On December 23, 1777, a mere four days after his Continental army entered Valley Forge, George Washington wrote to the Continental Congress expressing the dire needs of his army. He specified that due to catastrophic shortages of shoes and clothes he had “no less than 2898 Men now in Camp unfit for duty.” He went on to explain that this left him with “no more than 8200—in Camp fit for duty.”[1] Although Washington neither combined those numbers nor ever wrote about how many troops in total entered Valley Forge, those two figures from his December 23 letter were routinely reproduced by newspaper and book writers beginning in the middle of the 1800s in describing the Valley Forge experience and the sufferings of the 8,200 fit and 2,898 unfit soldiers who entered it.[2] The first known presentation of the total as the Valley Forge strength upon entry into the camp was within a biographical sketch of George Washington published in 1850, a monograph reproduced to a wider audience in Benson Lossing’s National History of the United States, five years later: “When the encampment was begun at Valley Forge, the whole number of men in the field was 11,098, of whom 2,898 were unfit for duty.”[3]This passage appeared in similar form for the rest of the nineteenth century.[4]

Beginning in the 1890s, publications describing the iconic Valley Forge winter rounded this troop strength down to a simplified “11,000,” an easily remembered number routinely cited for the next 125 years to the present date as Washington’s entry strength on December 19, 1777.[5] From an unknown source, some publications have increased that number to “approximately 12,000 troops.”[6] After consulting “the most meticulous scholars and researchers,” the two authors of a recent publication accepted the range of 11,000-12,000 and also acknowledged estimates up to 2,000 higher than this for the number of soldiers that left Whitemarsh (eight days before they entered Valley Forge).[7] The tradition was that, after entry, disease and hardships from inadequate food, clothes, and supplies reduced Washington’s army significantly below 11,000. According to a National Park Service teaching guide, “It may have been as low as 5,000-6,000 at some point,” before turning steeply on an upswing due to a combination of factors including several thousand new recruits and levees, and the influx of previously hospitalized and furloughed soldiers.[8]

Regardless of these scant and unattributed suggestions of a possibly higher entry force, that original figure of 11,000 as well as the revised 12,000 have never been seriously challenged. The following assessment for the first time analyzes thirty official returns: twenty-seven completed during the six-month encampment of Washington’s Continental army as well as three others surrounding it. The results of this analysis should force a reconsideration not only of the traditionally accepted size of Washington’s force that entered Valley Forge, but also to his army’s actual numerical strength throughout the first half of 1778 in his winter encampment, and the size of the army that departed Valley Forge on June 19, 1778 to embark upon the Monmouth campaign.

How many men entered Valley Forge on December 19, 1777?

Record Group 93 in the National Archives contains four returns of numerical strength of the Continental army compiled in December 1777.[9] The logical starting point for a published and more legible version of half of these is Charles H. Lesser’s The Sinews of Independence, which contains all the monthly strength reports of the Continental Army, re-tabulated in columns quite different but simplified from the original reports.[10] Weekly reports and other field returns for the army were never reproduced in Lesser’s publication.

To come to an understanding of how many men actually arrived at Valley Forge on December 19, 1777, we need to look back to December 3, 1777, when the previous monthly strength report was competed for the army. For this analysis all fifteen present-for-duty columns for officers and men were combined with “sick present” men and “on command” men to assess the bulk of the soldiers that comprised the main army. This gives 22,824 men in seventeen infantry brigades, five independent regiments, and the Pennsylvania and Maryland militia.[11] The December 3 strength report does not include Daniel Morgan’s independent corps, the four regiments of light dragoons, or any of the army’s artillery.

The light dragoons are included on the December 31 return with 497 men at Valley Forge which suffices as their strength four weeks earlier.[12] After casualties at Saratoga and the long march south to rejoin Washington’s army, Daniel Morgan joined the main army with 300 men, a conservative estimate. A December 22 artillery return located in the Timothy Pickering papers lists 754 men present.[13] Therefore, 760 is a reasonable representation of their strength at the beginning of the month. When these units missing from the December 3 strength report are added to the 22,824 men delineated on the report, the army had approximately 24,381 in its camps at Whitemarsh, Pennsylvania, on December 3, 1777. If we accept the “traditional” number of 11,000 troops marching into Valley Forge, what happened to 13,000 men of Washington’s army over those sixteen days? Maybe nothing.

Certainly, casualties were inflicted on the army at Whitemarsh, Matson’s Ford, and other minor skirmishes over that time span. But those casualties only totaled approximately 300 men in these relatively minor actions.[14] That brings army strength down to 24,081 prior to December 19. Do we really believe over 13,000 men simply deserted or vanished in sixteen days?

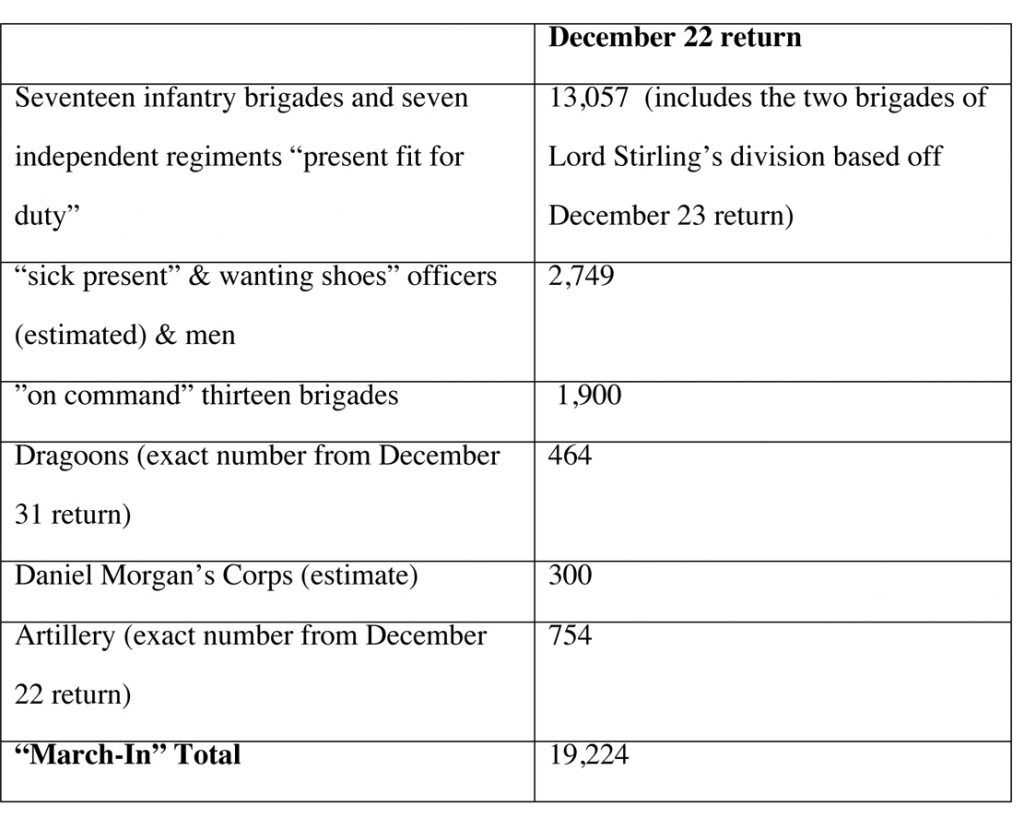

Only a few 1777 weekly reports compiled for the Continental army remain in existence today; fortunately, the December 22 report—the first and closest one for determining the number of troops that entered Valley Forge—is among those few.[15] Much like the routine monthly army returns, the template of columns and rows on the December 22 weekly report consists of twenty-one columns where numerical strength was tabulated: fourteen columns within an “Officers Present” section, a Rank & File section subdivided into six columns of present and absent categories, culminating into an aggregated “Total” for only these foot soldiers. The present-for-duty numbers do not include other men present in camp: those listed as “sick present” and “unfit for duty wanting shoes.” Both must be included in the army’s total presence during an encampment. There is also no accounting of sick officers that were present with the army when it marched into Valley Forge. Lastly the December 22 report enumerated infantry only; there is no accounting of artillery or cavalry personnel—numbers that would significantly add to the army’s strength.

Of special importance is the “On Command” column of all weekly and monthly reports which tallies soldiers detached from their respective regiments and brigades for temporary service where additional manpower was required. Examples of this include assistance to the commissary and quartermaster departments, additional servants for officers, or household duties such as butchers or bakers. The calculation of fifty-eight percent of the “on command” force as readily available in an emergency was formulated in May, highlighting that most of these special-duty assignments were conducted within camp boundaries.[16] A much higher percentage of soldiers in the “On Command” column in the December 22 report at least marched into camp with the army before being dispersed to their respective duties. Given that the two brigades under Lord Stirling were not included in this column, it can be assumed that from the remaining thirteen brigades (approximately eighty-five percent) nearly all the reported “On Command” soldiers entered Valley Forge on December 19.

The weekly strength report for December 22, 1777 enumerates 11,026 officers and men present for duty at Valley Forge just three days after their arrival.[17] While this number approaches the “traditional” 11,000 men that entered Valley Forge, a close analysis of that number quickly sends up red flags for the careful researcher. This report was never cited in any nineteenth, twentieth or twenty-first century literature; the rounded “11,000” officers and men initially tallied in this report is purely coincidental to the 11,098 privates determined from Washington’s letter to Congress.

First, the total number of soldiers in the two Maryland brigades that left for Wilmington, Delaware, prior to the “march-in” at Valley Forge—1,768 men—did not march into Valley Forge. Next, the three independent regiments that were sent to Lancaster, Pennsylvania (which departed after entry into Valley Forge and before December 22) can be confidently added back to the march-in force by an existing tally of their strength on December 31. Also, the two brigades of Lord Stirling’s division are missing on the December 22 return, but their numbers present can be generated from a separate report of their strength compiled the following day.[18] In addition to thousands of present but unfit soldiers, also missing from the December 22 report are Morgan’s independent corps, the dragoons, and the artillerymen. Factoring in these “missing” units from the nearest existing report of their respective strengths brings the army strength up to 19,224, only 4,857 less than the army’s strength at Whitemarsh after casualties. Pennsylvania and Maryland militiamen were included on the December 3 return but do not appear on the December 22 return because they did not arrive at Valley Forge with the Continental troops.

The army George Washington marched into Valley Forge on December 19, 1777 was not the 11,000-man force “tradition” and poor source analysis has led us to believe, nor was it the 12,000 or even up to 14,000 that more recent sources equivocally suggest. While the army did suffer about 1,800 deaths, desertions and/or absent sick troops during the month of December, roughly 19,000 soldiers entered Valley Forge on December 19 to begin the winter encampment.

George Washington’s initial Valley Forge troop estimate of 11,098, broken down to fit and unfit soldiers on December 23, originated from a field report he ordered to be completed earlier that day, surprisingly a totally different report from the one completed the previous day.[19] The December 23 return enumerates 12,484 infantry soldiers present at Valley Forge by including noncommissioned officers not mentioned in Washington’s letter to the Continental Congress. This stripped-down report omitted several thousand soldiers present in camp that day (no dragoons, artillery, commissioned officers, present sick officers and men, and shoeless officers were included).

A tremendous discrepancy exists between an equal comparison of brigades in the December 22 and 23 returns that cannot be resolved. Adding in present foot soldiers in these brigades that were tallied on December 22 as “sick present” still fails to explain the three-fold increase in naked or shoeless soldiers counted one day apart, as well as the discrepancy of 557 fewer noncommissioned officers that were enumerated in consecutive days from the exact same brigades. Given that the trend lines in the subsequent report to this (December 31) dovetails well with each category of the December 22 report – including fewer than 1,000 unfit soldiers due to poor clothing – the December 23 report cannot be considered an accurate representation of what existed at Valley Forge in the last days of 1777.

How Many Troops Were Present in Valley Forge Throughout the 1778 Winter/Spring Encampment?

This is the appropriate question to ask as the troops residing at Valley Forge were an encampment force, not a battle-ready one. Washington’s December 23 letter had emphasized the latter as he was seeking to attack the British army in Philadelphia but was forced to abandon the plan due to the high percentage of soldiers who were in camp but deemed unfit to march for a planned assault. From this point onward, Washington’s prime concern was to feed and supply his professional army and prepare them for the following season of campaigning.

Fortunately, the question can be answered with a high degree of confidence, particularly in contrast to the number of troops present during the active months of the previous autumn’s Philadelphia Campaign. Although merely a handful of 1777 army troop-strength reports survive, routine monthly and nearly-weekly returns exist throughout the winter and spring of 1778. In total, twenty-seven reports were produced during the six-month encampment, six end-of-month returns, the aforementioned December 23 special field return, as well as twenty weekly reports using the same template as the monthly returns (it appears the February 2 weekly return also was used as the end-of-January monthly report).

These weekly and monthly troop-strength returns routinely consisted of twenty-nine columns: the aforementioned columns for Officers and Rank & File, and also a section for “Alterations” of officers and men, subdivided into eight more columns for permanent losses (“Deaths,” “Deserted,” and “Discharged”) and columns for newly enlisted, recruited or leveed men all sub-grouped as “Joined.” Adjutants for every Continental brigade in each winter encampment site completed a return at the end of every month as well as the time the weekly ones were due. These results were compiled in an encompassing army troop-strength report by the adjutant general for the Continental army.

To answer the question that opened this section, these returns were analyzed and pinpointed to what was routinely tallied, and what could be derived from those routine tallies. This limited the analysis to Continental army field and staff, commissioned and noncommissioned officers and privates (the latter referred to as “rank & file” in all reports), attached to infantry and artillery regiments only, present at Valley Forge only. This decision necessarily filtered out militia, even though they periodically appeared on Valley Forge returns. Continental cavalry relocated from Valley Forge in 1777 to Trenton in the winter of 1778 were also omitted from this count. Additionally, no brigade, division and army staff are included even though they were Continental officers at Valley Forge. Given that four division commanders and fifteen brigade commanders were present for nearly the entire duration, this omission removed more than one hundred professional soldiers—including every general and his staff. Most notably, George Washington and his military family of secretaries and aides were never enumerated in Valley Forge official returns.

Several hundred noncombatants who typically were present at Valley Forge throughout the six months were also left off these tabulations as they were also eliminated from the original returns. This included teamsters, household staff, artificers, enslaved persons, family members, and citizens of the region. Combining these noncombatants with the aforementioned and excluded Continentals at Valley Forge omitted several hundred temporary as well as routine residents of the encampment during those six months.

The most underappreciated aspect of the traditional history associated with Valley Forge is the number of Continental soldiers who are usually disregarded as part of Washington’s winter encampment because they wintered away from Valley Forge. Gen. William Smallwood’s two Maryland brigades encamped in Wilmington, nearly thirty miles south of Valley Forge. They suffered similar hardships as their Valley Forge brethren, as did isolated Continental regiments that encamped well outside the boundaries of Valley Forge, including an artillery unit also stationed in Wilmington. With the exception of December’s monthly return, Continental cavalry was stationed in Trenton for most of the winter encampment, an arm of Washington’s army usually tallying over 400 officers and men. During the period in which these troop-strength returns were compiled, between 1,500 and 2,500 Continental officers and men who served under George Washington were present within a two days’ march from Valley Forge in other winter encampment sites.

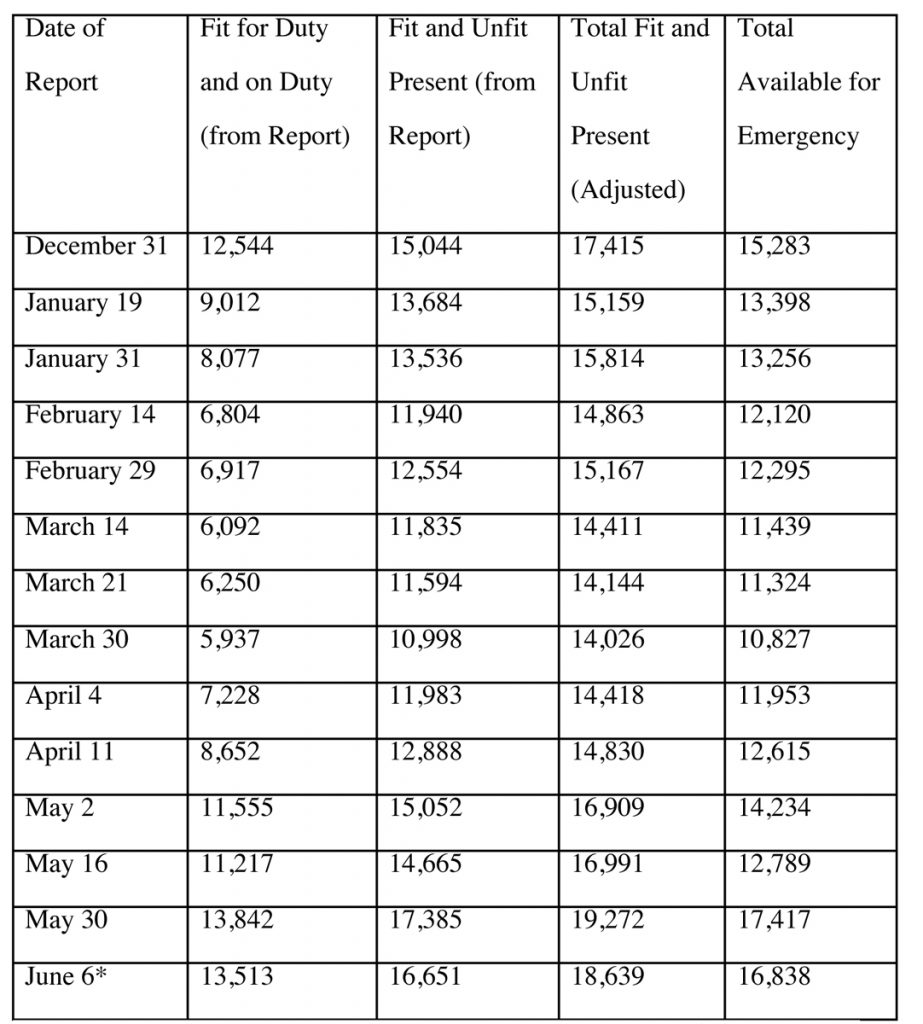

Limited to the Continental army present at Valley Forge, four distinctive avenues exist to depict numerical strength from these returns—two of them direct and two others derived. Most directly, the number of troops tallied as present and fit for duty and on duty with their regiments is directly available from the reports without any adjustments. George Washington routinely cited this value, but did so only for infantry rank and file, omitting all artillery as well as infantry commissioned, non-commissioned and staff personnel. For this investigation, all Continental officers and privates, infantry and artillery, present and fit for duty are tabulated.

On the cover of the May 2, 1778 troop strength return, elements of a numerical formula appear which calculates a rank & file force “that might act on an emergency.”[20] The clear assumption for this is to derive a strength report if the encampment came under attack. Based on the numbers scrawled, for Valley Forge and similarly for Wilmington, this is the formula:

Emergency Force = Present fit for Duty + 2/3 of sick present + 4/7 of “On Command”

This formula determined how many troops were readily available, presumably healthy enough to defend a position rather than march to and charge one. The calculation of fifty-eight percent of the “on command” force as readily available in an emergency best translates to four out of every seven of those soldiers performing those extra-service duties within the Valley Forge encampment. Although the likelihood that even a higher percentage of “on command” soldiers were in Valley Forge in the months preceding May, the four-sevenths calculation can be safely applied to all reports preceding May to minimally but rightfully add in soldiers routinely overlooked as present in camp within these returns.

Two considerations are required for soldiers who were in Valley Forge but not tallied in the weekly and monthly reports. One of those considerations includes officers sick and present in camp. Although the winter of 1778 tabulated only rank & file soldiers in this category, a study of the first five months of 1779 indicates these numbers existed in a separate officer’s report which was likely added to the returns based on significant numbers never tallied in 1778. Similarly, the total force present at Valley Forge must be at least minimally adjusted to account for officers deemed unfit due to “Wanting Shoes and Cloathes.” For both considerations, it is believed that within the officer ranks only non-commissioned personnel—sergeants, fifers and drummers—became sicken and wore out shoes and clothes at close to the rate of privates and at a much higher rate than commissioned officers and staff personnel like chaplains and paymasters. For each time point of the encampment, the percentage of noncommissioned staff present in camp but unfit due to illness or poor clothing compared to their total is likely similar to the percentage of privates present and unfit for the same reason (the calculation applied equates to three to four percentage points lower than the privates). Adjusting only for noncommissioned personnel considered present but unfit because they were ill or ill-clad makes the obviously erroneous assumption that no unfit commissioned officers and staff officers remained in Valley Forge; this assumption is nonetheless applied to insure no false inflation of the numbers in the encampment during any week or month.

Troop-strength reports exist for nearly every week of the encampment. Of these, nearly half were chosen for this analysis, representing at least two time points per complete month of the encampment. Table Two includes both raw and adjusted data to depict four different ways to represent the numerical strength of the officers and men of the Continental army at Valley Forge at fourteen time points between December 31 (twelve days after entry into camp) and June 6 (thirteen days before departure). The first column depicts all who were present and deemed fit for duty from each report. The second column adds in only privates present in camp but deemed unfit due to illness or poor shoes or clothes, as they were reported in each of the fourteen returns. The third column is the total of the first two columns plus the previously explained adjustment for “on command” rank & file still in Valley Forge, as well as the minimized correction for officers present but unfit for poor clothing and illness. This third column brings us closest to the actual number of men residing in the camp, exclusive of brigade, division and army officers as well as their staffs, servants and families, and other citizens and workers not considered Continental army personnel. The final column tabulates the emergent force of officers and men from the third column thatcould be expected to defend the camp if it came under a surprise attack. For December 31 only, an additional 600 men are added to both the third and final columns to account for Continental artillery officers and men who were indeed at Valley Forge to begin 1778, but not tabulated in that specific return.

* Fourteen brigades tallied; all other time points tally fifteen infantry brigades.

The revised data reveals that even during the leanest period at Valley Forge (the final week of March 1778), the Continental army never dipped below 14,000 officers and men present in camp. The nadir for present and fit for duty numerical strength (first column) appears to be the entire month of March which may be what the published National Park Service curriculum guide alludes to; however, tracing all three weeks of that month from left to right on the table indicates how misleading this particular column truly is, even for determining a force that could defend the camp during an attack. Better appreciated is the third column which most closely represents the true total numerical presence of the Continental army that winter and spring, a population in Valley Forge that most of the time equaled or exceeded the population of Boston, then the third most populous city in the United States of America.

How Many Men Departed Valley Forge on June 19, 1778?

Having analyzed how many men arrived at Valley Forge with George Washington and how those numbers fluctuated during the encampment, how many freshly trained and reorganized troops left with him for the Monmouth Campaign?

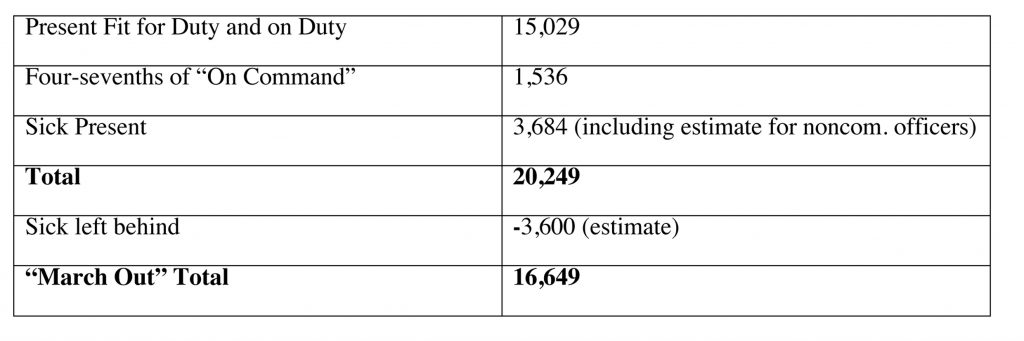

A June 13, 1778 weekly return exists in the National Archives, prepared just six days prior to the army’s departure for the Monmouth Campaign.[21] This strength report for the army lists 15,029 “present fit for duty & on duty” (due to blurry conditions on the original scan, present officers were calculated from a June 22 field report.[22] After adjustments, approximately 16,649 Continental troops marched out of Valley Forge with George Washington (3,600 sick men were left behind). This estimate conflicts with what Washington wrote on June 17 after a council of war. He stated the army had 12,500 men fit in case of emergency, but Washington throughout the war calculated his estimates based on musket-carrying men.[23] He rarely included officers, artillery, or cavalry in his estimates. The June 13 weekly report lists 12,777 rank and file infantry present and fit for duty which did correspond closely to Washington’s June 17 estimate (not including the corrections for adding in sick and “on command” soldiers available for an emergency). En route to the battle of Monmouth nine days later, the New Jersey brigade, light dragoons, and New Jersey militia joined the army adding approximately 2,999 men to the army’s strength. The army’s total present strength approaching Monmouth, therefore, likely exceeded 19,000.

Conclusion

This is the first comprehensive analysis of present-in-camp troop strength of George Washington’s army at Valley Forge between December 19, 1777 and June 19, 1778—based on a study of twenty-seven completed returns during the encampment as well as a comparison to the most immediate returns before and subsequent to these. Our analysis indicates 19,000 Continental soldiers initially marched and rode into Valley Forge, a total force that diminished to nearly 14,000 late in March at Valley Forge at its absolute nadir, before swelling to a numerical strength in May which re-established the Valley Forge encampment as the third highest population center in the United States.

The implications of this very necessary revision are far-reaching ones, particularly in understanding George Washington’s supply woes in supporting an army at least 50 percent more numerous in camp than ever has been appreciated before.

[1]Washington to Henry Laurens, December 23, 1777, in Philander D. Chase, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002),12: 683-87 (numbers presented on page 685).

[2]“Chronology,” WilliamsburghDaily Gazette (Brooklyn, New York), December 19, 1850.

[3]“Biographical Sketch of George Washington,” in Edwin Williams, The Presidents of the United States, Their Memoirs and Administrations(New York: Edward Walker, 1850), 43; Benson J. Lossing, The National History of the United States, Vol. 2 (New York: Edward Walker, 1855), 45.

[4]“Washington at Valley Forge,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, February 20, 1886, “The Park at Valley Forge,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 22, 1893.

[5]John F. Jameson, Dictionary of United States History. 1492-1895(Boston: Puritan Publishing Co., 1894), 674.

[6]Stephen R. Taaffe, The Philadelphia Campaign 1777-1778(Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003), 150.

[7]Bob Drury and Tom Clavin, Valley Forge(New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 107.

[8]National Park Service, Valley Forge National Historic Park Curriculum Guide(Washington, D.C.: Department of Interior, n.d.), 21, www.nps.gov/vafo/learn/education/upload/curriculumguide.pdf.

[9]These records are available at www.fold3.com.

[10]Charles H. Lesser, ed., The Sinews of Independence: Monthly strength Reports of the Continental Army(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976). See pages 53-78 for returns between December 1777 and June 1778.

[11]December 3, 1777 report compiles troops considered as November’s strength and is summarized in Lesser, Sinews, 53

[12]Copy of December 31, 1777 return, www.fold3.com/image/9151410; also see Lesser, Sinews, 55.

[13]Timothy Pickering Papers, Microfilm Roll 56, page 156, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[14]Howard H. Peckham, ed., The Toll of Independence: Engagements & Battle Casualties of the American Revolution (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1974), 45.

[15]December 22, 1777 Weekly Report, www.fold3.com/image/9151405.

[16]May 2, 1778 Weekly Report (cover), www.fold3.com/image/9151560.

[17]December 22, 1777 Weekly Report, www.fold3.com/image/9151405.

[18]Field Return, December 23, 1777, www.fold3.com/image/9151423

[20]May 2, 1778 Weekly Report (cover), www.fold3.com/image/9151560.

21 June 6, 1778 weekly return, http://fold3.com/image/9151600.

22June 22, 1778 Field Return, http://fold3.com/image/9151790.

23“Council of War,” June 17, 1778, Papers of George Washington, 15: 415.

14 Comments

The title gives one to believe, Washington attacked the British at Trenton. Didn’t he actually attack the Prussian Mercenaries from Valley Forge? No mention of it. Now granted the Prussians were paid by England and could in a round about way be “British”. Also any one who was in the Military and had to deal with Congress knows, you “adjust” the numbers and pray they give you the supplies you need. Good read, and thoroughly enjoyed it.

Folks sometimes confuse the Schuylkill River at Valley Forge with the Delaware River at Trenton, and ask me if that’s where Washington crossed to ruin the Hessian’s (not Prussian) Christmas celebration. Well, the Battle of Trenton was a full year earlier than the encampment at Valley Forge… Dec. 25, 1776 versus the march into VF on Dec. 19, 1777.

Wonderful stuff!

Excellent article. Thank you for shedding new light on this.

Very interesting article. Were any Cape May militia with the army at Valley Forge? My ancestor was a member of Captain James Willets company from 1777 to 1778.

John,

No, the NJ militia was not at Valley Forge. They returned to New Jersey not long after the Battle of Germantown.

Like the article. Consider using reports of rations issued to further enhance your research.

What an important contribution to the Valley Forge story! Huzza!

I am descended from William Dewees, co-owner of Valley Forge. There are many memoirs of the Dewees family as well as their neighbors, the Boyers, interaction with Washington and his officers during the encampment. William Dewees spent years of futile pleading for reparations from the new government for all the damages instilled on his property, first by the British followed by Washington’s army.

Great scholarship! With findings like this, Mike and Gary are

proving themselves to be at the forefront of developing new research on the Philadelphia campaign. Bravo guys!

Great scholarship! With findings like this, Mike and Gary are

proving themselves to be at the forefront of developing new research on the Philadelphia campaign. Bravo guys!

This is excellent, meticulous work! A few thoughts for color and consideration, one or two of which could marginally impact your calculations. 1) Soldiers detached to Morgan are listed on at least some regimental musters as “on command.” (e.g., 8th Va.) Though not more than 300 men, you might be double-counting them. 2) I confess it has been an assumption, but I have always thought “on command” meant detached or out of camp (foraging, detached to Morgan or Maxwell, sent to Mud Island, etc). 3) The 8th Pa. and 13th Va. were sent to Fort Pitt about this time. 4) I gather there are no numbers for “sick/absent” (hospitalized or left behind) soldiers on the strength reports. Some number were at remote hospital sites or area churches convalescing. Not sure how these figure in the tallies but they are visible on at least some regimental musters. 5) All original spring 1776 enlisted men in the 3rd through 9th Va. regiments were on 2-year enlistments that expired while they were at Valley Forge. Most did not reenlist.

Again—really impressive work here.

Thanks to all who shared their interest in our work and for the positive response to our findings. We are confident that this is a minimalist approach to the actual numbers in camp. That said, observations of detached units and expired service can certainly influence the numbers (and provide evidence to the fluctuations of daily presence at Valley Forge); however, the weekly reports were all tabulated at the brigade level which reveals that if men from regiments or entire regiments were not physically present in camp at the time of the roll, they were not counted–this would be particularly true of expired services of entire regiments. Table 2 was created to show the chronological ebb and flow of 14 (out of 27) time points and would pick up detachments that left and returned within a two-week span. There is indeed a separate column for “sick absent” for men removed from camp and sent to Yellow Springs and other hospital sites. We never counted these troops as present — only the separate column “sick present” soldiers who stayed at Valley Forge.

The “On Command” column tallies all the men of the brigades that are not physically present with their respective regiments at the time of the roll; this is why they are traditionally considered not present for duty. The Adjutant General’s calculation on the cover page of the May monthly report reveals nearly 60% of these men were considered available in case of an emergency. That convinces us that they were conducting special duties within the confines of camp or so close to camp boundaries that they could be counted upon to be readily able to help repel a surprise attack by the British at Valley Forge. We assume that “on command” detachments even five miles away from Valley Forge would not be part of that ~60%. As for Morgan’s men who were in this column, we only counted them as an additional component of the entry force into Valley Forge on December 19, 1777 . They were never tallied as additional troops after this date.

Here’s a quote from the diary of my ancestor Joseph Clark, deputy commissary of musters, who was with the army when it entered Valley Forge:

“Friday, Dec. 19th – The camp moved to near the Valley Forge, where we immediately struck up temporary huts covered with leaves. In a few days we began the building of our log huts. About the 21st of the month a large foraging party of the enemy came out towards Darby. Several scouts from the army, with Col. Morgan’s riflemen, went down to oppose them, and had several skirmishes, in which, by what I can learn, each fared nearly alike. The enemy, however, after plundering the inhabitants severely, went back to the city, and our scouts returned to camp. General Sullivan’s division, under the command of Brig. Gen. Smallwood, removed from the camp to Wilmington. Gen’l Sullivan undertook the direction of building a bridge over the Schuylkill. The building of our log huts at this time was going on very fast.”

So Sullivan’s division entered the camp on the 19th but then left on the 21st, it appears.