It is often believed or reported that the 2nd New York Regiment of 1775, commanded by Col. Goose Van Schaick, morphed into the 1st New York that started late in 1776 as part of the third establishment of the Continental Army. This unit would continue through the derangement (better known today as “downsizing”) of the New York Line in 1780 to end up mustering out at the New Windsor Cantonment in 1783.

In 1987, these thoughts were reinforced by author and researcher Robert Wright, Jr., who writes that the 2nd New York of 1775 was “reorganized and redesignated 15 April 1776 as Van Schaick’s Regiment”and was “consolidated 26 January 1777 with the 4th New York . . . as the 1st New York Regiment.”[1] This theory appears to be predominately based on the career of Colonel Van Schaick and not on historical facts or documentation. In fact, it is wrong.

Following the fall of Montreal on November 13, 1775, the New York troops in the forward areas were significantly reorganized. Most of these men agreed to stay in the service for five to six months longer rather than finish out their current enlistments.[2] Despite attrition having taken its toll and many men in the rear areas mustering out, the New York battalions retained their original designations until the spring of 1776. Command of the “Second Battalion of Yorkers” was left to the ranking officer in the regiment, its senior captain, John Visscher.

Meanwhile, Colonel Van Schaick, Lt. Col. Peter Yates, and Maj. Peter Gansevoort had left the 2nd New York and were given command of a new battalion on January 8, 1776, by the New York Provincial Congress.[3] This new unnumbered regiment became known as Van Schaick’s Battalion.[4] In addition, the Continental Congress ordered New York to raise four new battalions, as part of the army’s second establishment, for its own defense.[5]

By the end of March 1776, the Colony of New York had on the books the remnants of their original four infantry battalions, Van Schaick’s Battalion, and the four battalions being raised for the defense of New York City. However, come mid-April, the original four regiments had withered away. Those officers and men who had wished to stay in Canada were formed into a new battalion under the command of Col. John Nicholson, a former company commander with the 3rd New York.[6] This meant that for a few weeks, New York had ten regiments in service with the Continental army.

If the logic of the lineage supporter is to be believed, Colonel Van Schaick should have drawn on the more active front-line company officers when forming his new battalion.That was not the case, because he formed his battalion in early 1776 and those officers were technically still with their original regiments until springtime. The facts are that most of the officers in Van Schaick’s (unnumbered) Battalion came from the other former New York regiments and even some from Connecticut. The handful of its officers that had previously served with the old 2nd New York were among those that ended their enlistments at the end of 1775.[7] By no means could any of this be considered a form of lineage.

The original 2nd New York in 1775 had 758 officers, staff, and enlisted men on the books. As of this writing, I have uncovered 613 names using existing muster rolls, subscription lists, internet searches, and assorted cross-references. Of these, 172 have detailed information about their service, acquired from federal and state pension applications, biographies, family histories, or other confirmations. Only 74 of them have any confirmed service in the Continental Army (excluding regular militia, ad-hoc militia [levies], and the state troops which New York inexplicably also called “levies”) beyond the 1775-76 Canadian campaign. That breaks down to forty-three percent of those with detailed stories and just about ten percent of the total number of members in the regiment in 1775.

To further tear down the legacy theory: of those 172 names with detailed stories, none of them have been found to have served in any of the four New York regiments formed as part of the second establishment of the Continental Army in 1776. Starting in 1777, just twenty-one (including ten officers[8]) have been found to ever serve in the 1st New York after the third establishment of the army was formed in late 1776.

Some of the longer individual stories of the 169 men have already been presented here in the Journal of the American Revolution.[9] The following are three shorter stories of the twenty-one men who actually went on to serve in the 1st New York’s third establishment. All three were enlisted men and each would become a Federal pensioner due to being indigent:

William Dickens (1750–1819)

Dickens was one of the longest-serving private soldiers in the Continental Army.[10] He is listed, on what is known as a subscriber’s list, as one of Capt. John Visscher’s newly-recruited Albany County Provincial company on June 3, 1775.[11] This was the first company of soldiers raised in the defense of the colony and was sent to secure Fort Ticonderoga after its capture by the Green Mountain Boys on May 10.[12] This company would soon become part of the 2nd New York Regiment.[13]

In his Federal pension application deposition, sixty-eight-year-old Dickens states he had enlisted in 1775 in Albany, New York, for six months in Capt. Benjamin Evans’ company of Goose Van Schaick’s regiment. This is clearly a lapse of memory, because Benjamin Evans was 1st lieutenant of Visscher’s company. Dickens was probably enlisted by Evans when he was out recruiting for the company.[14]

Dickens only briefly explained in that deposition that he “went to Canada,” and was “in the Battle of St. Johns” and “in the Battle when Genl Montgomery was killed at Quebec.”[15] This allows the extrapolation that he extended his enlistment and continued with the company until the spring.

In April 1776, Dickens explained that he returned to Albany and enlisted into the 1st New York under Capt. John Graham.[16] At that time, Graham was actually captain of the 3rd company of Col. John Nicholson’s Regiment.[17] Dickens likely enlisted there and just “shipped over” to the 1st New York when Captain Graham went over to the new 1st New York as part of the third establishment of the Continental Army.

While he was with the 1st New York, Dickens took part in the “taking of Burgoyne,” the Battle at Monmouth Courthouse, and the “taking of Corn Wallace.”[18] Dickens further describes that while stationed at Fort Stanwix (Schuyler) he was wounded in the breast by a musket ball shot by Indians. The ball remained lodged in his backbone; incredibly, he served until the end of the war. He made no disability claim thereafter.[19]

Further investigation into his actual service shows he was transferred into the regiment’s light infantry company in March 28, 1779.[20] He finished out the war there.[21] For that period, none of the known existing muster rolls indicate his chest wound or any extended hospital stay. This suggests it happened prior to his transfer. It also means that he probably took part in the famous attack on Redoubt 10 during the siege of Yorktown with a lead bullet lodged in his spine!

In his Federal pension application in April 1818, Dickens also explained that he was “in reduced circumstances & stands in need of the assistance of his Country for Support.” Consequently, he was awarded a pension of eight dollars a month, plus arrears for his service. Dickens passed away on August 24, 1819.[22] The 1820 list of federal pensioners under the Act of March 18, 1818 is annotated accordingly.[23] There is no record of either Dickens or his heirs receiving any of this money.

Dickens was an illiterate man, as he made his mark on both Visscher’s list back in 1775 and his Federal pension application deposition in 1818.

John Rose (1746–1833)

John Rose is one of the most impressive of the known enlisted me to serve in the regiment. His incredible story covers all but about six weeks of the war. It is an adventure that is exciting, confusing, and often uncorroborated.

A Federal pensioner, Rose submitted two depositions to explain his long service. The first was dated April 9, 1818 and signed by him. Here he describes what he initially did in the war:

in the month of June 1775 I enlisted for six months in Captain Cornelius Van Dyck’s Company of Col. Gosa Van Scahick’s Regiment of the New York troops, which time I served out and again to wit about the tenth day of January in the year of our Lord 1776 I enlisted for six months into Captain Fisher’s Company of the same Regiment as above, which time I also served and afterward remained with the army as a volunteer until Genl. Burgoyne came down to Saratoga when to wit about the fifteenth day of September 1777.[24]

His second deposition, dated September 28, 1830, was apparently submitted with support documentation for the earlier application. In it, he describes his early war service a bit differently:

he enlisted in the Army of the Revolution in June 1775 in Capt. Cornelius Van Dykes Company for the term of six months—was at the siege of St. Johns–That he went from there as a volunteer with Ethan Allen and was taken prisoner on the Island of Montreal—that he jumped overboard from the Gaspee Frigate Schooner swam ashore and again joined the army under Gen. Montgomery—That he was at the siege and at the storm of Quebec & was there wounded in the arm—That he again enlisted for six months in Capt. McCrackens Company & remained in the army until Gen. Burgoyne came down from Canada”[25]

Between these two depositions there are several inconsistencies. Some are explainable, but others are problematic. First of all there is no known surviving muster roll for Van Dyck’s company. There is a small subscriber list for Van Dyck’s provincial company, but Rose is not listed. Others on the list signed it later than Rose claimed he enlisted.[26]

There is no explanation of how Rose was able to leave Van Dyck’s company and go with Allen. Yet, if he went into Montreal, he would have been captured along with Allen. Since these prisoners were sailed to Quebec, he could have jumped ship. The biggest questions, are, when did the Gaspee sail and when did Rose make his desperate escape?

Without that information, timing can still be narrowed slightly. Allen and his men were captured on September 25. Montreal would ultimately fall to the Congressional forces on November 13. At that same time they, ironically, captured the Gaspee. Figuring a few days on either end for travel or other matters, it is a good estimate that John Rose jumped the Gaspee between September 28 and November 10, 1775.

After reorganizing the army for the coming winter, Montgomery’s advance force did not embark from Montreal for Quebec until November 28 “on board the Gaspee Sloop of war and the Mary Schooner.” Among them was one reinforced company of the 2nd New York commanded by Capt. John Visscher (Fisher).[27]

A transcribed muster roll of Elisha Benedict’s Company of the 2nd New York includes John Rose. It notes twelve of the men as being “on Command Quebec,” but Rose was not one of the twelve.[28] It is believed these men were temporarily transferred to reinforce Visscher’s company for the assault. Since Rose stated he was in Quebec for the assault and never mentioned Captain Benedict in any deposition, this soldier was probably a different John Rose. This would not be the only time another John Rose would come up.

Van Dyck’s company of the 2nd New York was only around for six months, so any of the men who wished to stay in the service became sort of free agents to join whatever company they wanted. Rose was one of these men, but would not have joined Joseph McCracken’s Company, because, like Van Dyck’s, it folded before the end of 1775. Many of its members became free agents filling in gaps in the rolls of the other companies.[29]

By accepting that there was a second John Rose, the differing depositions are more plausible when combined: after returning to the regiment from captivity, Rose joined Visscher’s Company for its extended six months, took part in the assault and was wounded.[30] When the six months were up, which would be about May 1776, Rose could have joined McCracken’s new company for six months. This would bring him to the late fall 1776.

The rest of John Rose’s service was in the 1st New York Regiment in the third establishment of the Continental Army beginning in November 1776. It is more easily understood and the two depositions are reasonably consistent. He described those years best in his 1830 deposition:

enlisted at the Saratoga Barracks to serve during the war—That he remained in the Army until General Burgoyne was taken & then went with Gen. Sullivans expedition—Was afterwards at the battle of Monmouth in New Jersey and was there wounded in the throat. That he served under different Companies Captains until the year 1783—Between the years 1780 & 1781 he was transferred to Capt. Aaron Austin’s Company—was in the battle of Yorktown & there had his leg broken by a Bombshot—that he remained in the army until it was disbanded & received an honorable discharge at Snake Hill 1783 in Orange County New York . . . That he received a Sergeants Warrant in 1778 & served as a Sergeant in the army & at several times as a Recruiting Sergeant—& this deponent says that he never deserted the colours of his country[31]

Rose’s pension application included three supporting testimonials. All stated the usual, that he was an esteemed, faithful, and good soldier. One of the deponents was John N. Lighthall, one of Van Dyck’s subscribers and a member of that company in the 2nd New York, who ultimately ended up mustering out of the 1st New York at the same place as Rose.[32]

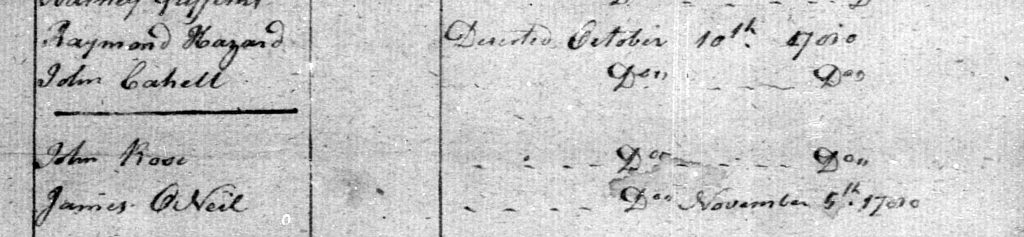

There was enough documentation to allow the War Department to grant Rose a basic pension of eight dollars per month, starting in September 24, 1818.[33] However, by about 1830, that pension was suspended because of questions raised regarding his supposed desertion.[34] An April 1830 memo on file with the Treasury Department indicates this line of thought. It seems to have never occurred to the clerk that there might be some muster rolls that the Treasury Department did not have or that there could be more than one John Rose:

It appears from the Muster Rolls in this Department of the 1st New York Regiment that John Rose enlisted in Captain Copp’s Company on the 26th November 1776 for the war and remarked opposite his name “Deserted 10th October 1780.” His name does not again appear on the Rolls of the New York Line.[35]

The good news for Rose was that by autumn, his representatives had some additional corroborating evidence put into the record in the form of depositions. The first was given by John Folligard, a former enlisted soldier in the 2nd New York of the third establishment, to a phonetically-spelling transcriber on September 23 confirming that Rose was:

in the Battel of the Taking of Genl Burgoine at Saratoga. In 1780 I certify that I knew John Rose as a Recruiting Sargent at Morristown New Jersey in Capt. Aaron Austins Company first New York Rigement and I further Certify that in 1782 at the Ballel of York Town where Lord Corn Wallace was Taken that he John Rose was in the army under Captain Aaron and their got his Leg Broken By a Bombshell and I further Certify that he John Rose was in the army in 1783 at Snake Hill Orange County State of New York and got his Discharge in June 1783.[36]

William Waddle enlisted as a member of the 3rd New York prior to the derangement (downsizing) of the New York Line. He made a deposition on September 25, 1830 where he explained:

That between the years 1780 and ‘81 he was transferred to Capt. Aaron Austin’s Company in which company he remained during the war—in the 1st New York Regiment—That at the time he was attached to said company John Rose was a Serjeant in said company—That he saw said John Rose on duty (except when he left the Company occasionally as a recruiting Serjeant) almost daily—That he was with him and they were discharged at the same time at Snake Hill Orange County State if New York on the 8th June 1783.[37]

John C. Ten Broeck, a former captain in the 1st New York, who served to the end of the war, confirmed Rose’s broken leg at Yorktown in a deposition dated September 27 where he stated that he:

knows the said John Rose to have been in the servis in the engagement at York Town against Lord Corn Wallace and that the said John Rose got his Leg Broke in the Servis and always Bore the Character of a Good and faithfull Soldier and that he has Never known the Said John Rose to have Deserted.[38]

John Wendell, who was another captain in the 1st New York, made the following statement in September 1830:

a soldier in his command by the name of John Rose served in his Company part of the time, and was drafted into the [Light] Infantry Company . . . that Rose bore the character of a good and faithfull Soldier, that I have understood he Served ‘till the time the Army was disbanded where he was discharged & has drawn a Pension for his good Services to the 4th March 1830 and further that I never heard that he deserted.[39]

A month later Wendell made a second sworn statement that explained what happened to the enlisted men in the 1st New York after the derangement of the New York Line:

I certify that John Rose in the Revolutionary War was transferred from Captain Copp’s Company in the first NYork Regiment to my company after the five regiments were consolidated into two regiments, which was in the year 1780, when Captain Copp was one of the Captains who retired & the men were transferred to the different companies of the regiment who continued. Given under my hand at the City of Albany this 25th day of October 1830.[40]

This onslaught of witnesses must have been sufficient to turn the tide. On January 25, 1831, the suspension of Rose’s pension was removed.[41] The last payment of $8.00 was made to his attorney on September 4, 1832. The record noted that he passed in 1833.[42]

William Turnbull

Like William Dickens, William Turnbull was a member of John Visscher’s 2nd New York Company in the spring of 1775. However, he was not included on the list of Visscher’s subscribers that was made on June 3. Since Turnbull does not mention it in is federal pension application, he probably was not involved in the relief of Fort Ticonderoga.

As a member of Visscher’s company, Turnbull was with Montgomery in the Assault on Quebec and continued as a private soldier with the company on an extended enlistment until April 1776. He stayed in Canada with a six month enlistment in a new company under the command of his old 1st lieutenant, Benjamin Evans, who had been promoted to captain.[43] This company was part of Col. John Nicholson’s (unnumbered) New York Regiment, which was composed of Canadian campaign veterans.[44]

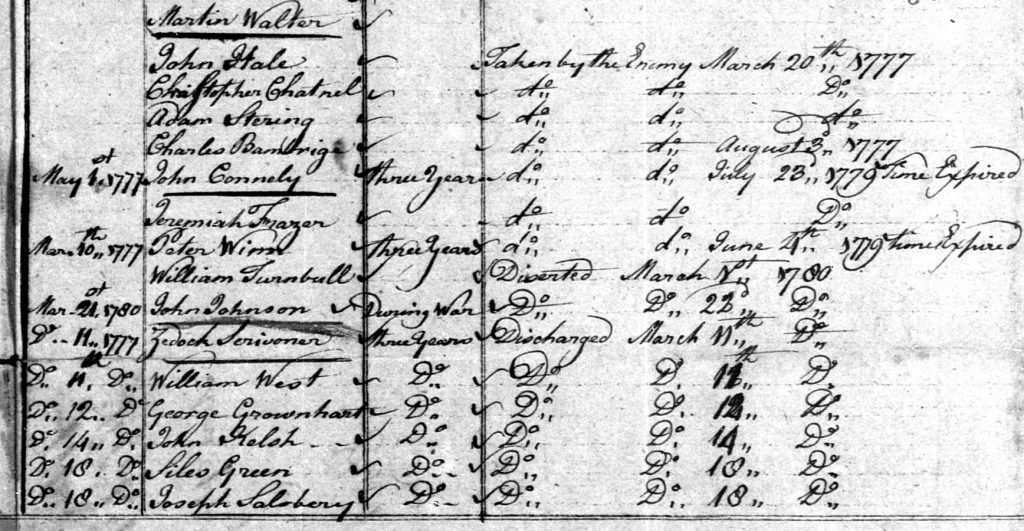

On November 30, 1776, Turnbull enlisted for the duration as a private in Capt. John Graham’s company of the new 1st New York Regiment. This company would later be known as the Lieutenant Colonel’s Company.[45] Turnbull explained his service there, and the frightening experience that ended it, in one of his federal pension application depositions:

I then enlisted under Captain John Graham Colonel Van Schaick’s Regiment in the first Battalion for three years or during the war, was at the Battle of Monmouth in the month of June 1778 and continued in the service until Seventeen hundred and Eighty one when I was taken prisoner and Tomahawked by the Indians under the Command of Captain Brant—That having survived the effects of the Tomahawk and three years bondage among the Savages I fell into the hands of a French Trader near Detroyt and was permitted by him to return to my Country whose army I found disbanded.[46]

Such an account, even a brief one, gives one pause to consider the horror he must have felt of being a wounded captive and taken to a distant part of North America.[47] After getting traded to the trapper, he was released and told, “New York is that way.” Since Turnbull did not mention a horse, he probably did not have one. There were limited roads going east-west, few (if any) bridges, maybe a ferry here and there, and no food or lodging, making such a journey formidable, to say the least. It boggles the mind that Turnbull not only made the trip, but lived many years to tell stories about it.

He had to have had a rough life, however, as he was indigent enough to file for a federal pension. He also stated, without explanation in a later deposition, of an implied tragedy, that he had “no family having lost his wife and five children.”[48] On top of that burden, like John Rose, Turnbull had a desertion problem. Regimental muster rolls indicate that he had deserted on March 1, 1780,[49] and with a name like his, there was little chance of mistaken identity.

Surprisingly, the noted desertion did not seem to cause Turnbull a significant setback in getting a Certificate of Pension issued in his name on October 25, 1818 for eight dollars per month plus arrears.[50] However, he was omitted from the official 1820 pension list.

There is no copy in the file of any letter back to Turnbull’s representatives requesting supporting documentation, but something happened. Fourteen months after the certificate was issued, Abraham Ten Eyck, former paymaster of the 1st New York when Turnbull was with them, gave a deposition for him. He stated that upon an inspection of the payrolls still in his possession, William Turnbull was “entered therein during the whole of the year 1779 and the two first two months of the year 1780” and he “appears mostly on the list of Colonel Van Dyck’s Company of said Regiment, but it was a very common thing to transfer from one company to another.”[51]

If the War Department was questioning Turnbull’s suspected desertion, Ten Eyck’s deposition was really of little use. What probably swung any arguments away from a possibility of desertion was John McLean, a pensioner who had also been a member of Capt. John Copp’s company in the 1st New York.[52] McLean made a short deposition on August 21, 1822 and briefly explained he knew him and confirmed that “William Turnbull was taken a prisoner by the enemy.”[53] Given that Turnbull did not return until after the war, the mistake in the roll was never corrected.

Conclusion

By any stretch of the imagination these are three amazing men. Their stories, taken at face value, are almost unbelievable. They had each served for the duration of the war. All were enlisted soldiers; not a commissioned officer among them. They each served in Canada and took part in the assault on Quebec, the Sullivan/Clinton campaign, and the battle of Monmouth Courthouse. Two were at Saratoga, two were at the siege of Yorktown, and two were prisoners of war. All three were wounded by the enemy (one of them three times). Yet, none of them filed a disability claim of any kind.

We have already discussed the odds of a 2nd New Yorker in 1775 to serve past the first year of the war as being rather slim. To have served all eight years was even slimmer. Add to this the probability of living into adulthood in the latter part of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was narrow enough, and living past one’s forties was remarkable in its own right. Add to this the abuse these men’s bodies took during the war with the harsh weather conditions, the wounds from battle, and the effects being held in captivity, all one can do is look back in awe at them and feel very proud indeed.

[1]Entry for the 1st New York Regiment, The Continental Army, Robert K. Wright Jr. (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 247.

[2]Entries for November 14, 1775, “Journal of [Lt.] Col. Rudolphus Ritzema of the First New York Regiment, August 8 1775 to March 30 1776, from the original in the Collection of the New York Historical Society,” Magazine of American History With Notes and Queries, 1 (1877), 103, (“Journal of [Lt.] Col. Rudolphus Ritzema”). There is also evidence among the muster rolls and pension records of a number of Yorkers men migrated into the Connecticut forces, which were also going through their own transition to the new establishment.

[3]Congressional Resolution, January 8, 1776, Berthold Fernow, ed., Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New York (Albany, NY: Weed, Parsons and Co., 1853–1887), 15:45-46, (Documents Relating).

[4]Researchers often confuse this new battalion with Van Schaick’s former command, or presume them to be one in the same. During the American Revolution, a regiment could have more than one battalion, but the overwhelming majority only had a single battalion. As a result, the terms battalion and regiment were often used interchangeably.

[5]Congressional Resolution, January 19, 1776, Fernow, Documents Relating, 15:47.

[6]Congressional Resolution, January 8, 1776, ibid, 45. The latter portion of this resolution does not specifically name Nicholson, only “that two Battalions be formed out of the troops now in Canada.”

[7]Muster Roll of the Field, Staff, and other Commissioned Officers in Colonel Goose Van Schaick’s Battalion of Forces . . . , December 17, 1776, Muster Rolls, Roll 77, Folder 163, (Officers in Colonel Goose Van Schaick’s Battalion).

[8]The ten were Col. Goose Schaick, Quartermaster Van Woert, Captains Van Dyck, Yates, McCracken, and Graham, 1st Lieutenant Finck, and 2nd Lieutenants Van Rensselaer, Van Veghten, and Young.

[9]allthingsliberty.com/2017/03/henry-defendorff-intelligent-man/,allthingsliberty.com/2018/02/hard-service-sufferings-james-dole/,allthingsliberty.com/2017/11/evans-bean-hampshire-grants/,allthingsliberty.com/2019/05/the-court-martial-of-captain-joel-pratt/,allthingsliberty.com/2016/10/worthy-troubled-continental-service-capt-barent-j-ten-eyck/,

[10]Dickens would serve for the entire eight years of the war. He enlisted about a week or so before the Battle of Bunker (Breed’s) Hill and mustered out in 1783 at the New Windsor Cantonment. This was about six months longer than the famous Private Yankee Doodle, Joseph Plumb Martin.

[11]Capt. John Visscher’s subscribers, June 3, 1775, W.21468, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, 1800-1900, Records Group 15 (Washington: National Archives Microfilm Publications, M804), Roll 1440, (Pensions).

[12]Entry for John Visscher, Fernow, Documents Relating, 15:253, 538, 540.

[14]Deposition of William Dickens, April 2, 1818, Pensions (S.43502 Roll 809), (Dickens’s Pension File). It is likely that Dickens skipped over the earlier enlistment in the Albany Provincials, as the companies were essentially one in the same. Evans would also become a captain in Nicholson’s (Unnumbered) New York Battalion in March 1776. Entry for Benjamin Evans, Frances B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April, 1775, to December, 1783, Reprint of the New, Revised, and Enlarged Edition of 1914, With Addenda by Robert H. Kelby, 1932 (Baltimore MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1982), 219.

[15]Ibid. There was technically no battle at St. Johns, only a siege with sorties. He could have also meant other action outside of Montreal. There is no way of knowing.

[17]Arrangement of officers in Col. John Nicholson’s Regiment, April 15, 1776, Revolutionary War Rolls 1775-1783, Records Group 93 (Washington: National Archives Microfilm Publications, M246), Roll 75, Folder 131 (Muster Rolls).

[18]Deposition of William Dickens, April 2, 1818, Dickens’s Pension File. It is interesting that most Federal pensioners invariably reference the “taking of Burgoyne” or the “taking of Cornwallis” instead of the battles of Saratoga (Freeman’s Farm) or Yorktown.

[19]Ibid. The 1st New York was stationed at Fort Stanwix (Schuyler) for nearly two years around 1779‒1780. There are gaps in the known muster rolls, so the exact date when Dickens was wounded is unknown.

[20]Muster Roll of the Lt. Col. Cornelius Van Dyck’s (late Captain Graham’s) Company in the first Battalion New York Forces . . ., Months of January, February, and March 1779, Muster Rolls, Roll 65, Folder 16.

[21]Muster Roll of the Light Infantry Company in the 1st New York Regt of Foot, April 1783, ibid, Folder 6.

[22]Deposition of William Dickens, April 2, 1818, Dickens’s Pension File.

[23]The Pension List of 1820, U.S. War Department (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co, 1991), with new index, originally published as Letter from the Secretary of War, Transmitting a Report of the Names, Rank, and Line, of Every Person Placed on the Pension List, in Pursuance of the Act of 18th March, 1818, &c., January 20, 1820 (Washington, DC: Gales & Seaton, 1820), 373 (The Pension List of 1820).

[24]Deposition of John Rose, April 9, 1818, Pensions (S.43940 Roll 2084), (Rose’s Pension File).

[25]Deposition of John Rose, September 28, 1830, ibid.The Gaspeethat Rosesailed onwas the brigantine built after the customs schooner, of the same name, was burned off the shores of Rhode Island in 1772.

[26]List of Voluntary Subscribers under Captain van Dyke to defend Ticonderoga, May 13, 1775, Willis T. Hanson, Jr. Collection, 1721-1919 (2006.2.4), Schenectady County Historical Society.

[27]Entries for November 28 and December 1, 1775, “Journal of [Lt.] Col. Rudolphus Ritzema,” 103, 104. This company is not specifically named, but other sources have identified this fact. One is a Federal pension application deposition by William Carr, May 17, 1834, Pensions (S.22764Roll 478).Carr was a sergeant in Visscher’s company and “on the evening of the arrival of the army upon the Plains of Abraham [I] posted the first picket guard of the American Army upon those plains.”

[28]A Muster Roll of Captain Elisha Benedict’s Company of the Second Regiment of New York Troops . . . , January 7, 1776, Muster Rolls, Roll 67, Folder 19.

[29]Officers in Colonel Goose Van Schaick’s Battalion. Joseph McCracken would surface again early in 1776 as commander of a new company in this battalion.

[30]Rose might have been wounded at the Point Aux Trembles landing. It is more likely it was during the attack itself where Visscher was ordered to “get some men to remove the groaning Wounded & enable them to Crawle off.” Donald Campbell to Robert R. Livingston, March 28, 1776, Livingston Papers, Transcribed Letter Book, (Hyde Park, NY, Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library, 1937), 3-4.

[31]Deposition of John Rose, September 28, 1830, Rose’s Pension File.

[32]Deposition of James N. Lighthall for John Rose, March 31, 1818, ibid.Lighthall was also a Federal pensioner and this citation is for the deposition he made for that application.

[33]Certificate of Pension for John Rose, September 24, 1818, ibid. The Pension List of 1820, 436.

[34]Deserted, deserter, or desertion are terms commonly referred to today as being absent without leave (A.W.O.L). Though a very serious offense, it happened so often in the Continental Army that there appears to be little or no punishment handed out. If a deserted soldier returned to the army on his own or was re-taken, he could probably return to the ranks, provided he made up the time missed. If, however, the soldier deserted to the enemy and provided information, such as troop strengths, location of fortifications, and the like, that was considered a treasonable offense. In those cases, it was unlikely the deserter would return.

[35]Memo by Francis A. Dickins, Treasury Department Clerk, April 27, 1830, Rose’s Pension File.

[36]Deposition of John Folligard, September 23, 1830, ibid.

[37]Deposition from William Waddle, September 25, 1830, ibid. Waddle was also a Federal pensioner and had his last name spelled several different ways.

[38]Deposition of John C. Ten Broeck, September 27, 1830, ibid.

[39]Deposition of John H. Wendell, September 28, 1830, ibid.

[40]Written statement by John Wendell, October 25, 1830, ibid. Wendell also made an annotation that he resigned his commission “on account of ill health in April 1781.”

[41]Note placed in John Rose’s Pension File, September 24, 18[__], ibid.

[42]Letter from Treasury Department auditor to the Commissioner of Pensions, October 28, 1911, ibid.

[43]Deposition of William Turnbull, April 7, 1818, Pensions (S.42540 Roll 2423), (Turnbull’s Pension File).

[44]List of officers Col. John Nicholson’s Regiment, April 15, 1776,Muster Rolls, Roll 75, Folder 131.

[45]The New York Line, First Regiment, Second Company (later Lieut. Colonels Company), Fernow, Documents Relating, 15: 175, 176.

[46]Deposition of William Turnbull, April 7, 1818, Turnbull’s Pension File.

[47]If not initially killed, many prisoners of the Indians survived and actually thrived in captivity. Many were returned at the end of the war. Turnbull seems to have been one of those, though his physical location made it more difficult. For a brief look at the experience of being captured by Mohawk Indians, please read story of fellow Quebec assaulter Daniel Bean: “Evans & Bean of the Hampshire Grants,” Philip D. Weaver, Journal of the American Revolution, November 2, 2017, allthingsliberty.com/2017/11/evans-bean-hampshire-grants/.

[48]Deposition of William Turnbull, October 4, 1820, Turnbull’s Pension File.

[49]Muster roll for 1st New York, Lt. Col. Van Dyck’s Company, for the Months of March April May & June 1780, Muster Rolls, Roll 66, Jacket 15. Entry for William Turnbull, Fernow, Documents Relating, 15:176.

[50]Certificate of Pension for William Turnbull, October 25, 1818, Turnbull’s Pension File.

[51]Deposition of Abraham Ten Eyck, January 14, 1820,ibid. For centuries, lieutenant colonels have been verbally referred to as “Colonel.”

[52]Deposition of John McLean, April 9, 1818,Pensions (S.42962 Roll 1694).

[53]Deposition of John McLean for William Turnbull, August 21, 1822, Turnbull’s Pension File. McLean had been able to sign his own name, but only made his mark on this deposition. For the above deposition from April 8, 1818, made for his own pension application, it looks like he signed it with a very infirm hand.

One thought on “William Dickens, John Rose, and William Turnbull: Soldiers of the 2nd New York Regiment”

Another great job Phil! As a former 1st Yorker, now a 2nd Yorker, this article was of great interest to me. As usual, well researched. Thanks and keep ’em coming!

Joe