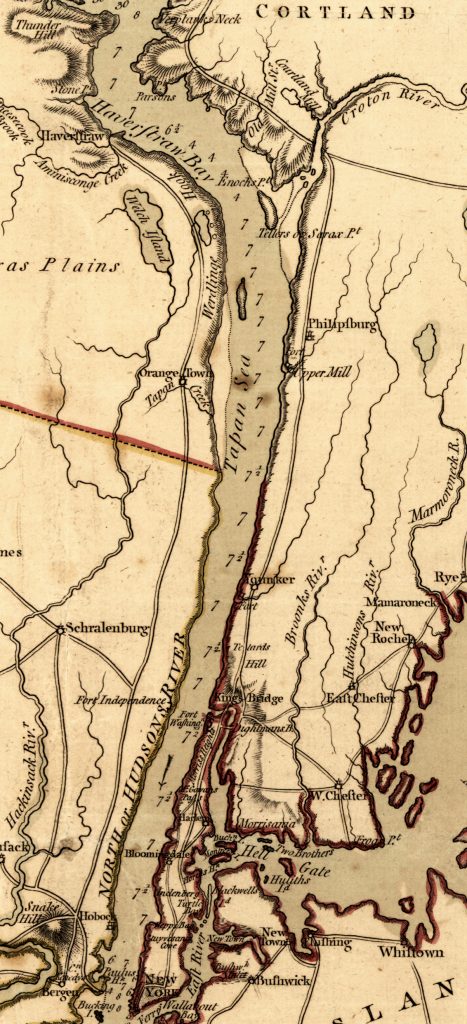

Gen. George Washington, commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, arrived at the American defenses at West Point “very much fatigued.” He had ridden one his two beloved mounts, either Nelson or Blueskin, nearly fourteen miles over rugged hills. It was late afternoon on July 19, 1779, and Washington was just getting settled after “returning from Stony Point,” as he informed Gen. (and Governor of New York) George Clinton. The previous day, the Americans had “dismantled the works at Stony Point . . . and last night destroyed them as far as circumstances would permit;” days earlier, the Continental Army had taken possession of Stony Point, a rocky peninsula jutting out from the west shore of the Hudson River. The British had landed there and directly across the river at Verplanck Point on June 1 and fortified both points. After nearly three weeks of deliberation and planning, Washington and one of his fightingest officers, Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne, came up with and brilliantly executed an assault on Stony Point in the wee hours of July 16. From the assault to Washington’s departure (he had arrived on July 17), the dead were buried, the prisoners marched off, and goods carried away, while the developing assault on Verplanck crumbled in the face of advancing British forces. Col. Richard Butler, third in command of the Corps of Light Infantry, the unit that assaulted Stony Point, reported to Washington that hours after the commander-in-chief had departed, the Americans also left, only to see right behind them the British land on Stony Point after a brief bombardment to “Cover their landing . . . they took immediate possession of the Point . . . & Confined themselves within their Sentries.”[1]

British Brig. Gen. Thomas Sterling landed his brigade, consisting of the 42nd Royal Highland, the 63rd, and 64th Regiments of Foot, for the night of the July 19. In the next few weeks, they would begin construction of a new fort on the point with a very different design from the original. The Americans, however, did not let this go unnoticed. From headquarters at West Point, Washington wrote to two of his officers on July 25. He asked Col. Richard Butler to gather information on the British, to be as “particular & critical” as he could in “ascertaining the several Works the Enemy are carrying on—their number and nature—whether inclosed or otherwise.” Numbers of tents were important too, he directed, as that would help form “an estimate of their force.” He asked twenty-three-year-old Maj. “Light Horse” Henry Lee, who commanded his own legion, to “obtain the most precise ideas of the situation at Stony Point . . . I wish to know upon what plan the enemy are now constructing their works . . . what is the strength of the garrison, the corps that compose that strength the number and sizes of cannon, [and who] commands.” Gathering detailed intelligence was not something new to Washington, and in this case he had pressing reasons for it, for on the following day, he summoned a council of his general officers. The commander-in-chief requested that his generals reply to him in writing with their opinions on the following question: Do we attack the British at Stony Point again?[2]

Sixteen of Washington’s generals returned written replies. Following are the core answers from each letter. The generals who answered in the affirmative:

Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne: “I have fully Considered & am of Opinion that something ought to be attempted in order to draw Genl [Henry] Clinton’s attention towards King’s Ferry, which will not only give great Security to the Adjacent States-but leave it in your power to cover [West Point].”

Brig. Gen. William Irvine: “My Opinion is that we should not lose any opportunity—(where there is a rational prospect of success) of Attacking them by Detachments . . . the infant state of their works on Stony Point renders it in my Opinion practicable—I am for Attacking it.”

Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair: “[It] may . . . be carried by Surprize, which seems to me the only eligible Method all things considered.”

Maj. Gen. Robert Howe: “To attack, or if that is not eligible, to hover about their favourite Posts might oblige them to k eep a large Body of Troops in and about their Works, to the Dimunation of their Main Body . . . if it can be done without too much risque.”

Maj. Gen. William Heath: “Stony and ver planks points are Vulnerable, the works at the former being as yet incomplete maybe attacked by assault & perhaps carried, tho’ it is to be supposed that the Enemy from his late misfortune . . . will make an Obstinate resistance . . . [it] should not be purchased at too dear a rate.”

Brig. Gen. Mordecai Gist: “I am of Opinion that a Movement of part of our Army on each side of the River within supporting distance of this post to show a disposition of attack on their Works, may in some measure counteract their scheme of plundering.”

Brig. Gen. Samuel Parsons: “If we can procure a Sufficiency of Military Stores for the Purpose . . . an attempt to dispossess the Enemy of Verplank’s and Stony Points ought to be attempted . . . if this Enterprize Should be undertaken both Sides of the River should be attempted at the same Time because the Post on the east side cannot be carried whilst the Enemy remain posses’d of Stony Point.”

Maj. Gen. Baron de Kalb: “As to Stony Point . . . we Should interrupt and retard their Works and Strike a Blow there—if it can be done with any prospect of Success.”[3]

The following generals urged caution and voiced a preference to not attack.

Maj. Gen. Baron von Steuben: “I am not of opinion to hazard a second attempt upon the same point . . . [yet] the more of their force we can keep at bay here, the less they can employ in operations elsewhere.”

Brig. Gen. William Smallwood: “At present I should judge it more expedient to hold out appearances of attacking or annoying their Garrisons.”

Brig. Gen. John Nixon: “Considering the Great Effusion of Blood in taking Stony Point, it might more than Countervail the advantage we Should Gain thereby . . . unless upon both [points] at the same time.”

Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene: “I cannot think a second attack upon Stony Point would be crowned with the same success as before; and our Army is not in force to make a great sacrifice of men by way of experiment, or for the purpose of giving Military glory to individuals.”

Maj. Gen. Alexander McDougall: “The present Strength of thee Garrisons and works at Kings ferry are such, as renders a Second attack by Storm on either of them very Hazardous, and would in all Probabil[ity] . . . cost us more men, than the acquisition.”

Brig. Gen. Henry Knox: “An Attempt on Verplanks or Stony point has been mention’d as an elig[i]ble circumstance. I confess I do not see the Advantage of such an attempt . . . Stony Point from its peculiar situation appears to be out of the question.”

Brig. Gen. Louis Duportail: “I think that we ought to not attack them, because we should be likely to lose a good many men and perhaps without success—Besides, . . . we should not have any great advantage by gaining possession of Stony Point, because we must also be masters of Verplanks . . . if we should attack Stony Point . . . we must not believe, that we should succeed in the same manner a second time.”

Brig. Gen. Jedediah Huntington: “That an attack . . . [on] the Posts at Kings ferry would occasion too great an Expenditure.”[4]

The council was split down the middle. Privately, Washington wrote to Anthony Wayne. He wrote that he wished for his “opinion as a friend, not as commanding officer of the light Troops—whether an attempt on Stony Point by way of surprize is eligible.” The following day, Wayne replied, noting that the “Enemy will certainly profit so far by their late misfortune . . . as to provide for, or against a Surprize.” The British “were at this time Industriously employed” in strengthening their defenses. However, Wayne thought that his “Light Corps with the addition of One Thousand more picked men & Officers properly Appointed would cary that post by Assault in the night with the loss of between four & five Hundred men . . . supposing the Enemy to be but One Thousand strong.” If Washington agreed, Wayne offered himself “with the greatest chearfulness [to] under-take the charge, altho’ I am not quite Recovered of my former hurt,” referring to his wound from July 16. Wayne would not get his second chance; Washington erred on the side of caution and instead of making an assault, continued to monitor activity at King’s Ferry.[5]

While the Americans deliberated on attacking again, the British kept on working. Once reestablished at Stony Point, it was evident a new system of defensive works were necessary. To that end, Capt. Patrick Ferguson of the 70th Regiment of Foot, inventor of the Ferguson rifle, who had been stationed at Verplanck Point since June, was handed the job. As Capt. Archibald Robinson recalled, at a meeting with Gen. Sir Henry Clinton and other officers, “Capt. Ferguson undertook to finish [the works] in 14 days then got 8 more added, then the General sent him up from Camp.” This was not Ferguson’s first time thinking of ways to redesign Stony Point. At some time in late June or early July, Capt. Robert Douglas of the Royal Artillery recalled a meeting in which Ferguson “from the first Moment disapproved of the Mode, in which Stony Point was fortified; it was his almost constant conversation in my hearing.”[6]

Apart from some gunboat activity in August, the Stony Point side of the Hudson River remained fairly quiet. On September6 , with British defenses well under way, Wayne reconnoitered the post. He reported to Washington that the British had “nearly Completed their works—which Consist of One Advanced Redoubt on the Hill Commanding the ferry, way encloses & finished with a good Abbatis & Block House.” Their main work, confined to the higher ground on the point, was also

Enclosed the parapet raised much higher than usual & fraised in the most Capital manner & surrounded with a wide & formidable Abbatis—within this is a Citadel Independent of the Other work with a Strong high parapet (with fraised) and a Block House which (fires) in Barbett the top of all the parapets neatly & almost Completely (sodded). They have about Eight Guns mounted.

Wayne was impressed: “They have appearantly done more work . . . than all our Army have Effected the whole Campaign.” Ferguson himself was pleased with his work, and wrote to General Clinton saying, “at Stony Point it has been our Endeavour to Secure the Post against a surprize or Coup de Main by Multiplying the Obstacles on the Grounds by which the works are to be approach’d.” He further reassured the British commander-in-chief that, “I flatter myself you need not apprehend any Danger . . . & if your Excellency will allow the Thirty Pioneers now here to remain another fortnight we shall be so bury’d in abatti, that the Garrison will not be obliged to be harass’d upon every alarm.” Days later, another of the aforementioned alarms took place. On September 22, Sgt. Henry Nase of the King’s American Regiment noted that “a large Body of rebells appeared Before the Lines.” Maj. Charles Graham of the 42nd Regiment, who had commanded Stony Point during its reoccupation, that same day wrote to Clinton that at about ten in the morning, “a very large body of Rebells . . . appeared drawn up on the Rising grounds about three Quarters in our front,” not doing much until night, when they “kept up a popping [firing muskets] from the Woods.” The most likely candidate for this force of Americans was Wayne’s Corps of Light Infantry, as they were the only sizeable unit in the vicinity of Stony Point.[7]

Just four days later, Washington wrote to Wayne that “General Knox and du Portail are to go down to night, or early to-morrow to reconnoitre the enemy’s post at Stony Point,” and that they would expect him to join them. General Knox, commander of the Continental Army’s artillery, reported their adventure to Washington on September 30. After initially taking a “general view . . . from the Donderburgh [Dunderberg Mountain],” they then got dangerously close, at a “piece of Ground which we estimated at about 800 yards distance,” barely out of range for a light cannon. Knox noted that there were a few eligible places north and west of Stony Point to open batteries, but to really pummel the post into submission, “it would be necessary to have 15 or 16 heavy Cannon and eight or ten mortars and howitzers,” and that it would take at least a “ten days Siege.” Luckily though, the Enemy [had] demolished a number of their Works on Verplanks point.”[8]

On September 27, just as the Hudson Valley began to shake off the summer heat, Captain Ferguson was handed a devastating letter to which he immediately replied, pouring out his frustrations. To his commander-in-chief, he wrote that,

Your letter was put into my hand by Major Graham an hour ago . . . After having so long exerted myself to the utmost & been a witness of the zeal & perseverance with which the Troops have labor’d to put this Post out of reach of Insult, it is with the Greatest Pain I read . . . that Circumstances may oblige us to abandon our Works to the rebels.

Ferguson’s harangue went on for another seven paragraphs before closing with the wish that his recipient would “pardon the warmth with which I have express’d myself.” In a postscript, he wrote “May I beg to know your Determination [on maintaining the post] soon, to prevent unnecessary labor.” The demolition of the out works at Verplanck that Knox noted was the first stage of Clinton’s reduction of the posts at King’s Ferry. Despite the shrinking of forces, Stony Point was still sufficiently strong, at least to Ferguson. In a letter to Capt. John André, he boasted that Stony Point had a “Compliment of iron Ordinance to two 18’s & six 4’s, Exclusive of the Rebel 32 [pounder] & a 24 [pounder] still here which wants . . . a Carriage.” On October 3, Washington wrote Wayne that “General Du Portail proposes tomorrow to reconnoitre a second time the post of Stony Point,” and to meet him at eleven in the morning with a “Regiment ready,” or one fourth Wayne’s force to cover them, and also to take special care to see if the enemy had any “bomb proofs in Stony Point, what number, extent and thickness.” Washington was once again seriously considering an attack on Stony Point; he wrote to Gen. Arthur St. Clair that “if the Posts on the North [Hudson] River are not drawn in, I suppose two thousand Men, with proper Artillery might, in a Week reduce Stony Point without . . . much upon the greater Operations of the Army.” On the same day, Washington wrote to Gen. William Alexander, known to the Americans as Lord Stirling, that the “prospect of preventing the retreat of the garrisons at Stony and Verplanks (so far as it is to be effected by a Land operation) again revives upon probable ground.”[9]

On October 9, Wayne reported on the second reconnoitering of Stony Point, “Enclosed is a plan of the Enemies works . . . taken by Colo [Rufus] Putnam with the points of attack in case of Investiture.” The enemy,

Have neither Bomb proofs- nor a Magazine, their Ammunition is kept on Board a Sloop in the rear of the point except a few rounds . . . Covered by two tents-they have a 32 pounder mounted on their Right . . . one 18 on their left . . . a few fives [and] Sixes [actually 4 pounders] & four 5 [1/] 2 & 42 inch [?] Howitz at Intermediate distances between the two extremes where the 32 & 18 pounders are & in Block Houses.

Wayne then described his thoughts on how any type of siege might progress. He thought that “two 18 & two or three 12 pounders on travelling Carriages with two 8 inch Howitz[ers] would be a sufficiency of Artillery to reduce this post.” A “Combined attack on verplanks point ought to take place at the same time . . . I think we should carry the Works by storm with great care.”

Generals Wayne and Duportail’s snooping about did not go unnoticed. It alarmed Captain Ferguson, who wrote to Clinton on October 9, “Since . . . I did myself the honour of writing on the 6th we have passed some anxious moments. The rebel movements . . . [indicate] a Design of Attacking these Posts.” Despite the earlier order to withdraw defenses, Ferguson was still genuinely concerned with the security of the posts. Desertions, he maintained, were a problem but siege worried him more. Correctly, he estimated that the Continental Army would utilize a “design of distressing by Shells & not withstanding that I have done my utmost to secure us,” for “the Proximity of the rebel army & Labour of procuring . . . heavy trees has prevented our being as yet in great degree defended.” The next day, Washington acknowledged Wayne’s letter, but urged caution. “It is not to our Interest to disturb the enemy,” but that they should be “lulled into security, rather then alarmed.” The usually decisive Washington could not make up his mind.[10]

Down towards headquarters in New York, Capt. John Peebles of the 42nd Regiment’s grenadier company noted in his diary, “Tuesday 12 Octr: strong [Southerly] wind. The Com[mander] in chief gone up to Stoney Pt. with the [HMS] Fanny & some small craft.” Wayne noticed the arrival of these new vessels. A few “Ships & other Vessels made their Appearance . . . I have sent down to try to Discover whether they have brought a Reinforcement . . . or [are] preparing for an evacuation.” The next day, October 14, Washington replied to Wayne that “a deserter from the [HMS] Vulture sloop the day before yesterday informs that Sir Henry Clinton . . . and several other officers came up the River.” A week passed with little to report on either side. Suddenly, on October 21, Wayne fired off to Washington that the previous evening he gained “Intelligence that a number of flat Bottomd boats & Several vessels were moving up Haverstraw Bay—the troops were Ordered to lay on their arms,” for “some Capital move was in agitation,” but whether coming or going Wayne could not decipher. All was quiet until daylight, when Wayne “could observe them busily employed in Imbarking their Baggage & Cannon—About 10 O Clock they began to Demolish their parapets & fraise on Verplanks.”

On Stony Point, however, they had not yet begun, and Wayne was determined to “prevent them from Demolishing the face of their works . . . [although] they will probably burn or blow up their Block Houses.” He then waxed triumphant, assuring his commander that he’d only “keep a Captains guard at Stony Point . . . for be assured the [works] will be in our possession this Night—the moment we enter them I shall Announce it by the firing of five Cannon—observing the time of half a Minute between each gun.” Washington, already composing a letter to his favorite aide, Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton, who was on a mission with General Duportail in New Jersey, told them he had just received a line from Major General Heath, and that “the Enemy have left both points having burnt & destroyed their Works;” with that, the British peacefully departed their works at King’s Ferry which, except for Stony Point for under four days, had been theirs for almost five months. Washington told his two closest commanders, Wayne at Stony Point and Heath near Verplanck, to be ready for his arrival at eight in the morning on October 23. Crossing in the mail was Wayne’s brief report to Washington that at Stony Point, “all the Block houses are Destroyed with some of the fraizing & parapets, but the far greater part is perfect, & very little of the Abbatis Injured.” Until he heard otherwise, Wayne kept his promise that he’d “Keep a Captains Guard at Stony Point in the day time.” By now, news of the change in possession of King’s Ferry had reached the British, specifically Hessian Jäger officer Capt. Johann Ewald, who commented, “We have again abandoned the posts of Stony and Verplank’s Point . . . [the Americans] already taken possession of them . . . Once more, we are no further than we were at the beginning of the campaign.” Frustrated at Lt. Col. Henry Johnson’s loss of Stony Point back in July, he said, “How easily can the plan of an entire campaign be upset by the negligence of an officer to whom a post is entrusted!”

After his inspection of the points of King’s Ferry, Washington returned to West Point where he told General Heath that to “protect the communication by Kings Ferry, I think the Connecticut Division may as well move down as low as . . . Pecks Kill [Peekskill].” He would “direct Colo [Jean-Baptiste] Gouvion to lay out two small Works at Verplanks and Stoney points,” and ordered that the Connecticut men would supply the work parties on the eastern shore. On the west side, Wayne was given similar instructions, and to “furnish a party from the [Light] infantry,” and to coordinate with Gen. William Woodford who would “furnish a party from the Virginia line also.” As the “Work will be trifling,” Washington said, he wished that “the parties may be as such as will finish it out of hand.”[11]

The following day, Washington received intelligence that the British had landed troops near Amboy in New Jersey, and consequently, the Light Corps and Woodford’s Brigade were sent off to shift towards that area. Because of this shift, Washington asked Heath to send some of his Connecticut troops to Stony Point to pick up the slack. With the British gone for a week now, it was time to reestablish the normalcy at King’s Ferry that had been absent since June. From his headquarters at Peekskill, Heath issued a series of orders regarding Stony and Verplanck Points. Heath ordered “two Sentinels,” on each of the points “as will best facilitate observation. They are to . . . keep a Watchful Eye down the river & Should they perceive any Vessell . . . to give notice” immediately. In addition, “two men will patrole in the Neighboorhood of each point,” and a “Sentinel . . . is to be posted at each Ferry ways to examine passengers & prevent any unknown persons from passing without passports from proper Authority.” Such persons as did not pass muster would be “detained & report made without Delay to a General Officer. No stranger is to be suffer’d to enter the works unless known & attended by a Commissioned Officer.” The Continental Army wasn’t sure at the time, but Stony and Verplanck Points would never be contested again. The Americans would have full control of King’s Ferry until relinquished at some point in late 1783. King’s Ferry would go on to play roles in the Arnold-André affair, host the Grand Encampment of Autumn 1782, and see Count Rochambeau’s Expeditionary Force cross the river twice.[12]

[1]George Washington to George Clinton, July 19, 1779, Founders Online (FO), founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0462; Michael J. F. Sheehan, “The Unsuccessful American Attempt on Verplanck Point, July 16-19, 1779,” Journal of the American Revolution, September 10, 2014, allthingsliberty.com/2014/09/the-unsuccessful-american-attempt-on-verplanck-point-july-16-19-1779/; Richard Butler to George Washington, July 19, 1779, Founders Online, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0461.

[2]Sir Henry Clinton to Lord George Germain, July 25. 1779, in Henry P. Johnston, The Storming of Stony Point on the Hudson, Midnight Jul 15, 1779 (New York: James T. White & Co., 1900), 123-5; Washington to Butler, July 25 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0530; Washington to Henry Lee, July 25, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0563 Note 2;, Alexander Hamilton to Nathanael Greene, July 25, 1779, FO, founders.archive.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0339.

[3]Anthony Wayne to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0571; William Irvine to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/doucments/Washington/03-21-02-0557; Arthur St. Clair to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0564; Robert Howe to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0555; William Heath to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0554; Mordecai Gist to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0552; Samuel Parsons to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0563; Johann de Kalb to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0559.

[4]Friedrich von Steuben to George Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0567; William Smallwood to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0566; John Nixon to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0562; Greene to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0553; Alexander McDougall to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0561; Henry Knox to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0560; Louis Duportail to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0551; Jedediah Huntington to Washington, July 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0556.

[5]Washington to Wayne, July 30, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0596. Wayne to Washington, July 31, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0604. With the addition of 1,000 men, Wayne’s strength would grow to near 2,300 men and officers.

[6]Archibald RobertsonHis Diaries and Sketches in America, ed. Harry Miller Lydenberg, (New York: New York Public Library, 1930), 200; Testimony of Capt. Robert Douglas in the Court Martial of Lt. Col. Henry Johnson in Don Loprieno, The Enterprise in Contemplation: The Midnight Assault of Stony Point (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2004), 297.

[7]Anthony Wayne to George Washington, September 7, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-01-0303; Patrick Ferguson to Henry Clinton, September 18, 1779, “An Officer Out of His Time: Patrick Ferguson,” in Howard Peckham, ed, Sources of American Independence: Selected Manuscripts from the Collections of the William L. Clements Library, Vol II, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975), 329; Diary of Henry Nase, King’s American Regiment, Nase Family Papers, New Brunswick Museum, 7, transcribed by Todd W. Braisted, kiltsandcourage.com; Charles Graham to Henry Clinton, September 22, 1779, Sir Henry Clinton Papers, Vol. 68: 45, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, transcribed by Paul Pace, kiltsandcourage.com.

[8]Washington to Wayne, September 26, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0435; Knox to Washington, September 30, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0471.

[9]Patrick Ferguson to Henry Clinton, September 27, 1779, in Peckham, Sources of American Independence, 330-2; Ferguson to John André, undated October 1779, ibid, 332-3; Washington to Wayne, October 3, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-01-0506. Bomb proofs are generally blockhouses sunk into the ground and covered with sod to absorb the shock of exploding mortar and howitzer shells; Washington to St. Clair, October 4, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0502-0006; Washington to Lord Stirling, October 4, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0502-0008;

[10]Wayne to Washington, October 9, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0561. Wayne’s reference to a forty-two inch howitzer is either his or an editorial mistake, as the largest shell throwing weapon of the war was a thirteen inch, and even they were traditionally mounted on a boat, and so he must mean a 4 ½, sometimes written 4 2/5, inch mortar, known as a cohorn. His reference to a fifty-two inch should likewise read 5 2/5 inch, or a Royal mortar/howitzer. Since the cohorns are usually mounted at an angle as mortars, perhaps they were mounted as howitzers, at a straighter angle, which may have confused him; Ferguson to Clinton, October 9, 1779, in Peckham, ibid, 334-6; Washington to Wayne, October 10, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0573.

[11]John Peebles, John Peebles’ American War: The Diary of a Scottish Grenadier, 1776-1782, Ira D. Gruber, ed.(Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998), 299; Wayne to Washington, October 13, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0592; Washington to Wayne, October 13, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0600; Wayne to Washington, October 21, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0652; Washington to Louis Duportail and Alexander Hamilton, October 21, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-022-02-0508; Washington to Wayne, October 22, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-23-02-0011; Washington to Heath, October 22, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-23-02-0003; Wayne to Washington, October 22, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-23-02-0012; Johann Ewald, Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal, Joseph P. Tustin, ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1979), 179; Washington to Heath, October 24, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-23-02-0024; Washington to Wayne, October 26, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-23-02-0054.

[12]George Washington to Heath, October 27, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-23-02-0058; Note 1, General Orders, October 29, 1779, FO, founders.archives.gov/doucments/Washington/03-23-02-0079; Michael J. F. Sheehan, “Top 10 Events at King’s Ferry,” Journal of the American Revolution, August 24, 2015, allthingsliberty.com/2015/08/top-10-events-at-kings-ferry/.

5 Comments

Stony Point is a historic site well maintained by New York state and well worth a visit. Mike, thank you for a most interesting, and well documented, article. As you probably know, the attacked on the Point was aided by numerous intelligence collection activities and the Culper Ring in New York City was able to provide timely British reaction to the brief American occupation.

Hi Ken- I’m not sure I’ve ever seen any Culper related intelligence regarding Stony Point. Do you have a letter or source you could provide? It would be fascinating to see!

Mike, see Morton Pennypacker, “General Washington’s Spies in Long Island and in New York”, pages 52-53. 2005 edition by Scholar’s Bookshelf for this information.

Testimony of Maj. Charles Graham, Commanding, 42nd or Royal Highland Regt.,

at Court-Martial of Lt. Col. Henry Johnson, 17th Regt., Regarding

Fortifications of Stony Point, New York, July 21- Oct. 23, 1779,

…Major Charles Graham of the 42nd Regt of Foot, being duly sworn, was Examined [Jan. 2, 1781].

Q. By Lt. Col. [Henry] Johnson [17th Regt.] As You Commanded at Stoney Point after that Post was repossessed by the British Troops, can you from your knowledge of the Ground & Works say, Whether the Plan now produced before the Court is a just One?

A. I can’t possibly say that it is a just Plan, but it appears as exact a representation of the Works thrown up as I can recollect; there were some trous de Loups under the Block House at the barrier on the left of the Works, which I do not Observe to be inserted in the Plan.

Q. Can you describe the State of the Works, as laid down in the Plan from the Retaking Possession of Stoney point to the time of your quitting it?

A. Brigr. Genl. [Thomas] Sterling’s Brigade Retook Possession of Stoney Point about the 21st or 22d of July & found the Works dismantled & the Abbatis torn up, & the Platforms destroyed; that we immediately began upon the defence of the Post, first by carrying as Abbatis round the Table of the Hill, & then erecting the enclosed Work, with Six Block Houses, as delineated in the Plan; that the Work upon the Table of the Hill being enclosed, a Block house was built in front upon a Know where there had latterly been a fleche.

Q. What time did it take to enclose the Work before the Block House in front was began?

A. I cannot exactly recollect; but I know that it was enclosed before Brigr Genl. Sterling left the Post, which was in about Six or Seven Weeks afterwards, when I was left to Command there.

Q. What Number of Men were left at Stoney Point under your Command, upon Genl. Sterling & his Brigade leaving it?

A. Including Pioneers & Batteaux Men (to whom we gave Arms from the Sick of the Garrison, as also Assigned Alarm Posts) about 1200 Men, between the Posts of Stoney & Verplank’s Point; the Number at the former was sometimes varied, but generally consisted of 5 or 600 Men.

Source and Notes: TNA, Court of Inquiry of Lt. Col. Henry Johnston, 17th Regt., Judge Advocate General’s Office: Court Martial Proceedings at WO71/93, pp. 1-137 as transcribed in The Enterprise in Contemplation: the Midnight Assault of Stony Point, Don Loprieno, Heritage Books, Berwyn Heights, MD, 2004, pp. 301-302. Lt. Col. Henry Johnson, 17th Regt. was in command of the Post at Stony Point when it was taken in a night attack by forces under the command of Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne on the night of July 15-16, 1779. Brig. Gen. Thomas Stirling was also the Lt. Col. of the 42nd Highlanders. The 42nd Highlanders were part of the garrison of Stony Point from July 19-Oct. 23, 1779. (Note per Merriam-Webster Dictionary: Trou de loup: a pit in the form of an inverted cone or pyramid having a pointed stake in the middle and forming one of a group constructed as an obstacle to the movements of an enemy. Plural: Trous de loup. Literally: “wolf hole.” Source:merriam-webster.com/dictionary/trou-de-loup.)

Well-written and researched article about a period of Stony Point history hardly ever covered.