During the Revolutionary War, Pittsburgh was a place of constant political and economic intrigue, double-dealing, subversion, back-stabbing, disloyalty, and treachery. One of the earliest and most jaw-droppingly ambitious plans to secure the city for the British came from the mind of Dr. John Connolly.[1] Word of his “plot” spread widely across the colonies in 1775 and came to symbolize the lengths to which Loyalists were willing to go to foil the American Revolution.

The doctor was born in Pennsylvania and had an eye for adventure, but his parents insisted on a medical education. Still, he managed to join the army on campaigns in the Caribbean and frontier. In Connolly’s telling, the experience “taught me to endure hardships, and gave me agility of body, and an aptitude to enterprize, very proper to form a partisan officer.”[2] Armed with an inheritance after his mother died, the title doctor, and experience on the frontier, Connolly settled in Pittsburgh.[3]

The road to wealth, status, and power lay through land acquisition and the Virginians were the most aggressive about it in the Ohio River valley. Predictably, Connolly’s ambition brought him into frequent contact with many of Virginia’s leaders, including George Washington and the governor, Lord Dunmore. He became one of the governor’s agents in asserting Virginia’s sovereignty claims in the west. In the dispute between Virginia and Pennsylvania that followed, the two colonies took turns arresting one another’s officials. Arthur St. Clair, future Continental major general, arrested Connolly. Paroled, the doctor organized local Virginians into a de facto armed militia that took control of the town. It earned Connolly the animus of Pennsylvanians. At the close of Dunmore’s War between Virginia and the Shawnee and Mingo Indian polities, Connolly received command of seventy-five men at Fort Dunmore (Fort Pitt) and charge of the Indian leaders held hostage pending the return of white captives.[4]

As agents and colonial representatives on the frontier tried to implement the treaty ending Dunmore’s War, the Revolution’s opening brought things to a head. When word of the fighting at Lexington and Concord arrived at Pittsburgh in May, a local committee expressed support for New England. Connolly resolved to remain loyal to England. He had already hitched his fortunes to Lord Dunmore.

The doctor moved more quickly than the rebels. He bombarded his Indian hostages with speeches predicting the king’s success. Then he met with several Indian leaders in Pittsburgh in June, where he asserted that he extracted promises from them to support the king.[5] In truth, the Native American leaders with whom Connolly met did not fully understand the brewing conflict between Great Britain and its colonies or the speed with which Connolly’s influence in the area was dissipating. Aware of Connolly’s efforts, Whigs had launched their own diplomatic initiative among the Indians north of the Ohio River.

While he harangued the Indians, Connolly also tried to gather Loyalists in the area around him. Drawing the attention of the local Committee of Safety, St. Clair ordered him arrested again, perhaps a small bit of payback for Connolly’s decision to ignore his earlier parole from arrest by Westmoreland County. (St. Clair may have entrapped him by having a fake messenger wake Connolly in the middle of the night with fake instructions from Dunmore, only to arrest Connolly when he opened the packet.) Bound for Philadelphia as a prisoner, Connolly wrangled an escape by relying on some allies, returned to Pittsburgh, and then set out for Virginia’s coast with a supporter, William Cowley, claiming he was headed east to report on the progress in wrapping up the loose ends of Dunmore’s War. He finally met with the governor on August 9.[6]

Connolly had already concocted a plan for supporting the crown.[7] He believed, erroneously, that he had formed a confederation of western Indian nations that would cooperate with western Loyalists to restore British control over Virginia; Loyalists and Indians would strike from the frontier while a reinforced Dunmore would operate from the coasts.[8] The plan evolved, but Connolly would have to return to the frontier and the Indian allies he believed he had secured. He planned to travel by way of Quebec. Dunmore sent Connolly to Boston to carry dispatches, meet with British commander Gen. Thomas Gage, and seek approval. The doctor left on August 22.

In Boston, he laid a more comprehensive proposal before the general. It had several elements. He asserted the Ohio Indians were prepared to “act in concert” against Britain’s enemies. Connolly assumed that a substantial force of Loyalists remained around Pittsburgh and would serve under him in exchange for having their land titles confirmed in the conflict with Pennsylvania. General Gage would make Connolly a major and order Capt. Hugh Lord, then garrisoning several posts in the Illinois Country, to march to Detroit and place himself under Connolly’s command. Connolly would then lead a campaign to seize Pittsburgh, Cumberland Maryland, and then follow the Potomac down to Alexandria, Virginia, where he would rendezvous with Lord Dunmore campaigning from the tidewater region. Should they fail at Pittsburgh, Connolly’s scratch army would retreat down the Ohio to the Mississippi and venture into East Florida before taking ship back to Norfolk. An artillery officer would accompany Connolly to Detroit and help collect artillery to reduce Fort Dunmore/Pitt and Fort Fincastle/Henry. Connolly would be authorized to make presents to the Indians to encourage their participation. Finally, Gage would provide those arms necessary to carry the plan into fruition.

Gage approved. Connolly had to get to Detroit, but the American invasion of Canada precluded traveling via the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes. Instead, he would have to return to Dunmore and find an alternative route. He finally departed Boston on September 20 with William Cowley still in tow. A day out from the port Connolly filled Cowley in on his plans and asked him to join him. Connolly planned to take a small vessel from Portsmouth down to St. Augustine, obtain guides to travel through Cherokee territory, and then up to the Shawnee and Delaware nations in Ohio, where he would hand out Royal commissions, before traveling on to Detroit and rendezvousing with Captain Lord.[9] Cowley, who had been through much with Connolly, recorded the details in a draft letter to Washington. When their ship put into Newport, Rhode Island, on September 30, Cowley attempted to smuggle the letter out. Failing, he left all of his belongings aboard and snuck off the ship, eventually finding a way to post the letter to Washington. Connolly’s “plot” was thus discovered.

Connolly arrived in Portsmouth, Virginia, on October 12, received a lieutenant colonel’s commission from Dunmore, and opted to make a speedier journey to Pittsburgh through Maryland, realizing that the roundabout route through St. Augustine would take too long. He set off on November 13 with Lt. Allen Cameron and Dr. John Smyth. Cameron was a Scots-born South Carolinian who had hoped to join the British war effort in Boston, but Dunmore decided to send him with Connolly. Smyth was a Marylander, already well known there as a committed, and obnoxious Loyalist. He was bound for West Florida, where he might escape the war, but Dunmore and Connolly prevailed upon him to return to Maryland.

The party, plus Connolly’s enslaved servant, traveled by boat into the Potomac, but finally went ashore due to adverse winds and traveled overland. As they passed through Frederick, Maryland, the local militia were holding a muster. Connolly was recognized, but the group kept moving, eventually stopping at a public house beyond Hagerstown on November 19. Connolly knew the landlord and had the misfortune of encountering a private who had served under him—who now took the opportunity to salute him and draw attention. Smyth proposed splitting up, but Connolly let it pass. The private went to a tavern in Hagerstown, where Connolly had also been noticed earlier in the evening. Chit chat among the patrons led the private to confirm Connolly’s location nearby to some local patriots. They promptly reported the news to a local militia colonel, into whose hands had fallen a letter Connolly composed to John Gibson in August at Dunmore’s direction.[10] Connolly’s letter to Gibson did not reveal his plans, but confirmed his loyalist sympathies. Worse, it was enclosed with a letter from Dunmore to the Ohio Indians, encouraging them to side with the crown in the escalating conflict. (Connolly mistakenly thought Gibson a Loyalist; in fact, he was a Whig.) The Hagerstown colonel dispatched a party to the common house in which Connolly and his party were staying. Smyth remembered a party of thirty-five rough men, mostly German, “who rushing suddenly into our room, with their rifles cocked and presented close to our heads while in bed, obliged us to surrender.”[11]

The local committee, which Dr. Smyth described as “ignorant, rude, abusive, and illiberal,” held a quick hearing and then decided to send Connolly’s group back to Frederick, where a larger committee could consider their case. It was a challenging journey as the same men who had seized them served as a guard. According to Smyth, “this party consisting solely of rude unfeeling German ruffians, fit for assassinations, murders, and death, treated us with great ignominy and insult; and without the least provocation abused us perpetually and with every opprobrious epithet language can afford.”[12] There, he encountered another colonel just in from Boston. That officer was aware of Connolly’s plans from General Washington, who had received and forwarded the news from Cowley to the Continental Congress on October 12.[13] The Frederick Committee interviewed Connolly on November 23.[14] A thorough search of Connolly’s baggage turned up further evidence of his plans, and his arrest became final. The jig was up and his “plot” was foiled.

Word spread widely and newspapers reprinted accurate descriptions of Connolly’s plan dated November 26, just a week after his initial capture in Hagerstown.[15] Congress received the news on December 1.[16] On December 5, a young English adventurer trapped in the colonies when the war broke out visited Connolly during his Frederick confinement and found him nevertheless in good spirits, but the Englishman, Nicholas Cresswell, was not allowed to meet with him alone.[17] (Cresswell himself was under suspicion, having traveled into Kentucky earlier that year and frequently espoused his disgust at American pretensions of liberty.) While confined in Frederick, Connolly helped Dr. Smyth escape with some important paperwork, including personal letters, but the doctor was recaptured on January 12. In the interim, documents from his Frederick interview were printed on December 22 and appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette on December 27. Two days later, Connolly and Cameron set out under guard for Philadelphia, where they were imprisoned.

Connolly remained in various stages of confinement as the war progressed, but was finally made eligible for parole and exchange on July 4, 1780. He traveled to New York on parole, becoming Gen. Sir Henry Clinton’s problem. He was finally exchanged on October 25 and promptly began proposing various schemes for waging war on the frontier and capturing Pittsburgh. He was accepted into the army and assigned to Maj. Gen. Charles Cornwallis, who gave him command of Virginia and North Carolina Loyalists. But Connolly was ill and sought a leave of absence in the fall of 1781. It being granted, he left Yorktown on September 21, 1781 to go “on vacation” among friends in Virginia. He wandered into American lines and was promptly captured and imprisoned again until March 1782. Thus, the doctor whose imprisonment for plotting against the United States began in 1775 found himself in prison again when Cornwallis surrendered.[18] After the war, Connolly made his way to England to seek compensation for his losses during the war, but eventually returned to America, living in Detroit. Connolly sought to recover his fortunes and status on the frontier. But, his day had passed and the doctor who had plotted to capture Pittsburgh eventually moved to Montreal, where he died in 1813.[19]

[1]William Cowley to George Washington, September 30 – October 12, 1775, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0063.

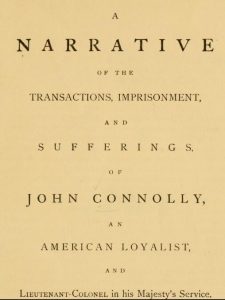

[2]John Connolly, A Narrative of the Transactions, Imprisonment, and Sufferings of John Connolly, an American Loyalist and Lieutenant-Colonel in his Majesty’s Service in which are Shewn the Unjustifiable Proceedings of Congress, in his Treatment and Detention (London: 1783), 3.

[3]Clarence Monroe Burton, John Connolly: A Tory of the Revolution (Worcester, MA: The Davis Press, 1909) 3; Connolly, Narrative, 2.

[4]“Affairs at Fort Pitt,” Reuben Gold Thwaites and Louise Phelps Kellogg, eds., The Revolution on the Upper Ohio, 1775-1777, Draper Series, Volume II (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1908), 17-18. The Virginians referred to Fort Pitt as Fort Dunmore for a brief period.

[5]Ibid., 19-20; Hermann Wellenreuther and Carola Wessel, eds., The Moravian Mission Diaries of David Zeisberger, 1772-1781 (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005), 260; Connolly, Narrative, 12-13.

[6]Burton, John Connolly, 17-18; Cowley to Washington, September 30 – October 12, 1775; Valentine Crawford to Washington, June 24, 1775, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0014.

[7]Connolly, Narrative, 13-14; J.F.D. Smyth, A Tour in the United States of America, Vol II (London: G. Robinson 1784), 246-248.

[8]Connolly, Narrative, 28-29.

[9]William Cowley to George Washington, September 30 – October 12, 1775.

[11]Smyth, A Tour of the United States of America, 2: 252.

[13]Washington to John Hancock, October 12, 1775, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0140-0001.

[14]Samuel Chase to John Adams, November 25, 1775, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-03-02-0171.

[15]“Connolly’s Plot,” Thwaites and Kellogg, The Revolution on the Upper Ohio, 136-142.

[16]Hancock to Washington, December 2, 1775, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0426.

[17]Nicholas Cresswell, The Journal of Nicholas Cresswell(Norwood, MA: Dial Press, 1924), December 5, 1775.

[18]Burton, John Connolly, 28.

[19]Ibid., 38. Connolly was likely trying to separate Kentucky from the United States. His old Pennsylvania nemesis, Arthur St. Clair, was at that time Governor of the Northwest Territory. Hearing that Connolly was in Kentucky, he alerted local authorities to the doctor’s history and ordered his subordinates to keep an eye on the man. Arthur St. Clair to John Jay, December 13-15, 1788, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jay/01-05-02-0061.

3 Comments

Well done! Connolly was a real weasel.

Interesting article on a little-known aspect of the Revolution! The number of fantastic schemes that characterized the outbreak of the war is incredible. I found it amusing that Loyalists seemed to like Patriot Germans almost as little as Patriots liked Hessians. Nicely done!

Thanks gents. Neither Smyth or Connolly had a kind word to say about the Germans they found moving in around Frederick, MD or southwestern PA. Fellow Englishman Nicholas Cresswell was rather unkind as well. Honestly, I never realized there were so many German immigrants in that area before the war.