Maj. Patrick Ferguson’s rifle is one of the most interesting and significant early attempts at a breech-loading service rifle. Coupling a screw breech plug with rifling, Ferguson’s rifle was said to be capable of an impressive seven rounds per minute. Most importantly it has the distinction of being the first breech-loading rifle adopted for service and used in action by the British Army. In an age when three or four rounds a minute from a trained infantryman was regarded as an impressive standard, six, or even seven, accurate shots a minute had the potential to be tactically ground breaking.

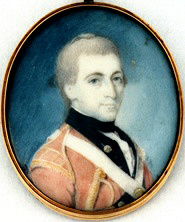

Born in Aberdeenshire in 1744, at fifteen Ferguson was commissioned as an officer in the Royal North British Dragoons, known as the Scots Greys. Cornet Ferguson then spent two years at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, an institution that specialised in training artillery and engineer officers, an indication of the young man’s intelligence.[1]He first saw action during the Seven Years War in Europe. In 1768, seeking advancement, Ferguson sold his cornetcy and transferred to the 70th Regiment of Foot, buying a commission as a captain and serving in the Caribbean for several years.

In 1771, the British Army introduced dedicated light infantry companies to each infantry battalion; Captain Ferguson was given command of the 70th Foot’s light company. Initially, the British Army’s light infantry arm was merely “light” in name with little specialist training given.[2] In 1774, Ferguson and his company spent the summer at Maj. Gen. William Howe’s light infantry training camp, learning how to deploy and fight as skirmishers.[3]

Ferguson was part of a generation of active, intelligent, professional and ambitious British light infantry officers. The light infantry arm of the British Army in the 1770s and 1780s was arguably one the most able elements of its day. Ferguson was reputedly one of the army’s finest marksmen and by the time he arrived in North America he was well versed in the light infantry tactics of the day, including skirmishing, scouting and irregular warfare.

It is believed that Ferguson began developing his rifle shortly after his time at the light infantry training camp. His rifle, however, was not the British Army’s first experimentation with a screw plug breech-loader. In 1762, John Hirst had provided the Board of Ordnance with five breech loaders; twenty more were reportedly ordered but they never saw service.[4] Twelve years later, in 1774, Ferguson started working on his rifle, commissioning Durs Egg, a renowned Anglo-Swiss gunmaker, to produce a slightly improved version of Isaac de la Chaumette’s screw plug breech loading action. La Chaumette had originally developed his screw breech rifle in the early 1700s, with his “Fusil qui se charge par la culasse” or roughly translated “rifle which is loaded by the breech” first appearing in 1704.[5] La Chaumette came to Britain as a Protestant refugee and patented some of his firearms designs in 1721. Several years later Michael Bidet built a sporting gun for King George II using La Chaumette’s screw breech system.[6]

In principle Ferguson’s rifle was similar to a number of earlier screw breech rifle designs which preceded it. In addition to La Chaumette’s system, numerous British gunmakers produced screw breech guns including John Warsop, Joseph Griffin, John Hirst, Joseph Clarkson and George Payne.[7]

While clearly not unique, Ferguson made a number of improvements to La Chaumette’s earlier work, principally by introducing a multi-start perpendicular screw breech plug with ten or eleven threads at one pitch. This meant the breech could be opened by completing just one full revolution of the trigger guard which was attached to the base of the plug, and acted as a lever. While it might be expected that fouling from powder residue or from dust and dirt might quickly seize up the screw breech, Ferguson designed the screw to have a number of recesses and channels to provide a place for fouling to go during use, and while not noted in contemporary sources the plug itself could be lubricated.

Ferguson’s breech plug was also tapered at a ten or eleven degree angle, making it less prone to fouling but still able to create an adequate breech seal. Unlike most contemporary rifles pressed into service Ferguson’ rifle could mount a bayonet and also had an adjustable rear sight—the first of its kind to see service. In 1775, Ferguson began lobbying senior officers including Lord Townsend, the Master General of Ordnance. He told Townsend in a letter that his rifle “fires with twice the expedition, & five times the certainty, is five pounds lighter and only a fourth part of the powder of a common firelock.”[8]

British encounters with rebel militia and especially with riflemen in America during 1775 fuelled interest in the adoption of suitable rifles for British service. In the summer of 1776, American Gen. Charles Lee wrote that “the enemy entertain a most fortunate apprehension of American riflemen.”[9] As a result, 1,000 German Jaeger-pattern rifles (described as the Pattern 1776 Infantry Rifle by firearms historian De Witt Bailey) were ordered in late 1775.[10] In April 1776, Ferguson’s attempts to interest to British Army’s senior officers in his breechloading rifle began to bear fruit. Ferguson was allowed to demonstrate his gun before senior officers on the April 27, 1776.[11] He fired at targets at 80, 100 and 120 yards away and “put five good shots into a target in the space of a minute.”[12] Durs Egg was directed to make improvements and two more rifles were built; Egg appears to have had a close working relationship with Ferguson with several of the surviving rifle’s being Egg-made guns.[13]

Ferguson never claimed to have invented the breech system himself, writing that “altho the invention is not entirely my own, yet its application to the only Arm where it can be of use is mine, and moreover there are several original improvements . . . which are entirely mine.”[14] As such Ferguson’s subsequent patent, filed in December 1776 and granted the following March, is titled “Improvements in Breech-loading Fire-arms.”[15]

In the early hours of Saturday, June 1, 1776, Ferguson was advised that Lord Townsend along with Gen. Lord Jeffery Amherst (the Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance), Lt.Gen. Edward Harvey (the Adjutant-General) and Lt. Gen. Thomas Desaguliers (of the Royal Artillery) wished him to demonstrate his rifle at Woolwich later that morning. The morning was wet and windy but Ferguson put on a display of shooting which is still widely regarded as an impressive feat.

An account of the demonstration was published in the Annual Register, a yearly almanac of notable events;

under the disadvantages of heavy rain and a high wind, performed the following four things, none of which had ever been accomplished with any other small arms. 1st, He fired during four or five minute at a target, at 200 yards distance, at the rate of four shots each minute. 2dly, He fired six shots in one minute. 3dly, He fired four times per minute advancing at the same time at the rate of four miles in the hour. 4thly, He poured a bottle of water into the pan and barrel of the piece when loaded, so as to wet every grain of the powder, and in less than half a minute fired her as well as ever, without extracting the ball. He also hit the bull’s eye at 100 yards, lying with his back on the ground; and, notwithstanding the unequalness of the wind and wetness of the weather, he only missed the target three times during the whole course of the experiments.[16]

The demonstration had a dramatic effect. Lord Townsend, the Master General of Ordnance, directed that one hundred rifles should be produced and that Ferguson was to oversee their production. Four Birmingham gunmakers were contracted by the Board of Ordnance to produce twenty-five rifles each; these companies were William Grice, Benjamin Willetts, Mathias Barker (in partnership with John Whateley), and Samuel Galton & Son. Birmingham was then the hub of British gun manufacture; in 1788 it was estimated that some 4,000 gunmakers were at work in the area.[17] Each contractor was paid £100 for twenty-five guns, each rifle costing £4. Little is known about the production of the guns and the manufacturing techniques used but the screw plugs would have taken many hours of work using a treadle lathe and lapping techniques to fit them for each rifle.[18]

The rifles were handmade and as a result none of their parts were interchangeable. To ensure the unique breech plugs were matched to the right rifle, engraver William Sharp was paid three pence per rifle to engrave serial numbers in three places on the rifles: the butt plate, trigger guard and the tang.

Keen to experiment, Ferguson was given a small detachment of six men from the 25th Regiment of Foot to train in the use of his rifle and on October 1, he gave a demonstration for King George III at Windsor.[19] With his small detachment Ferguson repeated some of his earlier feats of marksmanship, firing from his back and putting five rounds into the bullseye.

During his meeting with the King, Ferguson also confidently proposed a new practical uniform for light troops. Sources do not confirm the color of these proposed uniforms, but Ferguson’s experimental corps did later have green jackets made up when they arrived in America.[20] This was not unusual; during the previous French & Indian War some British light infantry units including Rogers’ Rangers and Gage’s 80th Regiment of Light-Armed Foot had worn proto-camouflage uniforms just as did some of Ferguson’s contemporaries like the Queen’s Rangers and Tarleton’s British Legion.

As a result of his demonstrations and petitioning of senior officers Ferguson was authorized to raise an experimental corps of riflemen to test the rifle in the field, composed of 200 men formed into two companies.[21] This plan was temporarily cancelled in late 1776, but early the next year Ferguson was directed to begin forming and training a company of men at Chatham. The men who formed the new corps were drawn from the 6th and 14th Regiments of Foot, Ferguson and 100 riflemen were given orders to sail to sail for America on the March 11, 1777.[22] There they would join Gen. William Howe’s imminent campaign to take Philadelphia.With time short, Ferguson scrambled to gather supplies and begin training his men in the use of his rifle.

Captain Ferguson was formally seconded from the 70th Foot and officially given his command on March 6, 1777, his corps authorized for one campaign season after which Ferguson and his men would have to return to their units unless the experimental corps was seen as worthy of maintaining. Ferguson and his men arrived in New York in late May. Interestingly, according to Roberts and Brown’s book Every Insult & Indignity, Ferguson’s report to the Ordnance Store Keeper in New York noted that his corps arrived with only sixty-seven “rifle guns.”[23] Correspondence dating from June 1777 from the Master General of Ordnance’s secretary shows that a further thirty-three rifles were sent to America along with forty bayonets. It is unclear if these reached Ferguson and his men by the time they embarked for the Philadelphia campaign.[24]

Ferguson’s company took part in the fighting in New Jersey in June 1777 before General Howe withdrew his army from that region and regrouped to take a different approach to Philadelphia. In July, Ferguson confirmed that his “small command,” which had lost six men in early skirmishing, “never exceeded 90 under arms,” a far cry from the 160 to 200 he had hoped to field.[25] Ferguson realized that to grow his corps he would have to take men from other battalions, who were naturally averse to this. If Ferguson did not have enough rifles to equip his entire corps it seems likely that his men were armed with a mixture of rifles and standard issue muskets.

Throughout the Philadelphia campaign Ferguson’s experimental force acted as scouts and fought in a number skirmishes and engagements, the largest of these being the Battle of Brandywine. Ferguson and his company were attached to Gen. Wilhelm von Knyphausen’s column which was tasked with fixing George Washington’s Continental Army in place while General Howe’s main force flanked the American position. Ferguson and his men found themselves in some hot fighting at the head of Knyphausen’s column with the light infantry vanguard which screened the advance. Alongside the Loyalist light infantry battalion, the Queen’s Rangers led by Maj. James Wemyss, Ferguson’s riflemen pushed back American light infantry under Brig. Gen. William Maxwell.[26]

During the battle Ferguson and a party of his riflemen supposedly encountered George Washington, chivalrously deciding not to open fire. However, despite Ferguson’s own account of the encounter he could not confirm it was Washington and much myth surrounds the story. While the story cannot be proven with any degree of certainty it is definitely a colourful anecdote. Shortly after the alleged encounter Ferguson was badly wounded and his men were forced to fall back. He was shot in the right arm, his elbow shattered by a musket ball.[27] It took a year for Ferguson to recuperate, requiring numerous painful surgeries removing bone fragments to save his arm from amputation.

In the meantime, with well-trained light infantry in short supply, Ferguson’s experimental corps was disbanded. His men were returned to their original parent units and while one contemporary source suggest their rifles were placed in store, other evidence suggests the men took their kit back to their parent battalions.[28] Heavy casualties are often described as one of the key reasons for the rifle corps’ disbandment.[29] In reality Ferguson’s losses were comparatively minor. Wemyss’ Rangers suffered heavily, losing fourteen killed along with ten officers and forty-four other ranks wounded, while Ferguson’s corps suffered just two killed and six wounded—including Ferguson himself.[30] In a letter home to his brother George, Ferguson attributed this relatively low casualty rate to “the great advantage of the Arm [his rifle] that will admit of being loaded and fired on the ground without exposing the men.”[31]

Xavier della Gatta’s 1784 painting of the Battle of Paoli shows what is believed to be some of Ferguson’s men, in their green jackets with their long sword bayonets fixed, over a week after Brandywine.[32] De Witt Bailey also notes that a February 1778 entry in the orderly book of the Guards brigade calls for an inventory of the rifles still in use with various battalions.[33] If this was the case then attrition of the remaining guns from use in the field partially explains why so few survive today. In July 1778, an order was issued to the army for the return of all Ferguson rifles still in use to the Ordnance Office for repair and probably storage.[34]

Recovered but with a largely lame right arm, Ferguson returned to duty in late 1778, leading a number of scouting expeditions and raids on American bases at Chestnut Neck and Little Egg Harbour, in New Jersey.[35] He was subsequently made a brevet lieutenant colonel and appointed commanding officer of a Loyalist militia force, the Loyal American Volunteers, and later was made Inspector of Militia in the Carolinas.[36] During 1779 and 1780, Ferguson led his Loyalist volunteer forces in the Carolinas.[37] Interestingly, a Commissary of Artillery ordnance stores return from November 1779 to May 1781, found in the Sir Henry Clinton Papers, notes that 200 “serviceable” rifles were issued to a “Capt. Pat. Ferguson” on December 16, 1779.[38] It does not state whether any of these rifles were of his pattern or if they were all muzzleloaders. While commanding the Loyalist militia force Ferguson was killed during the Battle of Kings Mountain in South Carolina, in October 1780.[39]

Opinions of Ferguson from historians is somewhat divided. Andrew O’Shaughnessy describes him as an example of “ambition, motivation, professional dedication and courage.”[40] Ian Saberton describes Ferguson as “a humane, benevolent officer who, despite trying circumstances, applied his best endeavours.”[41] Wayne Lynch is more critical of his strategic skill, suggesting that despite being “an active and enthusiastic soldier, I do not see military genius . . . he was a probably a good officer at times but not really the stuff of independent command.”[42] Despite his debated ability as a soldier and tactician, Ferguson’s true legacy lies with his innovative rifle, his belief in his design and the limited but intriguing service it saw.

Ferguson’s Rifle

For the purposes of this article we will confine our discussion to the military-pattern Ferguson rifles, excluding later hunting pieces. There is a great deal of variation among the few surviving Ferguson Rifles, in terms of minor differences such as wood or steel ramrods or the type of rear sight, but also more fundamental differences such as the use of brass or bronze plugs or the number of breech screw threads and the presence and positioning of fouling grooves. This is the result not just of eighteenth-century manufacturing processes but also due to choices made by individual gunmakers and evolution of the design itself.

Typically, the surviving rifles have a number of common features including the multi-start breech plug, trigger guard lever, the presence of one of two unusual patterns of rear sight and a bayonet lug beneath the barrel. While there is some slight variation in barrel length and bore diameter, the style of stock seen on the rifles is fairly uniform. The Board of Ordnance rifles had .65 calibre bores and used the same eight-groove rifling as the Jaeger-pattern 1776 muzzle-loading rifles, not the four-groove rifling that Ferguson patented, presumably for ease of manufacture.

Markings on the rifles vary with the manufacturer. The guns made for the Board of Ordnance have marker’s stamps on the barrel, various proof markings and a serial number at the tang while the locks were marked with “Tower” and “GR.” The non-Board of Ordnance guns have commercial gunmaker’s marks on both lock and barrel. Most of the surviving military pattern rifles have wooden rather than steel ramrods. There is some slight variation in the brass pipes which hold the ramrod as well as some differences in the position and width of the bass nose cap. The ramrod could be used to muzzle-load the rifle if the screw plug became jammed or so fouled it could not be opened. Provided the plug was in place the rifle could still be loaded from the muzzle, but without the plug the rifle was useless.

Two patterns of rear sight are seen, the Board of Ordnance guns having a rear notch post sighted at 200 yards, a folding leaf sight with an aperture sighted at 300 yards, and a further notch cut above the aperture likely sighted for 350 yards. The other pattern of sight, not seen on the Ordnance contract guns, is a brass rear sight located behind the breech, just in front of the tang, which slides up and down. This sight is on two Durs Egg-made rifles as well as an example produced by Hunt dating from 1780 held by the National Army Museum.[43]

The two surviving rifles believed to be original Board of Ordnance guns, held at the Morristown National Historical Parkand the Milwaukee Public Museum, have eleven-thread breech plugs; other surviving rifles have ten.[44] Not all of the surviving Ferguson rifles appear to have the anti-fouling cuts described in the 1776 patent. The style of trigger guard varies with most being made from iron, but all appear to be held in the closed position by a similar detent projecting from the rifle’s wrist. Damage to the guns is common as the stocks proved to be somewhat fragile. The two of the surviving rifles believed to have been used by Ferguson’s experimental corps have a number of cracks and breaks in their stocks; whether these occurred during service or in the years afterwards is unknown but the wrists and wood surrounding the breech and lock are fragile.

Some of the improvements that Ferguson made to La Chaumette’s earlier system are discussed above. According to Ferguson’s patent the breech plug was designed to be cleaned without having to be fully removed from the rifle; the lower section of the plug on some guns was smooth and allowed fouling to be pushed out of the threads as the action was worked. The plug was not retained in the gun by any mechanical means, however, and if unscrewed too far could come free. Additionally, according to Ferguson’s patent, the threads cut into the plug directed fouling away from the breech and were intended to spread powder gases evenly.[45] A “hollow or reservoir” behind the plug also helped direct fouling out of the action; not all surviving examples have this. The chamber and ball had a larger diameter than the barrel to ensure the ball remained seated until fired and to make sure it engaged the barrel’s rifling.

Firing the Ferguson

The loading procedure prescribed by Ferguson for his rifle is uncertain as no instructions have survived. The rifle used the British Army’s standard .615 calibre carbine ball, rather than a full sized .71 musket ball. Like the British 1776 Jaeger-pattern rifles, Ferguson’s rifle used special double-strength or “double glazed” rifle powder. De Witt Bailey notes that five 100-pound barrels of this powder were ordered for Ferguson’s corps before they embarked for America, each barrel costing £7 and 10 shillings, roughly six times more expensive than regular issue powder.[46]

Riflemen likely carried both paper cartridges and a powder flask and ball bag. To load, the rifleman would first place the rifle on half cock (a safety position where the trigger cannot be pulled) and then unscrew the breech. He would then place a ball into the breech, where it was held in place by the narrower bore. Then he would pour in powder behind the ball either from his flask or from a cartridge, before screwing the breech plug back into place. He then primed his pan from either his flask, the remains of the cartridge, or by pushing excess powder from the top of the breech across into the pan. He was then ready to fire.

The Ferguson had the advantage of much quicker and easier loading than contemporary muzzle-loading rifles. A muzzle-loading rifle takes longer to load as the ball has to be forced down the rifled bore, mating it with the grooves, which becomes more difficult as the barrel fouls with black powder residue. The Ferguson also had the distinct advantage of allowing the rifleman to rapidly load and fire in almost any position, or even while on the move, enabling him to make best use of cover—a tactic favored by the light infantry.

The all-important question is, how good of a weapon was the Ferguson? The two greatest advantages of Ferguson’s design were the ease and speed with which it could be loaded, and its accuracy. While speed was not Ferguson’s primary focus his impressive demonstrations showed that it could be fired far more rapidly than a muzzle-loading musket. During the 1777 campaign, and specifically during the Battle of Brandywine Creek, Ferguson found that the weapon’s ability to be loaded from cover was a significant advantage. At just over thirty-two inches long the barrels of Ferguson’s 1776 rifles were ten inches shorter than the Short Land Pattern musket (today commonly called the Brown Bess) then in service. It was substantially lighter, weighing around 7.5 pounds to the musket’s 10.5 pounds.[47] This made the rifle a handier weapon, one ideal for use by light infantry. The Ferguson was also far more accurate than the Short Land Pattern muskets.[48] But while the rifle was light, accurate and reliable it did have several weaknesses.

The first weakness stemmed from its construction. The rifle’s slender, lightweight stock was prone to cracking at the lock mortice where the wood was thinnest. As a result an iron horseshoe-shaped repair beneath the lock surrounding the breech screw was added to the rifle held at the Morristown National Historic Park, but it is unclear when this reinforcement was added. While not as robust as a standard issue musket, it is important to remember that the first batch of Ferguson rifles were still prototypes and the design could have been improved.

The cost of the rifles was also a disadvantage, as they were markedly more expensive than a smoothbore musket or even the Jaeger-pattern muzzle-loading rifles, which were around seventeen shillings cheaper. The cost of producing one Ferguson Rifle during the first production run of one hundred was in £4, double the cost of the Short Land Pattern musket, although economies of scale may have made the rifle cheaper had it gone into large-scale production. This and the slower rate at which the rifle was able to be produced meant that it could not be produced in the numbers necessary to challenge the dominance of the musket as the primary light infantry weapon.

Only one hundred rifles were officially made for the army, and the fate of most of them is unknown. A handful of original Ferguson rifles survive in private and public collections. After his death some of London and Birmingham’s finest gunsmiths, including Egg, Henry Nock, and Joseph Hunt, made Ferguson-pattern rifles in relatively small numbers for both military and hunting purposes.

Ernie Cowan and Richard Keller, who have built replicas of the rifle, describe it as “one of the finest rifles built during the eighteenth century.”[49] But Bailey describes it as “virtually useless as a military weapon” because the weakness of the rifle’s stock and the potential for fouling of the breech and bore.[50] In these criticisms I believe Bailey is too harsh. It must be remembered that these were prototype rifles being used by an experimental corps; the strength of the rifle’s wooden furniture could have been improved relatively easily and the impact of fouling is debated by those who have experience with modern black powder replicas.

While some erroneously believe the rifle was destined to replace the Short Land Pattern musket in general service, this is not the case. The Master General of Ordnance had initially directed the future focus of rifle production should be on the Ferguson breech-loader rather than the Jaeger-pattern; however, if larger scale production had begun, the rifles would only have been destined for light troops, the elite, disciplined well-trained, skirmishers who were best suited to their use. Ferguson himself was a proponent of light infantry, even suggesting that half the army in America should be light infantry, but I do not believe he intended his rifle to be issued to every soldier.

Ferguson’s riflemen never really had the chance to make the impact their commander desired. Sir William Howe made no mention of him or his men during his official report on the Battle of Brandywine.[51] The experimental corps was simply too small to do anything more than prove their concept. By the late 1770s the conventional British light infantry were more than a match for their American counterparts. Ferguson himself wrote Gen. Clinton in August 1778, noting that British light troops had gained “that superiority in the woods over the rebels which they once claimed.”[52]

The Ferguson Rifle has the distinction of being the first breech-loading rifle adopted for service by the British Army. Its service life, however, was short, especially compared to the 1,000 Board of Ordnance 1776 Jaeger-pattern rifles used throughout the war. Sadly, with so few made and with the wounding and later death of its inventor, the rifle did not have the opportunity to fully prove itself. It would be another twenty-two years, during the Napoleonic Wars, before the British Army experimented with a green-coated, rifle-armed unit again—what would become the 95th Rifles.

[1]Marianne M. Gilchrist, Patrick Ferguson ‘A Man of Some Genius’ (Edinburgh: NMS Enterprises Limited, 2003), 5.

[2]Matthew H. Spring, With Zeal and With Bayonets Only: The British Army on Campaign in North America, 1775-1783 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010 ), 246-8.

[4]“Flintlock breech-loading rifle – By John Hirst (about 1760),” Royal Armouries, collections.royalarmouries.org/object/rac-object-361.html, accessed November 3, 2018.

[5]Howard L. Blackmore, British Military Firearms 1650-1850 (Huntingtdon: Ken Trotman Publishing, 2010), 72.

[6]“Flintlock breech-loading gun (1727),”Royal Armouries, collections.royalarmouries.org/object/rac-object-15502.html, accessed November 3, 2018.

[7]Discussed in William Keith Neal, “The Ferguson Rifle and its Origins”, American Society of Arms Collectors, Bulletin #24 (Fall, 1971), and De Witt Bailey, British Military Flintlock Rifles 1740-1840 (Lincoln: Andrew Mowbray, 2002), 35.

[8]Gilchrist, Patrick Ferguson, 25.

[9]Jared Sparks, ed., Correspondence of the American Revolution Vol. II (Ithaca: Cornell University Library, 2009), 501-502.

[10]Bailey, British Military Flintlock Rifles, 26-29.

[11]The Scots Magazine, Vol. 38, 1776, 217, books.google.co.uk/books?id=ft4RAAAAYAAJ&dq=%27Captain+Patrick+Ferguson%27+the+king&q=ferguson#v=snippet&q=rifle&f=false, accessed October28, 2018.

[13]Bailey, British Military Flintlock Rifles, 37.

[14]Quoted in Bryan Brown and Ricky Roberts, Every Insult and Indignity: The Life Genius and Legacy of Major Patrick Ferguson, (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform 2011), Chap. 3 Kindle.

[15]The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle,Vol.41, 1776, 575, books.google.co.uk/books?id=cL9NAAAAcAAJ&dq=he+fired+during+four+or+five+minute+at+a+target%2C+at+200+yards+distance%2C+at+the+rate+of+four+shots+each+minute.&q=ferguson#v=snippet&q=ferguson&f=false, accessed October 30, 2018

[16]The Annual Register, or a View of the History, Politics and Literature for the Year 1776, 148, books.google.co.uk/books?id=JJI-AAAAYAAJ&pg=RA1-PA148&lpg=RA1-PA148&dq=he+fired+during+four+or+five+minute+at+a+target,+at+200+yards+distance&source=bl&ots=KKUtd0ASaK&sig=Ea0az8UUxbhYUzPTzuXg25LPzWo&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwio_NvlvObdAhVKDMAKHQl7CM4Q6AEwCnoECAoQAQ#v=onepage&q=he%20fired%20during%20four%20or%20five%20minute%20at%20a%20target%2C%20at%20200%20yards%20distance&f=false, accessed September 28, 2018.

[17]David Williams, The Birmingham Gun Trade (Stroud: The History Press, 2009), 37.

[18]Richard Keller and Ernest Cowan, “Shooting the Military Ferguson Rifle,” British Military Flintlock Rifles, edited by Bailey, 219-221

[19]The London Magazine, Or, Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer, Vol.45, 1776, 557,

books.google.co.uk/books?id=DfgRAAAAYAAJ&dq=american+riflemen&q=riflemen#v=snippet&q=riflemen&f=false, accessed October 18, 2018,

[20]Gilchrist, Patrick Ferguson, 29.

[22]The Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol.47, 1777, 144, books.google.co.uk/books?id=bHfPAAAAMAAJ&dq=he+fired+during+four+or+five+minute+at+a+target%2C+at+200+yards+distance%2C+at+the+rate+of+four+shots+each+minute.&q=ferguson#v=snippet&q=riflemen&f=false, accessed October 24, 2018.

[23]Roberts & Brown, Every Insult and Indignity, Chap. 11, Kindle.

[24]Bailey, British Military Flintlock Rifles, 44.

[25]Gilchrist, Patrick Ferguson, 37.

[26]Michael C. Harris, Brandywine: A Military History of the Battle that Lost Philadelphia but Saved America, September 11, 1777 (El Dorado Hills: Savas Beatie, 2014), 223-238.

[27]The Scots Magazine, Vol.39, January 1777, 603, books.google.co.uk/books?id=F14AAAAAYAAJ&dq=%27Captain+Patrick+Ferguson%27+the+king&q=ferguson#v=snippet&q=ferguson&f=false, accessed October 29, 2018

[28]Bailey, British Military Flintlock Rifles, 54.

[29]Blackmoore, British Military Firearms, 85.

[30]The Westminster Magazineor the Pantheon of Taste for June, 1777, Vol.5, Issue 2, 645, books.google.co.uk/books?id=NAQwAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA645&dq=Ferguson%27s+corps+of+riflemen&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj4vrSXv4zeAhUKLMAKHf6bA58Q6AEIPDAE#v=onepage&q=Ferguson’s%20corps%20of%20riflemen&f=false, accessed October 27, 2018.

[31]Gilchrist, Patrick Ferguson, 39-40.

[32]S.R. Gilbert, “An Analysis of the Xavier della Gatta Paintings of the Battles of Paoli and Germantown, 1777: Part 1,” The Military Collector & Historian, 46, (1994), 98-108.

[33]“Orderly Book of Composite Guards Brigade, 21 Feb. 1778,” William L. Clements Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan, quoted in Bailey, British Military Flintlock Rifles, 54.

[34]Bailey, British Military Flintlock Rifles, 54.

[35]The London Gazette, November 28, 1778, Issue: 11931, 2,www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/11931/page/2, accessed November 2, 2018.

[36]The Scots Magazine, Vol.42, 1780, 425, books.google.co.uk/books?id=uV4AAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA425&dq=Ferguson+71+major&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjjrfbbwozeAhVNasAKHUS1BIUQ6AEIKTAA#v=onepage&q=Ferguson%2071%20major&f=false, accessed November 6, 2018.

[37]“Col. Ferguson’s defeat,” The Scots Magazine, Vol.42, 1780, 688, books.google.co.uk/books?id=wEc2AAAAMAAJ&dq=%27Captain+Patrick+Ferguson%27+the+king&q=ferguson#v=snippet&q=ferguson&f=false, accessed November 3.

[38]“Return of Small Arms in Ordnance Stores, New York, Nov. 30, 1779—May 8, 1781,” Sir Henry Clinton Papers 155: 7, W. L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[39]The Scots Magazine, Vol.32, 1780, 29, books.google.co.uk/books?id=lOERAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA29&dq=scots+magazine+captain+patrick+ferguson++king&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiuutvo1ubdAhVkK8AKHZd_DUsQ6AEIKTAA#v=onepage&q=scots%20magazine%20captain%20patrick%20ferguson%20%20king&f=false, accessed November 6, 2018.

[40]Andrew O’Shaughnessy, The Men Who Lost America (London: Oneworld Publications 2013), 263.

[41]Ian Saberton “The Revolutionary War in the South: Re-Evaluations of Certain British & British American Actors,” Journal of The American Revolution, allthingsliberty.com/2016/11/revolutionary-war-south-re-evaluations-certain-british-british-american-actors/,accessed October20, 2018,

[42]Wayne Lynch, “A Fresh Look at Major Patrick Ferguson,” Journal of The American Revolution, allthingsliberty.com/2017/09/fresh-look-major-patrick-ferguson/,accessed October 17, 2018.

[43]“Ferguson flintlock breech-loading rifle, 1780,” National Army Museum, collection.nam.ac.uk/detail.php?acc=1976-11-74-1, accessed November 2, 2018.

[44]“Ferguson Rifle,” American Revolutionary War Morristown National Historical Park, www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/revwar/image_gal/morrimg/fergusonmusket.html, accessed October 12, 2018; and “Ferguson Breech Loading Rifle,” Milwaukee Public Museum,www.mpm.edu/node/27076, accessed October 12, 2018.

[45]Patrick Ferguson, Patent No. 1139 December 2, 1776, UK National Archives.

[46]Bailey, British Military Flintlock Rifles, 43.

[48]De Witt Bailey, “British Military Small Arms In North America 1755-1783,” American Society of Arms Collectors, Bulletin #71 (Fall, 1994),

americansocietyofarmscollectors.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/British-military-small-arms-in-North-America-1755-to-1783-B071_Bailey.pdf, accessed October 20, 2018

[49]Bailey, British Military Flintlock Rifles, 219.

[51]The Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol.47, 1777, books.google.co.uk/books?id=bHfPAAAAMAAJ&dq=he+fired+during+four+or+five+minute+at+a+target%2C+at+200+yards+distance%2C+at+the+rate+of+four+shots+each+minute.&q=brandy#v=snippet&q=brandywine&f=false, accessed October 21, 2018.

[52]Howard Peckham, ed., Sources of American Independence (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1978), 2307.

13 Comments

The July 30, 1970 Index-Journal Newspaper from Greenwood, SC tells of an original Ferguson rifle stolen from the Kings Moutain National Park. It says the rifle was stolen in April of 1969. Says the park bought the rifle from a family in Scotland and the FBI was investigating the case. I couldn’t find if the rifle was ever found.

When stolen it was believed the rifle never left the state. I was the historian at Kings Mountain National Military Park from, I believe, 1970-1972. Years after my time the Ferguson Rifle was recovered in South Carolina and later put on display which was my good fortune to view many, many years later. Enjoyed the article.

William E. Cox

Fascinating read! But what really caught my attention was the fact that a bayonet could be mounted on the rifle. Something which I haven’t known before! I’m also curious about how the article says that Gatta’s 1784 painting “shows what is believed to be” some of Ferguson’s men with sword bayonets fixed to their rifles. Very Interesting, as I haven’t read about sword bayonets prior to the Baker Rifles made famous by the 95th.

Could you provide more context on the Ferguson sword bayonets? I’ve read the hyperlinked article “The First Fight of Ferguson’s Rifle” which stated that the bayonet was 25 inches long and 1 1/2 inches wide “and being of fine temper and razor edge was called a sword bayonet.” I’m wondering if this would have been a “true” sword bayonet like that of the Baker Rifle. All in all I’m just wondering how the Ferguson sword bayonet would have looked like, and if there’s any other historical depictions (or even surviving examples) of any.

I don’t believe any survive, from Gatta’s painting its suggested they had an almost cutlass like blade to them rather than straight like the later baker rifles. They are said to have been of Ferguson’s own design and numbered to the rifles.

The Ferguson sword bayonet was a socket bayonet with the flat blade slung UNDER the barrel instead of BESIDE it as in normal muskets. The flat of the blade was parallel with the ground, unlike the long sword bayonets occasionally used with Brown Besses whose flat blades were perpendicular to the ground when the gun was shouldered. The long Ferguson blades made the rifle plus bayonet similar in length to the Bronze Bess plus bayonet. The Ferguson bayonet was an off-shoot of an earlier French sword bayonet of similar shape, but shorter.

The only original example I am aware of is with the DePeyster Ferguson rifle in the Smithsonian, and which was Ferguson’s personal rifle given to DePeyster after the Brandywine battle.

Copies were made for Rifle Shoppe Ferguson kits, and by Ernie Cowan, who made the best bench copies of the ordnance Fergusons.

I recently acquired an original Ferguson sword bayonet in an auction in the north of England. Fortunately for me there was an internet lag which snookered the online bidders plus the auction house were unaware of what they had – the two socket bayonets in the lot comprised of a very nice early Brown Bess in scabbard ‘plus one other….’ The bayonet now resides in my sockets drawer amongst other ‘Holy Grails’.

Outstanding article on a subject about which I’ve been long curious! However, please clarify the last sentence in the first paragraph: “In an age when three or four rounds a minute from a trained infantryman was regarded as an impressive standard, six, or even seven, accurate shots a minute had the potential to be tactically ground breaking.” As I outline on my “Charleville Musket Firing” webpage, 3-4 rounds per minute was an average for a musket. 1 round per minute was an average for a rifle. I presume the author’s “trained infantryman” refers to a musket bearer, and the “accurate shots” refers to a rifleman. Just want to be sure. Thanks for clarification. Again, great article! BTW, I’ve added a link to your article on my webpage.

Hi William, very glad you enjoyed the article. Ahh yes indeed I did mean that 3 to 4 would be the standard of a well trained infantryman with a musket. Thanks for reading!

Excellent, informative piece, Matthew. Do you happen to know whether any La Chaumette rifles are in existence? Also, aficionados in the Mid-Atlantic region may be interested to know that what is identified as a Durs Egg officer’s Ferguson is on display at the Washington Crossing museum on the New Jersey side.

Thank you! Yes there are some still in existence. There are several in collections in Europe. There’s some older photos of them on the UK’s Royal Armouries’ online catalogue which can be searched. One given to King George II or possibly III.

Hello Matthew:

You have produced a very good and balanced piece; one of the best on this topic. The della Gatta gouache of Paoli was indeed produced in 1782, not 1784.

Any analysis of the value and impact of the Ferguson Rifle is incomplete until an evaluation of the troops using it is completed. Ferguson’s Rifle Company is an elusive body of men to research and precious little appears to have been done along this line. It seems to have been badly understaffed with officers and supplied with minimally experienced replacement men destined for other regiments. A standard 100-man large company ought to have had a captain and three lieutenants. We know of only Ferguson and Lieutenant John DeLancey, seconded from the 18th Foot. There ought to have been two more and yet nothing appears in contemporary records. Gentlemen Volunteers, however, might have been a temporary solution.

Frustratingly, the Rifle Company lost both their officers the day after Brandywine; Ferguson to wounds and Delancey to promotion within the Loyalist corps. Yet someone had to be keeping track of company pay, discipline, daily orders, etc. Howe’s Army was in the middle of enemy territory and in no position to receive fresh reinforcements except from within its own ranks. The obvious solution was to cannibalize the experimental group of riflemen. Army orders show large numbers of Gentlemen Volunteers were promoted to Ensigncies immediately after Brandywine, and some of these could have been previously useful to Ferguson. In short, Ferguson’s company started to shrink the moment its officer corps dwindled.

My analysis of the della Gatta paintings specifies the officer of the 2nd Light Infantry who was seconded to the temporary rifle company within the battalion; they took the lead in the Paoli attack with the 52nd LI company directly behind. Those green-coated men in della Gatta’s “Paoli” have long bayonets protruding down below the barrels; only a Ferguson rifle has that appearance.

The War Office Papers, WO12 Company Pay Rolls contain entries for “Rifflemen” and “Farguson’s” replacement men among individual light infantry Companies in both Light Infantry battalions and for battalions companies within Howe’s Army starting 12 September and running through 24 October. Your observation that Ferguson’s company simultaneously had both rifles and muskets in action seems to be borne out by these entries. Not all records are complete and much needs to be re-studied, but specifically-named Ferguson’s men were sent to the 4th, 17th, 38th, 43rd, 52nd, 57th Light Infantry companies. Additional British replacement men, who could not have possibly been sent from New York or Great Britain due to the Delaware River’s closure appear during October in various army-wide battalion companies. I suspect those are convalesced Ferguson men.

I am glad you left the Ferguson-could-have-shot Washington story alone. It cannot be proved with ANY degree of accuracy, and to swallow it one must believe that on the eve of the biggest battle of his life, Washington abandoned his own headquarters (where he was anxiously awaiting incoming messages from subordinates about the location of a huge detachment of Howe’s army). He then ventured far beyond his army’s lines in company with a single foreign horseman and rendered himself hors du combat. It doesn’t pass the smell test from the start.

Best regards,

Stephen Gilbert

Hi Stephen,

Thank you for the kind words. I agree much needs to be readdressed and reexamined! I think gentlemen volunteers is a very good theory, perhaps some loyalist young men joined at New York. In which case Ferguson’s Corps must have been exceedingly green – pardon the pun, with the inexperience of his men and only one other experienced officer on hand to lead them, this may explain why Ferguson was at the head of his men and exposed to fire at Brandywine (of course as a company commander he wouldn’t have been removed from action). My apologies for the typo in the della Gatta date!

I’m glad your research supports the theory that they were sent either back to their units or wherever they were most needed. I completely agree with you on the Washington myth. It seems highly implausible and I would have preferred to not mention it at all but better to discount it than perpetuate it!

Thanks again for the comments.

Back in the 1980’s while searching a trash pit in a British camp in the New York city area I recovered a severely corroded iron trigger guard to a Ferguson Rifle. Dr Bailey flew in from England to examine it and concluded it was one of the original 100. Unfortunately corrosion prevented any legible numbers to survive. On page 54 of Dr Bailey’s British Military Flintlock Rifles, a picture illustrates the find in comparison to the Morristown example.