Most modern historical treatments of the American invasion of Canada disparage Brig. Gen. David Wooster for his leadership in Canada. A detailed examination of his command from January to May 1776, however, lends credence to an early biographer’s conclusion that “Gen. Wooster was censured by those who did not know the obstacles he had to encounter.” One episode particularly illuminates Wooster’s skilled leadership during the campaign, when he kept his army intact outside Quebec City for weeks after one half of his men’s enlistments ended.[1]

Wooster’s command began on January 5, 1776, when news of an unexpected misfortune reached his headquarters in occupied Montreal. His superior, Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery, had died in a failed New Year’s Eve assault on Quebec City. Wooster was suddenly responsible for all Continental operations in Canada. The sixty-five-year-old Connecticut general had vast leadership experience as an acclaimed captain in the 1745 siege of Louisbourg, as well as from provincial regimental and brigade commands in the French and Indian War. Unfortunately for him, he was already burdened by a troublesome reputation in the Revolutionary War that developed before he ever got to Canada.

Part of Wooster’s notoriety was rooted in his own imprudent statements—especially regarding his disappointment that he, Connecticut’s senior major general, had only been appointed a Continental brigadier—and his provincial predilections in a time of rising Continental spirit; but circumstances served to exacerbate his fractious reputation when he struggled with an ambiguous chain of command over the summer of 1775 while leading an independent force protecting New York’s coast. Many peoples’ first impressions that summer would taint subsequent assessments of Wooster’s abilities and performance. Northern Army commander Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler was among those quickest to find fault with Wooster. That fall, Schuyler had even been disinclined to send the controversy-burdened Connecticut brigadier into Canada at all, writing, “as his Regiment refused to go without him, I was obliged to suffer him to go.”[2]

When Wooster assumed command in January 1776, he was 170 miles from his frontline forces—the thousand survivors of Montgomery’s defeat who still blockaded Quebec City under Benedict Arnold. Assessing the dangerously fluid situation in Canada, Wooster judged it best to remain in Montreal where he could secure the weak army’s retreat path in case circumstances worsened, and coordinate reinforcements as soon as possible. To stem further manpower losses from his undermanned army, the general followed Arnold’s advice to prohibit any soldiers from leaving Canada—keeping two hundred men at Quebec whose enlistments had expired on January 1.[3]

On his own authority, Wooster also wrote to Col. Seth Warner, asking him to re-establish the Green Mountain Boys and rush north to provide stopgap assistance until new Continental regiments could arrive. The first of Warner’s men began reaching Canada in the last week of January and marched on to Quebec City, followed by western Massachusetts companies led by Maj. Jeremiah Cady and other militia volunteers. Even with these short-termers arrivals, by mid-February Arnold still had just 1,345 Continental soldiers to maintain long blockade lines, and 385 of them were non-effective due to smallpox and other sickness.[4]

General Wooster regularly corresponded with his superiors, requesting substantial augmentation—echoing Schuyler’s call for ten thousand men to hold Canada through the spring. The common and correct assumption was that incoming regiments would be racing a massive British relief force coming to Quebec by sea, that would undoubtedly arrive when the ice cleared in early May. Wooster also stressed that everyone coming from the colonies should get to Canada before mid-March, when spring thaws would halt northward transportation for several critical weeks mid-race. The Continental Congress initially responded to Wooster and Schuyler’s reinforcement requests by directing five regiments to Canada—already-formed Pennsylvania and New Jersey units, and newly established ones from Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Connecticut.[5]

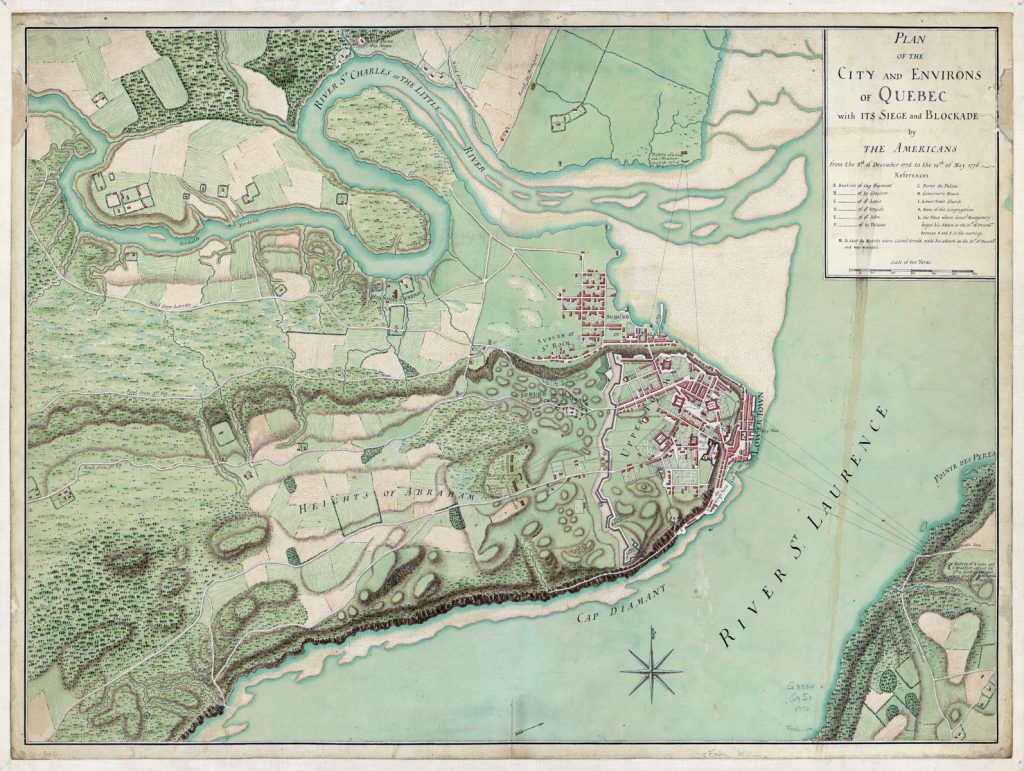

Once the first wave of these men entered Canada in mid-March, Wooster deemed the situation in Montreal stable enough to join his troops at Quebec. Arriving on April 1, he reconnoitered enemy defenses and evaluated his forces. His own army had grown to more than 2,500 men, ill-clothed, poorly supplied, and stretched too thin—almost one-third perpetually sick. While Wooster publicly boasted of storming Quebec City to keep up spirits, he was a realist with siege experience. Facing about 1,500 well-led men inside a fortress city, and with wildly fluctuating April weather thwarting the simplest tactical maneuvers, an assault was almost certainly a suicidal proposition.[6]

Wooster needed at least two thousand more men before realistically considering an attack. So, in early April he had two principal courses of action. He could preemptively retreat; but this seemed impetuous and hasty, knowing thousands of troops were on the way and that Maj. Gen. John Thomas was due to come take command in Canada soon. Wooster selected the other, more logical course: sustaining the blockade until reinforcements arrived—postponing attack or retreat decisions while the situation clarified over the next few weeks. Inbound regiments could rapidly tilt assault odds in his army’s favor if they arrived before the British; but Wooster had no way to know when Thomas or the additional American troops would actually get to Quebec.

Despite Wooster’s warnings about the seasonal halt in northward travel, only advanced echelons of the five promised regiments reached Quebec by the beginning of April. The others were predictably idled, waiting for water routes to open. Wooster’s army was strong enough for the short term, but a potentially ruinous challenge loomed on April 15—when the enlistments of about 1,800 soldiers at Quebec would expire. The general faced the prospect of losing more than half his force, opening gaps in the blockade and perhaps even inviting enemy sorties. Wooster embraced the leadership challenge of keeping these men in camp.[7]

Even just one year into the war, the Continental Army already had two precedents for Wooster’s expiring-enlistment plight. In late 1775, Montgomery’s soldiers in Canada were due to be discharged just weeks after taking Fort St. Johns and Montreal, but the general needed men to join Arnold near Quebec and occupy Canada over the winter. On November 15, he implored soldiers to reenlist for just another five months, convincing about one quarter to stay: 260 New England men and 690 New Yorkers—many of the same men ready to leave Quebec on April 15, 1776.[8]

Washington had also faced comparable challenges at Cambridge, Massachusetts. When the entire Continental Army was due to be formed anew on January 1, 1776, early re-enlistment efforts left it about ten thousand men short of target strength at year’s end. Washington, unlike Montgomery and Wooster, could turn to nearby governments for help; he requested and received five thousand militia men to help fill the lines while recruiting efforts continued, but it would be March before the commander regained confidence in the army’s strength.[9]

Both Montgomery and Washington had seen the truth in Gov. Jonathan Trumbull’s characterization of a typical liberty-loving American soldier: “His engagement in the service he thinks purely voluntary; therefore, in his estimation, when the time of inlistment is out, he thinks himself not holden without further engagement.” And Wooster’s soldiers outside Quebec faced further disincentives to continue even a day longer. Fall campaign veterans had already re-enlisted once or had been involuntarily kept into the new year. They had endured a harsh Canadian winter and rampant disease, gone months without pay, and even when released, faced a grueling four-hundred-mile trip home. Even the western New Englanders who arrived in 1776 had only agreed to come north in the dead of winter for short-term service. There was little reason to doubt Col. Moses Hazen’s prediction that “neither art, craft, nor money, will prevail on any of them to reinlist to serve in Canada.” The deck was stacked against Wooster.[10]

If Wooster had one factor in his favor, it was his long-established reputation as a magnanimous officer, a “soldiers’ friend and protector”—particularly with Connecticut men. But half of the troops due to be released were New Yorkers, who grumbled in camp that their Yankee commanders—Arnold, then Wooster—affected a “disgusting Superiority” and favored New Englanders. Arnold’s April 10 departure for Montreal presumably helped Wooster in this regard, though: many winter veterans were unhappy with Arnold’s haughty leadership, and New Yorkers were further displeased by indiscreet, disparaging comments he had allegedly made about their courage in the New Year’s Eve defeat.[11]

Wooster’s foremost method for keeping men in camp was through one-year reenlistments. Congress had authorized two regiments to be formed from soldiers already serving in Canada—one each of New Yorkers and New Englanders. By April 8, few soldiers had signed on for another year though, so Wooster announced a re-enlistment bounty, advance pay, and permitted individuals to freely choose which unit to join, including the Green Mountain Boys, Elisha Porter’s Massachusetts Regiment, and the artillery company. Also, to get re-enlisting troops closer to home, he asked Congress to rotate the two new regiments back to the colonies as soon as practical. Still, by mid-April, less than five hundred had willingly re-engaged, about one quarter of those eligible—roughly comparable to Montgomery’s November results.[12]

With the re-enlistment option played out, Wooster tried another tack on April 13. In general orders, he appealed to the patriotism of the thousand men whose commitments expired in two days, entreating them to continue “until the Reduction of Quebeck or the fate of it is determined.” Wooster offered one month’s advanced pay and provisions for their postponed homeward treks—otherwise they would have to acquire food over several days’ march back through Canada. The next day, Wooster negotiated a behind-the-scenes arrangement for most New Yorkers to remain until the end of the month. He also worked with key New England leaders; as one soldier recollected, “the officers of our regiment were persuaded to remain & detain the troops, until reinforcements might arrive.” The Green Mountain Boys, Cady’s detachment, and Maj. John Brown’s detachment would stay under Wooster’s terms. The general had quietly extended all but one or two hundred men at this “Critical Conjuncture of Affairs.”[13]

Once the April 15 deadline arrived, Wooster resorted to another alternative—the tools of military discipline—to detain the uncommitted remnant. By order, soldiers could only leave in small groups under an officer, who had to submit men’s names for “proper paper to be made out” before departure. The general knew that in past months, small reinforcement detachments had been notoriously plundering and insulting locals on the way to Quebec, so these new policies established a foundation for order among homeward-bound troops. Wooster’s staff exploited these requirements to impose additional delays: when officers appeared at headquarters for passes to leave, they were told to come back at a later date; units formed to be mustered out, but the muster master never showed.[14]

Some soldiers refused to passively suffer these impositions. On April 17, about forty New Yorkers rose up in “very mutinous behavior.” Marching to headquarters, they laid down their weapons, complained of being “deceived & ill-treated,” demanded “Liberty to go home,” and even threatened to plunder Canadians for food if not given provisions for their departure. Col. James Clinton, the senior New York officer, assembled troops who promptly broke up the insurrection and arrested protest leaders. Seven were tried by court martial; five judged guilty of insubordination and sentenced to be whipped, two also to spend a month in irons. Wooster did not show mercy in this critical period—all punishments were administered the morning after he approved the verdicts.[15]

The day after the uprising, April 18, Wooster announced that “Principles of Humanity” required him to “Interpose his authority” once again. To keep discipline and prevent soldiers from plundering Canadians, he mandated that “no man or Body of Men, Under penalty of suffering the Severity of Military Punishment,” could “leave the Camp till the boats come down the river.” Wooster had readied several ships and large boats to deliver reinforcements and supplies to Quebec once ice cleared from the St. Lawrence. Properly released soldiers would be permitted to embark on these vessels for upriver return trips to Montreal. Wooster’s order served three purposes: keeping the men longer; reducing the risk of pillaging during travel; and rewarding cooperative soldiers by shortening their return march distance by almost one third.[16]

That same day, Wooster offered another enticement. Forming the soldiers on parade, he revealed a heretofore secret plan. He had fitted out a fireship to burn enemy shipping in Quebec’s Lower Town, ready to be employed once conditions were right. If the men remained patient, this scheme at least offered the “promise of a feu de joie”—a fireworks spectacle; and if it went well, it might facilitate Quebec City’s capture, with sanctioned shares of plunder for soldiers still on extended service. Most troops were presumably unenthusiastic about staying several days longer, but there was no further unrest.[17]

After ten days further delay, Wooster’s river transports finally arrived; his delaying tactic for the New Yorkers had expired. On April 30, hundreds of them sailed for home. That day, and on each subsequent day, Wooster also issued passes and provisions for a small detachment of men to leave by land, regulating the departure flow and minimizing the threat to Canadians on return marches. These were the few hundred men who had not accepted his April 14 terms to continue until Quebec’s fate was determined.[18]

On May 2, Major General Thomas finally arrived to assume command. Thanks to Wooster’s efforts, Thomas found two thousand men in camp. In the critical span from April 15 to May 2, approximately one thousand new men had reached Quebec, offsetting those released at April’s end. Wooster could not have made the army any stronger on his own, but he had kept it from being reduced to dangerous levels. Contemporaries at Quebec specifically credited him for it. Patriot Hector McNeill testified: “He thinks Wooster’s going [to Quebec] was lucky, as he kept the men there, which he thinks Arnold could not have done.” Ultimately though, Wooster’s generalship only bought the army time to face even bigger problems.[19]

With his late arrival, Thomas had mere days to make the attack-or-retreat decision that Wooster had kept open for him. Thousands of soldiers were still filtering up northern waterways—including two additional brigades from Cambridge—but most were still weeks from Quebec. The army remained too weak for a direct coup de main. Thomas tried the fireship on May 3, with soldiers formed for an assault if it disrupted the enemy, but the ship failed to reach its target. Two days later, with the British relief fleet’s arrival imminent, the major general conceded that the Americans had decisively lost the race for Quebec. Thomas, not Wooster, ordered the army’s retreat to more defensible ground, forty miles closer to Montreal, sending Wooster ahead to prepare the new site. The Connecticut brigadier just happened to be leaving the next morning, May 6, as the first British ships sailed up to Quebec City.[20]

The Continental camp was already in tremendous disarray with the withdrawal orders, so when British and Canadian Loyalist troops marched out of city gates later that day, the American army fled in panic toward Montreal. Word of this second American catastrophe at Quebec—an outright embarrassment in this case—spread like wildfire all the way to the Continental Congress. Any favorable accounts of Wooster’s army leadership through April were totally eclipsed by news of this shameful flight.

In Philadelphia, six hundred miles from the scene, congressmen rushed to place blame. Montgomery was already a martyr, Schuyler too remote from Quebec, and Thomas had arrived too late and was soon dead of smallpox. So, David Wooster, with his problematic reputation and four months of command in Canada, was the obvious scapegoat for the Quebec collapse and the campaign’s ultimate failure. Well before substantive details came from Canada, Congressional delegates hastily declared “old Wooster has abominably misconducted himself in Canada,” that he had “the credit of this misadventure,” and that “Genl. Wooster, an old woman, suffer’d himself to be surprised by a reinforcem[en]t. that arrived there.” Within days, another report fanned these flames, as Congress’s commissioners in Canada explicitly declared, “General Wooster is in our opinion unfit, totally unfit, to Command your Army & conduct the war.” The commissioners’ early prejudices against the general were undoubtedly amplified by Schuyler on their way into Canada. Furthermore, they arrived there too late to meet Wooster before the May 6 disaster, they never got within one hundred miles of Quebec and appear to have only heeded voices that confirmed their biases. The commissioners recommended Wooster’s immediate recall and Congress quickly issued the requisite orders.[21]

A few American leaders challenged this rush to judgment. New Hampshire’s William Williams wrote “Poor Wooster[,] a worthy Officer is neglected[.] boundless Efforts have been used to blast his Character in Congress by one of the Canada Commissioners.” John Adams observed that the general’s most relentless accusers were the same men whose legislative neglect had undermined the Canadian campaign, and he identified an anti-New England bias behind the movement as well. Widely voicedopinions, however, still held that Wooster was at fault. Unpopular men make convenient marks for blame.[22]

Wooster returned from Canada hurt by the “unjust severity and unmerited abuse” to his character. He requested an examination of his conduct so he could be “acquitted or condemned upon just grounds and sufficient proof.” Congress approved. A committee received testimony and examined all the general’s correspondence before issuing its August 17 report.[23]

It was the “opinion of the committee, upon the whole of the evidence that was before them, that nothing censurable or blameworthy appears against Brigadier General Wooster.” Congress ultimately agreed to the report, but not without “a great struggle.” John Adams wrote that “there was a manifest Endeavour” by the anti-New England contingent “to lay upon [Wooster] the blame of their own misconduct in Congress in embarrassing and starving the War in Canada.” In his view, “Wooster was calumniated for Incapacity, Want of Application and even for Cowardice, with[out] a Colour of Proof of either.”[24]

The report technically cleared David Wooster’s name, but could not overcome the reinforced prejudices against him. While he retained his commission, he did not receive another Continental command, so he returned to Connecticut militia duty. On May 2, 1777, one year after being relieved by Thomas at Quebec, Wooster met a hero’s death from wounds suffered at Ridgefield while leading militia to oppose a British raiding force.

When early Revolutionary War historians reflected on the Canadian campaign’s failure, instead of faulting Wooster or any individual, they offered comprehensive judgments like “The reduction of Quebec was an object to which [the Americans’] resources were inadequate.” The mid-eighteenth century ushered in a new historiographical turn, though—concepts like the “Great Man Theory” and “Manifest Destiny” fostered a new demand to blame someone for the massively failed American opportunity in Canada. Historians began blaming Wooster, relying largely on the preliminary, prejudiced, scapegoating judgments from the summer of 1776, favoring colorful quotes and anecdotes over contextual analysis. According to a medley of these harshly critical accounts, “Wooster did nothing”; he seemed “to have had almost no power of initiative, perhaps none whatever”; he “was incompetent—and did not recognize his own incapacity”; he was an “irascible muddler” and “an arrogant, despotic Yale graduate in a large gray periwig.”[25]

A fair reading of the documentary record, including Wooster’s extraordinary efforts to keep his army outside Quebec, would suggest that Congress’s exoneration and John Adams’ defense offer more accurate assessments of the heavily-criticized general’s performance in Canada. Dealt a losing hand from the start, he never realistically had the resources or guidance to achieve any other strategic or operational outcome, but diligently bought all the time possible for others to deliver what was needed. Contrary to contemporary and historical caricatures, David Wooster demonstrated skilled generalship outside Quebec, maintaining army strength against enormous obstacles in the critical month of April 1776, even if in hindsight the entire campaign’s fate had already been determined by external factors.

[1]“Biography of David Wooster,” American Historical Magazine1, no. 1, (January 1836): 5.

[2]Philip Schuyler to George Washington, October 26, 1775, Philander Chase, ed. The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1985),2: 240-42 (PGWRWS0; John Adams to Joseph Warren, July 23, 1775, Paul H. Smith, ed. Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789(Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1976-2000), 1: 651 (LDC).

[3]David Wooster to Washington, January 21, 1776 and Schuyler to John Hancock, January 29, 1776, Peter Force, ed. American Archives, Fourth Series (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1837-1853),4: 796-97 (AA4), 880;Arnold to Wooster, January 2 and 4, 1776, AA44: 670-71, 854; Wooster to Schuyler, January 5, 1776, AA4 4: 669.

[4]Wooster to Schuyler, February 14, 1776, AA4 4: 1002; A Return of the Forces … in camp before Quebec, February 18, 1776, March 7, 1776, i170 r189 v1, p348, RG360, M247, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

[5]Wooster to Schuyler, January 5, AA44: 1002, and March 16, 1776, AA45: 868-69; Wooster to Washington, January 21, 1776, AA44: 796-97; Wooster to Hancock, February 13, 1776, AA44: 1132; Wooster to Schuyler, March 16, 1776, AA45: 868-69; Washington to Wooster, January 25, 1776, and Schuyler to Wooster, January 25, 1776, AA44: 876-77, 1004.

[6]April 1, 1776, Caleb Haskell’s Diary, Kenneth Roberts, ed., March to Quebec: Journals of the Members of Arnold’s Expedition (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1947), 493; Return of the Troops before Quebeck, March 30, 1776, AA4 5: 550; March 30, 1776, Jean-Baptiste Badeaux Journal, and William Goforth to John Jay, April 8, 1776, Mark R. Anderson, ed., The Invasion of Canada by the Americans, 1775-1776: As Told through Jean-Baptiste Badeaux’s Three Rivers Journal and New York Captain William Goforth’s Letters, trans. Teresa L. Meadows (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2016), 91, 136.

[7]Notes on Captain Hector McNeill’s, Doctor Coates’s, and General Wooster’s Testimony Before the Congressional Committee Investigating the Canadian Campaign, July 2 and 4, 1776, Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1950-), 1: 435-37, 445(PTJ); Arnold to Schuyler, April 20, 1776, AA45: 550.

[8]Richard Montgomery to Schuyler, November 13 and 24, 1775, AA4 3: 1603, 1694-95; Address to the Army, November 15, 1775, AA4 3: 1683-84.

[9]Washington to Joseph Reed, November 28, 1775 and February 10, 1776, PGWRWS 2: 448-51, 3: 286-91; Washington Circular to the New England Governments, December 5, 1775, AA4 4: 191.

[10]Jonathan Trumbull to Washington, December 7, 1775, AA4 4: 213; Schuyler to Hancock, January 22, 1776, William B. Clark, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 1964-), 3: 918 (NDAR); Moses Hazen to Philip Schuyler, April 1, 1776, AA4 5: 751.

[11]An Aged Subscriber [Nathan Beers], “Anecdotes of Gen. Wooster,” American Historical Magazine 1, no. 2 (February 1836): 57; April 9, 1776, “Journal of the Most Remarkable Events Which Happened in Canada,”99-100, MG23-B7, Library and Archives Canada,” 94; McNeill’s Testimony, July 2, 1776, PTJ1: 435; Journal of Dr. Isaac Senter, Roberts, March to Quebec, 237.

[12]April 8, 1776, General Orders, Doyen Salsig, ed., Parole: Quebec; Countersign: Ticonderoga, Second New Jersey Regimental Orderly Book 1776 (Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Press, 1980),58-59, 70, 78-79 (General Orders); Wooster to Hancock, April 10, 1776, AA4 5: 846.

[13]April 13, 1776, General Orders, 75; Notes on Major Samuel Blackden’s Testimony, July 6, 1776, PTJ1: 446; Mathew Mason, S13867, p4, RG15, M804, NARA; Goforth to Alexander McDougall, April 21, 1776, Anderson, Invasion of Canada, 144; Haskell’s Diary, 494-96.

[14]General Orders, April 14 through 16, 1776, 76-78;April 15 and 17, 1776, “Adjutant Russell Dewey Declaration,” in Louis M. Dewey, Life of George Dewey, Rear Admiral, U.S.N. and Dewey Family History (Westfield, MA: Dewey, 1898), 270.

[15]April 18 and 25, 1776, General Orders, 80; April 18, 1776, “Journal of the Seigeof Quebec, 1775,” 32-33, MS Sparks 42, Houghton Library, Harvard University; April 17, 1776, “Dewey Declaration,”270; McNeill’s Testimony, July 2, 1776, PTJ1: 435-36; April 25, 1776, Journal in Daniel Kimball, W15001, p17, RG15, M804, NARA.

[16]April 18, 1776, General Orders, 80.

[17]April 18, 1776, Haskell’s Diary, 494-95; John Jay to Edward Rutledge, July 6, 1776, The Selected Papers of John Jay, ed. Elizabeth M. Nuxoll (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010), 1: 263–65.

[18]April 28, 1776, General Orders,91; April 29, 1776, Haskell’s Diary, 494-96; McNeill’s and Blackden’s Testimony, July 2 and 6, 1776, PTJ1: 435-36, 446; April 30 and May 1, 1776, Badeaux Journal, Anderson, Invasion of Canada, 125, 146.

[19]McNeill’s and Doctor Coates’s Testimony, July 2, 1776, PTJ1: 435-37.

[20]John Thomas to Arnold [May 2?] in Arnold to Schuyler, May 6, 1776, Philip Schuyler Papers, New York Public Library; Wooster’s Testimony, July 2, 1776, PTJ1: 445; Thomas to the Commissioners, May 7, 1776, NDAR 4: 1433, 1435.

[21]Richard Henry Lee to Charles Lee, May 18, 1776, Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Nelson, May 19, 1776, Francis Lightfoot Lee to Landon Carter, May 21, 1776, Commissioners to Hancock, May 27, 1776, Hancock to Washington, June 7, 1776, LDC 4: 36, 39-40, 58, 81, 156-57.

[22]John Adams to James Warren, May 18, 1776, and William Williams to Joseph Trumbull, August 10, 1776, LDC 4: 32, 650-51.

[23]Wooster to Hancock, June 26, 1776, AA46: 1081.

[24]August 17, 1776, Worthington C. Ford, ed. Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington, DC: 1904-37)5: 664-65; August 17, 1776, Diary of John Adams, L. H. Butterfield, ed., The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961), 3: 409.

[25]Early works include David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution (1794) 1: 342 and John Marshall, The Life of George Washington … (1805), 2: 324-25. Wooster-blaming works include George Bancroft, History of the United States … (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1860), 8: 419; Robert Tomes, Battles of America by Sea and Land. Volume 1: Colonial and Revolutionary (New York: Patterson & Neilson, 1878), 261; Justin H. Smith, Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony: Canada and the American Revolution (New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1907),2: 590, note LXXXIII; Carl Van Doren, Secret History of the American Revolution (New York: Viking Press, 1941), 151; Robert Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 346; Gustave Lanctot, Canada and the American Revolution, 1774-1783, trans. Margaret Cameron (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967), 137; Rick Atkinson, The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777 (New York: Henry Holt, 2019), 277. For other aspects of Wooster’s controversial command, see Mark R. Anderson, The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony: America’s War of Liberation in Canada, 1774-1776 (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2013), 209, 359-60.

9 Comments

Good article Mark. I have thought for a few years that although Wooster’s career suffered from some of his actions or inactions during the Revolution there should be at least one published biography about his life. The only one that has ever been written had two books actually printed. One of the two is in the Cheshire Connecticut Historical Society Library. It needs to be updated but could serve as a basis for his bio.

He did serve in the military for more years than most generals. The decision by the Continental Congress Committee in Canada to relieve him of command definitely had an impact on his reputation. I hope someone will step up to the plate and do the work to present his life.

Steve

I agree with you that a full-length Wooster bio is needed. I came across a 2018 partial bio entitled “Wooster’s Invisible Enemies,” by Brian S. Barrett. It’s a self-published volume covering Wooster’s early participation in the Revolution through the Canadian campaign. I have not analyzed Barrett’s work, but maybe Mark has an opinion on its merits. Barrett’s book is available on Amazon. Gene

Mark, Nice account of Gen Wooster’s delaying tactics to carry on the siege of Quebec during early 1776. He was a prickly commander and rubbed Gen Schuyler the wrong way. However Montgomery respected his leadership and entrusted him with command at Ft St Johns during late 1775. He was a notable leader under adverse conditions.

Thanks for the kind words Brian, Gene, and Steve. It would be nice to have a comprehensive Wooster biography, and since he never served directly with Washington, Wooster’s been neglected in almost every study on “Washington’s generals.” Brian Barrett’s “Invisible Enemies” is generally focused on the medical challenges that Connecticut troops faced early in the war, and nicely captures some of Wooster’s no-win and self-inflicted leadership episodes that contributed to his unpopular reputation—especially in the summer of 1775.

Apparently, I have the only other published copy of George O. Ellis’s Wooster biography – I managed to get it secondhand after the Cheshire Public Library removed it from its collection. For the most part, it is a compilation of transcribed Wooster primary source material, knitted together with chronological narrative. Most of the correspondence in it is captured in other more common sources, like Force’s American Archives. It’s helpful for putting Wooster’s life together in the big picture, but it is short on context and analysis, and its often-absent source citations are a real weak point.

Excellent article Mark. My ancestors lived in Quebec and on the islands in the St. Lawrence during this time. They would have seen all these soldiers floating down the river. – Karen in Canada

My 4th great grandfather, Caleb Haskell, was at Quebec as part of the Arnold Expedition. As you know, he kept a diary, and I think it provides some insight into General Worcester’s [sic] methods of keeping men at the siege, even after their enlistments had expired on December 31.

Here are a couple of pertinent entries (besides “The General desires we stay a few more days”:

“January 30th, Tuesday [1776].

This day we had to go down the Bon poir ferry and join Capt. Smith, which was not agreeable to our company, we looking upon ourselves as freemen, and, have been so since the first of January, refused to go. Our company consisting of fourteen men fit for duty enlisted for two months under Capt. Newhall in Col. Livingston’s regiment. In the afternoon were put under guard at head quarters for disobedience of orders.

January 31st, Wednesday.

Today we were tried by a Court Martial, and fined one month’s pay, and ordered to join Capt. Smith immediately, or be again confined and receive thirty-nine stripes; two minutes allowed to answer in. We finding that arbitrary rule prevailed, concluded to go with Capt. Smith. Then we were released and went to our quarters.”

I’m getting a t-shirt with “Arbitrary Rule Prevails” in honor of the Good General’s tactics.

I have another 4th great grandfather, Dr. Azor Betts, who was a Loyalist and is mentioned on the site Founders Online in the entry “General Orders, 26 May 1776”, and also in Peter Force’s American Archives. I feel that my once all-admiring concept of “Patriots” has been irreparably tarnished. I’m still proud of my ancestors, though.

The troops whose enlistments had expired on December 31, 1775 couldn’t leave because of the weather (and some were still sick with smallpox), so Wooster had Arnold court martial them and threaten them with corporal punishment to get get them to reenlist again. Arbitrary rule prevails (I just had that put on a t-shirt). Creative tactics. Great general.

January 30th, Tuesday.

This day we had to go down the Bon poir ferry and join Capt. Smith, which was not agreeable to our company, we looking upon ourselves as freemen, and, have been so since the first of January, refused to go. Our company consisting of fourteen men fit for duty enlisted for two months under Capt. Newhall in Col. Livingston’s regiment. In the afternoon were put under guard at head quarters for disobedience of orders.

January 31st, Wednesday.

Today we were tried by a Court Martial, and fined one month’s pay, and ordered to join Capt. Smith immediately, or be again confined and receive thirty-nine stripes; two minutes allowed to answer in. We finding that arbitrary rule prevailed, concluded to go with Capt. Smith. Then we were released and went to our quarters.

(Caleb Haskell’s Diary)

Les,

“arbitrary rule prevailed” indeed, and it was clearly unjust for those men who had already sacrificed so much to be forced to serve beyond their terms. However, the Northern Army chain of command agreed to its necessity. Having already received Arnold’s recommendation, Wooster reported to Schuyler, “I have given orders to suffer no men to go out of the country, whether they will inlist or not; the necessity of the case, I believe will justify my conduct”; and even though Schuyler had many issues with Wooster on other points, he replied on January 14, “I am very happy that you have issued orders not to let any men depart, although the term for which they are inlisted is expired. You may rest assured, sir, that a conduct so prudent, will meet with the fullest approbation.”[see note 3 in the article for citations] Schuyler, in turn, reported this to Congress—and even after a committee reviewed the correspondence in detail, no one seems to have taken issue with the arbitrary measure, and no direction came from Philadelphia to criticize or overrule it [JCC 4: 123, 154-55 and time-relevant letters of delegates]. They were truly desperate times. I didn’t delve deep into this issue in the article, because its focus was on the April-May period, when Wooster became directly involved in day-to-day events at Quebec.

Now at the risk of quibbling over the details of what the sources say, the extant correspondence clearly shows that Wooster supported Arnold’s choice to keep men past their terms, but he didn’t tell Arnold how to do it—the regular tools of military discipline could, of course, be assumed. Wooster didn’t have a direct hand in dispensing justice at Quebec until he arrived in April. In Haskell’s text, it’s also notable that he doesn’t mention any issue with being ‘extended’ until almost a month after his enlistment was complete, and weeks after recovering from small pox; and that only came out in the context of refusing orders that he and his company cohort found “not agreeable” (to join Capt. Smith at the ferry). Such an act of ‘arbitrary insubordination’ was a direct threat to military order at Quebec—thus prompting the confinement, court martial, fines, and the threat of flogging that Haskell describes, executed under Arnold’s local command authority.

Voluntary military service is contractual, so it’s a type of indentured servitude. These freemen were conscripted, illegally detained, and held as slaves after their enlistments expire. But I guess since it was a military necessity, that justifies it. Because America. American rule prevails.