to the editors by an unidentified narrator who described himself as a Stewart descendant of William M.’s daughter, Rachel Dewees Stewart (III-5-24, 1759-1815). Also, La Munyan, The Dewees Family, 89.

[17]In the 1769 tax lists, William M. is shown as a property owner but paid no tax. William Henry Engle, “City and County of Philadelphia,” Proprietary, Supply and Provincial Taxes (Harrisburg, PA: State Printer, 1897), 216. William Henry Engle, Pennsylvania Archives, Third Series,14:216.Rachel shifted her membership from the Friend’s Gwynedd Meeting to the Philadelphia Meeting. “Rachel Dewees,” U.S. Quaker Meeting Records 1681-1935, Ancestry.com, www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2189/images/31906_290395-00282?pId=99373955.

[18]Pennsylvania Gazette, August 4, 1773.

[19]Under established procedures, “two persons (being selected by the People) are presented to the Governor, who approves & commissions them.” “Table Shewing by What Authority Officers Hold Their Places,” in Samuel Hazard, ed., From Original Documents-Commencing 1776.Pennsylvania Archives, Original Series, 4: 601. In other years it appears that the Provincial Council approved and sometimes commissioned or appointed them. John Hill, Martin, Martin’s Bench and Bar of Philadelphia, Together with Other Lists of Persons Appointed to Administer the Law in the City and County of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, PA: Rees Welsh & Co., 1883), 101. La Munyan, The Dewees Family, 87.

[20]The complaint involved the captain of a British ship who had a writ from the Chief Justice directing the sheriff to assist him in seizing some cargo that had been landed without customs. William appeared before the common council and explained how it was a misunderstanding. He was exonerated, but cautioned to always assist His Majesties’ Customs. His appointment was reaffirmed. “At a Council Held at Philadelphia, on Wednesday 5th October, 1774,” and “At a Council Held in Philadelphia, on Thursday the 6th of October, 1774,” Minutes of the Provincial Council 1683-1775,” in Colonial Records of Pennsylvania(Printed by T. Fenn & Co., 1831). Pennsylvania Archives, Original Series, 10: 221.

[21]Pennsylvania Gazette, September 18, 1775 and October 4, 1775.

[22]Digest of County Laws, 1839 (Philadelphia, PA: J. Crissy, 1839).

[23]Richard A. Ryerson, The Revolution is Now Begun. The Radical Committees of Philadelphia, 1765-1776 (Philadelphia, PA: University Pennsylvania Press, 2012). “Philadelphia at this time was in an anomalous condition. It was under a royal parliamentary government that did not dare attempt to discharge any of its functions or enforce any of its laws. It was under a proprietary governor and council who did nothing until the volunteer committees had been consulted. The assembly simply did what was ordered. It was under a municipal government that scarcely looked after the routine of watch, lamp, and street cleaning. The only power of the state resided in a large unwieldy committee which had been nominated by acclimation at a town meeting and only represented the mob. Yet it exercised executive and legislative powers and in the freest manner, and was obeyed cheerfully and implicitly by all.” J. Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, History of Philadelphia: 1609-1884 (Philadelphia, PA: L. H. Everts & Co., 1884), 1:297.

[24]Scharf and Westcott, History of Philadelphia, 1:301-304.

[25]That was accomplished on the initiative of Benjamin Franklin upon his return from England and election to the Pennsylvania Assembly.

[26]The political maneuverings in Philadelphia that moved Pennsylvania from a loyal and pacifist British colony to revolution are summarized in “Appendix XXXIV, section 1, History of the Constitutional Convention of 1776,” Statutes at Large, 452-468. Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, palrb.gov/Preservation/Statutes-at-Large/View-Document/20002099/2023/0/misc/apndx34.pdf.

[27]James Wilson, “Of Government,” in Keith L Hall and Mark David Hall eds, Collected Works of James Wilson. Cited in David B. Kopel, “Posse Comitatus and the Office of Sheriff, Armed Citizens Summoned to the Aid of Law Enforcement,” The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 104 no. 4 (Fall 2014), 793.

[28]Scharf and Westcott,History of Philadelphia, 1: 285-287. Thomas B. Taylor, “The Philadelphia Counterpart of the Boston Tea Party,” Bulletin of Friends Historical Society of Philadelphia, vol. 2 no. 3 (November 1908), 86-110 and vol. 3 no.1 (February 1909), 21-49.

[29]Ryerson, The Revolution is Now Begun, 46, 50, 52.

[31]Scharf and Westcott, History of Philadelphia, 1: 295.

[32]Ryerson, The Revolution is Now Begun, 173. Chris Coelho, Timothy Matlock: Scribe of theDeclaration of Independence (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2013), Chapter Five.

[33]John Adams to James Warren, May 20, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-04-02-0084.

[34]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, July 6,” Records of Pennsylvania Revolutionary Governments, 1775-1790. Pennsylvania Archives, Record Group 27. Scharf and Westcott, History of Philadelphia, 320-321. They mistakenly say “Thomas Dewees was sheriff at the time.” He was the son of William M. and jailer of Philadelphia. The Declaration was already known. See Chris Coelho, “The First Public Reading of the Declaration of Independence,” Journal of the American Revolution, allthingsliberty.com/2021/07/the-first-public-reading-of-the-declaration-of-independence-july-4-1776/. It had also been printed in some Philadelphia newspapers on July 6.

[35]Scharf and Westcott, History of Philadelphia, 1: 320-321.

[36]A short, colorful version of this story is in “We Declare Independence,” American Heritage, 36:1 (December 1984). Many accounts are based on the later life recollections of a young girl not in attendance but living nearby. Deborah Norris Logan Diaries, (Collection #0380), 1826, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

[37]The words are “undivided moiety.” A moiety is defined as one of two equal parts. La Munyan, The Dewees Family, 89.

[38]A map by Garry Wheeler and a description of the complex is in Mike Bertram, “Water and Fire: The Power Behind Valley Forge,” Tredyffrin-Eastown History Quarterly, 41 no.3: 75–84 (Summer 2004), tehistory.org/hqda/html/v41/v41n3p075.html.

[39]Samuel Hazard, ed., Minutes of Council of Safety from June 30th, 1775 to November 12th 1776 (Harrisburg, PA: Fenn, 1851-52), 10: 673.

[40]“William Dewees to the Council of Safety, French Creek Powder Mill Dec. ye 12th 1776.” La Munyan, The Dewees Family, 91-92.

[41]Thomas Verenna, “Explaining Pennsylvania’s Militia,” Journal of the American Revolution, allthingsliberty.com/2014/06/explaining-pennsylvanias-militia/.

[42]“Wm Dewees, Jn’r. to Council of Safety, April 23d, 1777,” La Munyan, The Dewees Family, 90-91.

[43]“Peter DeHaven to Col. John Bull or the Hon’ble Council of Safety, Explosion at the Powder Mill, French Creek, March 1777,” La Munyan, The Dewees Family, 92-93.

[44]“Disposition of Col. William Dewees, 1777,” Pennsylvania ArchivesOriginal Series, 5:261-268. Also, La Munyan, The Dewees Family, 93.

[45]“Appendix B., William Dewees 1785 Petition to Congress,” in Graham, Valley Forge Folklore, 120.

[46]“Board of War to Col. Davis and Others 1777,” Pennsylvania Archives, Original Series, 5:292.

[47]Henry Woodman, The History of Valley Forge: With a biography of the author and the author’s father, who was a soldier with Washington at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777 and 1778(Oaks, PA: John Francis Sr., 1921), 29-40. A family story, perhaps with some element of truth.

[48]Clement Biddle to Washington, September 16, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0236.

[49]Hamilton’s story is in Alexander Hamilton to John Hancock, September 18, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0282. Endnote 1 provides Lee’s story. William F.’s horse was shot out from under him according to Philip Alan Farmer, “Edward’s Relatives and the American Revolutionary War,”philipalanfarmer.com/edwards-relatives-the-american-revolutionary-war/.

[50]Thomas McGuire, The Battle of Paoli (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2006), 179.

[51]“Appendix A. William Dewees’ 1782 Pennsylvania Depreciation Claim,” inGraham, Valley Forge Folklore, 118-119.

[52]The Chester County Register of British Depredations 1777-1782, 171-172, 186. Chester County Archives.

[53]Colonel Frederick Antes House, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Washington%27s_Headquarters_during_the_Revolutionary_War.

[54]Martin, Martin’s Bench and Bar, 101. James Claypoole later requested compensation for his service. He wrote to Governor Reed that he had “continued to do business till September following [when the British occupied Philadelphia].” “James Claypoole Sheriff of Philadelphia to Pres. Reed. 1780,” Pennsylvania Archives, Original Series, 8:321-322.

[55]John Smith Hanna, ed., A History of the Life and Services of Captain Samuel Dewees (Baltimore, MD: Robert Neilson, 1844), 125.

[56]Pelatiah Webster to Washington from, November 19, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0323.

[57]Today, Philadelphia’s Washington Square. “After the British took control of the city in 1778, American prisoners of war suffered in neighboring Walnut Street prison, reportedly going days without meals and capturing rats for food. As many as 12 prisoners died daily, their bodies buried in Washington Square.”John Kopp, “Washington Square: From mass graves to mass media,” www.phillyvoice.com/washington-square-mass-graves-mass-media/.

[58]Graham, Valley Forge Folklore, 100. “Cloyd, Joseph and William Dewees, Jr., Philadelphia County. Pennsylvania. Deposition re Americans . . . held prisoner, Nov. 15, 1777, 3p. M247, 1168, 1152, 115, 1127,” in John P. Butler, comp., Index: The Papers of the Continental Congress (1978), 4.

[59]Washington to William Howe, November 14-15, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0240.

[60]General Orders, October 20, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0569.

[61]See, for example: John Clark to Washington, November 29, 1777,” founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0433; Clark to Washington, December 1, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0443; Clark to Washington, December 3, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0480; Robert Smith to Washington, December 2, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0475; Charles Craig to Washington, December 2, 1777 founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0469; Allen McLane to Washington, November 28, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0427.

[62]William Dewees, Jr., to Washington, December 4, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0496.

[63]J. F. D., Smyth, A Tour in the United States of America (London: Robinson, 1784), 2:422-423.

[64]When Washington had asked his generals, none had specifically suggested Valley Forge. Major General William Alexander had suggested “the Plan of putting the army into Huts in the Township of Tryduffrin in the Great Valley.” Brigadier General John Irvine suggested much the same, advocating hutting the army on the west side of the Schuylkill River twenty to thirty miles from Philadelphia. He emphasized that the Tredyffrin area fit the bill exactly. He also pointed out that “wood is plenty.” Benjamin H. Newcomb, “Washington’s General’s and the Decision to Quarter at Valley Forge,” washingtonpapers.org/resources/articles/washingtons-generals-and-the-decision-to-quarter-at-valley-forge/.

[65]“Appendix B: William Dewees’ 1785 petition to Congress,” in Graham, Valley Forge Folklore.

[66]Graham, Valley Forge Folklore, 92.

[67]Deborah Pywell Potts Hewes was the second wife of Thomas Potts, Jr. William M.’s “beloved frend.” By marriage to Thomas, Jr. she became a step-aunt to Isaac Potts. When William F. married Sarah Potts, she became his step-mother-in-law.

[68]Chester County Register of Deed BookR-2: 249,Chester County, Pennsylvania document center. William F.’s property in Tredyffrinwas adjacent to his father-in-law’s property. Cliff C. Parker, Map: Tredyffrin Township Circa 1777 (Chester County, PA: Chester County Archives, 2021). The Glenhardie Country Club believes that their clubhouse is the site of William F.’s home. While there are numerous errors in their account of how William F. could have come into possession of the home, it may well have been his home. Today, the Country Club property is in the same area as William F.’s property on the 1777 map.

[69]In a letter from Howard Wood, to Jordan, et. al., 1:42. It is part of a story about how Lt. Thomas Stewart (1752-1836) met Rachel Dewees (1758-1815). Rachel Dewees was the eighteen-year-old daughter of William M, who left Philadelphia as the British approached and went to live in the Tredyffrin home of her brother, William F. She is often confused with Rachel Dewees (1765-1838) who was the daughter of William F., age twelve, who was also living there at the time. She later married Lt. Benjamin Bartholomew (1752-1812).

[70]Wayne K. Bodle and Jacqueline Thibaut, “The Bake House (David Pott’s House, Ironmasters house),” in Co-ordinating Research Historians Valley Forge Historical Research Project, (Valley Forge, PA: Valley Forge National Historical Park, 1980), 89-90.

Recent Articles

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

Recent Comments

"Contributor Question: Stolen or..."

Elias Boudinot Manuscript: Good news! The John Carter Brown Library at Brown...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

The new article by Victor DiSanto, "The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched...

"Quotes About or By..."

This well researched article of selected quotes underscores the importance of Indian...