Remember when I wrote that nobody ever said life on the Pennsylvania frontier was easy?[1] Well, as it turns out, it was a lot more difficult than even I previously thought. Between battling it out with Connecticut Yankees and Indians, dealing with localized violence, and having to put up with a relatively untrained and undisciplined militia (who would occasionally loot your stuff), it was a grim situation all around. But do you know what made matters even worse? Those times when a gun would have come in real handy—you know, because Indians—but there were no guns to be found. Pennsylvania seems to have been one of the few colonies in America where guns were scarce—particularly those of military quality.[2]

This runs counterintuitively to what we might believe; in popular culture it is easily envisioned that frontiersmen were always armed (probably because Indians). Yet the evidence does not support this conclusion. For obvious reasons, this was a troubling problem for Pennsylvanians prior to, during, and after the American Revolution. General Washington, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, various Committees, and other contemporary records attest to this troubling fact, and for the Continental Army, this was a stumbling block that was difficult to resolve—at least until the French decided to supply American soldiers with arms.

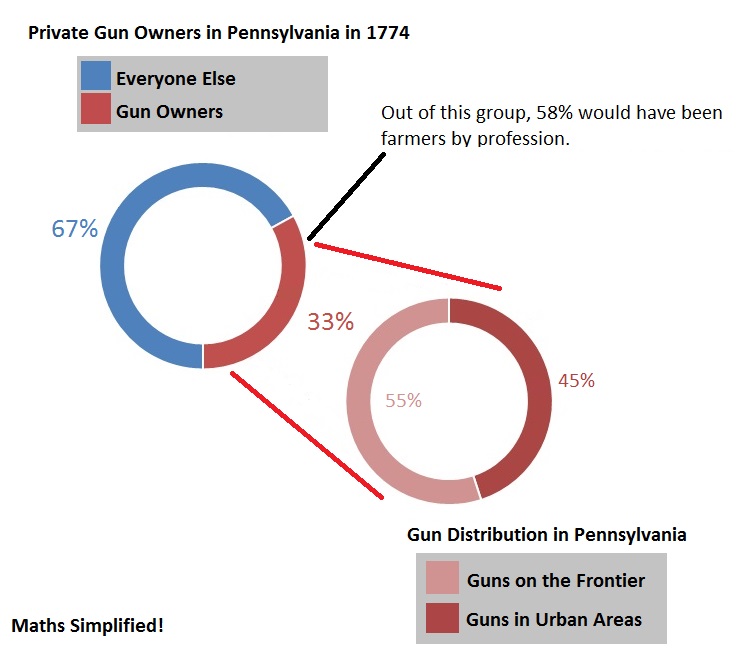

But first let’s get right to the numbers (I know, I know…we all hate math, but bear with me because it matters). Following Michael A. Bellesiles’ scandalous book,[3] James Lindgren and Justin L. Heather published the most definitive gun percentages based upon probate inventories known to me.[4] Despite the fact that (according to these records alone) 54% of the population of Colonial America in 1774 appear to have been armed,[5] only about 3 out of every 10 male estates in Pennsylvania list guns in their probate inventories.[6]

On average, 55% of those guns in Pennsylvania were distributed amongst the frontier and 45% were found in urban centers. In terms of profession, 58% of gun owners were farmers; this does NOT mean that 55% of Pennsylvania farmers owned guns, but that, of the 30% of households that had guns, just over half were farming households.

Eyes glazing over yet? I hope not, because the math part is done—at least for now. These numbers correspond to the contemporary written records we have from the time. What surprises me is how few firearms we find in usable condition during 1774 considering Pennsylvania’s tumultuous history. If any state had a reason for stockpiling huge amounts of arms and ammunition, it was Pennsylvania.

You see, Pennsylvania was a hotbed of French and Indian incursions from 1755 thru 1759. Following Braddock’s Defeat, the French grew bold and with their native allies launched a campaign of death and destruction on the Pennsylvania frontier (because launching a campaign of flowers and fancy things was just not cool). Hundreds of people were killed, homes were destroyed, livestock slain, and crops burnt.[7] If you think this was a hot mess of confusion and chaos, you’re not far off the mark. So why was the frontier so indefensible? Well, as you may have guessed (from the title and all), there just weren’t enough guns to mount a defense, no defensive structures had been built, no Militia laws were on the books, no firearm regulations existed like they did in other colonies.

Primary sources are quite clear that the frontier counties (which were essentially all the counties outside of Philadelphia—not even kidding) were completely unable to mount any defense because of the extreme want of arms. The evidence is pretty air-tight; a petition from York laid out some of the settlers’ concerns, specifying that “the inhabitants here in the greatest confusion,…and on examination find that many of us have neither arms nor ammunition….[and] it is probable before this comes to hand part of these back counties may be destroyed.”[8] George Stevenson, one of the Justices of the Peace, wrote to the Secretary of the Province of concerns about gunlessness in no uncertain terms; “for God’s sake either…send us Arms, Ammunition, & Blankets…or else our Country shall be deserted.” The residents in Lancaster County also petitioned the Provincial Council for assistance on November 1, 1755 when word reached them of the incursions, writing that they were in a “Melancholy and Distress’d Situation,” that “there are not one half of the People of this County who have arms, and there is not Ammunition by any means sufficient for those that have.” The residents demanded the Council begin “furnishing those that are willing to do their Utmost for the defence of their Family’s & Bleeding Country” because the county was “destitute of all manner of Warlike Stores.”[9]

It would take Benjamin Franklin and a few companies of Associators, armed with mainly provincial guns donated by the governors of Virginia and New York, to bring any sort of defensive strategy to the colony.[10] When Franklin arrived in Bethlehem with some of his command, he wrote of their state, “I arrived here last Night…. The Lieutenant, who commanded, had Fifty-two Men with him at Gnadenhutten, mostly Labourers, who came with Axes to look for Employment, but without Arms. A Detachment of the Company was down here with the Captain, to escort up some Waggons with Provision; and another Party was out to meet the Waggons, so that among the Fifty-two Men they had but Twenty-two Guns.”[11] And not all of those guns were usable.[12]

Even following these events, the issue of gunlessness did not improve. Reports from block houses and forts along the Susquehanna and Delaware Rivers indicate that of those men turning out for militia duty in February of 1758, only 34% (147 out of 423) had their own firearms (no indication how many of those firearms were useable or military-grade). The rest were armed with provincial guns supplied by the Provincial Government under Benjamin Franklin’s direction. This is consistent with other contemporary data.[13]

I draw attention to these incidents because they really establish a dire history of gunlessness prior to the American Revolution, not just in the urban areas of Pennsylvania but also in the frontier Counties. When order was restored in 1759, the predominantly Quaker assembly permitted the passing of temporary Militia Laws, under the guidance of Benjamin Franklin, which allowed for a more suitable defense, but it was far from perfect. The pacifism of the Peaceable Kingdom fell away. So you’d think that maybe they’d acquire more guns after seeing the brutality of man, right? Right?

Well, no. During Pontiac’s War, that other Indian rampage that flew through Pennsylvania a few years later where dozens of settlers were killed again, the situation was just as terrible. In some correspondence between Colonel James Burd and William Allen in 1763, Burd writes, “I collected the men of town [of Northampton] together…but found only four Guns in the Town.” Two of the guns found were broken and unusable.[14]

Somehow after all of this, one would think Pennsylvanians would be rushing to acquire firearms. Perhaps some did (the probate records from 1774 may indicate an increase in private ownership following the incursions). But when open war with Great Britain breaks out in 1775, we see the same trouble—wherein large bodies of men called up for service are mostly or completely without a firearm of any sort.[15]

Here’s more math as an example (sorry): according to the Cumberland County records,[16] when war broke out, they put out a general call for arms—these included arms on hand for Associators and militia in public County magazines (numbering about 1500), personal firearms confiscated or donated by nonassociating members (“several hundred”), and stockpiles on hand from the previous war (amounting to an additional 70 guns) which had gone unused and fallen into disrepair (many of which were sent to Carlisle for repair). If we assume that the “several hundred” firearms donated from homes and nonassociators is 700 (a liberal assumption), this brings the total firearms available to Cumberland County residents to about 2,270. But only “several hundred” of them were acquired from private owners.

Unfortunately no reliable census data exists for Cumberland County prior to the establishment of the Federal Government. But according to the 1790 census the population within the original (1775) borders of Cumberland (Cumberland divided into multiple counties after the war) is some 33,870 people.[17] As Lindgren and Heather point out, the average family size in America at the time was 5.7 to 6.2.[18] In other words, there were an estimated 5,463 households in Cumberland County. If 700 firearms were donated or confiscated from private owners, and if we assume that every gun was from one household (1 gun per household—a bizarrely irrational concept since some households had more than one gun and more still had none), then only 12.8% of Cumberland County homes had access to personal firearms (more had access to public magazines). Even if we assume only half the firearms from households were presented to the County Lieutenants (and the other half were greedily kept in personal possession) that only brings the total number of households with guns to a little over 1/4 (25.6%).[19]

These numbers match what we see in the rest of the Pennsylvania (though some Counties fared better than others) and additional contemporary evidence from frustrated officials. When militia companies were finally raised in 1776, Washington wrote to the Committee of Safety in Pennsylvania that the militia had been showing up in his camp without any guns. He stated plainly:[20]

“I have not a Musket to spare to the Militia who are without Arms. This demand upon me, makes it necessary to remind you, that it will be needless for those to come down who have no Arms, except they will consent to work upon the Fortifications, instead of taking their Tour of military Duty, if they will do that, they may be most usefully employed.”

During the month of August, 1777, five months after Pennsylvania’s most radical Militia Law passed, Adams watched as militia turned out for muster in Philadelphia. He wrote home on the 26th that “The militia are turning out with great alacrity both in Maryland and Pennsylvania. They are distressed for want of arms. Many have none, others have little fowling pieces. However, we shall rake and scrape enough to do Howe’s business, by the favor of Heaven.”

Adams may have been a little idealistic. That same month, Colonel Galbraith was working to get his Lancaster militia battalions on the move, but came across the issue of acquiring enough firearms to meet his quota of men needed in the field. His letter to President Wharton (the first President of Pennsylvania) is telling:[21]

“Since my letter to you of the 5th Ins’t I have had a General Tower [sic – tour] thro’ the Battalions already formed in this County, & have set nearly three Eighths of the Battalions on foot for the Camp at Chester, (as I rec’d no answer to my last) most of which I hope will arrive at Camp by the middle of next week. They have neither arms, accoutriments, Camp-kittles, &c., except blankets, which they had Perticular orders to Procure. Their Number supposed to be near 1,000 men, the militia of the Borough I have detained on Acc’t of the Prisoners. I have consulted the gun-smiths of this county as to making of arms & they in a General way hold out from £8. s15. to £9 for Musquetts & Byonet; Shocking prices! I did not think proper to agree with them at such rates, but at the same time proposed to give them the Philad’a prices: in answer to which they were willing to make arms on the same pay the Philadelphians did, provided they could procure Materials at the same rate, which they were at this time not possessed of. As to the 600 stand of arms lately made in this county I am afraid there will be a poor account of them.”

A few days later, during the beginning of the Philadelphia campaign, James Irwin received his commission as a Brigadier General from the state and was sent to the camp at Wilmington, where he took command of the newly formed 2nd Brigade of Pennsylvania militia. While the 1st Brigade would move with the Continental Army, he would be forced to remain there as most of his 1200 men were without arms with which to fight.[22]

At their camp at Chester, on August 29, 1777, General Armstrong, commanding another large contingent of Pennsylvania militia, pleaded with President Wharton and the Committee of Safety at Philadelphia for weapons:[23]

“I ordered Coll. Bull to furnish Council with a general return & a copy to the Board of War, and shall send another as soon after our junction at Camp as possible. The want of arms being our great complaint, at a crisis like this too affecting fully to express, and having attempted every other method. … I am now sending arms back to Philada. for repairs & beg the Gunsmiths may be daily attended to. I send Major Cox to wait on Council with this letter; do what he can and bring me an account to morrow of the prospect of arms &c.”

In September of 1777, County Lieutenants were becoming desperate to fill their quota of troops while meeting their need for arms, ammunition, and equipment. Almost every county had come up empty when the next class of men were called to service. The County Lieutenant of York wrote to Wharton that “Yesterday I was Hon’d with yr Letter of the 12th Instant & have sent expresses to each Batalion in the County, as to arms we are at a loss for, as the last year the arms was Nearly all taken to Campe, where they mostly remained. The Nonasasiators [Nonassociators], then was mostly disarmed, our situation at present is such, that believe we shant be able to send out many arms….”

And the County Lieutenant of Berks was in a similar predicament. He also wrote to President Wharton after he received orders to call up two more classes of militia to support Washington on September 18, 1777:[24]

“Sir, I rec’d your Excellencies order of the 10th Instant…. for calling out the 3d & 4th Class of ye militia which I’m in hopes will be ready to march soon, but we are badly off for want of arms.”

These County Lieutenants were not alone. The same situation was seen with the militia called up to defend Fort Augusta in Northumberland County along the Susquehanna River. Colonel Samuel Hunter noticed a large amount of Indians nearby that was alarming the population. In his correspondence he indicated that the County was “badly off…for want of arms and ammunition, as I informed Mr. Lowdon off, which is a member of the Council from this County, to endeavor to procure five Hundred stand of arms, which will be very much wanted in case we are invaded here by ye Savages.”[25]

In October, the Board of War issued a proclamation that the arms at Bethlehem (likely those that were acquired during the previous war), were to be confiscated and sent off to militia, though to be used with care:[26]

“Sir, the militia of this state are still in great want of arms, and Council are informed that there are many light ones at Bethlehem which have not stood full proof, which may do in the hands of careful men used to arms. These council request the Board of war will order to be delivered for the militia. You will please to lay this business before the hon’ble Board of war and let me know their answer.”

These issues plagued the militia until 1777–1778,[27] when public stores of guns were filled by supplies shipped from France, but even then it seems as though most of this equipment was used to furnish Continental troops.

Even following the war, after the Federal government had been established, the amount of arms available for the Pennsylvania line and riflemen was staggeringly low. The militia census of 1806 makes note that out of 80,061 privates, 2,881 sergeants, 3,352 riflemen, only 20,000 muskets and 3,352 rifles were on hand—meaning that only 27.1% of the total military force in Pennsylvania were armed.[28]

What does all this mean? The myth that guns were everywhere, and that everyone (or even every household) in Pennsylvania had a gun, has to be put to rest. While such a claim is probably true in certain parts of the country during the Revolutionary War, Pennsylvania holds a unique place in the history of gun culture. It remained a center of conflict for over two decades, and produced large numbers of troops—both Continental and militia—in support of the War for Independence. But proper acquisition, maintenance, and training with firearms just did not catch on. Some claim that the state did not acquire firearms because of the Quaker government, but there were no laws on the books restricting the purchase of guns. And while the Quaker government might not have acquired many firearms for public stores initially, their attitudes changed during the French and Indian War. Nonetheless, their lack of initiative to purchase firearms did not, in any way, infringe upon citizens acquiring them personally. And plenty of gunsmiths and one powder mill existed in Pennsylvania—on the frontier and in towns—so that if one wanted a firearm they could acquire them. Yet for reasons unknown, I cannot say why, Pennsylvanians just did not seem all that interested in acquiring firearms. All I can do is show this in the evidence and let the reader ponder why.

[Featured Image at Top: “The Crossing” by artist Robert Griffing depicting American Indians observing General Braddock’s crossing the Monongahela River; shortly after Braddock would be mortally wounded and most of his men slain. Following his defeat, the French and Indians would move into Eastern Pennsylvania on a campaign of destruction and death without fear of reprisals. Source: Paramount Press, Inc.]

[1] Thomas Verenna, ‘Connecticut Yankees in a Pennamite’s Fort’, Journal of the American Revolution (February 20, 2014).

[2] I recognize that there is no way to avoid dissenters with this subject; regardless of how careful I try to be or how intent I am in supporting my claims, someone will ultimately turn this into a political debate, label me a liberal (or a conservative), and try to force their anachronistic and political bias onto my research. It’s not a matter of ‘if’, but ‘when’. So let me be clear: I’m not arguing against the 2nd Amendment, personal gun ownership, or gun rights—nor am I arguing for them. This article has only to do with evaluating the evidence of gun availability for one colony, in one part of America, in a select amount of time. As the joke goes, Scientist A asks Scientist B, “Have you read the paper on confirmation bias?” Scientist B says, “Yes, but it merely proved what I already knew.” ‘Nuff said.

[3] Bellesiles’ book Arming America: The Origins of a National Gun Culture (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 2000), initially thought to be a landmark on gun culture in America, was widely discredited when it became clear that Bellesiles had fabricated statistics and information in order to fit his conclusions. Despite the unforgiveable and fraudulent activities committed by Bellesiles, the questions that were raised are still interesting and deserve serious academic attention—so long as accurate and authoritative numbers are used to support conclusions and they are reproducible.

[4] James Lindgren and Justin L. Heather, ‘Counting Guns in Early America,’ William and Mary Law Review, Vol. 43, No. 5, (2002), 1777-1842; this is available online in its entirety, accessed March 17, 2014, http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1489&context=wmlr.

[5] ‘Counting Guns’, 1803; Most interesting is that in Southern states, guns were more prevalent (just shy of 60% of the population) while in the middle states we see a lower rate of gun ownership (averaging about 41%). There is some correlation demonstrated in this study between slave ownership and gun ownership—in colonies where slaves were a large portion of the population, private gun ownership rates were over 50%, and if you owned a slave you were 4.3 times more likely to own a gun. Make of that what you will.

[6] See Chart 6, ‘Counting Guns’, 1804. While, admittedly, many of these inventories are incomplete, any guess beyond the written evidence is speculative. Additionally, given the written reports of gunlessness on the frontier and interior counties, I have to believe that whatever increase there might be, had the inventories been complete, it would not make much of a difference.

[7] According to Samuel Hazard, ed., The Register of Pennsylvania, Vol. 5 (Philadelphia: William F. Geddes, 1830), “During all this month [of December 1755] the Indians have been burning and destroying all before them in the county of Northampton, and have already burnt 53 houses there, murdered above 100 persons, and are still continuing their ravages, murders, and devastations, and have actually overrun and laid waste a great part of that country even as far as within 20 miles of Easton, its chief town. And a large body of Indians under the direction of French officers have fixed their headquarters within the borders of that county for the better security of their prisoners and plunder.” (p. 268) See also Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania, Vol. 6, 757-758. For detailed lists of people disbursed, see ‘Powell’s List of Sufferers’ in Publications, Vol. 15 (1906), from the Pennsylvania-German Society which includes facsimiles of the original list of names and a transcription as well—incidentally, several of the names listed are ancestors of mine.

[9] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 2, 450-451. See also James Burd’s letter to his father on the condition of the town, wherein he writes: “this town [Lancaster] is full of People, they being all moving in with their Famillys of 5 or 6 Famillys in a house, we are in a great want of Arms & Ammunition, but with what we have are determined to give the Enemy as Warm a Reception as we Can.” (p. 455) Also Edward Shippen’s letter to Governor Morris a few days later, stating “The People of this County are very willing to join in repelling the Invaders, but are without order, and many want arms.” (p. 463)

[10] James Alexander wrote to Governor Morris about the state of the arms locally in Philadelphia for the Associators, stating, “I can assure you that theres neither arms or ammunition here belonging to the Crown, and it was with great Difficulty that arms were got for the…men, a great part whereof were bought in & brought from Verginea, & the rest brought here and his Ex’y when he went to Albany…” (Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 2, 465). Franklin also wrote to William Parsons at Easton, indicating that these guns were public property (i.e., provincial), “I received also your Letter of the 27th relating the Unhappy Affair at Gnadenhüt, and desiring Arms. I have accordingly procur’d and sent up by a Waggon to one George Overpack’s, A Chest of Arms, containing 50, and 5 Loose, in all 55, of which 25 are for Eastown, and 30 to be dispos’d of to such Persons nearest Danger on the Frontiers, who are without Arms and unable to buy, as yourself, with Messrs. Atkins and Martin may judge most proper: letting all know, that the Arms are only lent, for their Defence; that they belong to the Publick and must be held forthcoming when the Government shall demand them; for which each Man should give his Note.” Benjamin Franklin to William Parsons, 5 December 1755, accessed online March 17, 2014, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-06-02-0126. See also his letter to Parsons on 15 December 1755, accessed online March 17, 2014, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-06-02-0128.

[11] Accessed online, March 17, 2014, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-06-02-0141.

[12] Timothy Horsfield had written to Franklin a month earlier that, “I would also just mention…, that the bearer brings with him some pieces of arms which fail in the using, and which make the people afraid to take them in hand.” (Colonial Records, Vol. 6, 756)

[13] Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 1, Vol. 3, 340 (with chart). For example, the report notes that at Fort Allen, there existed 63 province arms, but only three men had brought their own guns with them. At Fort Henry, there were present 92 province arms, 26 personal guns. And at Fort Hunter, 44 province arms, 3 personal firearms. Not all locations faired this poorly, but those whose companies had a greater number of personal arms were few and far between, and at best the distribution was under 50% personal arms for those locations, notably Fort Swatara and Fort Everit. As with earlier examples, not all the guns were useable. The men stationed at these forts were under-disciplined and did not know how to care for their weapons properly, resulting in guns—both provincial and personal—that could not be counted upon. James Burd noted, during the inspections of the garrisons at Forts Swatara and Hunter that “no province arms fitt for use” due to either neglect or mistreatment. When he arrived at Fort Henry, “ab’t 80 Province arms belonging to these two Comp’ys, good for nothing.” (PA Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 3, 352-353) At Fort William, “no arms fitt for use,…some of them shott tolerable bad, most of their Arms are very bad.” (p. 354) When Burd arrived at Fort Allen, he noted “26 Province Arms bad” and at Fort Lechy, “12 Province Arms bad.” (p. 353) Leaving there he arrived at Peter Doll’s block house (stockade residence) and noted “8 Province Arms bad”, along with 23 “men undisciplined.” (p. 356)

[15] I laid this out briefly in my article in the Journal of the American Revolution, ‘The Darker Side of the Militia’, but thought it better to move these out of the footnotes and into the light.

[16] History of Cumberland and Adams Counties, Pennsylvania (Chicago: Warner, Beers & Co., 1886), 80.

[17] Combined total is from 1790 census numbers from the Counties of Franklin (formerly part of Cumberland during the Revolution), numbering 15,662 people, and Cumberland (per the 1790 borders), with some 18,208 people.

[19] It would have been difficult to hide firearms from Committees of Observation since they kept lists of local residents who owned firearms (in case of such an emergency when their arms would be needed), but by 1777, hoarding guns would be made more difficult and would be an actionable offense; President Wharton directed all County Lieutenants to “make Dilligent search for Musquetts, Carbines, fusees, rifles, & other fire arms, & for swords & Bayonetts, & the same to seize, secure, & deliver to said Lieu’t & his Deputies, or any of them, and it is ordered that if any of said inhabitants shall oppose said search, or conceal any fire-arms, or other weapons afore-mentioned, to apprehend such persons, & take them before one of the Justices of the peace, to be dealt with according to law, and further, the said Lieu’t & his Deputies, are to have all such arms so taken carefully appraised, in order that payment & satisfaction for the same may be made to the rightful owner.” Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 5, 563.

[20] Letter from George Washington to the Council of Safety, December 23, 1776, accessed February 17, 2014:http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0323

[27] In November of 1777, General Irwin writes that he hears of 200 men waiting for arms at Allentown, in Northampton County. He is in such a poor state of arms, which he has arranged to send a large number of “insufficient arms” (old, in need of repair, etc.) to Reading for repair, and from them he planned on supplying the militia at Allentown. The biggest problem he sees is the “villainous practice of thieving guns” by militia on night movements, to which he states, “I could not have imagined the militia capable of.” Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 1, Vol. 5, 656. See also Colonel Morgan’s report from Reading that they had barely any arms and ammunition to supply the troops moving through the town. Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 1, Vol. 5, 756-757.

15 Comments

Two notes that i didn’t add to the draft that support my conclusions further:

1.) Settlers from York petitioned to the Pennsylvania General Assembly in 1755 that ¾ of them were without arms and ammunition and that they are unable to supply themselves with them. (Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 8, Vol. 5, 4096)

2.) William Irvin stated also, in some personal correspondence from York in 1776, that the militia were complaining that “they will in all probability not only be naked at the end of the year but in debt too – & that as soon as the War is at an end the Arms will be useless to them.” (William Irvine to John Hancock, Mar. 23, 1776, Gratz Collection, Generals of the Revolution, case 4, box 12, Historical Society of Pennsylvania) The price of gun ownership at the time was too steep for many of the men, most of whom seemed unable to find a good use for them after the fighting was over. This was indicated in another letter to James Wilson, he stated plainly that “unless something is done or provision made about Arms”, the York County militia would mutiny over the price and cost of guns. (William Irvine to James Wilson, Mar. 23, 1776, in Gratz Collection, Generals of the Revolution, case 4, box 12).

Firearms were also expensive, as well as a cultural oddity to many immigrants. German and Alsatian immigrants had little experience with firearms in their home countries, and the absence of universal militia service in Pennsylvania until 1777 plus pleas for weapons after the 1755 and 1763 Indian attacks demonstrate they were slow to acquire them. (German villagers were often experts at poaching the local prince’s game animals without firearms, and their nets and snares worked just as efficiently in America.) In pre-war 1775 a plain rifle with accoutrements cost roughly six to eight English pounds in Pennsylvania, while a hundred acres of vacant frontier land sold for five pounds, trade guns two to three pounds, military muskets three to four pounds, a horse 10-12 pounds, a piano 20 pounds and a 60’ by 230’ building lot in downtown Allentown 45 pounds . Some sources report significantly different prices and those can be accurate reports, but there were also later wartime runaway inflation, a plethora of currency types and different currency exchange rates between the various colonies to consider. What something “cost” then requires context of place, time and examples as well as comparable currencies (Fogleman 145; Klees 367; Kenneth Roberts; Valuska Thompson’s Rifle Bn 1; Whisker 158).

Well said, Bob!

Great accounting of the situation in Pennsylvania at the time (and the math was actually easy to follow!)

It was certainly a shared experience in New England where the Massachusetts Provincial Congress was similarly faced with a lack of weapons and put out a call for firearms (including bayonets and pikes), their increased manufacture (including marking and proving) of their parts, hiring a master armorer for the province, regulating the work that people were doing in their manufacture, allocating specific numbers of weapons to come from every town for the cause (and which put a hardship on them to fulfill because of scarcity), while the Continental Congress went about creating laboratories, magazines, arsenals in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts.

And then, when weapons were procured (in addition to those arriving from overseas), Washington (on more than one occasion) was faced with such issues as soldiers abusing and wasting those hard-fought resources, thereby forcing regulations to be imposed prohibiting the destruction of government property.

Your article, and the Massachusetts experience (there is more to the story which I plan to flesh out in a future article), affirms that the possession and use of firearms was not as widespread as our current gun-crazed society would want to believe; after all, if there were, then why was so much effort expended in making them available? Good job making that clear as it is a lesson that needs to be repeatedly stated.

Thanks for the comment. I imagine this was definitely a wide spread problem, you’re quite right. But I think that in Southern States the issue was lessened by the fact that they had already developed a ‘gun culture’ (not in the modern sense), especially when it came to the institution of slavery. However the Continental Congress did feel the burning need for firearms early in the war and also realized the problems of allowing disaffected persons to own their own guns, which is why they advocated for completely disarming all Nonassociators in March of 1776. I wrote about this here (though as a warning, this link is a little more political–not by a lot, though):

http://historyandancestry.wordpress.com/2014/04/13/the-first-civil-war-the-revolution-for-americas-soul-part-2/

Southern militias and units probably had higher rates of firearms ownership and a higher percentage of rifles. The ratio of 350 rifles to 1500 muskets confiscated from 2000 Scottish settler households after the 1776 Battle of Moore’s Creek, North Carolina was probably representative.

Yes, Bob, those numbers match the probate records as well. Like I said in the article, you were more likely to own a gun in the South than in the middle colonies.

This is a very interesting article that resonates with research I have done on the First Hunterdon County regiment of New Jersey militia for my book, A People Harassed and Exhausted. I don’t have the mathematical figures such as you found, but I certainly found a number of references to men turning out for duty without weapons. New Jersey militia law from the early colonial period through the Revolution required firearm ownership for men aged 16 to 50 (sometimes 60 during the colonial period) but the law was notoriously not enforced. The law establishing the New Jersey contingent for the Flying Camp in 1776 divided regiments into two divisions and the law came right out and said that when one division went out the unarmed men could be supplied with firearms borrowed from men in the other division. There are also two months from the order book of General Philemon Dickinson – including one of the months right before the Battle of Monmouth – that indicate a number of men who turned out were unarmed. In his orders for early June 1778 he directs captains to send their unarmed men to work on fortifications outside Trenton each day with an officer. At one point there were enough unarmed men that no armed men had to be assigned to this duty, even though Dickinson wanted the work completed rapidly because there was some fear of attack on Trenton from the British troops getting read to leave Philadelphia.

Anyway, thanks for a great article!

Thanks for reading! Glad you enjoyed it! Looking forward to what you have to say about New Jersey.

Good article.

At least in Virginia the Crown provided arms for the militia, and there are numerous letters from county lieutenants stating the number of arms required to complete militia equippage. Lacking proper armories, and to enable rapid response, these arms were kept in the homes of militia members as an adjunct to their militia responsibility. It leads me to believe a couple of facets that may have resulted in “under-counting”. First, since the crown provided arms to militia members, which were passed from antiquarians too old for militia duty to sons or grandsons rising to take over the duty; I wonder how many of those possessing these unnacounted hand-me-down weapons would turn out for crown business bare-handed in order to obtain another issued from the government. Next, since militia-issued arms were Crown-owned, they were not personal property and therefore would not appear in probate records.

I tend to think that these factors lead the “math” to be undercounted to some degree, but wouldn’t hazard a guess as to how substantial. Further, I don’t think that discounts your compelling argument or your conclusion: frontier families were ill-armed at best, and left to find a way to “make do” with what they had.

Good read!

Jim,

Thanks for the comments. Your research suggests that in Virginia, there may have been undercounting in the probate records for sure! However, in Pennsylvania, while undercounting may have occurred, I don’t think it is for the same reasons. All public arms purchased by the crown for use by the militia were left in frontier fortifications (Fort Hunter, Fort Augusta, Fort Allen, etc…). I mention this in note 13 specifically if you’re curious about their condition (no one really knew how to take care of them either which is why Pennsylvania arms collectors have a hard time finding any in decent condition–despite normal wear).

I read somewhere, and for the life of me I can’t find the source any longer (which is driving me insane trying to remember), that American Indian raiding parties would specifically target homes with guns–and local tribes, friendly to white settlers, were often forced at knife-point to relinquish information about local farmers with guns to tribes unfamiliar with the territory–because for a while it was illegal for traders to sell Indians guns and ammunition (particularly after Pontiac’s War). So many farmers didn’t want to risk it. As Bob Smalser pointed out in a comment, hunting without a gun was a trade skill learned by many German immigrants who picked up the craft back in Germany, and that is why so many militia complained about having to acquire the guns for duty themselves (see my first comment above). They didn’t want them in their homes.

Anyway, I would be interested in learning about Virginia’s own arms crisis–if any–and how they handled supplying troops. Might be a worthwhile article to contribute to JAR! Again, thanks for the comment!

I missed #13 – thanks.

I think in Virginia we would find that older, well-found settlements had large stocks of arms maintained in armories. For example the Williamsburg armory was sufficient to outfit four regiments in the span of three weeks when Lord Dunmore fled to “Fowey” in 1775. However, on the frontier the arms were kept in homes. I’m not aware of a public armory in Albemarle County until 1772, even though Charlottesville was well established before then and had a gaol. I’d attribute that to the effect of opening the Shenandoah to settlement about 1725 to 1730. The native people were known to be hostile and there was judicious anticipation they might become more-so once Europeans invalidated the Treaty of Albany’s promise not to expand westward beyond the Blue Ridge. Gov Spotswood offered prize tracts to the Germans and Scotch-Irish he lured into the valley to create what he thought would be a buffer-zone effectively halting raiding parties east of the Blue Ridge. The valley was colonized during a period of hostility. Settlers were forewarned and I suspect fore-armed – I would not be at all surprised if the ratio of arms to settler families was near one. But its a suspicion; the methodology to prove it remains beyond me, which is why I found your article so interesting: perhaps I’m mistaken. Mike Cecere usually has great thoughts on pre-revolutionary Virginia… perhaps we shall collect our thoughts around a stew this weekend

I do look forward to any further discussion on this issue. I am continually amazed at the ratio of arms in different parts of the colonies–as Larry noted above there seems to have been some trouble in New Jersey with acquiring arms too and it would be interesting to see if there were correlating beliefs about guns during that period in the Middle Colonies that, as you point out, may not have existed in Southern Colonies. And it may very well have to do with the types of settlers migrating to these regions. In Pennsylvania too, there is an interesting correlation between gun-totals in areas high in Scotch-Irish immigrants versus areas high in German immigrants. Also in areas where slavery was more normal (in Pennsylvania, slavery was already on the outs before the Revolution had begun–many Germans and Quakers disagreed with the practice).

In either sense, the overwhelming implication is that ‘gun culture’ (again, anachronistic term and I apologize for lack of a better one) was not a stagnant constant throughout the colonies, but one very dependent on specific social and economic factors.

I hope you and Larry publish something on this for the Journal on your respective areas of expertise!

Tom,

Your appeal to for a large perspective and inclusive view is very interesting and I agree that it is something worth pursuing. I have virtually no appreciation for the historiography surrounding gun ownership in the U.S., but would think that some inquiry along the lines you describe would be a worthwhile endeavor. David Hackett Fischer’s Albion Seed: Four British Folkways in America comes to mind as an exemplary effort looking into settlement patterns, mores, etc. from various perspectives that might have some application in such an inquiry.

Gary,

I have to say, I’m really impressed (and quite pleased) with the comments so far. I was certain that I would be getting all kinds of hate for this article (because jerks), but the conversation is going precisely the way I had hoped; it is productive, compelling, and tons of useful information has come to light. This is one of JAR’s greatest strengths; there is this horizontal dialogue happening after a well-researched article and it is something with which most journals cannot compete. Thanks for the heads up on those sources.