When the American Revolution began, the Virginia Colony faced not one military-territorial contest, but four. Its ousted Royal governor, Lord Dunmore, was in the Chesapeake actively plotting a forcible return to power. A longstanding dispute with Pennsylvania over the headwaters of the Ohio had turned violent. A formal peace with the Shawnee on the northwest frontier was still pending after Col. Andrew Lewis’s October 1774 victory at Point Pleasant. A new war was brewing with the Cherokee to the southwest. Virginia’s early military preparations had to account for all of these threats.

In July 1775, Virginia created two full-time provincial regiments and a network of regional minute battalions to supplement the militia system. Seven more regiments were authorized in December. These regiments were intended for service in the east opposing the Crown and were taken into the Continental Army in 1776.

Largely forgotten are the colony’s independent provincial companies that were created at the same time to handle the western threats. They are often misidentified as militia and are glossed over in most histories, which reflects their short existence and the limited information in the surviving record. Just three of the companies are listed in E.M. Sanchez-Saavedra’s A Guide to Virginia Military Organizations in the American Revolution, 1774-1783. Another standard reference, Robert K. Wright’s The Continental Army, correctly notes that there were actually five original companies but provides little additional detail.[1]

This wafer-thin historiography validates a claim made by Charleston Physician Joseph Johnson in 1851. “Historians of the American Revolution all lived on or near the sea coast,” he lamented. “Many of the sturdy sons of the forest were therefore unknown to them, and the daring acts and patriotic sufferings of such worthy persons have never been written or published.” This is particularly true for provincial/state regulars, even though there were no Continental troops on the frontier until 1777. Its vast western claims placed the heaviest burden for western defense on Virginia’s shoulders. From 1775 to 1777, the creation of these independent provincial companies was the Old Dominion’s primary means of bearing this responsibility. Thereafter, Virginia fielded full battalions for frontier duty, most notably under George Rogers Clark, but still under the authority of its governor rather than Congress. Though little recognized, the early companies performed important service. Fortunately, there are more period sources to learn from than have previously been recognized.[2] The five companies were:

First West Augusta Company

One hundred enlisted men raised at Winchester, Frederick County.

Capt. John Neville

1st Lt. Andrew Waggener

Second West Augusta Company

One hundred enlisted men raised in the West Augusta District.

Capt. John Stephenson

Lt. Robert Beall

Lt. Edward Rice

Ens. Simon Morgan

Southwest Frontier Company

One hundred enlisted men, raised in Fincastle County.

Capt. William Russell

Lt. Joseph Crockett

Lt. James Knox

Lt. James Craig

Point Pleasant Company

One hundred enlisted men, raised in Botetourt County.

Capt. Matthew Arbuckle

1st Lt. Andrew Wallace

2nd Lt. Samuel Woods

3rd Lt. John Galloway (promoted)

Lt. James Thompson

Ens. John Galloway

Ens. Samuel Walker

Ens. James McNutt

Wheeling Company

Twenty-five enlisted men, raised in the West Augusta District.

Lt. Ebenezer Zane

The Old Dominion’s original charter claims stretched all the way to the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes. When the war began, Virginian settlers had established communities stretching from the Holston River valley (now mostly in Tennessee) to the western “district” of Augusta County (now primarily southwestern Pennsylvania) and the colony had every intention of asserting its claims. The dispute between Virginia and Pennsylvania had already come to blows. Pennsylvania had a history of using force to assert territorial claims, most notably against Connecticut in the Yankee-Pennamite Wars. Another threat to Virginia’s claims came with the Quebec Act of 1774, whereby Parliament annexed all of Virginia’s lands across the Ohio River to the Province of Quebec.[3]

The Ohio River was supremely important as the only navigable transportation artery into the west. It also served as a barrier between Virginia’s settlements and the western Indians. A so-called “proclamation line” drawn along the Allegheny Mountains had limited new settlement following the French & Indian War. Though meant to keep peace with the Indians, the line had been immediately controversial with Virginians who expected access to western lands after Britain’s victory. In 1768, the Iroquois agreed to cede trans-Appalachian lands south of the Ohio River to Virginia at the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. Though they claimed hegemony over the ceded territory, it was not really Iroquois land. The greatest impact fell on the Delaware and the Shawnee. Neither tribe lived south of the river, but the Shawnee had long viewed Kentucky as a proprietary hunting zone and militantly opposed Anglo-American settlement there.

This tension between the Indians and the Long Knives (as Virginians were known to the Shawnee) came to a head at the Battle of Point Pleasant on October 10, 1774. Lord Dunmore had organized an army in two divisions, personally leading one down the Ohio from Fort Pitt. The victory was won by the other division under Colonel Lewis, which approached north along the Great Kanawha River. An armistice was signed at Camp Charlotte pending more formal negotiations. In the meantime, Virginia militiamen remained at key locations along the Ohio River. At Point Pleasant, a rickety stockade and a garrison of one hundred men under Capt. William Russell protected wounded battle survivors and the important confluence of the Kanawha and the Ohio. They survived on half rations of leftover flour and the remnants of the army’s cattle herd, which now roamed free in the forest. In February, Shawnee chief Hokoleskwa (“Cornstalk”) arrived at the fort to return captives and horses as he had promised to do at Camp Charlotte.[4]

In one of his very last executive acts, Lord Dunmore stopped paying the garrisons at “Fort Dunmore” (Fort Pitt), “Fort Fincastle” at Wheeling, and “Fort Blair” (Russell’s stockade at Point Pleasant) and ordered the men to go home. Dunmore’s report to the House of Burgesses dated June 5, 1775 summarizes the state of affairs.

With respect to what Militia have been ordered on duty since the conclusion of the Indian expedition: it was thought requisite to continue a body of one hundred men at a temporary fort near the mouth of the Great Kenhawa, as well for taking care of the men who had been wounded in the action between Colonel Andrew Lewis’s division and the Indians as for securing that part of the back country from the attempts of straggling parties of Indians, who might not be apprised of the peace concluded, or other of the tribes which had not joined in it. It was likewise necessary to keep up a small body of men at Fort Dunmore, in like manner for the security of the country on that side, and also for guarding twelve Indian prisoners belonging to the Mingo tribe, which had not surrendered or acceded to the peace concluded only with the Shawanese; and seventy-five men were employed at this place for these purposes. Twenty-five men were likewise left at Fort Fincastle, as a post of communication between the two others; and all together for the purpose of forming a chain on the back of the settlers, to observe the Indians until we should have good reason to believe nothing more was apprehended from them; which, as soon as I received favourable accounts of, I ordered the several posts to be evacuated, and the men to be discharged.[5]

Thus, as revolution began, Dunmore fled the colony leaving the frontier undefended by authorized active-duty troops. The patriot Second Virginia Convention had renewed the colony’s militia law, but it had neither countermanded nor probably been aware of Dunmore’s order to dissolve the frontier garrisons. “I have,” wrote Captain Russell from Point Pleasant in June, “as long as in my power, procrastinated our departure from this Garison, expecting that ere now, we should Receive some Orders from the Convention, that might countermand the Governors Letter to me, but as none such have yet come to hand, I am this Morning preparing to start off.” Though ordered to leave, Russell decided on his own authority not to abandon the post completely. “The Garison we intend to let remain, as I think the distruction of it at this time might prove Injurious to the Country.”[6]

This was wise. Cornstalk warned Russell that the Piqua Band of Shawnee, the breakaway Mingo Band of Senecas, and the Cherokee were all preparing for war. The Mingoes were openly mocking Cornstalk’s Shawnee for seeking peace in defeat, calling them “big knife people.”[7]

There were also good reasons to question Dunmore’s motives for dismissing the garrisons. Three days after his report to the burgesses, the governor fled to the safety of the warship Fowey in the Chesapeake. John Connolly, a Loyalist and the governor’s civil and military representative at Fort Pitt, was soon suspected of treating with the Indians on behalf of the Crown rather than Virginia—with obvious implications. Connolly was in fact plotting to turn the western Indians against the rebellious colony. Virginia Patriots reasonably saw this counterrevolutionary stratagem as treachery. It would destroy a western peace that seventy-five Virginians had just died at Point Pleasant to achieve.

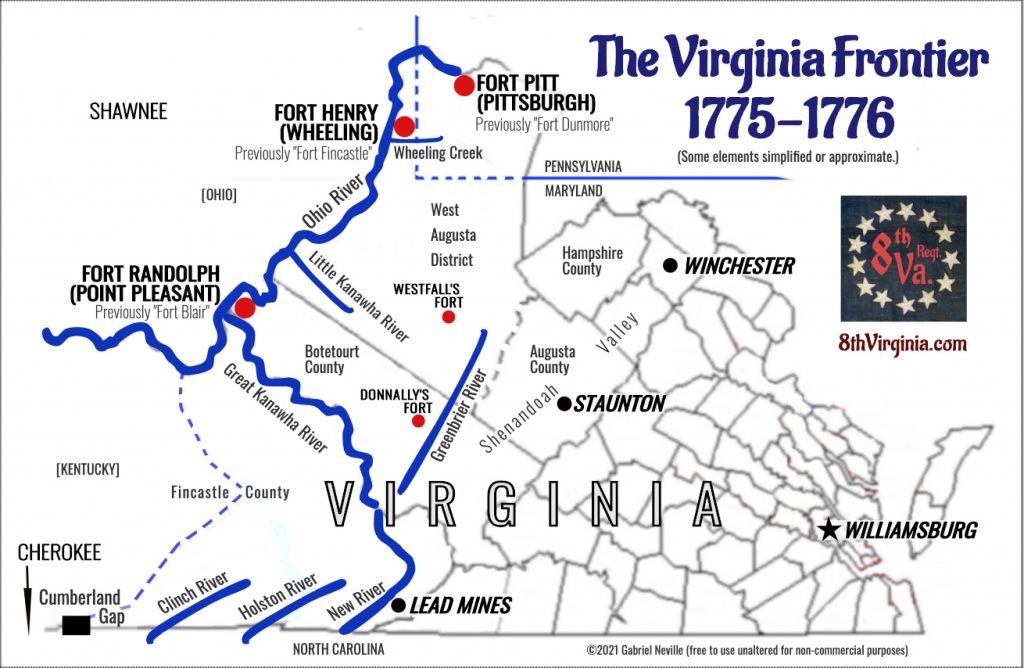

When the Third Virginia Convention convened at Richmond in July, it was clear that a restored military presence on the frontier was essential and urgent. The Convention approved a committee recommendation “that two Companies, of one hundred men each, besides Officers, ought, with all convenient speed, to be stationed at Pittsburgh; one other Company, of one hundred men, at Point Pleasant; twenty-five men at Fort Fincastle, at the mouth of Wheeling; and that one hundred men be stationed at proper posts in the County of Fincastle; for the protection of the inhabitants on the southwestern frontiers.” This was a significant step for a colony still edging its way into revolution. Where Dunmore had put short-term militia, the Convention now posted full-time Provincials with year-long enlistments.[8]

The hundred-man companies were to each have “one captain[,] three lieutenants, one ensign, four serjeants, two drummers, and two fifers.” The twenty-five-man company was to be led by a lieutenant. The ordinance also directed that all but the senior company be raised locally, that “the committees of the district of West Augusta, and of the counties of Botetourt and Fincastle, shall appoint the officers to the men in each to be raised,” and that “the commanding-officers to be stationed at Point Pleasant, and Fort Fincastle, shall be under the direction of, and subject to, such orders as they may from time to time receive from the commanding officer at Fort Pitt.”[9]

The First West Augusta Company

The last-mentioned commanding officer was Capt. John Neville. The Convention’s ordinance had stipulated that of the two Fort Pitt companies“the company ordered by this convention to garrison fort Pitt, under the command of captain John Neavill, shall be one.” He was a trusted and experienced figure who had served with Washington in the Braddock Expedition and with Dunmore in the recent expedition against the Shawnee. He was from the Shenandoah Valley town of Winchester but owned land in the West Augusta District and may already have taken up residence there. He had been elected in March as a delegate from the district to the Second Virginia Convention, but did not attend because he was ill. On May 16, he was elected to the West Augusta committee of safety.[10]

On August 7, 1775 the Third Convention resolved “that John Nevill be directed to march with his Company of one hundred Men and take possession of Fort Pitt and that the said Company be in the pay of the Colony from the time of their marching.” A number of independent companies of “gentleman volunteers” had formed that spring in Virginia. The Convention ordered these units dissolved when it authorized the first official provincial units. Though not certain, it appears that Neville had organized one of these volunteer companies and was asked by the Convention to convert it into the senior independent company. Veteran John Gerard specifically remembered that his status changed after their arrival at Fort Pitt. Three sources confirm that Neville’s men came from Winchester.[11]

Veteran Barney Karren recalled, “Our first march was to Fort Pitt . . . at the time of the expedition the Indians were in possession of this post, until our army arrived in the vicinity of the Fort where they evacuated the fort and in a few days we marched in & took possession.” The fort had been abandoned by the British in 1772 but reclaimed by Virginia and renamed “Fort Dunmore.” Despite Karren’s impression, it was actually Pennsylvanians who fled. Karren’s conflation is odd but explainable: he was apparently little more than a bystander and Indians may have been both present and more visibly threatening to the young soldier. Regardless, a more authoritative source is Pennsylvania official and future general Arthur St. Clair, who reported to Philadelphia on September 15, 1775, “We have . . . been surprised with a maneuver of the people of Virginia . . . About one hundred men marched here from Winchester, and took possession of the Fort on the 11th.” During his time at Fort Pitt, Karren recalled that they “made excursions in quest of Indians and to procure provisions.”[12]

By the time Karren’s enlistment expired, Neville had been elevated to major. Andrew Waggener, Neville’s lieutenant, was promoted to captain. “I was verbally discharged,” Karren remembered, “and my Captain told us that the British had landed at New York and that if I would again enlist we should march to the east in order to oppose the British Army.” He did reenlist and the company joined the new 12th Virginia Regiment, created under Virginia’s third (October 1776) authorization of forces. It was commanded by Col. James Wood (of Winchester) and by Neville, who became a lieutenant colonel.[13]

Neville and Waggener both served in the Continental Army for years and were taken prisoner at the surrender of Charleston in 1780. Neville was breveted a general at the end of the war and played a central role in opposing the Whiskey Rebellion at Pittsburgh in 1794. Karren quit after his second enlistment but joined the siege of Yorktown as a militiaman and escorted British prisoners to confinement on his way home.[14]

The Second West Augusta Company

There is no known source directly identifying the officers or men of the second West Augusta company. Unlike Neville’s company, this one was to be raised locally and existed only briefly before it was reassigned to a regiment almost a year before the Neville-Waggener company was. It can, however, be identified by deduction. In Virginia’s second (December 1775) authorization of forces, the Fourth Virginia Convention ordered the creation of seven regiments, requiring each county to provide either one or two companies. The Convention’s ordinance included a provision directing that “the officers of the one hundred men ordered from Fort Pitt, by a late resolution of this convention, shall be considered as part of the officers to be nominated by the committee of West Augusta, if the said officers shall incline to continue in the service of this colony.” Thus, just five months after its authorization and about three months after its formation, the company was reassigned.[15]

More can be discerned from a list of company officers in Virginia’s nine regiments that was compiled in the early months of 1776. Original company-level officers received their commissions only after they had met their recruiting quotas, at which time they were commissioned together. All of the commissions on the list are from 1776 with one exception: the first company of the 8th Virginia Regiment, a company from West Augusta. Given that West Augusta was authorized to count the company toward its enlistment obligation “if the said officers shall incline to continue in the service of this colony,” one can reasonably conclude that the officers shown on the 1776 list are (minus one lieutenant) the same men who led the company during its brief independent service. The company’s unique one-year enlistments also confirm that it was formed under the Convention’s 1775 rules.[16]

The captain of this company was John Stephenson, a half-brother of the better-known Col. William Crawford. Stephenson had acquired property in West Augusta in the late 1760s and hosted George Washington when the future president traveled to Pittsburgh in 1770. Stephenson was also a West Augusta militia captain who had been active in the contest with Pennsylvania and in the division commanded by Lord Dunmore in the previous year’s Indian war. While the company would originally have had three lieutenants, Stephenson’s subaltern officers in 1776 were 1st Lt. Robert Beall, 2nd Lt. Edward Rice, and Ens. Simon Morgan.[17]

The company was assigned to Col. Peter Muhlenberg’s 8th Virginia Regiment, joined Maj. Gen. Charles Lee’s southern campaign of 1776, and was present at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island. Epidemic malaria and Lee’s recall to the north interrupted a planned invasion of Tory-dominated East Florida. Stephenson’s company dissolved in September when its enlistments expired. Beall and Morgan both received promotions and were assigned to lead a company in the new 13th Virginia Regiment. James Wood later referred to Beall as “an officer of great merit.” Morgan was wounded at Eutaw Springs in 1781 but stayed in the army until the end of the war.[18]

Stephenson did not continue in Continental service, reportedly because of health issues (perhaps lingering malaria). Early in 1778, however, he participated in Gen. Edward Hand’s so-called “Squaw Campaign”into Ohio and again in Gen. Lachlan McIntosh’s expedition from Fort Pitt later the same year. Stephenson’s brother—William Crawford—was captured by Indians and brutally tortured to death in 1782. Washington corresponded with him to settle accounts with Crawford’s estate. Stephenson moved to Kentucky about 1790. He married, but had no children.[19]

Southwest Frontier Company

The colonel of Beall’s and Morgan’s 13th Regiment was William Russell, the former militia captain who had declined to dissolve the garrison at Point Pleasant. In the interim, Russell had returned home to Fincastle County where he was appointed captain of the independent provincial company for the southwest frontier. Though Russell was a graduate of William and Mary College, he was very much a frontiersman. He was a veteran of the French and Indian War. He lived on the Clinch River, which was then Virginia’s most remote settlement. In 1773 he led a train of settlers into Kentucky with Daniel Boone during which both men lost children in an Indian ambush. Russell commanded a company in Lord Dunmore’s War, was a justice of the peace, a member of the House of Burgesses, and a member of the Fincastle County committee of safety.[20]

Veteran David Gamble remembered that he “volunteered under Captain Russell, James Knox & Joseph Crocket . . . for the purpose of guarding the frontier.” James Wood remembered “the appointment of Joseph Crockett as a lieutenant in the fall of the year 1775. I was then a Member of the Convention.” Russell, supporting applications for Virginia bounty lands, certified “that James Knox, and James Craig, were officers in a regular company, raised by order of convention, for the protection of the southwestern frontier of this state, and continued officers according to their appointments in said regular company under my command, from September the 5th 75 till their appointments took place in the continental line.” Those appointments happened on February 24, 1776 when the Fincastle committee produced two companies for the colony’s new line regiments.Unlike John Stephenson’s company, which was reassigned by the Convention, Russell’s company remained in place. This reflected the still-looming threat from the Cherokee. Gamble recalled that he was posted at Ramsay’s Station near the “long island” of the Holston River, now Kingsport, Tennessee and “was discharged as soon as a Treaty was formed and a peace with the indians made.”[21]

Crockett’s company was assigned to the 7th Virginia Regiment. Gamble also joined this regiment, though in a different company. Their first engagement was at the Battle of Gwynn’s Island, which finally drove Dunmore from the Chesapeake. Colonel Crawford took command of this regiment in August. Knox’s company, meanwhile, served alongside Stephenson’s in the 8thVirginia. Knox and his junior officers were unable to meet their enlistment quotas and barely made it to Williamsburg in time to join the regiment in its southern venture.[22]

Crockett was a first cousin of the famed Davy Crockett’s father. After a promotion to major, he served again with Colonel Russell in the 5th Virginia. He returned to state service in 1779 as lieutenant colonel in command of a force known as Crockett’s Western Battalion. Gamble contracted malaria during his Chesapeake service, hired a substitute, moved back to Lancaster, Pennsylvania (his birthplace), joined the Pennsylvania service, was shot at Germantown, took six months to recover, and then developed a hernia while building a supply wagon. He never recovered from the “rupture,” using a truss to “remedy the evils arising from it” for the rest of his life.[23]

Knox and Craig saw their company all but wiped out by desertion and malaria during the southern expedition of 1776. Many of their men, still not technically Continentals, evidently objected to being taken out of Virginia. The duo was then selected in 1777 to lead a company in Daniel Morgan’s rifle battalion and saw important action during the Saratoga campaign. Knox was later appointed to command a western state battalion at the same time Crockett was. Crockett, Knox, and Craig all moved to Kentucky after the war.[24]

Russell became colonel of the 13th Virginia Regiment in December of 1776. He was then transferred to the 5th Virginia and was taken prisoner with most of the Virginia Line at Charleston in 1780. He died in 1793. His body was moved to Arlington National Cemetery in 1943.[25]

The Point Pleasant Company

While Stephenson and Knox were on their way to the Carolinas, Capt. Matthew Arbuckle’s company was making its way to Russell’s old post at Point Pleasant. Arbuckle had grown up on the frontier, been the first white man to explore the Great Kanawha all the way to the Ohio, and served as an officer and a scout in Dunmore’s War. William McKee attested later that Arbuckle “was appointed a Captain [by] the Committee of Bottetout County (of which Committee I was a member) in September 1775 agreeable to an Ordinance of Convention raising troops for the defence of the Western Frontiers for one year.” William Richmond recalled that “he entered the service by enlisting under Lieut. [Samuel] Woods in the County of Bottetourt, and State of Virginia for the term of one year in the month of Oct. 1775 and was marched from the County of Bottetourt to the Savannah Fort (now Lewisburg) and was stationed there for some time under Capt Mathew Arbuckle where the company Wintered and in the spring of 1776 he was marched to the fort at Point Pleasant on the Ohio River and was there stationed under the command of Col Nevil.” Jacob Persinger similarly recalled that the company officers were Captain Mathew Arbuckle . . . Andrew Wallace first lieutenant, [Samuel] Wood[s] 2d Lieutenant, John Galloway third lieutenant, and Samuel Walker Ensign.”[26]

Persinger recalled that they “marched to Fort Pitt . . . for the purpose of obtaining a supply of provisions, and thence to Point Pleasant.” This briefly-described travel likely meant retracing the path of Andrew Lewis’s 1774 trek up the New and Kanawha rivers to Point Pleasant and then more than two hundred miles up the Ohio to Fort Pitt before floating back downstream to take up their post. This may explain why it was not until May 16 that George Morgan, Congress’s Indian agent at Fort Pitt, reported that “Captain Arbuckle, with a company of Virginia Forces, departed from hence yesterday for the mouth of the Great Kenhawa where they are to rebuild the fort, and to remain till further orders from the Convention.” The new fort was called Fort Randolph after Virginia’s Peyton Randolph, the recently-deceased first president of the Continental Congress. Morgan also reported, “I thought it necessary to send an Indian with them, and a proper message on the occasion to the Delawares and Shawnees, accompanied by one of his officers, which I am sure will have a good effect.”[27]

Morgan also provided a report on his suspicions regarding a conference the Indians were having with the British at Fort Niagara.

Things are not right with the Northern Indians, particularly with the Senecas. I have now two Indians at Niagara, attending the treaty there . . . so that you cannot fail of receiving early intelligence of the designs of our enemies there, which I surmise, are against Pittsburgh. I have told Captain Nevil so, that he may be prepared.[28]

Persinger’s enlistment expired and he left the service on November 11, 1776. He said he “was in no engagement with the Enemy during this service.” Arbuckle, Wallace, and others, however, continued on.[29]

The Wheeling Company

A small twenty-five-man company served at the mouth of the Wheeling River. Originally called “Fort Fincastle” after one of Lord Dunmore’s titles, the post was renamed to honor Patrick Henry. Aside from its authorization, there is little information on this company’s experiences. Three sources identify Ebenezer Zane as the commanding lieutenant, with no elaboration. (Sanchez-Saavedra erroneously lists William McKee as commander. McKee’s actual contribution came the following year.) Zane is remembered for founding the settlement at Wheeling, for fending off Indian sieges in 1777 and 1782, and for being an ancestor of western novelist Zane Grey.[30]

The five independent Provincial companies authorized by Virginia in 1775 met an immediate need for securing the frontier from multiple threats. During their one-year service, Congress created the Continental Army and declared American independence. The threats to Virginia in the west remained, however, and 1776 would bring a new authorization of independent state companies.

[1]E.M. Sanchez-Saavedra, Guide to Virginia Military Organizations in the American Revolution, 1774-1783 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1978), 81; Robert K. Wright, The Continental Army (Washington: U.S. Army, 1986), 68. All known officers associated with a company are shown; they may not have served simultaneously. Relative rank of lieutenants is undetermined in some cases. The author is not related to John Neville.

[2]Joseph Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences Chiefly of the American Revolution in the South (Charleston: Walker & James, 1851), v.

[3]Philip S. Klein and Ari Hoogenboom, A History of Pennsylvania, 2nd ed. (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1980), 189-191.

[4]American Archives, Peter Force, ed., ser. 4 (Washington: Clarke & Force, 1833), 1: 1226.

[5]American Archives, ser. 4, 2: 1189-1190.

[6]Capt. William Russell to Col. William Fleming,” June 12, 1775, Reuben G. Thwaites and Louise Kellog, eds., The Revolution on the Upper Ohio, 1775-1777 (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1908), 12-17.

[8]American Archives, ser. 4, 3: 370.

[9]Ibid.; William Waller Hening, The Statutes at Large, Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature in the Year 1619, 13 vols. (Richmond, J. & G. Cochran, 1819-1823), 9: 9-14.

[10]Virginia Gazette(Dixon & Hunter), April 1, 1775; Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), July 6, 1775; William Jolliffe, Historical. Genealogical, and Biographical Account of the Jolliffe Family of Virginia, 1652-1893 (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1893), 74; Neville B. Craig, “Notices of the Settlement of the Country Along the Monongahela, Allegheny and Upper Ohio Rivers and Their Tributaries,” The Olden Time, 1 (1846): 446; “Augusta County (Virginia) Committee” in Edward G. Williams, “Fort Pitt and the Revolution on the Western Frontier,” Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, 59 (1976): 133. Because of an imperial moratorium on the formation of new counties, West Augusta was created as a “district” of Augusta County in 1774.

[11]W. J. Van Schreeven et al., eds., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1977) 3: 404; Virginia Gazette(Purdy), August 18, 1775. Purdy’s Gazette misidentifies Neville as “Joseph Neavill of Hampshire County” (John’s brother); Barney Karren pension S15906; John Gerard pension S42740; The Proceedings of the Convention of Delegates for the Counties and Corporations in the Colony of Virginia Held at Richmond Town, in the County of Henrico, on Monday the 17th of July 1775 (Richmond: Ritchie, Truehart & Du-Val, 1816), 3, 5. All pensions applications accessed at Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters, revwarapps.org.

[12]Karren pension; “Arthur St. Clair to Governor Penn,” September 15, 1775, William Henry Smith, ed., The St. Clair Papers, 2 vols. (Cincinnati: R. Clarke, 1882), 1: 361; Brady J. Crytzer, Fort Pitt: A Frontier History (Charleston: History Press, 2012), 123-124; Williams, “Fort Pitt,” 59: 140.

[13]Karren pension; Sanchez-Saavedra, Guide, 67. Neville is misidentified as “James Neville” by Sanchez-Saavedra here.

[14]Sanchez-Saavedra, Guide, 42, 57; Karren pension.

[16]“A List of Captains and Subaltern Officers in the Virginia Service,” C. Leon Harris, transc., revwarapps.com; William Owens pension S4640. Col. Peter Muhlenberg reported to General Washington in February, “There is at present one entire Company wanting in my Regiment in the room of Captn Stinson’s from Pittsburg, whose Time of Enlistment expird in September last.” Stephenson’s name is often written “Stinson,” evidently reflected the way it was pronounced Peter Muhlenberg to George Washington, February 23, 1777, Founders Online, National Archives).

[17]William Crawford to Washington, January 7, 1769, Washington-Crawford Letters, 11; Washington Diary, October 16, 1770, Founders Online; Glenn F. Williams, Dunmore’s War (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2017), 34, 40, 41, 83-84; Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register of the officers of the Continental Army during the war of the revolution (Washington, DC: Rare Book Shop Publishing, 1914), 94, 401-402, 464; Franklin Ellis, History of Fayette County (Philadelphia: L.H. Everts, 1882), 785.

[18]Calendar of Virginia State Papers, 3:121; Journals of the Council of State, 1: 227; William Bailey pension W5778; Robert Beall bounty land warrant BLWt431-300; all bounty land warrants with BLW numbers accessed at Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters, revwarapps.org.

[19]Washington to John Stephenson, February 13, 1784, Founders Online. See also Gerard pension.

[20]Virginia Gazette(Rind), December 23, 1773; Richard Barksdale Harwell, ed., The Committees of Safety of Westmoreland and Fincastle (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1956), 17-18, 61, 67; Williams, Dunmore’s War, 2-4; Jim Glanville, “The Fincastle Resolutions,” The Smithfield Review, 14 (2010): 86.

[21]David Gamble pension S32264; Joseph Crockett and James Knox bounty land warrant files, Library of Virginia; Harwell, Committees of Safety, 82-83. In a separate statement in the file Joseph Crockett wrote, “I do certify that James Knox was appointed an officer to a Company to guard the frontier of Virginia without limitation in September 1775 and continued in Service til February following. He was then appointed a Captain in the 8th Virginia Continental line.” Gamble’s dates do not align with the record and may refer to prior militia service under the same officers.

[22]Gamble pension; “Rank of officers in Col. Abraham Bowman’s regiment as settled by the Board of officers appointed by the Hon Brig. Gen. Scott,” Clark Family Papers, Filson Historical Society, mss. A C592c; Sanchez-Saavedra, Guide, 52.

[23]Gamble pension; Sanchez-Saavedra, Guide, 45-47, 133-134. Joseph Crockett’s father William and Davy Crockett’s grandfather David were brothers.

[24]Thomas Jefferson, “Notes on Threatened British Invasion,” December 1779, Founders Online; Kellogg, Frontier Advance, 402-403.

[25]Elizabeth Yarrington Russell, “William Russell of Virginia: Revolutionary Soldier and Statesman Reburied in Arlington Cemetery,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 52 (1944): 267-272.

[26]William Richmond pension S9088; Jacob Persinger pension S30019. A different version of the officers’ names appears in John Jones pension W7920.

[27]Persinger pension; “George Morgan to Lewis Morgan,” May 16, 1776, America Archives, 6: 475.

[29]Persinger pension; Andrew Wallace bounty land warrant BLWt543-300; Heitman, Register, 566.

[30]John Greene pension W4216; James Johnson pension S36636; National Archives, Compiled Services Records … Revolutionary War, 1077: 1224-1225.

5 Comments

John Neville was a friend of Daniel Morgan. Presley Neville, John’s son, married Nancy Morgan, Daniel Morgan’s eldest daughter. During the Whiskey Rebellion Presley Neville and his family, including John was threatened by the rebels and that did not set well with Daniel Morgan.

I wonder if you intentionally did not mention at least one other independent frontier company, that of Henry Heth’s Independent Company garrisoned at Ft Pitt from 1777 until 1781 he was made supernumerary

Thank you for this. It may be that a third article in this series is warranted. Sanchez-Saavedra lists five independent companies raised in 1777, including the company lead by Heth. I have not researched these closely but have thought them to be Continental, not State units. If they were, their status would be more akin to that of Hugh Stephenson’s and Daniel Morgan’s 1775 companies that went to Boston. As noted in part two of this essay, though, the distinction wasn’t always even clear at the time. Note that in John Gibson’s attestation supporting Heth’s (state) bounty land claims he said Heth “enterd into the service of this State on Continental establishment in March 1777 and Continued therein ‘til January 1781.” I conceived of these articles as an examination of State independent companies, but a third installment seems like a great idea if enough material can be found.

Captain David Looney had a company of men who are not mentioned here. Daniel Boone served as a Lt. under him in Fincastle County Virginia. He was later promoted to Lt Colonel.

Is there a list of the men who were part of Second West Augusta Company?