Since writing several articles for this journal about the role of Pennsylvania’s militia in America’s War for Independence, I’ve received a lot of confused inquiries about the organization of the militia because, well, it’s a confusing subject. I’ve also seen a lot of people who are searching for revolutionary ancestors get a lot wrong about the militia. In part this is because of the insane way militia is portrayed in popular culture (I’m looking at you Mel Gibson); of course it also doesn’t help that the militia in Pennsylvania were decidedly different than in other Colonies. In this article I’m just going to break down and explain Pennsylvania’s Militia system from the start of the war to the end of the war and hope that I don’t lose my mind trying to explain it all, because it’s complicated.

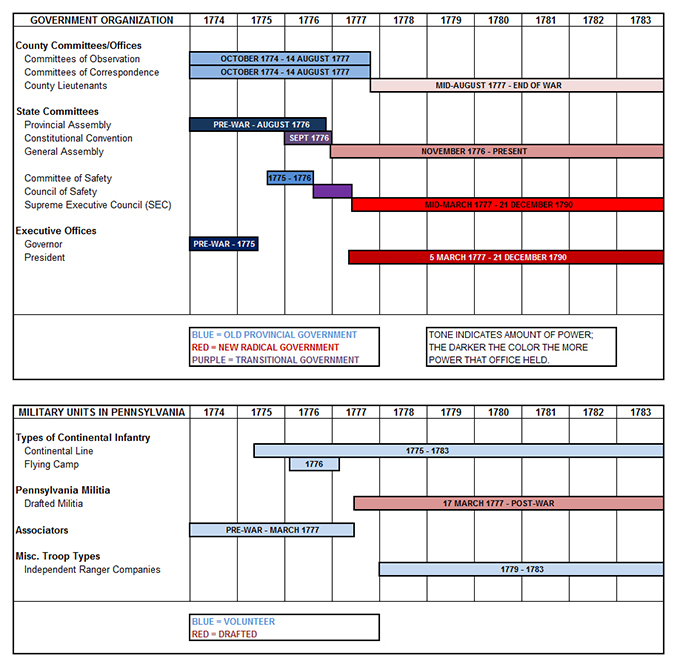

Pennsylvania had two major shifts in government during the war, and also major changes in the types of militia forces that defended the home front.[1] The shifts in government were actually instigated by the militia, and so they also dramatically impacted the militia system, besides profoundly upsetting the population. But don’t worry; I’ll explain this all in more detail because it is all interconnected. To better express this, here is set of charts:[2]

The first shift was the establishment of the ‘old revolutionary (or provincial) government’. Between June and November of 1774, counties throughout Pennsylvania saw the rise of patriot Committees of Correspondence, made up of local activist community leaders.[3] Depending upon where you lived, the means of forming this government could be violent and instant or slow and gradual.[4] While meeting only briefly in 1774, they began to meet more frequently through the early months of 1775, and then steadily after the start of the war.

While extralegal, these Committees worked closely with the Continental Congress and occasionally the Provincial Assembly (basically a House of Representatives). The state government itself remained essentially the same throughout this transitional period; the Provincial Assembly, under the control of Quakers, Mennonites, and other pacifists, supported the Continental Congress despite remaining against any military action. The governor of Pennsylvania held authority until war broke out in 1775; he was quietly asked to remove himself from power. In place of the governor, the Provincial Assembly, at the behest of the Continental Congress, put in place a Committee of Safety as many feared that without some semblance of authority over military matters, they would be at risk. To be clear, this first shift was not limited to Pennsylvania, but rather was happening throughout Colonial America in one manner or another.

Pennsylvania did not have permanent Militia Laws in place like other surrounding Colonies. In times of crisis—like an invasion, or threat of invasion—they would enact temporary laws that would expire after a certain time, but one would have better luck herding cats in a pet store full of birds than finding any semblance of a proper defense force in Pennsylvania. For example, it took the deaths of 200 settlers, the burning of over 50 homesteads, the complete desertion of the frontier, and countless petitions from sundry melancholy inhabitants for the Provincial Assembly to pass a temporary Militia Law in 1755, during the height of the French and Indian invasion.[5]

Primarily out of frustration over the Provincial Assembly’s stagnancy on the issue of defense, Benjamin Franklin founded the Philadelphia Military Association in 1747, modeled after London’s Military Association. These Associators were entirely volunteers; men could come and go as they pleased, and had to provide themselves with equipment. Over time, Military Associations sprang up in a handful of counties around Philadelphia. These Associators worked along with state-sanctioned militia following the enactment of the temporary Militia Laws.[6]

That raises an issue too; what were the Associators if not militia?[7] When they were initially formed, Associators did not necessarily owe allegiance to the Provincial Government or to the Colony of Pennsylvania (later the Commonwealth). Instead they all agreed to the Articles of the Association, and were obliged to sign a Form of Association (containing the list of Articles). The Provincial Assembly felt they had some minor control over them, but not really. The Associators could march when they pleased to wherever they pleased, and were not subjected to “any Pecuniary Mulcts, Fines, or Corporal Penalties, on any Account whatever; We being determined, in this whole Affair, to act only on Principles of Reason, Duty and Honour.”[8] While the state commissioned the officers, all officers were elected by the Associators themselves, thus preventing any officer from being appointed who might otherwise act against the interest of the Association. The relationship, needless to say, was a strained one.

These Associations went dormant after the French and Indian War until 1775, when news of Lexington and Concord found its way into the hands of local Committees. On 6 May 1775, the Northampton County Committee of Correspondence ordered that every township in the county should Associate and form into companies, equip and arm themselves, and prepare accordingly. Sixteen days later, the Committee met again and resolved:[9]

That the Association for our mutual preservation and Security now forming in this County be earnestly recommended to all the Freemen therein, and that they provide themselves immediately with all necessary Arms & Ammunition, and Muster as often as possible to make themselves expert in the Military Art.

By October, a count of all men in the county had yielded a large number of Associators: roughly 2,357 men from 26 townships had mustered. These results were typical for most Counties, with few exceptions,[10] but represented a small percentage of the state’s population as these were primarily more radical opponents of the Crown.[11]

The rise of Associations pressed the Continental Congress to place them under the Committee of Safety, who then organized a new set of Articles of Association. While broadly defined, these new Articles gave the Committee of Safety more control over the Associations, mainly through the commissioning of officers. In the Commission Form established by the Committee of Safety, they made clear that, through a common goal, they “do earnestly recommend to all Officers and Soldiers under your command to be obedient to your orders.”[12] These broadly defined powers, in the form of “recommendations,” made it clear that these were not under the authority of the state, but more directly the Committee of Safety, under the arm of the Continental Congress.[13] Perhaps the best analogy for this type of soldier would be the United States Volunteer regiments of the Civil War; they weren’t quite “regular” infantry, as the Continental Line, but they also weren’t militia.[14]

By 1776, Congress called for more troops to be raised to form a Flying Camp. The Flying Camp was not militia either; as all Flying Camp recruits signed six-month enlistments (many served an additional six months), they were called by Congress to fight directly under Washington, and thus were Continental troops. However most of Pennsylvania’s contributions of soldiers were pulled from Associator battalions—those who had not yet enlisted in the Continental Line—while some Associators took it upon themselves and left Pennsylvania to join Washington in New York as independent units.[15]

Meanwhile the Associators began to grow wary of their part in the war. As early as 1775, they had attempted to influence the Provincial Assembly to force every Pennsylvanian to share in the burden. After all, they had given not only their time, their sweat, and their blood to the cause, but most of them had lost their military equipment, their guns, and their uniforms over the course of two years. They had borne the weight of military service since the start of the war.

On November 25, 1775, the Assembly caved to their pressure, issuing a light fine (in the form of a tax) on all men between 16 and 50 who did not Associate, and offered a small bonus to those who chose to Associate. Most settlers on the frontier had the £2-10s needed to pay the tax, so recruitment efforts failed. The meager 2 shillings and 6 pence (it takes 20 shillings to equal £1) offered as an enlistment bonus was just not appetizing enough. After incessant complaining that this fine wasn’t doing the job, the best the Assembly could do was raise the fine to £3-10s and the bonus to an even 3 shillings, which had the same effect as repeatedly banging ones head against a wall to cure a headache.

In the fall of 1776, the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention—organized after the signing of the Declaration of Independence—voted upon and passed a stricter resolution, possibly at the behest of Benjamin Franklin who was on the Convention. They demanded that any non-Associating citizen between the ages of 16 and 50 would have to pay £20 every month that he refused to Associate, and those over the age of 21 were taxed an additional 4 shillings to the pound on the total value of their property—so if you’re estate was worth £300, you would need to pay 1200 shillings or £60! Yikes!

But the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly challenged the Convention’s authority to levy taxes and write legislation—something like that was only meant to be done by the Provincial Assembly itself (I mean, when they bothered to do anything at all). The resolution was deemed illegal by the Assembly and nothing would come of it—but that was their last hurrah. With the Association backing them, the Convention ratified the new Constitution in September 1776, and the Provincial Assembly was dissolved (thus the Convention had the last sinister laugh); the Committee of Safety was ordered to hand over all its records and accounts for review, and designated as the new Council of Safety.

In place of the old Provincial one, a new General Assembly took its place. In addition, the new Supreme Executive Council (SEC) consisting of 12 elected men—including a president and vice-president—oversaw the Executive branch of the state. This new leadership passed the Test Act which required all members of the House and SEC to swear an oath to the new government and Constitution of Pennsylvania, effectively making the legislative body a single-party system.

When the shiny new House of Representatives met for the first time, Associators had hopes that they would finally issue a law that demanded compulsory service, perhaps on par with what the Constitutional Convention had resolved a few months previously. Instead they reinstituted the exact same £3-10s which had failed previously, for who knows what reason.

Within the first few months of 1777, the Council of Safety also disappeared; all military activity was placed under the SEC from there on out. This is when the Associators finally had their edge. The SEC proposed a new resolution: the first-ever Militia Law in Pennsylvania that instituted mandatory enrollment. The law passed on 17 March 1777, and all white males between the ages of 18 and 53 were automatically enrolled in the militia. With the institution of this draft, the Associators disbanded.[16] This marks the end of the second major shift in government, but it is also where everything gets hairy for the person interested in the Pennsylvania militia because all sense of normalcy and common sense goes out the window. Brace yourselves, more charts are coming.

The Committees at the county level were also disbanded,[17] and in their place a County Lieutenant and a Sub-Lieutenant were put in charge of all military activity within their county. They held military ranks of Colonel and Lieutenant Colonel, but these men were actually civilian employees under the direction of civil government (so their ranks, while military-sounding, gave them no command in battle). The draft was instituted upon a class roll; that is, each county was to establish eight Battalion districts; these districts could encompass a handful of townships within the county, especially if there were several smaller townships with lower populations. A Battalion consisted of eight Companies of 80 to 100 men. Everyone who met the draft criteria was given a class number between one and eight.[18] Depending on the need, one or more classes could be called up at any given time to serve.

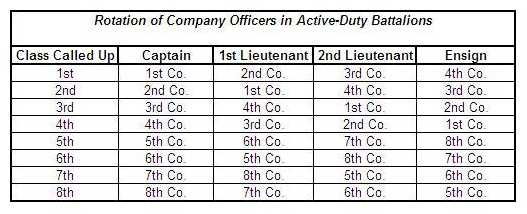

More hairiness ensues. All field officers were elected by rank, within their district, and then drew lots for seniority. So the Colonel of the 1st Battalion would have seniority over the Colonel of the 2nd Battalion, and so on. This seniority extended beyond the county; seniority of militia officers originated in Philadelphia and extended beyond it, circling outward. So Colonels, Majors, Captains, and so on, from Philadelphia County outranked those from Chester County. Chester County officers outranked Northampton County officers, and Northampton outranked Cumberland County officers. But just to make everything more annoying, all officers were on a rotation through the classes.[19]

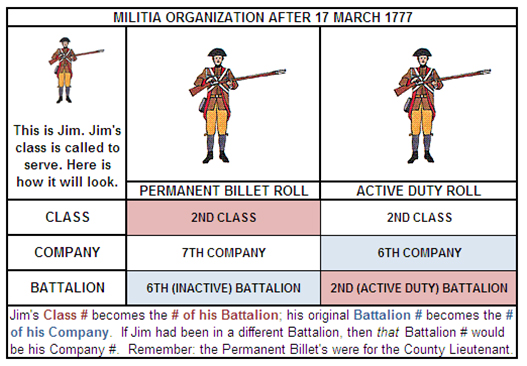

The County Lieutenants kept full rosters of men on what are known as Permanent Billet Rolls. Most Battalion muster rolls in the Pennsylvania Archives dating to after 1777 are precisely these Permanent Billets.[20] For example, the majority of the Companies listed in the 2nd Series, Volume 14 of the PA Archives (also those rolls from the 5th Series), post-1777 are actually these roll sheets.

When a class was called up, all members of that class were called up to serve throughout the county. For example, if the 1st Class was called, whether you fell under the 1st Battalion or the 7th Battalion, you were required to turn out. New rolls were taken by officers; these are known as Active Duty rolls. Many of these Active Duty rolls for 1777 do not survive.

So now we’ve discussed at least two different rolls (a Permanent Billet Roll and an Active Duty Roll); these existed for the organization of these Battalions, and therefore for each person (see above). By the ordinance of the Militia Law, the Class number became the Active Duty Battalion number. Additionally, when a class was called up, the men were assigned a different company number on the Active Duty rolls—the company number they were given corresponded to the battalion they were from on the Permanent Billet—than the company numbers on the inactive duty Permanent Billets.[21] Anyone called up had to serve not more than two months at a time; anyone who deserted was subject to a hefty fine of two-months’ pay, even if they deserted at the end of their two month tour.

There were exemptions. Initially those exempt were only members of the new General Assembly, county officials (Lieutenants and Sub-Lieutenants), and members of the SEC. Men who held religious scruples against bearing arms were made exempt later (except Quakers who were not specifically mentioned),[22] as well as certain tradesmen (like gunsmiths, coffin makers, and so on).[23]

But some laws were weakened. While the age of service was between 18 and 53, substitutes under 18 and over 53 were allowed; for example, a 15 year old son could serve in place of his father. Or a 60 year old father could serve in the place of his of-age son.

For the militiaman, substitutes were the bee’s knees. From the start of the draft to the end of the war, those called up found ways to avoid service. Sometimes these were legitimate health reasons, but not always.[24] So in December, the General Assembly passed two new supplements to the law: one that anyone unable to serve would be subject to a double-tax, and another that raised the fines for those seeking to avoid service by substitute.[25] But it didn’t seem to hamper the problem. As a result of all the avoided service, the County Lieutenants had a lot of problems fulfilling their quotas of troops.[26]

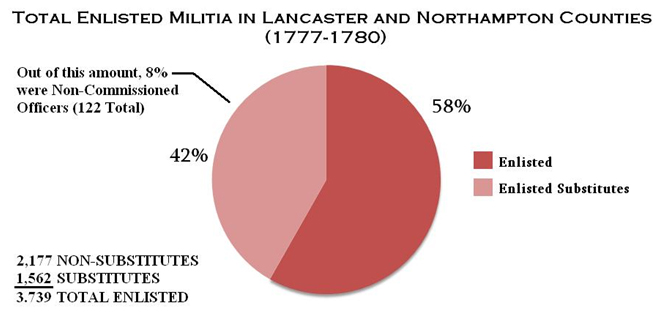

Substitutes made up about 42% of the total militia force between 1777 and 1780. In all those cases, only 7% of them were serving in place of a family member. The other 93% were essentially guns for hire, former Associators who wanted to serve, or friends of the family.[27] Below is an example of an Active Duty roll showing the amount of substitutes versus those who did their own service. From 1781 through the end of the war, substitutes became more common as men were rotated into other duties or refused to serve for other reasons.

Broadly speaking, most of the officers and County Lieutenants followed the Militia Law pretty closely from 1777 to 1779.[28] But by 1780, County Lieutenants were given more power over their county districts; rather than being called up to serve in Washington’s army, the militia were called to serve the needs of the county specifically. County Lieutenants could essentially ignore specific ordinances of the Militia Law;[29] Company officers were labeling their command whatever they wanted.[30] It was the militia, à la carte. Two or more Classes could be called up, and they would be designated as whatever Battalion was more useful to the Colonel. The further west one went in Pennsylvania, the more likely to find militia detachments serving longer tours (upwards of nine months at a time) in preparation for Indian attacks.[31]

The important information to take away from this article is that the Pennsylvania Militia system was just a messy pile of, well, you know. Let’s agree it was a disaster; it only polarized people, the high fines meant that poorer settlers with small families were automatically at a disadvantage, wealthier people could avoid the draft by simply paying whatever was owed, politicians were exempt (I mean, come on), substitutes were primarily mercenaries who took advantage of the system to rake in more coin, and the exemptions specifically singled out religious groups (like the Moravians, making them targets) or ignored them completely (like the Quakers).

But what are perhaps the most interesting bits are the social implications. Throughout the first two years of the war, outside of the minority elements of the population, the majority of Pennsylvanians did not want to fight. And in 1777, the Militia Law forced a difficult choice on all Pennsylvanians. Each one had to weigh the cost-benefit of showing up for an exercise drill, a muster, and service, or pay a steep fine. There was the concern that a County Lieutenant would force someone’s family member to serve in their stead, and the danger was very real on the wilderness.[32] For some, serving tours and showing up for exercises was not worth risking the death of the crops. Regardless of what they decided, there were serious consequences. If everything else about the militia still confuses you, at least remember that.

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: America Septentrionalis a Domino d’Anville in Galliis edita nunc in Anglia Coloniis in Interiorem Virginiam….1777. Source: Raremaps.com]

[1] For a full account of the social factors and legislation that this article draws from, see Arthur J. Alexander, “Pennsylvania’s Revolutionary Militia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 69:1 (January 1945 ), 15-25.

[2] The only time Pennsylvania seems to have had any sort of basic militia prior to the draft is during the winter months of 1776 into 1777. But these may have just been Associator units confused for militia. The details on these units are extremely limited and don’t tell us about their makeup; given that one of these units, originally raised by John Rosbrugh—the minister-turned-Colonel—was asked to resign his original commission in favor of a unit Chaplaincy and command was given over to an Associator officer, John Hays, leads me to believe these were similar to the Flying Camp, in that the rank and file were predominantly Associators.

[3] For example, see the Pennsylvania Archives, 2nd Ser., Vol. 14 for the Minutes of the Committee of Observation in Northampton County. Also see J. I. Mombert, An Authentic History of Lancaster County (J.E. Barr & Company: Lancaster, 1869), 199-200 for discussions and reproduced contemporary circulars dating back to June 12, 1774.

[4] In Northampton County, at the behest of George Taylor, a mob of some 100 or more people dissolved the current British provincial government nonviolently and replaced it with their own. However in New York and Maryland, Tories and former provincial assemblies did not get off so easily. For a brief overview of the persecution of Loyalists and Tories, see http://www.canadiangenealogy.net/chronicles/persecutions_loyalists.htm

[5] See the pleas of Governor Robert Hunter Morris, who had “in vain endeavoured to prevail upon my Quaker Assembly to pass” a militia law to aid the inhabitants of the backcountry of Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania Archives, Col. Rec., Vol., 6, 512, 738). For sources of these ‘sundry inhabitants’ and ‘melancholy events’, see the footnotes throughout my article “A Want of Arms in Pennsylvania”: https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/04/a-want-of-arms-in-pennsylvania/

[6] Thomas Verenna, “A Want of Arms in Pennsylvania”: https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/04/a-want-of-arms-in-pennsylvania/

[7] Though it wouldn’t be right to avoid the fact that some contemporary accounts refer to the Associators as ‘militia’; for example, between the 28th and 29th of July, 1775, York County held a meeting of the ‘Committee of Officers of Militia’ (Pennsylvania Archives, 2nd Ser., Vol. 14, 536-537); however by 1776, it seems as though this language would go away. York County would refer to them as Associators in future correspondence.

[8] From the Form of Association, which can be found at http://franklinpapers.org/franklin/framedVolumes.jsp?vol=3&page=205a

[9] Pennsylvania Archives, 2nd Series, Vol. 14, 592.

[10] Chester County had a high population of Quakers and remained pacifistic throughout much of the war. Contrary to this, Bucks County had a large population of Tories who sided with the British and refused to cooperate with Washington when the time came.

[11] According to Census records, Northampton County had an estimated 24,238 people in 1790; if these numbers remained consistent, the total number of Associators made up 9.7% of Northampton County’s population at the time. If we allow for a 25% increase from 1775 to 1790—a staggeringly high increase in population found only in later periods in Northampton’s history which would imply that about 6,060 people settled in the county between those dates—then the number of Associators would only make up 12% of the population. This number is still extremely low compared to population figures.

[12] Pennsylvania Archives 5th Ser., Vol. 5, 295; see also 8-12 for the new Articles of Association, resolved August 19, 1775.

[13] In January of 1777, prior to the passing of the Militia Law, the Council of Safety ordered Berks County Associators out to aid General Washington, but many refused to go. Under a show of power, the Council issued a decree that all affected men of arms who wanted to march should disarm all disaffected Associators and pay them for their wares and taken accoutrements and march to Washington’s camp (Pennsylvania Archives, Col. Rec., Vol. 11, 94-95).

[14] Incidentally, most Associator companies were led by an officer or group of officers wealthy enough to supply and outfit an entire unit. This is why Associator companies were so well equipped; many had their own flags, like the Hanover Associators, and their own unique style of uniform—dyed hunting frocks or shirts, for example, would indicate what county you might be from based upon the color of the dye used. This is very similar to how Volunteers were raised during the Civil War, with a wealthy supplier who would outfit a company or regiment with unique uniforms, muskets, and accoutrements.

[15] In some instances, full battalions of Associators joined with the Flying Camp, but did not enlist with them. This seems to be the case with Peter Kichline’s battalion of Pennsylvania Associators. Two of his four companies were understrength (one of 33 men and one of 44 men), which seems to suggest that these were not recruited specifically for the Flying Camp. Full rosters of the four companies under Kichline are found in the Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 2, Vol. 14, 557-570. Out of the four, one company, under Captain Arndt, originally mustered with over 100 officers and men, met up at Elizabethtown after the taking of Fort Washington; only 33 had escaped death or capture. Kichline himself was wounded at Long Island.

[16] They, like everyone else, would be required to compulsory service and would be called up in the manner described further on in the article.

[17] For example, the County Lieutenant elected for Northampton was John Weitzel on May 16th, 1777. The last entry in the Northampton County minutes of the Committee of Safety is dated on 14 August 1777. As indicated in the minutes, all accounts were to be settled.

[18] It was the responsibility of every County Lieutenant to keep records of all men between the stated ages on file; they cooperated with local constables to acquire this list.

[19] Chart inspired by Hannah Benner Roach’s chart in, “The Pennsylvania Militia in 1777,” The Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine Vol. XXIII, No. 3, (1964), 164. This article gives details on a lot—what Classes were called up when, and where they were camped for example—more than what can be covered here.

[20] A lot of people presume that these Billets indicate Active Duty service, when in fact they do not. While the lower Pennsylvania counties called up all eight of their classes in 1777, the frontier and northern counties did not. In addition, “Active Duty” doesn’t mean “saw action” or “fought in a battle.” To the contrary, Active Duty militia from Pennsylvania were relegated to tasks like building breastworks and redoubts, handling picket duty, and escorting prisoners and supplies. Some Pennsylvania Militia did take part in the battles of Brandywine, Germantown, and Whitemarsh, but only a handful of the lot saw actual combat. Most of the men were far removed from the fight as Washington did not trust them. While no Pennsylvania militia was present at Valley Forge, Washington did use them to secure supply routes for the army throughout his time camped there.

[21] So someone belonging on the 2nd Class, 7th Company, in the 6th Battalion district on the Permanent Billet, would have a new active duty muster roll arrangement of the 6th Company (because he belonged to the 6th Battalion) of the 2nd Battalion (because all men of the 2nd Class were called up, they were folded into the 2nd Class Battalion, or just the 2nd Battalion).

[22] Quakers were still required to attend drills and show up when called to serve, but many found substitutes as a way to keep their conscious clear, though still required to pay the standard fine.

[23] However, according to the new regulations under the Militia Law, tradesmen were not permitted to hold back any apprentice from serving, though their service was not obligatory. Additionally, Judges of the Supreme Court, delegates in congress, professors and teachers, ministers of every denomination, postmasters and riders, sheriffs, gaolers, the state attorney general, state treasurer and servants purchased were all exempted at some point through to the duration of the war.

[24] Most argued that crop season, replanting crops that died, or returning from service was why they would not turn out. But in many instances, men would remove themselves entirely from their original Battalion district to another to avoid being called up for service, as noted in The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682 to 1801, Vol. 9 (Philadelphia: Clarence M. Busch, 1903), 188: “And whereas many militia men by removing from one battalion or company to another, find means to escape their tour of duty….”

[25] The first supplement was passed on 26 December 1777, wherein those not able to serve were charged an additional tax equal to the tax they paid annually. The second supplement was passed on 30 December 1777 that instituted a £5 fine for anyone who left the company assigned to them and displayed on their Permanent Billet Roll. In addition, the law also stated, “Be it further enacted by the authority aforesaid, That if any militia-man shall neglect or refuse to march in person on the day appointed as aforesaid, such delinquent shall forfeit and pay within five days the sum of forty pounds to the lieutenant or nearest sub lieutenant, unless he produce a sufficient substitute of or belonging to his own family.” (The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania, 186).

[26] County Lieutenants complained about falling short of their quotas throughout the Philadelphia campaign. Thus on 5 April 1779 the fine was increased to £100 for those who refused to serve, and those who did not heed other services required (like showing up for regular drills) were forced to pay six times as much as they would normally pay, except for Philadelphians who would be required to pay eight times as much (because the law hates Philadelphia, I guess).

[27] See the slightly dated, yet still excellent study of substitutes written by Arthur J. Alexander, “Service by Substitute in the Militia of Northampton and Lancaster Counties (Pennsylvania) During the War of the Revolution,” Military Affairs, 9:3 (Autumn, 1945), 278-282.

[28] Around this period of time, the SEC authorized the forming of five companies of Rangers, to be outfitted and equipped by the state. These were not militia, nor were they Continental troops, nor Associators, but Independent companies meant to serve a longer tour of duty, made up of volunteers, to patrol the frontier under threat of Indian attacks.

[29] In the western frontier counties, this was already happening. County Lieutenants worked closely with the Continental officer in charge at Fort Pitt, and so militia could be called to serve tours of six months in addition to their standard two-month tour of duty as specified in the ordinances of the Militia Law. See my discussion here: http://historyandancestry.wordpress.com/2014/06/02/the-pennsylvania-militiaman-fighting-for-virginia-how-land-disputes-confuse-everyone/

[30] For an example, see the roll found in the Pennsylvania Archives, 5th Series, Vol. 8, 165. The roster contains a list of 28 names called to serve, of which 24 had substitutes in their place. In addition, the transcription suggests that the unit designations were no longer following the Active Duty roll patterns.

[31] Part of the problem with establishing militia companies after 1780 is that Captains were not consistent in how they marked their rolls. Some used checkmarks for positive attendance, other used checkmarks for negative attendance. Sometimes they used a variety of symbols and supplied a key. They also called their Companies whatever they wanted to call them, using their original designation or giving them a new designation—occasionally they would refer to their militia battalions as ‘of Foot’, like the ‘3rd of Foot’ (i.e., the 3rd Class of militia from such and such county). These designations are mostly found in the Fine Lists found in the Pennsylvania Archives 3rd Ser., Vol. 5-7.

[32] On 11 September 1780, in Sugarloaf Township, a company of men from the Northampton County militia, primarily from the Battalion district encompassing Allen, Moore, and Lehigh townships, were ambushed and massacred by Indians. They attempted to flee and were cut down next to a stream which flows through the region. They were found days later by local residents and a detachment of Northampton militiamen were sent out to Sugarloaf to bury them. This event came a few years after the massacre at Wyoming in which Pennsylvania and Connecticut militia were slaughtered; but previous to that were a series of violent campaigns against the frontier by the same Indians that left militia on high alert—fortifications were the primary target and were burned prior to the Battle at Wyoming. See what I’ve written about it here: https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/02/connecticut-yankees-in-a-pennamites-fort/

59 Comments

Very nice article. I confess I skimmed it because it is not my passion but I admire your work.

I also read your Town Square article in MC 6/14. This hate for our president & government is a big concern of mine as well.

See you Wed. nite.

Thanks Helene, I’m pleased you liked the article (even if you’re a skimmer!). Here is not really the best place to discuss my Town Square article, but we can certainly talk about it tomorrow night at the committee workshop!

Mr. Verenna, thank you for a very interesting, if complicated, article. It has assisted me in better understanding the environment affecting Washington’s efforts to collect intelligence in the period mid 1777 to mid 1778 in the Pennsylvania/Philadelphia area.

Ken,

No trouble at all. Glad I could assist! It amazes me how often things are interconnected.

Addendum: You will also want to read up on Brigadier General Lacey’s efforts in 1778 specifically. He was in command of all Pennsylvania militia located outside Philadelphia during the British occupation, and his troubles had a heavy influence on the region (particularly his hatred of the militia negatively impacted a lot of local residents against the patriots and particularly Lacey himself; in one effort to curb the trading in Philadelphia, he posted militia on the road to deter anyone from entering the city at all–instead his militia acted more like highwaymen and bandits).

Mr. Verenna, how often were men from other states recruited to serve in a militia? I’ve seen a case where men I am fairly certain were living in New Jersey and/or New York joined the Northampton County Militia to serve under men who had been neighbors and members of the same church in New York..

Janet, Yes, My 6X G-grandfather, Abraham Kittle was from Orange County and never lived in PA yet served as a Lt. in Northampton. The family helped found and belonged to the Dutch Reformed Church.

Janet,

Excellent question!

I wish I could tell you I’ve heard of that happening a lot, but I haven’t; do you have a year when they were recruited? It would also help if I had knowledge of the primary sources.

I can only think of this happening on a matter of circumstance; that being, when someone from another state took up residence in a county in Pennsylvania during the militia draft, maybe staying with family, they would still have automatically been added to the County Lieutenant billet rolls.

But most of the examples I’ve come across of people from other states serving in the Pennsylvania militia have been substitutes (guns for hire mainly). For example, while doing research on what the Pennsylvania militiaman would wear, I looked through a series of deserter reports and found that a few of the deserters had family or a second residence in another state (like Maryland or Virginia). So it did happen, how often I can’t say for sure. I documented a few of the deserter advertisements in my blog post on the subject here:

http://historyandancestry.wordpress.com/2014/06/11/what-did-the-pennsylvania-militiaman-wear-a-guide-for-the-perplexed/

Almost all cases were from the Philadelphia City, which makes sense because you would expect to find a broader range of travelers there and also where you would find the most recruiting for substitutes that are from other states. Needless to say, I would be interested to read a study on the percentage of substitutes that came from outside of Pennsylvania.

Thank you for the most interesting article. I am also reading a book by Larry Kidder – “A People Harassed and Exhausted” about a specific NJ militia unit as well as others serving along side – from both NJ and out of state. In reading your`s and Larry`s accounts of how the Militia responsibilities were carried out, it is amazing to me that they were able to function in any degree of effectiveness at all. Some of the detail is so very confusing ( at least for me ) that it must have seemed the same way for many people expected to serve. Yet, maybe they realized that the system was a piece of s— and took great advantage of it – bonuses, fines, substitutes, desertions, re-enlistments etc.

Even considering this non-sense, the state militias did in fact cause the Crown a good deal of trouble throughout the Colonies and throughout the War.

Regards,

John Pearson

John,

That’s actually a good inclination on your part. The militia in Pennsylvania specifically were not just undisciplined, they were pretty unreliable against the British and, later, the natives allied with the British. They just weren’t good soldiers. In the grand scope of things, that isn’t really a bad thing. But in the course of war, it’s a pretty important characteristic for obvious reasons. I’ve written that the militia have had their golden moments, but these are few and far between and for the most part they were completely ineffective. If we had to rely on just militia instead of the Continental Line, we would have probably lost the war.

If you consider how terribly the militia functioned in the Northwest Indian War that resulted in the complete defeat of every force heavy in militia vs how Anthony Wayne’s Legion of regular troops functioned, it’s a no brainer why a regular army was more necessary. Likewise, in the War of 1812, how horribly the militia did there as well. In fact it was only after how consistently ineffective the militia fared against better soldiers that Congress finally decided to create a standing army.

Tom,

Your observation on the persistent ineffectiveness of the militia is so true with its prevailing role becoming secondary only with the arrival of WWI; a very long time indeed.

I think it important to note that the whole standing army issue, which began in England with the Civil Wars over a century earlier, was essentially muted in that country by the time of the Rev War when the militia fell into disuse. However, for Americans, the army’s bad reputation, warranted or not, persisted and found an outlet in the politics of Federalist vs. Republican. Jefferson had a chance to expand the army in the early 1800s (think Louisiana Purchase and the need to police its frontiers), but failed to do so, sending up a rebuke to Federalists that came to discredit America’s abilities in the eyes of foreign countries and which contributed to the War of 1812.

Unfortunately, hidebound, myopic beliefs in the role, and capabilities, of the militia (which actually did serve tolerably well in earlier wars of empire) proved misplaced in a number of instances in the Rev War. But then, what was the alternative under the unique circumstances of rebelling colonists? Interesting topic.

Gary,

Well put indeed. In states where we see militia laws in place for a prevailing number of years prior to the Revolution, we see statistically better militia behavior (like Virginia, South Carolina, Massachusetts, &c.), though clearly not on the same level of von Steuben’s trained Continental Army of 1778 (or even in 1776, prior to thier training regimen).

If any sort of draft were to be issued, it should have been for longer periods of time (two months was an absurd amount–by the time a class was called, and able to march, and upon their arrive, they would have about as much time to acquaint themselves with camp and their duties before turning back around and marching home), and probably should have been a draft into the regular Line rather than militia.

But you sum up the problems nicely. Thanks for that.

I have found this resource helpful on a number of occasions for information regarding the development of the nation’s military and commend it for your review (see, in particular the discussion starting on page 10 for the Rev War period): https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112012299092;view=1up;seq=31

I think the militia performance can also be looked at by region. The coastal areas that had not been under pressure from Indians for a generation or more tended to have less trained militia who performed poorly. As one approaches the backcountry, a completely different soldier appears. Not afraid of combat and tend to do very well. I understand the situation in PA and New England is a bit different but, for the southern states, we saw a regular pattern of eastern militia doing poorly while western backcountry militias did better. And, of course it makes perfect sense that way, the backcountry folk were called out from time to time on actual emergencies and therefore took their training and service more seriously. And also tended to just simply be a bit more rugged type of individuals.

Thanks for the comment; this might be true for other states but for Pennsylvania this is not the case. Two key points to contention:

“As one approaches the backcountry, a completely different soldier appears. Not afraid of combat and tend to do very well.”

That’s not true for Pennsylvania. The militia on the western frontier were just as ill equipped to handle combat and the needs of fighting than their fellow soldiers in the east. The same goes with the northern frontier. In fact, the frontier counties were less inclined to fight the British than their eastern counterparts because they were afraid to leave their families to fend for themselves while they were forced to trek through the wilderness. Stories abound from Westmoreland about settlers avoiding the draft by claiming they were Virginia or Maryland settlers so the County Lieutenants couldn’t recruit them into service. In York and Cumberland Counties, several people rioted against the militia law–and York specifically saw an uprising of German immigrants who gathered near 200 (some estimates say 500) and agreed to not only ignore all summons to serve in the militia, but they would support each other in mutually ignoring paying for fines.

I think we need to stop and consider Pennsylvania’s militia more broadly too; several Continental officers complained that the militia law actually reduced their Line recruitment because the militia substitutes served less time and were paid more. It was better for a Continental whose time was up to become a substitute rather than rejoin a longer term of service in the Line. And that caused a lot of problems between soldiers of the Line (some members of one of the Additional Continental Regiments on the frontier accosted a few militia officers and a magistrate in retaliation for supposed slights against them and attempted to forcefully recruit them back into Continental service).

“And, of course it makes perfect sense that way, the backcountry folk were called out from time to time on actual emergencies and therefore took their training and service more seriously.”

Again, this isn’t correct for Pennsylvania. Leading up to the Revolution, all the frontier forts were occupied by British troops (like the famed 42nd Foot) and under command of General Thomas Gage for the protection of the frontier. Because Pennsylvanians were so poorly equipped and few had guns to speak of, mounting a suitable defense was nearly impossible (see my article published here: https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/04/a-want-of-arms-in-pennsylvania/).

Well obviously the militia had tremendous problems in dealing with the enemy due to their inconsistent method of remaining in the field and poor training. None the less, overall, just by being present at various battles and skirmishes did in fact require the enemy to devote some measure of their resources and time to deal with them. Battles such as Oriskany where a decent size force of militia held on against trained Crown forces and Indians is an example.

The militia, depending upon the colony, performed with varying degrees of success or failure. Evidently, Pennsylvania struggled as did others. I still believe that the various militia units in the Colonies helped to win the War over an 8 year period.

John Pearson

I think this is an astute position to take. To be clear, I make no suggestion in this article about the militia beyond Pennsylvania. I can’t say for sure for other colonies during the war, as my area of study is Pennsylvania specifically, but from introductory volumes on the war in general and from a good grasp of the militia in the War of 1812 and the Northwest Indian War, militia time and again failed to provide any sort of adequate defense against regulars. Did they get the British to commit more resources? Oh goodness, yes. But were they accomplishing any task that effectively made a variable, measurable difference? In Pennsylvania, not really. In South Carolina or Massachusetts? I can’t say with any degree of accuracy. Even New Jersey fared slightly better than Pennsylvania’s militia, though Larry Kidder would be the one to ask about that.

As a descendant of of number of those discussed above. There is no doubt that Pennsylvania during this period became politically the most radical of all the Colonies/States. Further, Pennsylvania was remarkably intolerant towards pacifists and more particularly Friends during the term of Joseph Reed as President of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, from December 1, 1778 to November 15, 1781, and of course the Militia Laws were part of this.

Edwin,

Thanks for the comment! I discuss the darker side of the Pennsylvania militia and associators in my article (published on this site): https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/02/the-darker-side-of-the-militia/

You are correct to a large degree; though the local Committees did try to prevent the persecution of Moravian settlements prior to 1777 (and Congress ordered Continental troops into Bethlehem, PA, for example, in order to prevent the Allentown Associators from forcing enlistments or robbing them of goods and supplies). When the militia law went into effect, it became more difficult to control the troops. For example, I discuss an instance in the article linked above about the rounding up of Moravian men by the militia. The County Lieutenant didn’t even know what was happening until they were paraded through the town as traitors and locked up in the gaol.

11 September 1780, in Sugarloaf the number of men don’t add up 10 dead ?

6 prisoners or escaped is not 40 men that started out ?

Hi Steve!

I just did some fresh research on this and an article is forthcoming in July which will answer all your questions about the Sugarloaf Massacre. The short answer is that 41 men set out from Fort Allen and were ambushed. The earliest and best report suggests that ten were killed, 3 were captured (one eventually escaped), and many more were wounded (how many were wounded varies). Later reports indicate 15 were killed, but this doesn’t jive with extant records. But worry not, like I said, a very detailed article is forthcoming in July which will deal directly with this event and the scholarship on the subject to date.

11 September 1780, in Sugarloaf 10 dead 6 escaped or prisoners is not 40 men?

See answer given above.

http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/rg/di/r17-522WarranteeTwpMaps/r017Map2910LuzerneSugarLoaf.pdf

indian path shown on this map Sugarloaf Massacre

The following is an official letter, dated September 20, 1780, and throws some light on the transaction—copies from the Pennsylvania Archives:

I take the earliest opportunity to acquaint your excellency of the distressed and dangerous situation of our frontier inhabitants and the misfortune happened to our volunteers stationed at the Gnaden Hutts; they having received intelligence that a number of disaffected persons live near the Susquehanna at a place called the Scotch Valley, who have been suspected to hold up correspondence with the Indians and the tories in the country. They sat out on the 8th inst. for that place to see whether they might be able to find out anything of that nature, but were attacked on the 10th at noon about eight miles from that settlement, by a large body of Indians and tories (as one had red hair). (Our men numbered 41; the enemy supposed twice that; other estimates placed them at 250 to 300.) * * Twenty out of forty-one have since come in, several of whom are wounded. It is also reported too that Lieut. John Moyer had been made a prisoner, and made his escape from them again and returned to Wyoming.

On the first notice of the unfortunate event, the officers of the militia have exerted themselves to get volunteers out of their respective divisions to go up and bury the dead. Their labors proved not in vain. We collected about 150 men and officers from Col. Giger’s and my own command, who would undergo the fatigue and danger to go there and pay that respect to their slaughtered brethren, due to men who fell in support of the freedom of their country. On the 17th we arrived at the place of action, where we found ten of our soldiers dead, scalped, stripped naked and in a most cruel and barbarous manner tomahawked, their throats cut, etc., whom we buried and returned without even seeing any of their black allies and bloody executors of British tyranny. I can not conclude without observing that the Cols. Kern, of the third battalion, and Giger, of the sixth, who is upwards of sixty years of age, together with all the officers and men, have encountered their many and high hills and mountains with the greatest satisfaction and discipline imaginable; and their countenances appeared to be eager to engage with their tyrannical enemies, who are employed by the British court and equipped at their expense, as appeared by a new fuse and several gun barrels, etc., bent and broken in pieces with a British stamp thereon, found by our men. We also have great reason to believe that several of the Indians had been killed by our men, in particular, one by Col. Kern and another by Capt. Moyer, both of whom went voluntarily with the party. We viewed where they said they fired at them and found the grass and weeds remarkably beaten down; they had carried them off. * *

Setphen Balliett, Lieutenant-Colonel.

The following extract from a letter written by Col. Samuel Roy, dated Mount Bethel, October 7, 1780:

Col. Balliet informs me that he had given counsel a relation of the killed and wounded he had found and buried near Nescopeck. As he was at the place of action, his account must be as near the truth as any that I could procure, though since Lieut. Myers [Moyers], who was taken prisoner by the enemy in that unhappy action, has made his escape from the savages and reports that Ensign Scoby and one private was taken with him and that the party consisted of thirty Indians and one white savage; that they had thirteen scalps along with them; that several of them were wounded, and supposes some killed.

It is difficult, impossible to reconcile the conflicting figures above given as to the number of our men in the expedition or the number of the enemy. In Col. Stephen Balliett’s account it looks as if there were forty-one in the expedition, and twenty returned; but there were not that many is evident. So far only thirteen are accounted for, and yet others, supposed killed, finally returned, having escaped from the scene of slaughter. Altogether sixteen men are really accounted for—ten lay dead and this number were buried, and six escaped or were taken prisoners. Except Capt. Klader, who were these fallen heroes? No names are now obtainable of the nine, beside the commander, whose dust is in the unmarked graves where they fell. Is it possible the burying party did not know their names, and, therefore, never gave the world the short, bloody list? They were a little band of volunteers, not even enrolled, nor were there any company books or records from which we can transcribe the names for the bright immortality they so richly earned.

Hi Steve,

Thanks, yes, I’m quite familiar with the Pennsylvania Archives and their particular discussion of the massacre. I promise you that the article, that is already accepted here at the journal, will cover all of this and more. You will not be disappointed! Please be patient. It is publishing in July.

Thanks!

original Northampton papers militia

https://historyandancestry.wordpress.com/2014/09/06/revolutionary-war-manuscripts-northampton-county-pennsylvania/

Steve,

Thanks for posting that. It’s my blog.

Tom

sorry i read to fast

capt d klader came from local stores

https://books.google.com/books?id=XbA_AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA126&lpg=PA126&dq=sugarloaf+massacre+flintlock&source=bl&ots=iBei1015RV&sig=NCFYyzI-LcLU-9yqlQc3_CsNSN0&hl=en&sa=X&ei=rIORVYm9OoX2-QGcz67oBg&ved=0CDYQ6AEwBDgK#v=onepage&q=sugarloaf%20massacre%20flintlock&f=false

Steve,

I appreciate the fact that you are really enthusiastic about this subject, but I continue to ask you to be patient with posting comments on the Sugarloaf Massacre. Not only is it irrelevant to this particular thread, but my article on the Sugarloaf Massacre is to be published in a few weeks. After you read it, I welcome your comments. For now, if you would, please consider reserving any additional thoughts on this subject for the comment section on that article, when it publishes.

Thank you,

Tom

sorry i will be patient i am near the area of Sugarloaf thanks

I am trying to find information on Abraham Hershe (spelled a few different ways) (1768-1852). He passed away in Iowa, however, he was from Lancaster County and moved westward around 1850. I would also like to know if he served in the Pennsylvania Militia during the Revolutionary War. Thanks in advance.

Hi Luke,

Thanks for commenting. It would help to have more information. For example, do you have any information on his service, years he served, etc…? That information really goes a long way towards figure out details.

Also, searching through the Pennsylvania Archives (or contacting them directly via the PHMC) is a good way to acquire details and documents for a rather inexpensive fee ($15 will get you copies of original manuscripts with your ancestor’s name).

Honestly, your best bet is to get with the Sons of the American Revolution in your region. They usually par new members up with a genealogist who helps research their family history.

Hope that helps.

I would be interested in your thoughts on the status of Colonel Samuel Miles Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment, raised in April-May 1776. Although this appears to be a voluntary enlistment unit of state troops as opposed to being an Associator unit, I have seen a confusing reference to it as being raised under the Articles of Association. I have not seen a transcription of the roll of the unit, but I would assume that individuals serving as officers in it almost certainly served as Associator officers at some point.

Walter,

Good question. The Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment and Battalion of Musketry were raised specifically by the state, not as Associators but as part of the Pennsylvania Line.

If memory serves (sorry, don’t have the time right now to search through the records to double check this-so please be sure to look through the revised Articles yourself when you can and let me know) the officers of the regiment and battalion respectively would have signed the Articles of Association when they were rewritten in 1776, as acquiring a commission at the time was dependent upon the signing of the Articles (e.g., to prove ones loyalty). That’s why so many of the officers have commission dates about 6 April 1776 (the previous day, the 5th of April, is when the revised articles, known as the Rules and Regulations for the Better Government of the Military Association in Pennsylvania, had been accepted in the Assembly and thus commissions could be signed the following day–the 6th).

If you look at the enlistment dates of the privates in the regiment/battalion, you see they are really all over the place within a six month period. Some enlisted in March, others in April, some in May, and so on. In other words, this was a standard Line unit with a broad enlistment range. Maybe some of these men were Associators prior to enlisting, but it is difficult to say without comparing lists (and again, I don’t presently have the time). However, if they served in the Pennsylvania Line they did not also serve in the Associators at the same time. It would have been one or the other.

The officers, similarly, may have been Associators prior to enlisting in the Pennsylvania Line; however once they received their commissions in 1776, they would have been in the service of the regiment they were commissioned with unless reassigned by the Assembly, they resigned from that position, or some other special exception.

I hope that helps.

Tom

Hello. I am trying to find out the definition of a position (job) listed on a York County PA Militia roll. The roll would have been transcribed as it was typed. The position I am curious about is listed as “Marsel”. It was listed with 3 other positions and the name of the soldier assigned. Those 3 other postions were Clerk, Court and Fifer. I’ve been asking around and some one ask if it could have been a transcription error and should have been “Marshall”. Any info you can give me would be appreciated. Thank you in advance.

Hello,

Looks like the roll is from September of 1788? Based solely on the transcription from the PA Archives, it is my opinion that ‘Marsel’ should be read ‘Martial’. Without seeing the original (or a good facsimile) manuscript with the names listed, it is impossible to say with any certainty; however, I would say he was one of the battalion’s court martial men. It is possible, as you say, that this is a transcription error of the title.

My suggestion would be to contact the PHMC directly and see about acquiring a facsimile of the original document. It will cost a few bucks, but you may have an answer when you get it.

Can you help me understand the meaning of this statement found on the website:

https://archive.org/stream/musterrollsetc00montgoog/musterrollsetc00montgoog_djvu.txt

“William Soar, of the Fourth Company, in the room of Francis Titus who has removed to Chester County, Sept 24, 1781.”

Does that mean William Soar was his substitute or does it mean something else. Francis Titus was from Bucks County and I know he died there so I’m not sure why he would have gone to Chester County.

Yes, Soar would have simply been replacing Titus in whatever particular capacity (“in the room”) that Titus had. We see that phrase repeatedly when someone has vacated a role for whatever reason and then someone else comes in to take over.

Gary is correct… “William Soar, of the Fourth Company, in the room of Francis Titus who has removed to Chester County, Sept 24, 1781” indicates that Francis Titus either left the county permanently or dodged the draft in September of 1781 for his class (I haven’t had the time to investigate his particular circumstance), and so William Soar volunteered to serve as a substitute in place of Titus, and so was granted extra bounty money.

Ah, sorry, I see you said he died in Bucks County. That implies that Titus then dodged the draft by leaving the County. This was extremely common early on in the war and as a result they had to amend the militia law to include extra punishment (in terms of higher fines and restrictions) for those who left their County to avoid compulsory service. It happened regardless and many people stayed away for months or longer (often with family in other parts of the state) to avoid paying any fines owed.

Another possible explanation, which isn’t so condemning, is that Titus had a family member in another County who was sickly and he gained permission from the County Lieutenant to excuse himself from his service to take care of them and their relations and duties.

So one way to examine the claim is to look through tax records of both Bucks County and Chester in 1781; I see that Francis Titus, Senior and Francis Titus, Junior both had property in Falls Township, Bucks County (and were neighbors with other Titus’s) and paid on a combined total of 533 acres of land. But in Chester County I also find a Francis Titus living in West Caln Township, with 202 acres of land.

Also looking through the State of Accounts of County Lieutenants in Bucks County, between 1780-1783, it does appear Francis Titus, Jun., had been fined for not turning out in the militia (PA Archives Ser. 3, Vol. 6, p. 105). So it doesn’t look innocent. But again, I don’t know his story specifically. This is just what I found with some cursory research.

I hope this helps.

Thanks so much. Here’s some of what I know of the Titus family. Francis Titus Senior had five sons according to his will dated June 30, 1783. One named Tunis is mentioned as deceased and I believe he is the Tunis Titus who joined Loyalist regiment of New Jersey volunteers and likely died in South Carolina. (That there was a Tory in in family is confirmed by a 1920 letter suggesting as much.) Two Francis Titus’ (I assume the father and son although the father would have been in his 60’s) as well as another son named Samuel who is my ancestor show up on the associator list for Plumstead in Bucks County dated 21 August 1775. Only one of the Francis’, presumably the younger one continues to appear in military records. Eventually he is promoted to Lieutenant.

There’s more all of which appears on the surface strange. I know the family was Quaker before the war so that may explain some of the strangeness. Perhaps some in the family were torn between their upbringing and what they saw happening around them. So I’m trying to better understand how the Quakers reacted when fighting came to their doorstep. Any suggested reading?

There are a lot of great volumes on Quakers in Revolutionary Pennsylvania–as well as many published diaries and correspondence from Quakers of the period.

Some diaries worth looking into:

Elaine Forman Crane, ‘The Diary of Elizabeth Drinker: The Life Cycle of an Eighteenth-Century Woman’

Susan E. Klepp & Karin Wulf, ‘The Diary of Hannah Callender Sansom: Sense and Sensibility in the Age of the American Revolution’

Also the diary of Sarah Fisher: https://journals.psu.edu/pmhb/article/viewFile/41415/41136

That should be a decent start. Good luck in your research!

I enjoyed your article very much. A relative of mine was Captain Valentine Houpt, who served in the Berks militia in 1781. Do you have any suggestions as to where I might start to research him in that capacity? Thank you very much! Susan

Thanks! I realize this is an old comment. I always recommend reaching out to the PHMC with questions. They are very approachable and charge only $15 for the time. They will also (at least in past instances) send you any facsimile copies of anything they find related to your ancestor (the $15 covers the paper and ink for the copies).

I am descended from 2nd Lieutenant William Stewart, 3rd Company, 2nd Battalion, Cumberland County Militia, called up July 1777 and again in September 1778. His name appears again as Ensign called up August 15, 1782 for 11 days under Captain Harrell’s (Horrell’s) Volunteer Company of the 7th Bn raised to fight Indians. First of all, I thank you for writing this article. I have spent about five years off and on trying to untangle William’s service record. Finally, now that I understand the role of the classes, I have been able to do so. Happy day! I’ll be reading more of your articles as well.

One quick question: How long did the elected officers retain their position? Until they resigned it or retired? Were they reelected at each alarm?

Sorry for the long wait for the answer. I am happy you have found it useful! All officers held position for the duration of the three-year term. Of course an officer could resign or be removed, either for personal reasons in the former or due to questionable character or loyalty in the latter.

what age were the drummer boys in the PA militia during RW? were they between 13 and 18? I have an ancestor who was listed as the drummer boy initially but later is listed as a private

Good question! I would have to research this more.

This information is HUGE and significant! I’m a military genealogist and I am always challenged to explain the differing numbers for a person who served over the course of the war and always had different battalions and companies. Thank you for your publication!

Happy you liked it!

I know this is an older thread but……

Heinrich Reinhardt Alspach sr. was my grandfather of how many greats I am not sure. How do I research him?

Henry was a private from March 1777 to March 1780 under Captain Wills, Company Commander 3rd Battalion Berks County Militia March 1776 under Col Slough – Battalion of Associators of Lancaster County Militia [1]

Records show that Heinrich and two of his sons, Michael and John, fought in the Revolutionary War. Following his terms in the army, he was given two tracts of land in what was then Virginia Military Reservation. The Virginia Military District includes some of the present Fairfield County, Ohio.

I would recommend getting in contact with someone from a lineage society, like SAR, who have dedicated genealogists who can help you with your search. They are particularly amicable to those who are interested in joining, but even if you don’t want to join, they are a great resource and are (in my experience) full of wonderful people with lots of knowledge.

How did the rural militia units in the Revolutionary War find out that they had been called? Did they read their names in the local paper or did someone on horseback come by their farms to tell them? Also how long did it take between militia being called up and actually reporting for duty?

Good questions! The officers of each company were responsible for issuing the summons which were left at the homes or business of the individuals in a class whose turn it was to serve. These were often issued at the discretion of the officers, though, and it was the responsibility of the person receiving notice to turn out on the given day for active service.

At the day of muster, a roll was taken of those who turned out. Those who did not turn out were, subsequently, fined and a substitute found to replace them.

Notices of drill (‘exercise’) were also published in papers (you see this in Philadelphia especially) though my German is a bit rusty and many of the German papers from that time are long gone, so I can’t be sure how often this happened in rural farming communities (like in Lancaster and Northampton counties).

Thank you for a very interesting article. I was browsing some records of York and Cumberland Counties for my ancestor William Scott when I saw him listed as a County Lieutenant. Not knowing what this office was, I wondered if it was related to the English Lord Lieutenants. Apparently, it was, as the original duty of the English Lord Lieutenants was the raising of the militia. As to the abysmal level of competence of the militias, John Elting does a fine job of describing the militias of the War of 1812 in Amateurs, To Arms!

Glad you liked it!

Hello,

My ancestors named Matthias and Henry Colflesh committed to the Philadelphia associator’s on October 13, 1778. I’ve been trying to find out why they were needed during that period of time. Was there any pending military action during this time, or if it was just for garrison purposes? I’ve tried to find this information out myself through research, but I’m hitting a brick wall.