The British army that Lt. Gen. John Burgoyne surrendered to the American army at Saratoga, New York on October 17, 1777, was first marched to Cambridge, Massachusetts and lodged in barracks. The British component was relocated to Rutland, Massachusetts in 1778, while the German component remained in Cambridge. For several reasons, including concern that a British raid would liberate these prisoners, the Continental Congress decided in the fall of 1778 to move the Convention Army (as it was called after its mode of surrender) to a location farther from the coast and selected Charlottesville, Virginia. That army marched from Massachusetts on November 9 thru 11, 1778 and arrived at Charlottesville in January 1779, to find an unfinished set of barracks awaiting them.[1]

The Continental Congress decided on Charlottesville on October 16, 1778 and instructed the Board of War to contract for building “temporary log barracks” near the town and completing them by December 15.[2] The board acted with dispatch to award a contract for construction of the barracks to Capt. George Rice, a former Continental soldier from Virginia who had transferred to the Quartermaster General’s Department, on land northwest of Charlottesville owned by Col. John Harvie, a member of the Continental Congress.[3] Since Rice had to provide quarters for approximately 4,000 soldiers in a rural location with a limited local workforce and insufficient time, it is not surprising that the Convention Army found its barracks in an unfinished condition. The men immediately began sealing and finishing the huts to improve their habitability.[4]

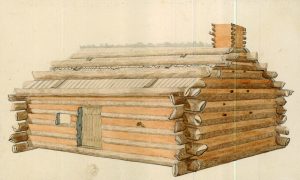

These facilities (the “Albemarle Barracks”) were described by several members of the Convention Army, with certain inconsistencies, as having comprised about 300 individual log huts built in blocks containing four twelve-hut rows in which the huts were closely-spaced. Each hut was approximately twenty-four feet long by fourteen feet wide and was reputed to hold up to eighteen men.[5]

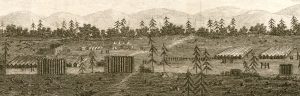

Seven of these blocks of huts were constructed with a “main street” separating the blocks occupied by the British troops from those occupied by the Germans.[6] A contemporary rendering of a portion of the Convention Army campsite, while perhaps inaccurate in several instances, seems to capture this description for four of the seven blocks.[7] The significance of the separation between blocks will appear below in the report on the fate of the Albemarle Barracks.

The Convention Army occupied the Albemarle Barracks from January 1779 until new concerns arose about prisoner liberation caused by a British invasion of coastal Virginia in the fall of 1780. The British Convention troops were marched from Albemarle County on November 20, 1780, to Fort Frederick, Maryland while the German troops remained until February 20, 1781, when they were marched to Winchester, Virginia.[8] Various Continental enterprises were carried forth at the site of the Albemarle Barracks, possibly in some of the ancillary structures that were part of the camp and its garrison, throughout 1781.[9] Although the site contained many buildings at that time, all above-ground traces of them have vanished today.[10] In recent years the nature of their demise has been the subject of speculation, aided by a few clues, though it is described in a period report to the Quartermaster General.[11]

Following the departure of the German troops, Colonel Harvie enquired of the Continental Army’s quartermaster general, Timothy Pickering, concerning approval for the sale of “the Albemarle Barracks.” Pickering instructed Maj. Richard Claiborne, his assistant quartermaster general for Virginia, to commission a report of their condition prior to deciding how to proceed.[12] Claiborne in turn instructed the same Capt. George Rice who had been responsible for their construction, and was now his deputy assistant quartermaster, to inspect them and provide a report on his findings. Rice inspected the premises accompanied by local citizens John Henderson, Jr. and William Tandy, who concurred with his findings, and submitted his report to Major Claiborne on December 13, 1781, as follows:

Agreeable to your instructions I have made as exact inspection of the barracks and other public buildings at this place as seems to be required, & do report that all the ranges that were built for the use of the Convention Army cannot be considered in any other light than a pile of ruins, more than one third of them were burnt by the prisoners at the time they were ordered to Maryland, & the doors & windows of the others, I believe, almost without one exception, pulled to pieces & destroyed for the few nails that were in them. The taking off the facings from the doors & windows, which before confined the logs, has occasioned the huts in some instances, to tumble down, & in others to be greatly racked from their original shape. What plank was in them for floors or births [sic] has been entirely taken away; their covers are also, speaking generally, quite dismantled, the slabs that were on them being chiefly consumed or carried off by the Country people who seemed to consider every think [sic] of this kind, when the troops were removed, as free plunder, such few covers as remained have since the arrival of Armands legion at Charlottesville been taken down to that place to build stables for his horses.[13] In short, I cannot give you a description of these huts exceeding their present dismal condition. In addition to this, the Timber anyways contiguous to their buildings, was, during the stay of the Convention Army, used, for a great distance around the place, wherefore slabs or plank could now only be procured at a very heavy expence, therefore an attempt to repair such huts as now remain, would be attended with much heavier expence than to originate new ones in a well timbered wood. There condition at this time for quartering troops is in every respect as insufficient as if no such huts had ever been here if possible. The fate of the store houses & other buildings for the guard over the prisoners (having had more nails in them & other articles of pillage) has been severer than that of the Barracks above-mentioned except two of the officers houses of about twenty four feet in length & eighteen feet in width, covered & floored with rough plank, which are for the kind still in tolerable repair. These are on Col. Harvie’s land. Some Convention Officers houses that are inhabitable, but these were built at their own expence, by permission of Col. Harvie, therefore the Continent has no kind of interest or property in them. The logs of which these huts were built having been of green timber, with the bark on, they must of course soon rot, as they are, by loosing [sic] their roofs, quite exposed to the weather, they are besides, by being built in a regular form near each other much subject to fire which if it shou’d take in a windy day wou’d probably lay the greatest part of them in ashes, & I hardly presume the continent will think them of sufficient consequence to keep in pay, a guard to prevent such an accident. I do not know how to be more minute as your own observation when you rode through these Barracks must have shewn them to you in a state little superior to what they will now appear upon my representation.[14]

Claiborne forwarded the report to the quartermaster general who, on February 16, 1782, authorized him to “sell the [huts].”[15] No record of that transaction has been found though according to the report there remained little of value to be sold. No doubt Colonel Harvie was pleased to again have access to his land; perhaps he purchased the remaining material to accelerate the attainment of those circumstances.

The report provides a graphic description of the demise of the Albemarle Barracks: The British troops set fire to their huts when they departed, accounting for one-third, and the balance of the huts were plundered for building materials and left to collapse and rot.[16] Since they had deteriorated significantly by the end of 1781, and there was no reason to rebuild them even if that had been practical, it is unlikely the remaining material survived very long. Albemarle Barracks, locally called simply “the Barracks,” soon became the name only for the land on which the huts had stood.[17]

[1]Philander D. Chase, “’Years of Hardships and Revelations’: The Convention Army at the Albemarle Barracks, 1779-1781,” Magazine of Albemarle County History(MACH)41 (Charlottesville: Albemarle County Historical Society, 1983), 12-19.

[2]Journals of the Continental Congress12: 1016, 1018, Library of Congress, American Memory website, memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampageaccessed March 27, 2018.

[3]Richard Peters to Henry Laurens, October 20, 1778, Continental Congress Papers/Reports of the Board of War/1777-1779, 2: 343, fold3.com, accessed April 2, 2018; F.B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution, April, 1775, to December, 1783(Washington: W.H. Lowdermilk & Co., 1893), 345; Journals of the Continental Congress, 13: 39.

[4]Chase, “Years of Hardships and Revelations,” 19-20. The Convention Army marched from Massachusetts with 4,145 officers and men but arrived in Albemarle County with 3,750.

[5]August Wilhelm Du Roi, Journal of Du Roi the Elder, lieutenant and adjutant, in the service of the Duke of Brunswick, 1776-1778, Charlotte S.J. Epping, trans. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1911), 151; Schueler von Senden, “Excerpts from the Schueler von Senden Journal; 30 December 1778 through 21 November 1780,” MACH41: 125. The former describes the groupings of huts as squares, though they were rectangles, so “blocks” seems more appropriate. The latter stated, “each hut measures about 16 feet in square” but includes the sketch shown in the text which clearly indicates a rectangular configuration.

[6]J.A. Houlding and G. Kenneth Yates, “Corporal Fox’s Memoir of Service, 1766-1783: Quebec, Saratoga, and the Convention Army,” Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research48, No. 275 (Chelsea, UK: The National Army Museum, 1990), 163. Fox stated there were six men to each hut rather than eighteen; based on the size of the Convention Army when it arrived in Albemarle County, the average number per hut was about twelve.

[7]Thomas Anburey, Travels through the Interior Parts of America in a Series of Letters by an Officer2 (London: William Lane, 1789), 442; R.T. Huntington, “The Convention Army Camp Site in Retrospect,” MACH41: 4.

[8]Thomas Jefferson to George Washington, November 26, 1780, and James Wood to Thomas Jefferson, February 20, 1781, Founders Online, accessed April 3, 2018.

[9]Jefferson to Richard Claiborne, February 3, 1781, and William Davies to Washington, September 19, 1781, Founders Online, accessed April 3, 2018; William P. Palmer, Calendar of Virginia State Papers, 3 (Richmond: James E. Goode, 1883), 160, 180. These describe gun repair and the making of clothing, shoes and harnesses at the Albemarle Barracks location.

[10]Mary Rawlings, Ante-bellum Albemarle, Albemarle County, Virginia (Charlottesville: The Peoples National Bank, 1935), 44; Huntington, “The Convention Army Camp Site,” 4-6; Richard Mattson, Frances Alexander, Daniel Cassedy and Geoffrey Henry, From the Monacans to Monticello and Beyond: Prehistoric and Historic Contexts for Albemarle County, Virginia(Raleigh: Garrow & Associates, Inc., 1995), 52.

[11]Chase, “Years of Hardships and Revelations,” 44; Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Julian P. Boyd, ed., Vol. 6 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 631-633.

[12]John Harvie to Timothy Pickering, December 23, 1781, Miscellaneous Numbered Record No. 25075, U.S. Revolutionary War Miscellaneous Records (Manuscript File), 1775-1790s, Records Pertaining to Continental Army Staff Departments, Record Group 93, National Archives Publication M859 (MNR), Ancestry.com on August 5, 2017.

[13]Armand’s Legion arrived in Charlottesville between November 1 and November 22, 1781. See Washington to Charles, Marquis de La Rouerie Armand Tuffin, November 1, 1781, Founders Online, accessed March 27, 2018, and William P. Palmer, Calendar of Virginia State Papers, 2 (Richmond: James E. Goode, 1881), 617.

[14]George Rice to Richard Claiborne, December 13, 1781, MNR No. 25555. This document was marked received by Timothy Pickering on February 17, 1782 which is apparently incorrect based on the date of Pickering’s response to Claiborne. The visit of Claiborne to the Albemarle Barracks, mentioned in the last sentence of the report, took place in early July 1781 based on Palmer, Calendar of Virginia State Papers, 2: 202, 210, 217, 228.

[15]Pickering to Claiborne, February 16, 1782, Numbered Record Book 83, Records Relating to Supplies and Stores, Record Group 93, National Archives Publication M853, 96, Fold3.com, accessed August 5, 2017. A similar letter from Pickering to Harvie is on the previous page.

[16]Apparently, the distance between blocks of British and German huts prevented the latter from burning when the British set their huts on fire.

[17]Nathaniel Mason Pawlett, Albemarle County, Virginia Road Orders 1783-1816(Charlottesville: Virginia Highway & Transportation Research Council, 1975), 59, 109, 179, 225; Rev. Edgar Woods, Albemarle County in Virginia(Harrisonburg, Virginia: C.J. Carrier Company, 1978), 31.

3 Comments

I found the article, Demise of the Albemarle Barracks: A Report To The Quartermaster General was fascinating.

You brought to life a part of Albemarle history of which few locals are aware. The area is now the site of a golf course and shopping center. The enormous task of moving 4,000 enemy troops and the logistics of quickly establishing the Albemarle Barracks Camp was astonishing. As a professional genealogist in the Charlottesville area, I particularly enjoyed the detail and effort you put into your descriptive and interesting report.

It makes me think there must be more than a few iron nails waiting to be uncovered on Colonel Harvie’s land!

My 4th great grandfather, Heinrich Fogus/Voges, a German soldier was sent there as a prisoner and later deserted and went to Staunton, Augusta county. I would like to know more if possible.

James,

There are two research approaches you could take learn more about your ancestor: (1) the extensive body of literature on the Convention Army (which my article does not mention since I began it with that army’s move to Albemarle County) and (2) the records of Augusta County, Virginia. A cursory look at the latter shows that he is mentioned in them.

Bill