“What say you now, Sir Peter Parker!”[1]

The high and mighty will sometimes do seemingly odd things in order to make a point. Like, for instance, having oneself rowed into a channel in front of Fort Moultrie to see if the water’s depth was sufficient to accommodate an attacking ship. The date was May 27, 1780, and after four years Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island was finally in British hands.[2]

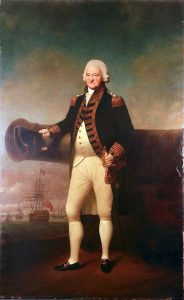

Lt. Gen. Sir Henry Clinton was among the high and mighty. Born about 1730 in Newfoundland, he was the only son of George Clinton, an admiral in the Royal Navy who served as governor of colonial Newfoundland in 1731 and governor of New York from 1743 to 1753. Little is known of Henry’s early life. His wife Harriet bore him five children in five years of marriage until her death in 1772, a loss that left him emotionally devastated. He was an able soldier but known to be prickly and quarrelsome, often aloof, insensitive, and at times petulant. After studying his voluminous writings and consulting with his biographer, a psychologist inferred that Clinton, who once referred to himself as a “shy bitch,” was compulsive, neurotic, blame-shifting, self-defeating, and guilt-ridden. In reality he was a paradox; he resented authority while under it, was greedy for it, yet he was uncomfortable when wielding it. During his career he proved himself to be a troublesome subordinate, a trying colleague, and a vexing superior.[3]

Clinton became a provincial army officer in New York in 1745 and a regular British army officer in 1751. Because of his distinguished service in Germany during the Seven Years’ War he ascended through the ranks of the officer corps so that by the time he landed in Boston in 1775 he had attained the rank of major general. He exhibited coolness and initiative under fire at Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. A year later, however, he played little more than a spectator’s role in South Carolina while he and his army command watched a Royal Navy squadron of warships fail to reduce a small unfinished fort constructed of palmetto logs and sand on Sullivan’s Island at the entrance of Charleston harbor on June 28, 1776.[4]

Commanding the Royal Navy at Sullivan’s Island on June 28, 1776, was Cde. Sir Peter Parker. His father was Rear Admiral Christopher Parker and consequently Peter, born in 1823, was practically raised in the Royal Navy. He began his sea service at a young age and by 1743 had advanced to the rank of lieutenant. A series of promotions rewarded his ability which was particularly on display during the Seven Years’ War after which he retired in 1763 at the rank of captain. He received the honor of knighthood in 1772, returned to active service in 1773, and was elevated to the rank of commodore in 1775. Parker sailed across the Atlantic aboard his flagship Bristol, at the head of a squadron that transported troops to the North American theater from Cork, Ireland.[5]

Parker was nearly a decade older than his joint commander Henry Clinton and seems to have been Clinton’s personality polar opposite. Perhaps not the most brilliant officer in the Royal Navy, Parker nevertheless had broad experience with independent command. He was usually polite and affable, occasionally stubborn, but confidant and certainly long-suffering with Clinton. And he was generally a good tactician.[6]

Clinton and Parker had come to South Carolina as a consequence of an ill-conceived British strategy designed to restore royal government in the southern colonies. North Carolina had been the campaign’s primary objective but circumstances shifted attention to Charleston, the region’s center of commerce and a favored discretionary target. If the British could seize an uncompleted fort on Sullivan’s Island, they could control Charleston harbor, capture the city, and establish a base for future operations inland. A victory here could bring the war to a speedier conclusion, at least in theory. Practically speaking, the fort on Sullivan’s Island was an attainable prize, but Clinton and Parker had not the manpower, artillery, or time necessary to capture and hold Charleston. And if they did succeed, any loyalists who flocked to the king’s standard would be abandoned to face the fury of the rebels when British regulars returned north from whence they came.[7]

Parker settled his fleet in Five Fathom Hole, a broad anchorage off Morris Island at the southern entrance of Charleston harbor. He and Clinton worked to come up with a viable plan that would accomplish their mission. Instead, through a series of communications delivered in writing or verbally through intermediaries that fostered general misunderstanding between the co-commanders, they formulated an incoherent strategy that was doomed to tactical failure. They originally envisioned a reduction of the fort on Sullivan’s Island by way of a sudden and rapid stroke consisting of a amphibious assault on the north end of Sullivan’s Island that would be launched simultaneously with a naval bombardment of the fort—a coup de main. But when Clinton reconnoitered the islands in a small sloop he was disappointed to find that the violent surf that pounded the shore of Sullivan’s Island, combined with an entrenched patriot force ashore, made a landing there too hazardous. Alternatively, Long Island would be considerably easier to occupy and he decided that cooperation with the movements of the fleet against Sullivan’s Island could be best managed if the army established a base there. This decision would prove fatal.[8]

The Battle of Sullivan’s Island on June 28, 1776, could have and probably should have been a decisive British victory. Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, who was the most experienced officer on the Continental side, considered Col. William Moultrie’s position on the island a veritable slaughter pen that would not hold against the British for half an hour. Lee predicted that the garrison would be inevitably and needlessly sacrificed and it was beyond his comprehension just why the island had been occupied and fortified in the first place. To prevent such a calamity he ordered the construction of a narrow pontoon bridge, a rickety affair not completed by the time of the battle, which extended precariously from Sullivan’s Island to the mainland. Lee was not alone in his opinion of the island’s indefensibility but Moultrie, who had the support of South Carolina’s chief executive, President John Rutledge, would not be persuaded to abandon the post. He and his inexperienced but brave and determined men, about 435 in all, would hold their fort come what may, a shortage of gunpowder notwithstanding.[9]

Covering Moultrie’s rear at the northeast end of Sullivan’s Island—a fortified position known as the Advance Guard—was his old friend Lt. Col. William “Danger” Thomson. Thomson led 780 North Carolina and South Carolina troops who were determined to thwart any attempt by Clinton’s 3,000 or so British soldiers encamped on Long Island should they try to cross the channel that separated the two islands and attack the fort from behind.

The channel that separated Long Island (now Isle of Palms) from Sullivan’s Island, known as Breach Inlet, would be forever linked with the name of Henry Clinton after the battle. He would not be ashore very long before he discovered to his horror—“unspeakable mortification” were his words—that reports of the channel between Long Island and Sullivan’s Island being passable on foot at low tide were absolutely false. Breach Inlet, said to be only eighteen inches deep at low tide, was in fact seven feet deep. Clinton had only fifteen lightly-armed flatboats, enough to put 600 or 700 men across the inlet at a time. Across the inlet, Thomson’s North and South Carolinians with their breastworks and cannon rendered a landing on Sullivan’s Island impossible without great sacrifice.[10]

Having been “enticed by delusive information,” Clinton notified Parker that he could not attack across Breach Inlet as planned; the army could offer no more than a diversion in concert with Parker’s naval attack on the fort. As an alternative, Clinton proposed to transport troops from Long Island by boat and land near Haddrell’s Point to attack the rebel battery and capture Mount Pleasant. This scheme depended on the support of the Royal Navy and Parker agreed in principle to send frigates flank the rebel position. This plan, however, was never positively developed.[11]

After a week or so of weather delays, on the morning of June 28, 1776, nine ships from Parker’s squadron loosened their sails, cruised from their anchorage in Five Fathom Hole off Morris Island, and dropped anchors in two parallel battle lines abreast of the fort and approximately 400 yards off Sullivan’s Island. Parker’s signal from the Bristol unleashed a furious cannonade that lasted nearly ten hours. Joining the Bristol in the center of the first line of ships was the 50-gun Experiment, and on the flanks were the 28-gun frigates Active and Solebay. The 20-gun corvette Sphynx accompanied by the 28-gun frigates Acteon and Syren formed a second parallel line behind the first, filling the intervals between the ships of the first line. The bomb-ketch Thunder with 8 guns that included a large mortar, protected by the armed transport Friendship’s 22 guns, was anchored to the east and behind the line about a mile and a half from the fort.[12]

The South Carolinians in the fort replied slowly and methodically, taking careful aim with their cannons to conserve their powder. Aside from what amounted to demonstrations on Long Island, Clinton watched impotently. At one point, from Parker’s perspective, it appeared that his gunners were having success but this proved to be an illusion. Back in Charleston the townspeople crowded the wharves and waited in prayerful but dreadful anticipation for news of the battle’s outcome. As darkness fell on Charleston, the view of the battle took on the appearance of a heavy thunderstorm with its repeated flashes of lightning and peals of thunder.

To Charleston’s relief, a dispatch boat sent by Moultrie finally appeared through the darkness bringing news that the British ships had retired and that the South Carolinians were victorious. More than victorious, actually. The brave but outnumbered, outgunned, and undersupplied Americans had decimated their British foes. Despite the long hours of bombardment, only twelve men inside the fort were killed. Twenty-five were wounded, five so grievously that they subsequently died of their injuries, raising the fort’s final death toll to seventeen. By Parker’s count the British suffered 205 sailors and marines killed and wounded. He was among the wounded and the Bristol was so riddled that her seaworthiness was questionable. The loss of men and damage to the ships rendered a renewal of the attack on the next morning unfeasible. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island was America’s first absolute victory.[13]

Undoubtedly the construction of the fort was an important factor in the Americans’ success. Clinton would write that “the Materials with which Fort Sullivan is constructed form no inconsiderable part of its strength. The Piemento Tree, of a spungy substance, is used in framing the Parapet & the interstices fill’d with sand. We have found by experience that this construction will resist the heaviest Fire.” Maj. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney observed on the day after the battle that “the Fort, though well peppered with shot, has received scarcely any damage, not a single breach being made in it, nor did the Palmetto logs, of which it is built, at all splinter.”[14]

The fortunate use of the Sabal palmetto, commonly known as the Cabbage Palmetto, in no way diminishes the determination of the men inside the fort and stationed at the Advance Guard. The American strategy had been relatively simple: hold two perilous positions on an island against overwhelming odds, while lacking a secure escape route. And without adequate munitions, inflict as much damage on the enemy as possible. In this they were surprisingly successful. Had the fort been breached by naval gunfire or had the British crossed Breach Inlet the Americans on the island would have been trapped. But the South Carolinians did not operate in a vacuum. The British tactical plan was confused, poorly communicated, flawed at its core, and herein germinated the seeds of British failure and American success.

Setting aside American valor and the palmetto tree, the British defeat can be distilled down to two main factors, British mistakes that initiated a cascade of consequences of their own. First chronologically but arguably of secondary importance was the landing and continued presence of General Clinton and his British army troops on Long Island after it was discovered that the depth of Breach Inlet at low water rendered the British army tactically impotent. Clinton being on Long Island also adversely affected the two commanders’ ability to devise a plan. They never communicated very well in the first place, causing Parker to later remark to Clinton that “in Our private Conversations, we have often misunderstood Each Other.” With Clinton ashore on Long Island their ability to communicate, either by written word or through intermediaries, completely broke down.[15]

Clinton’s alternative proposals aside, Parker considered the reduction of Fort Sullivan to be a primarily a naval operation. Once a naval bombardment silenced the batteries in the fort, Parker planned to land seamen and marines under the guns to storm the embrasures. A union flag would be hoisted at the fort as a signal for Clinton to bring over troops to help the sailors and marines retain possession of the fort in case of a counterattack. That Clinton’s force was in no position to assist beyond creating a diversion at Breach Inlet would be a matter of long discussion afterwards, but for now, Parker meant to continue the Royal Navy’s long record of success against land fortifications.[16]

The second main contributory factor to the British defeat was the closing distance between the two opponents, a factor over which the Americans in the fort had no control but from which they certainly benefited. Combatants and eyewitnesses representing both sides generally and consistently agreed that the distance from which the ships engaged the fort was roughly 350 to 500 yards. The most notable outlier was Henry Clinton who placed the ships about 900 yards offshore. Parker estimated “450 yards or less,” while Generals Moultrie and Lee and Capt. Barnard Elliott, inside the fort, estimated 400 yards. Bristol’s master Capt. John Morris gauged the distance to be “two Cables in 7 fm [fathoms] Water” which is congruent with the estimates of Parker, Moultrie, and Elliott.[17]

Even though Clinton badly overestimated the distance between ships and fort, he considered Parker’s failure to get close to the fort to be the foremost factor in the British defeat. In his opinion, his and Parker’s joint efforts would have been successful only “if the Ships should bring up as near the Fort as the pilots assured Sir Peter Parker in my hearing Presence was possible (about 70 yards) [emphasis added]; as the fire from the Ships Tops being so much above the Enemys Works would probably at that distance soon drive raw Troops (such as those assembled there were certainly at that time) from their guns, and it was not unlikely that our moving into their rear at that critical Moment might cause them suddenly to evacuate the Island.” In a July 8 letter to colonial secretary Lord George Germain he expressed his disappointment that when the fleet attacked the fort, “they did not appear to be within such a distance, as to avail themselves of the fire from their tops, grape Shot, or Musquetry.” For this reason he was most apprehensive “no impression would be made upon the Battery.”[18]

Col. Christopher Gadsden, who viewed the battle from Fort Johnson across the harbor on James Island, later forwarded information gleaned from five deserters from the British fleet, two men from the Bristol and three from the Acteon, who were all former American seamen who had been impressed into His Majesty’s service when their ships were stopped at sea. The sailors reported that one of the first shots from the fort aimed at the Bristol killed a man in the rigging, causing Parker to order all of his men out of the tops and depriving the British of a vantage point from which to attempt to pick off Americans in the fort. They said that in the unlikely event of a second British attempt to take the palmetto fort, Parker would surely bring his ships as close as possible in order to rake the fort with musketry from the ships’ tops.[19]

Parker himself agreed with the premise that the ships had been too distant from the fort but he tried to absolve himself of responsibility by arguing that it was his harbor pilots who refused to move in closer. He offered for an excuse that as the Bristol approached the fort a cannonball grazed his left knee, sending him aft to have it examined. When he returned to the forepart of the quarterdeck he was astonished to discover that the ship had just dropped anchor. His protestations and expressed desire to close the distance proved futile—the pilot would not go nearer. Resigned to the situation, Parker then hailed the Experiment and conveyed to Capt. Alexander Scott his opinion that they were at too great a distance and that he wanted Scott to take his ship in as close as possible. Experiment’s pilot not only refused, but imagining the Bristol to be as near as they ought to venture, anchored the Experiment on an outboard quarter.[20]

The man aboard Bristol upon whom Parker placed the blame was a freed black man named Sampson, a pilot with more than fifteen years experience in South Carolina waters. It was Sampson who, whether cajoled or threatened, obstinately refused to take the Bristol to within the desired distance of 150 yards of the shoreline. The pilots of the other ships apparently followed suit. Sampson’s rationale is difficult to discern. He had been in British service since July 1775 when he was taken aboard the Scorpion. Both deposed royal governor William Campbell and the current patriot governor John Rutledge considered him to be Charleston’s best harbor pilot, but perhaps he was unfamiliar with the water immediately off Sullivan’s Island, particularly the depth. Or maybe he was unaccustomed to piloting such a large, heavy man-of-war like the Bristol. Nor is it inconceivable that he was intimidated by the cannon fire from the fort and lost his nerve. In any event he was neither punished nor removed. Instead, so valuable was he to the Royal Navy that he was sent below deck and “put down with the Doctor out of Harm’s Way” for safety’s sake. Unlike Parker, Sampson came through the battle physically unscathed and with usefulness undiminished. He continued to guide British warships along the Georgia and South Carolina coast until he was captured aboard the Experiment by the French in 1779.[21]

Standing too far offshore had further negative consequences for the British attack. In accordance with Parker’s plan, about an hour into the bombardment the 20-gun corvette Sphynx and two 28-gun frigates Acteon and Syren, all comprising the second line-of-battle, set a westerly course for a new position off the fort’s right flank that would allow them to enfilade the patriot position and cut off the only possible avenue of retreat from the island to the mainland if the rebels were driven from their works and tried to escape. Moultrie’s position in the fort would become untenable and surrender would be inevitable since retreat would be virtually impossible.[22]

Instead of sealing the Americans’ doom the British would-be flankers, deprived of full use of the channel by the first battle line, ran aground on a sandbar that projected outward from James Island. The Acteon and the Sphynx ran afoul of each other as all three ships became stranded on the shoals (where Fort Sumter would later be built) southwest of the main line, rendering them not only incapable of accomplishing their mission, but completely useless for the rest of the fight. There just wasn’t room to

maneuver. Their pilots, whoever they were, had failed miserably and bear the burden of responsibility for the misadventure. This British mistake was providential for the South Carolinians on Sullivan’s Island. Moultrie noted that “had these three ships effected their purpose, they would have enfiladed us in such a manner, as to have driven us from our guns.”[23]

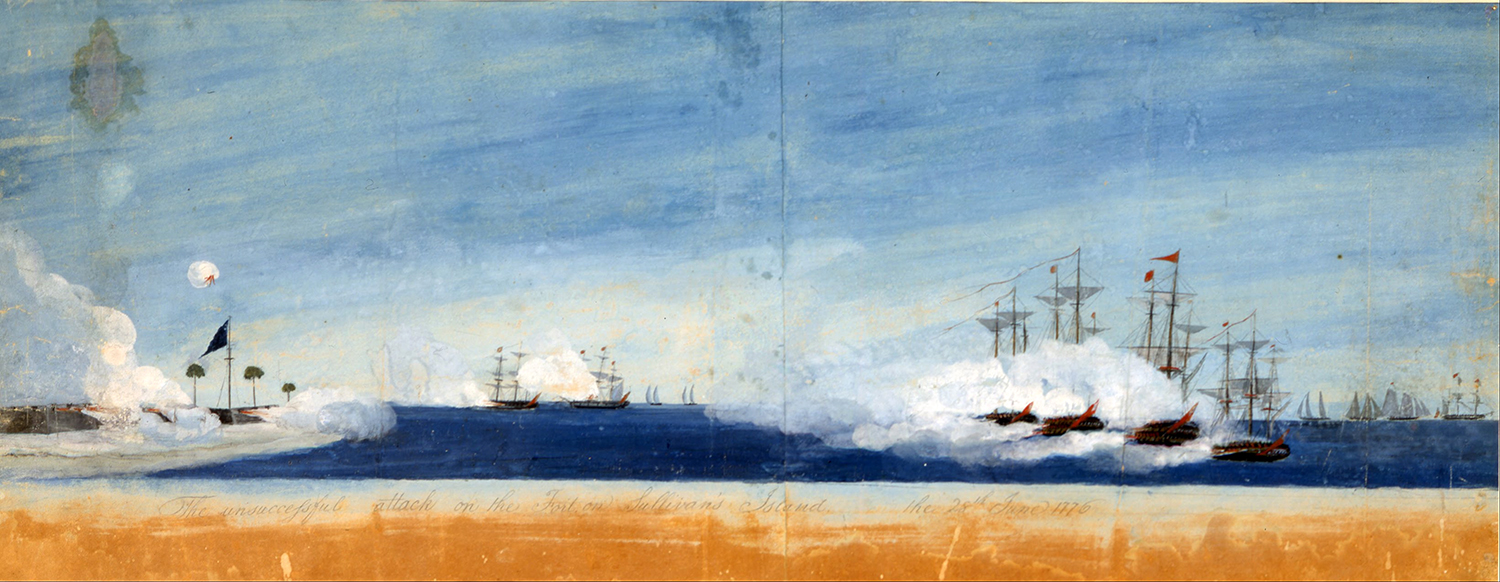

If Henry Clinton ever viewed English artist Nicholas Pocock’s 1783 painting A View of the Attack Made by the British Fleet Under the Command of Sir Peter Parker against Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island, June 28th, 1776, he would surely have vehemently objected to Pocock’s depiction of the attacking British ships closely engaged with the fort and firing their broadsides from near point-blank range. It is likewise improbable that Clinton ever saw a watercolor executed by Lt. Henry Gray soon after the battle. Had he done so he certainly would have appreciated Gray’s historical accuracy. Gray was present on the fort’s parapets on the day of the battle and his painting The Unsuccessful Attack on the Fort on Sullivan’s Island, the 28th of June, 1776, is a fairly accurate-to-scale rendition showing the ships firing on the fort from a distance.[24]

Clinton was enraged to learn that a report in the London Gazette implied that he was at fault for the disaster, that he had offered no alternative plan, and that he had remained idle on Long Island after finding Breach Inlet impassable at Sullivan’s Island. He blamed Lord George Germain and Sir Peter Parker for what he considered to be a cruel injustice and he spent almost a decade trying to set the record straight. For his part Parker, who was patient and conciliatory, tried to appease his aggrieved comrade, a task he found to be virtually impossible. Parker had concluded that the whole matter “best be consigned to Oblivion …. My wish is that not a syllable be ever mentioned in Publick about the expedition which is an affair now forgot and a Subject not pleasing to Revive.”[25]

Not withstanding the abortive British campaign in the South, for conspicuous gallantry during the capture of New York in later in 1776 Clinton was promoted to lieutenant general and knighted by George III. In 1778 he succeeded Lt. Gen. Sir William Howe as commander-in-chief of British forces in North America. While moving his army from Philadelphia to New York, Clinton fought Washington to a stalemate at Monmouth Court House on June 28, 1778, exactly two years after the British defeat in Charleston. It was his first and only pitched battle against the Continental Army.[26]

In March 1780 Clinton returned to Charleston with more than eighty-seven hundred British, provincial, and Hessian soldiers—the flower of the British army in North America. This time he would not be denied. Employing formal siege operations, by the end of April he had invested the town. Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, commanding the Southern Department of the Continental Army, refused to evacuate his troops before Clinton’s forces severed all avenues of escape and thus Charleston became the greatest disaster to befall an American army during the war. Lincoln surrendered his 5,600 Continentals and militiamen to the British on May 12, 1780.

Timidity on the part of the Continental navy during the siege of Charleston had resulted in Fort Moultrie being tamely given up without a contest. Eight British warships and a small assortment of other vessels sailed past on April 8, each man-of-war pausing only long enough to unleash a single broadside at the fort. The British subsequently landed five hundred sailors and marines on Sullivan’s Island during the night of May 4. They were preparing to take the fort by storm on May 6 when its commander, Col. William Scott, realized the futility of his situation and negotiated the fort’s surrender. Scott and his garrison relinquished the stronghold the next day. When the British victors marched into the fort, they “leveled the thirteen Stripes with the Dust, and the triumphant English Flag was raised on the Staff.” From his vantage in town looking across the harbor General Moultrie could see the British flag flying from Fort Moultrie’s flagstaff. Even though he was not surprised that the fort was lost, he was disgusted that it surrendered without firing a shot in its own defense, a vast contrast to the gallant stand he had made nearly four years earlier.[27]

On May 27 Clinton visited Sullivan’s Island for the first time. He concluded that if British marines and sailors had tried to storm Fort Moultrie they would have been repulsed with great loss even though the fort was only lightly manned. However he had interest beyond inspecting the captured fort—his ulterior motive when he went to the island was to prove to himself right about the navy’s ability to bring ships into close proximity with the fort during the 1776 battle. He reported in his journal that he “sounded the anchorage within 50 yards of Sullivan’s Island Fort at low water and found 5 fathoms and a quarter [31.5 feet]!!!” The channel was indeed deep enough for the fourth-rate 50-gun Bristol and the other ships-of-the-line to have engaged the fort at close range with the tide rising as it was at the time of the battle on June 28, 1776. Bristol was the largest and drew less than eighteen feet.[28]

Brimming with self-vindication, he wrote in a journal, if only for himself, “What say you now, S[ir] P[eter] Parker!” The remark is intriguing in light of Parker’s 1777 acknowledgment to Clinton that he would have very much liked to bring his battle line closer to the fort. One can only wonder if a disagreement remained between the general and the commodore concerning the depth of the channel. No documentation of such a discussion has been found and Clinton mentioned nary a word about channel depth in a detailed narrative that he published in 1780. Nonetheless he seems to have remained neurotically obsessed with the possibility of being blamed for the 1776 debacle, hence his compulsion to have himself rowed out into the water so he could personally sound the channel.[29]

Portions of this article have been extracted or adapted from C. L. Bragg, Crescent Moon over Carolina: William Moultrie and American Liberty (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2013) and C. L. Bragg, Martyr of the American Revolution: The Execution of Isaac Hayne, South Carolinian (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2016).

[1]. Henry Clinton and William T. Bulger, “Sir Henry Clinton’s Journal of the Siege of Charleston, 1780,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 66, no. 3 (1965): 174.

[2]. Ibid.

[3]. Leslie Stephen and Sidney Lee, eds., Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 4 (New York: MacMillan Co., 1908), 550–51; Henry Clinton, The American Rebellion: Sir Henry Clinton’s Narrative of His Campaigns, 1775-1782, with an Appendix of Original Documents, ed. William B. Willcox (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954), xvii; Frederick Wyatt and William Bradford Willcox, “Sir Henry Clinton: A Psychological Exploration in History,” William and Mary Quarterly 3rd ser., vol. 16, no. 1 (1959): 3–26.

[4]. Stephen and Lee, Dictionary of National Biography 4: 550–51.

[5]. George Godfrey Cunningham, ed., Lives of Eminent and Illustrious Englishmen from Alfred, the Great to the Present Time, On an Original Plan (Glasgow, Scotland: A. Fullerton & Co., 1840), 113–16.

[6]. William B. Willcox, Portrait of a General: Sir Henry Clinton in the War of Independence (New York: Knopf, 1964), 90, 124, 512; Wyatt and Willcox, “Sir Henry Clinton: A Psychological Exploration in History,” 26.

[7]. Eric Robson, “The Expedition to the Southern Colonies, 1775–1776,” English Historical Review 66, no. 261 (1951): 538–41; Clinton, American Rebellion, 23–28; Willcox, Portrait of a General, 81–86.

[8]. Clinton, American Rebellion, 28–30, 29n22; Robson, “The Expedition to the Southern Colonies,” 540–41, 551–55; William James Morgan, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution, vol.5 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1970), 573, 609; Edward S. Farrow, A Dictionary of Military Terms (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1918), 147; Willcox, Portrait of a General, 87.

[9]. Charles Lee, The Lee Papers, 1754–1811. Vol. 2, 1776–1778, edited by Henry Edward Bunbury, Collections of the New York Historical Society for the Year 1872 (1872), 80–81; William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution so far as it Related to the States of North and South-Carolina, and Georgia, vol. 1 (New York: David Longworth, 1802), 141.

[10]. Morgan, Naval Documents 5:573, 608, 609, 653, 782; Clinton, American Rebellion, 30–31.

[11]. Clinton, American Rebellion, 31–32 (quoted),32–33n29; Morgan, Naval Documents 5:608, 745.

[12]. Morgan, Naval Documents 5:999.

[13]. Moultrie, Memoirs 1:177n; John Drayton, Memoirs of the American Revolution, from its Commencement to the Year 1776, Inclusive, vol. 2 (Charleston: A. E. Miller, 1821), 326n; Robert Wilson Gibbes, Documentary History of the American Revolution (New York: D. Appleton, 1857), 17; Morgan, Naval Documents 5:1001.

[14]. Morgan, Naval Documents 5:802 (first quote); Gibbes, Documentary History, 9–10 (second quote).

[15]. Peter Parker to Henry Clinton, January 4, 1777, Henry Clinton Papers, 1736-1850, volume 20:6, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

[16]. Clinton, American Rebellion, 32–34; Morgan, Naval Documents 5:745, 999.

[17]. Moultrie, Memoirs 1:180; Clinton, American Rebellion, 35, 35n33 (first quote); Gibbes, Documentary History, 6, 8; Morgan, Naval Documents 5:796 (second quote)–99, 800, 801n3, 825, 841, 864; Clinton and Bulger, “Sir Henry Clinton’s Journal of the Siege of Charleston, 1780,” 157.

[18]. Morgan, Naval Documents 5:784 (first quote), 984 (second and third quotes); Henry Clinton to Edward Harvey, November 26, 1776, Henry Clinton Papers, volume 18:55.

[19]. Moultrie, Memoirs 1:170–71; Clinton, American Rebellion, 34–35.

[20]. Clinton, American Rebellion, 35, 35n33; Moultrie, Memoirs 1:171; Parker to Clinton, January 4, 1777, Henry Clinton Papers.

[21]. Kevin Dawson, “Enslaved Ship Pilots in the Age of Revolutions: Challenging Notions of Race and Slavery along the Peripheries of the Revolutionary Atlantic World,” in Jeffrey A. Fortin and Mark Meuwese, Atlantic Biographies: Individuals and Peoples in the Atlantic World (Boston: Brill, 2014), 170; Morgan, Naval Documents 3:539; Kevin Dawson, “Enslaved Ship Pilots in the Age of Revolutions: Challenging Notions of Race and Slavery between the Boundaries of Land and Sea,” Journal of Social History 47, no. 1 (2013): 87–88; Morgan, Naval Documents 5:861 (quoted).

[22]. Morgan, Naval Documents 5:999.

[23]. Moultrie, Memoirs 1:178.

[24]. Nicholas Pocock, A View of the Attack Made by the British Fleet Under the Command of Sir Peter Parker against Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island, June 28th, 1776, 1783, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, S.C.; Henry Gray, The Unsuccessful Attack on the Fort on Sullivan’s Island, the 28th of June, 1776, [1776], Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston, S.C.

[25]. London Gazette, August 24, 1776; Morgan, Naval Documents 5:999–1001; Willcox, Portrait of a General, 91–93, 124–25, 130; Clinton, American Rebellion, 36–37, 36n34, 376–79; Henry Clinton, A Narrative of Sir Henry Clinton’s Co-Operations with Sir Peter Parker, On the Attack of Sullivan’s Island, in South Carolina, in the Year 1776. ([New York: Printed by James Rivington (?),] 1780), 1–20; Clinton to Harvey, November 26, 1776, Henry Clinton Papers, 1736-1850; Parker to Clinton, January 4, 1777, Henry Clinton Papers, 1736-1850 (quoted).

[26]. George Athan Billias, ed., George Washington’s Generals and Opponents: Their Exploits and Leadership, vol. 2 (New York: Da Capo Press, 1994), 73–76; Stephen and Lee, Dictionary of National Biography, 4:550–51.

[27]. Moultrie, Memoirs 2:60–61, 63, 84–85, 84 n [†]; Clinton, American Rebellion, 169; Uhlendorf, Siege of Charleston, 283, 285; Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, In the Southern Provinces of North America (Dublin, Ireland: Colles, Exshaw, White, H. Whitestone, Burton, Byrne, Moore, Jones, and Dornin, 1787), 53, 55–57; Richard K. Murdoch, “A French Account of the Siege of Charleston, 1780,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 67, no. 3 (1966): 152, 152n53; Franklin Benjamin Hough, The Siege of Charleston, by the British Fleet and Army Under the Command of Admiral Arbuthnot and Sir Henry Clinton, which Terminated with the Surrender of that Place (Albany, N.Y.: J. Munsell, 1867), 166–69 (quoted); Lachlan McIntosh, Lachlan McIntosh Papers in the University of Georgia Libraries, edited by Lilla Mills Hawes (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1968), 118.

[28]. Clinton and Bulger, “Sir Henry Clinton’s Journal of the Siege of Charleston, 1780,” 174 (quoted); Clinton to Harvey, November 26, 1776, Henry Clinton Papers; Angus Konstam, British Napoleonic Ship-of-the-Line (Botley, Oxford, U.K.: Osprey Pub., 2001), 45; Morgan, Naval Documents 5:827–28; C. Leon Harris, “An Estimate of Tides During the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, S.C., 28 June 1776,” November 12, 2010, https://thomsonpark.files.wordpress.com/2010/06/tides-12xi10.pdf, accessed on March 28, 2016.

[29]. Clinton and Bulger, “Sir Henry Clinton’s Journal of the Siege of Charleston, 1780,” 174; Parker to Clinton, January 4, 1777, Henry Clinton Papers, 1736-1850; Clinton, A Narrative, 1–20.

One thought on “Why the British Lost the Battle of Sullivan’s Island”