Charles Stedman published his two-volume History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War in 1794. For 150 years, the work enjoyed a reputation as a solid, reputable source for the history of the Revolutionary War. Light-Horse Harry Lee, an enthusiastic Patriot, was gracious in his acclaim of the Tory historian. Stedman’s work, he wrote, “was marked by an invariable disposition to record the truth.”[1] Through the first half of the twentieth century, critics praised Stedman’s careful exposition and measured commentary: “Stedman’s History is generally considered the best contemporary account of the Revolution written from the British side.”[2]

Matters changed abruptly in 1958 when R. Kent Newmyer published his article, “Charles Stedman’s History of the American War,” in which he scathed Stedman for systemic plagiarism from the Annual Register.[3] The Annual Register was a London publication, founded in 1758 and popular in the last half of the eighteenth century. Edmund Burke was its first and most famous editor.[4] It contained sections on poetry, book reviews, and science, but for historians, the key section was “The History of Europe,” which published gripping accounts of the war in America. As matters developed, this section may have been too gripping, because it proved the undoing of legions of historians of the war.

Newmyer’s critique had special significance for historians of the southern theater of war. Stedman served as a staff officer to Cornwallis throughout the southern campaign. He encompassed the bulk of the southern war in his volume two, while his membership on Cornwallis’s staff gave his work an additional push of credibility.

Newmyer’s article was part of a long trend of scholarship starting in the late nineteenth century which established that nine histories from the Revolutionary period, formerly believed authoritative, were found lifted wholesale from the Annual Register.[5] Stedman, Newmyer accused, had fallen into the same trap as his contemporaries.

Newmyer’s criticisms fell on fertile ground. After the war, Stedman, a Loyalist no longer welcome in America, took refuge in England, where Cornwallis found him a minor government post. A family acquaintance described Stedman in 1795, “confin’d by ill health, to a retired situation in the country, on a small pension,” all of which “makes it very probable” he turned to writing simply as a means to generate income.[6]

Newmyer focused on the first volume of Stedman’s History. After reviewing the extent of material copied from the Annual Register, Newmyer concluded volume one had only “doubtful value” as a source.[7] A constant problem with volume one was Stedman’s faltering ability to write about matters where he was not present. One prominent example concerned the Battle of Bunker Hill, an engagement he had not witnessed. Stedman insisted the British soldiers at the battle wore knapsacks, adding the oddly specific detail their total equipment load weighed 125 pounds. Stedman was wrong on all counts. The gear weighed much less, and at Bunker Hill, the troops had marched only with weapons and blankets.[8]

Newmyer skimmed briefly over the second volume. He noted that Stedman copied a great deal from Banastre Tarleton’s History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America (London, 1787), some from the Annual Register, but otherwise, he had few comments. Although skeptical, he left open the possibility that the second volume retained some of the value originally ascribed to Stedman’s work.

A review of Newmyer’s criticisms of volume two reveals a great deal. Surprisingly, the problem was not with Stedman, but with Newmyer. Stedman was present throughout the 1780-1781 southern campaigns, and made some observations on his own. Where he relied on outside sources, he used original source materials. The problem arose when the Annual Register relied on the same sources. Newmyer incorrectly ascribed the similarity to Stedman copying the Annual Register. Actually, both Stedman and the Annual Register relied on the same sources, and the similarity reflected their common origin.

Newmyer reserved special criticism for authors parroting the contents of secondary sources, the Annual Register occupying first place on the list. Newmyer branded such works “pseudo histories,” whose value as resources had been destroyed.[9] In writing about the war in the south, Stedman took very little from secondary sources, but relied extensively on primary source documents without attribution. While this earned him proper scorn as a historian, it did not diminish the quality of his history.

Stedman served as commissary officer for General Cornwallis. His position did not place him at the centers of power or decision-making. As a staff officer, though, he had access to the papers from Cornwallis and his subordinate commanders, and was in a position to use all these original materials in crafting his narrative of the southern campaigns.

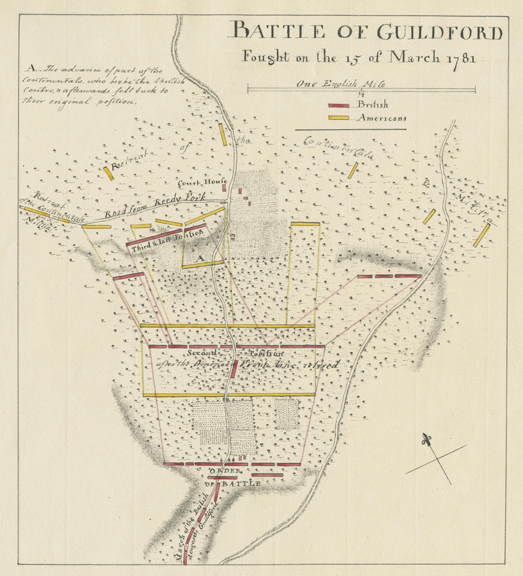

Newmyer used the Battle of Guilford Courthouse to condemn Stedman for plagiarizing the Annual Register. A particularly damning piece of evidence dealt with the attack of the 2nd Battalion, Brigade of Guards against the 2nd Maryland Regiment. This episode provided an ideal vehicle to illustrate the good and bad in Stedman’s work. The Annual Register recorded the event in vivid terms:

Though the enemy were much superior in number, the second battalion of guards, glowing with impatience to signalize themselves, instantly attacked, and routed them with such effect, as to take their cannon; but pursuing them with too much ardour into the wood, they were suddenly thrown into confusion by a very heavy and unexpected fire; and being instantly charged by Col. Washington, at the head of his regiment of dragoons, the disorder was irretrievable, and they were driven back, and pursued into the field, with the loss of the two 6 pounders they had just taken.[10]

Newmyer paid careful attention to the phraseology in Stedman’s work, and commented on its similarity to the wording in the Annual Register. He was correct, and here one cannot miss Stedman’s repetition of unusual terms such as “signalize” and “too much ardour:”

The second battalion of the guards, commanded by the honourable lieutenant-colonel Stuart, was the first that reached the open ground at Guildford Court-house. Impatient to signalize themselves, they immediately attacked a body of continentals, greatly superior in number, that was seen forming on the left of the road, routed them and took their cannon, being two six-pounders; but, pursuing them with too much ardour and impetuosity towards the wood in their rear, were thrown into confusion by a heavy fire received from a body of continentals, who were yet unbroken, and being instantly charged by Washington’s dragoons, were driven back with great slaughter, and the loss of the cannon that had been taken.[11]

Newmyer drew the conclusion that Stedman had simply copied the Annual Register. Given the pervasive plagiarism that infected so many other historians of the period, Newmyer’s conclusion made eminent sense. However, of all the references Newmyer examined in his work, he never suggested Cornwallis as a source. Cornwallis’s reports were readily available to Stedman, as they would have been to the staff of the Annual Register. Cornwallis reported the events of Guilford Courthouse to the government in a letter dated March 17, 1781:

The second battalion of Guards first gained the clear ground near Guildford Court-house and found a corps of Continental infantry, much superior in number, formed in the open field on the left of the road. Glowing with impatience to signalize themselves, they instantly attacked and defeated them, taking two 6-pounders, but, pursuing into the wood with too much ardour, were thrown into confusion by a heavy fire, and immediately charged and driven back into the field by Colonel Washington’s dragoons, with the loss of the 6-pounders they had taken.[12]

Once more, we see the unusual terms “signalize” and “too much ardour,” but in their original context. The language arose out of Cornwallis’s reporting to the government. Newmyer was correct that plagiarism ran rampant in the eighteenth century. He failed to realize the Annual Register was a participant as much as it was a victim.

Stedman, obviously, should have attributed the story of the Guards and the 2nd Maryland to Cornwallis’s report. Quoting or paraphrasing from an official document is a perfectly valid use of an authoritative primary source. His failure to attribute the passage branded him a plagiarist, to be sure, but the reliability of his narrative remained intact. Copying primary sources made his end product good history, just not his own.

At Guilford Courthouse, American general Nathanael Greene formed his men into three lines of battle, and accounts of the engagement have followed Greene’s organization. In discussing the events on the second line, Stedman departed dramatically from Cornwallis. One component of the second line fighting took place far to the American left, where the British 1st Battalion of the Brigade of Guards and the German Regiment von Bose became separated from the main British force, and engaged Lee’s Legion and William Campbell’s riflemen, who had become separated from the main American army. Cornwallis, posted distant from the fight on the extreme British right, reported only that it happened. This is Cornwallis’s account in its entirety:

The excessive thickness of the woods rendered our bayonets of little use, and enabled the broken enemy to make frequent stands with an irregular fire, which occasioned some loss, and to several of the corps great delay, particularly on our right, where the first battalion of the Guards and regiment of Bose were warmly engaged in front, flank, and rear, with some of the enemy that had been routed on the first attack, and with part of the extremity of their left wing, which by the closeness of the woods had been passed unbroken.[13]

The Annual Register copied Cornwallis shamelessly. Note the repetition of the curious locution of the two sides “warmly engaged in front, flank, and rear:”

On the right, the first battalion of guards, with the regiment of Bose, after they imagined that they had nearly carried every thing before them, were warmly engaged in front, flank, and rear, not only with such parts of the routed or broken enemy who had again rallied, but with a part of the extremity of their left wing, which, through the closeness of the wood, had been passed, unbroken and unobserved.[14]

Stedman, on the other hand, detailed the auxiliary second line fighting in several pages of gripping text. He either witnessed the fight, or obtained his information from the men who participated in it. Either way, it departed dramatically from the version in Cornwallis’s report. Stedman, it appeared, when necessary could stand on his own:

At one period of the action the first battalion of the guards was completely broken. It had suffered greatly in ascending a woody height to attack the second line of the Americans, strongly posted upon the top of it . . . Notwithstanding the disadvantage under which the attack was made, the guards reached the summit of the eminence, and put this part of the American line to flight: But no sooner was it done, than another line of the Americans presented itself to view . . . The ranks of the guards had been thinned in ascending the height, and a number of the officers had fallen . . . The enemy’s fire being repeated and continued, and, from the great extent of their line, being poured in not only on the front but flank of the battalion, completed its confusion and disorder.[15]

A review of other engagements in the southern war will emphasize the same points. Stedman wrote partly from his own observations or from evidence taken from other eyewitnesses. Otherwise, he preferred to rely on writings from commanders with personal knowledge of the events about which they wrote. While this serves to liberate Stedman’s reputation from the taint of wholesale copying from a secondary source, it does not relieve him from the taint of plagiarism.

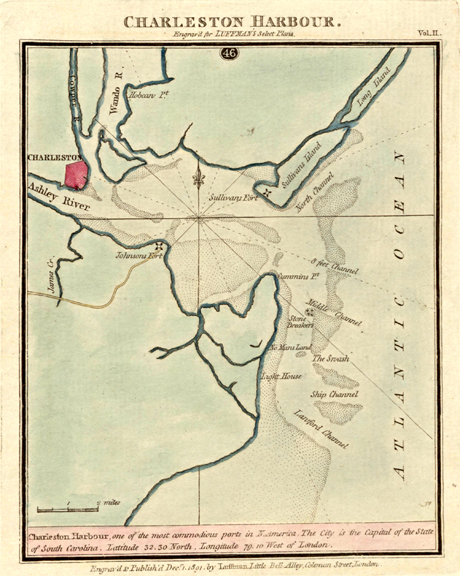

The fighting at Sullivan’s Island provided another example of the paradigm of Stedman’s writing.[16] In June 1776, the government gave Lt. Gen. Henry Clinton 4,600 British regulars and allied him to a massive naval armada. He decided to take the huge force to attack the Patriot fort on Sullivan’s Island in the harbor of Charles Town, South Carolina.[17] The original plan called for a joint ground and naval assault on June 28, 1776. The naval attack degenerated into an orgy of frustration as a day-long bombardment found only embankments of palmetto logs and sand that seemed impervious to cannon fire.

The ground component lay in a different category entirely. The Annual Register described a stillborn military effort, yielding nothing but confusion after the fact: “Such various accounts have been given for the cause of this inaction of the land forces, that it is difficult to form any decided opinion on the subject.”[18] Clinton, conversely, was clear, insisting he had determined a ground attack could not be made as early as June 16. Instead, his role was limited to mounting a “demonstration,” where he kept troops on boats ready to assist the navy should an opportunity arise, but, he lamented, one did not.[19]

Stedman took issue with both accounts, and wrote what he had seen from a warship in the flotilla. He insisted the British light infantry, grenadiers, and 15th Regiment loaded onto boats from the troop transports in the flotilla. The naval gunners provided covering fire for the trip to the army’s landing point on Long Island, separated by seventy-five yards of water from Sullivan’s Island. “Scarcely, however, had the detachment proceeded from Long Island, before they were ordered to disembark, and return to their encampment.”[20] The problem was a trench, previously undiscovered, crossing the width of Sullivan’s Island and within the range of American artillery. This article is not the venue to decide which of the British writers had the best part of the argument.[21] The point here is that Stedman was fully able to part company with other authors and write history on his own.

The Battle of Cowpens provided another example of Stedman’s work. Cowpens represented a signal disaster of British arms such as has been rarely seen through the long path of British military history. On January 17, 1781, Daniel Morgan used massed gunfire to deal a stunning blow to Banastre Tarleton, the most hated and feared British officer in America. Even after such an unprecedented calamity, Cornwallis never lost his faith in Tarleton, and carefully crafted his reporting up the chain of command:

Lt Colonel Tarleton conducted his march so well, and got so near to General Morgan, who was retreating before him, as to make it dangerous for him to pass Broad river, and came up with him at eight o’clock am of the 17th instant. Every thing now bore the most promising aspect. The enemy were drawn up in an open wood, and, having been lately joined by some militia, were more numerous, but the different quality of the corps under Lt Colonel Tarleton’s command, and his great superiority in cavalry, left him no room to doubt of the most brilliant success.[22]

Once more, the Annual Register copied much and added little to Cornwallis’s rendition of events:

Tarleton came up with his enemy at eight in the morning, and nothing could appear more inviting than the prospect before him. They were drawn up on the edge of an open wood without defences; and though their numbers might have been somewhat superior to his own, the quality of the troops was so different as not to admit a doubt of success; which was still farther confirmed by his great superiority in cavalry; so that every thing seemed to indicate a most complete victory.[23]

Stedman, on the other hand, believed Tarleton entirely at fault in creating the disaster. He mercilessly excoriated Tarleton at every opportunity after Cowpens. In one memorable passage, he laid bare his opinions: “Is it possible for the mind to form any other conclusion, than that there was a radical defect, and a want of military knowledge on the part of Colonel Tarleton?[24] In discussing the battle, he paid no obeisance to Cornwallis’s version of events:

Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton, upon receiving the information communicated by the videttes, resolved, without loss of time, to make an attack upon the Americans. Advancing within two hundred and fifty yards of their first line, he made a hasty disposition of his troops . . . This disposition being settled, Tarleton, relying on the valour of his troops, impatient of delay, and too confident of success, led on in person the first line to the attack, even before it was fully formed, and whilst major Newmarsh, who commanded the seventh regiment, was posting his officers.[25]

In discussing Cowpens, Stedman faltered. Ultimately, Cowpens proved his inability to divorce his writing from that of others. Plagiarism, in other words, continued its siren song, and he obeyed. Roderick Mackenzie was an officer who served under Tarleton at Cowpens. Mackenzie was appalled at Tarleton’s unthinking aggression and disregard of sound tactics. His book, published shortly after Tarleton’s memoir, was an impassioned plea against what he saw as Tarleton’s unearned reputation. Stedman, looking to write about Cowpens and needing a source unfavorable to Tarleton, found a kindred soul in Mackenzie. He did not hesitate to borrow from the latter’s work:

Two of their videttes were taken soon after . . . Without the delay of a single moment, and in despite of extreme fatigue, the light-legion infantry and fusileers were ordered to form in line. Before this order was put in execution, and while Major Newmarsh, who commanded the latter corps, was posting his officers, the line, far from complete, was led to the attack by Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton himself.[26]

Stedman’s reliance on Mackenzie was completely reasonable. He believed Tarleton at fault in causing the disaster at Cowpens. Mackenzie was an eyewitness and his narrative was an authoritative primary source. Had Stedman attributed his work, he would have been immune to criticism. But, of course, he did not, and he submitted his History to the world as entirely his own creation.

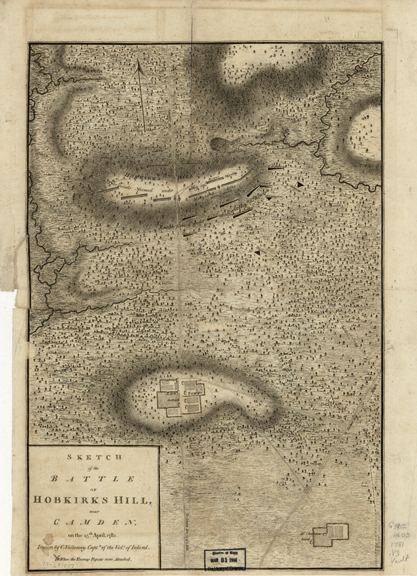

Newmyer criticized Stedman for relying on Tarleton for matters where Tarleton was not a participant, but rather one more in a series of secondary sources.[27] The battle at Hobkirk’s Hill provided an example of the problem. At Hobkirk’s Hill on April 25, 1781, Col. Francis, Lord Rawdon dealt Nathanael Greene another in his series of defeats in the southern war. Neither Tarleton nor Stedman were at Hobkirk’s Hill, both having left for Wilmington with Cornwallis. Rawdon reported his victory to Cornwallis on April 26:

With this force and two six pounders we marched about 10 o’clock yesterday morning, leaving our redoubts to the care of the militia and a few sick soldiers. The enemy were posted upon Hobkirk’s Hill, a very strong ridge, about two miles distant from our front. By filing close to the swamps we got into the wood unperceived and, taking an extensive circuit, came down upon the enemy’s left flank. We were so fortunate in our march that we were not discovered till the flank companies of the Voluntiers of Ireland, which led our column, fell in with the enemy’s picquets. The picquets, tho’ supported, were instantly driven in and followed to their camp.[28]

Tarleton, in what by now is a familiar pattern, copied Rawdon’s report with few changes. One notices in particular his repetition of the specific terms circuit and driving in the pickets:

With this force, and two six-pounders, he boldly marched to attack the assailing army in their camp, in open daylight, at ten o’clock in the morning; committing the redoubts, and every thing at Camden, to the custody of the militia, and a few sick soldiers. The enemy were posted about two miles in front of the British lines, upon a very strong and difficult ridge, called Hobkirk’s hill. By filing close to the swamps on their right, the British columns got into the woods unperceived, and by taking an extensive circuit, came down on the enemy’s left flank, thus depriving them of the principal advantage of their situation. They were so fortunate . . . that they were not in all this course discovered, until the flank companies of the volunteers of Ireland, which led the column, suddenly poured in upon their pickets: These, though supported, were almost suddenly driven in, and pushed to their camp.[29]

Stedman’s text was remarkably similar to both. Given the fact that Tarleton plagiarized the official report, it was rash of Newmyer to assume Stedman copied Tarleton. It was far more likely that Stedman copied Rawdon’s official report, as he had done so often with those of Cornwallis:

Accordingly, at nine in the morning of the twenty-fifth of April, he marched out with all the force he could muster, and by making a circuit, and keeping close to the edge of a swamp, under cover of the woods, happily gained the left flank of the enemy undiscovered. In that quarter the American camp was the most assailable, because there the ascent to the hill was the easiest; but the impenetrable swamp that covered the approach to it had freed the enemy from all apprehension of an attack on that side. In this fancied stated of security, the driving in of the piquets gave them the first alarm of the advance of the British army.[30]

Rawdon faced an enemy while commanding the residue of an army, Cornwallis having taken the bulk of the British maneuver forces with him to Wilmington. To meet this challenge, Rawdon armed everyone in camp. He described his move with a memorable rhetorical flourish: he armed “our musicians, our drummers and in short every thing that could carry a firelock.”[31] Tarleton picked up Rawdon’s phrase, and copied it into his text; Rawdon fielded 900 men “by arming the musicians, drummers, and every thing in the army that was able to carry a firelock.”[32]

Rawdon’s rakish language did not suit the reserved Stedman. Stedman reported stonily that “by arming every person already in the garrison capable of bearing arms, even musicians and drummers,” Rawdon mustered 900 men.[33] Here we see Stedman still copying, but changing words or phrases to conform to his own style. Given the rampant plagiarism in his book, this seems to have been less an effort to disguise his wrongdoing, more a sincere way to present the information in a means he found more palatable. He changed few of Cornwallis’s words, many of Rawdon’s, but his information on Hobkirk’s Hill, drawn directly from Rawdon, was completely accurate. It suffered only from a lack of attribution.

One of the pressing issues in the Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill was the question of whether Rawdon achieved a tactical surprise over Greene. Greene had been awaiting an attack by Rawdon and surprise should have been out of the question. William Johnson, Greene’s first biographer, summarized the scope of the problem: under the circumstances, the charge of surprise was “more disgraceful to a commander than defeat.”[34] Rawdon, writing immediately after the battle and with no idea of the storm coming in Greene’s direction, stated, “the enemy were in much confusion, but, notwithstanding, formed and received us bravely.”[35] Tarleton, writing years after the war and more attuned to the winds blowing across the Atlantic, did not hesitate to join the fray. The American army was “in much visible confusion.”[36] Tarleton continued, leaving no doubt what he felt about Greene’s defensive posture: the American general was “shamefully remiss and inattentive.”

Stedman pulled back from the forward point achieved by Tarleton. Stedman wrote that “the enemy, although apparently surprised, and at first in some confusion, formed with great expedition, and met the attack with resolution and bravery.”[37] Stedman returned the developing narrative of the battle away from invective and back to its roots with Rawdon.

Here, we see the value of Stedman’s work. The praise heaped on Stedman as historian was not for his recitations of dry facts. Stedman earned acclaim for the measured equanimity of his commentary. Lee, for example, complimented Stedman’s “impartiality and respect for truth.”[38] After all, it was Stedman, amid the noise and clamor of the British apologists in the wake of Buford’s Massacre, who had the courage to tell the British public the unpleasant truth that at the Waxhaws, “the virtue of humanity was totally forgot.”[39] His was a principled stand at a time when partisan sentiments bordered on tribalism.

The purpose of this article is neither to punish nor absolve Stedman for plagiarism. He had no excuse for plagiarizing others, even official records, without disclosing the fact to his readers. The question on the table is whether Stedman’s account of the southern war has value as history.

Stedman may be exonerated from Newmyer’s charge that he copied wholesale from secondary sources. Although he copied relentlessly, his preferred sources were authentic, primary materials. He had a strong preference for official reports, and had he simply attributed his work, no one could have found fault. Some of his writing on the southern war derived from his own experience. Much of the rest was taken directly from official reports. Taken together, these factors compel the conclusion that Stedman’s writing on the southern war retains its value as history. Stedman reliably recorded what he saw and what was contained in the reports of commanders in the engagements. Moreover, his commentary drove the value of his history. Stedman, able to see both sides of the war, earned his reputation by explaining both to his readers.

[1] Henry Lee, Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States (Washington, DC, 1827), 25n.

[2] R.W.G. Vail, Elizabeth G. Greene, Marjorie Watkins, Geraldine Beard, Frances Richey, and Edna Watkins, A Dictionary of Books Relating to America from Its Discovery to the Present Time, vol. 23, Spiritual Maxims to Storrs (New York: William Edwin Rudge, 1932−1933), 23:313−314.

[3] R. Kent Newmyer, “Charles Stedman’s History of the American War,” American Historical Review 63(4) (July 1958), 924.

[4] Newmyer asserted Burke retained editorship during the American Revolution, but expert opinion is divided on whether Burke served so long.

[5] E.g., Orrin Grant Libby, “Ramsay as a Plagiarist,” American Historical Review 7(4) (July 1902); William A. Foran, “John Marshall as a Historian,” American Historical Review 43, no. 1 (October 1937). The works included such once-standard references as William Gordon, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment of the Independence of the United States of America, 4 vols. (London, 1788) and David Ramsay, History of the American Revolution, 2 vols. (Philadelphia, 1789).

[6] Ana Maria Clifton to Elizabeth Fergusson, June 27, 1795, in Simon Gratz, “Some Material for a Biography of Mrs. Elizabeth Fergusson, née Graeme,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 29, no. 3 (July 1915), 320.

[7] Newmyer, “Charles Stedman’s History,” 931.

[8] Charles Stedman, History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War, 2 vols. (London, 1794), 1:128. Many problems with Stedman at Bunker Hill are detailed in Don N. Hagist, “Dissecting the Battle of Bunker Hill Painting by Howard Pyle,” Journal of the American Revolution, September 26, 2013, allthingsliberty.com/2013/09/battle-bunker-hill-howard-pyle/.

[9] Newmyer, “Charles Stedman’s History,” 924−925, 931.

[10] Annual Register, or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature, for the Year 1781 (London, 1782), 68.

[11] Stedman, History, 2:340.

[12] Charles Cornwallis to George Germain, March 17, 1781, in Ian Saberton, ed., The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre, 6 vols. (Uckfield, UK: The Naval & Military Press Ltd, 2010), 4:18.

[12] Annual Register … 1781, 55−56.

[13] Cornwallis to Germain, March 17, 1781, in Saberton, The Cornwallis Papers, 4:18.

[14] Annual Register … 1781, 67−68.

[15] Stedman, History, 2:341−342.

[16] An example straying into Stedman’s volume one. Because it relates to the southern conflict, I have included it as an important piece of Stedman’s writing.

[17] Some have posited that Clinton’s naval counterpart, Commodore Peter Parker, made the decision, e.g., John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1997), 5. Stedman placed sole responsibility for the decision on Clinton; Stedman, History, 1:184. In his granular critique of Stedman’s work, Clinton did not object to this assertion. Henry Clinton, Observations on Mr. Stedman’s History of the American War (London, 1794, reprint, New York, 1864), 1−5.

[18] Annual Register, or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature, for the Year 1776 (4th ed., London, 1788), 162.

[19] William B. Willcox, ed., The American Rebellion: Sir Henry Clinton’s Narrative of His Campaigns, 1775–1782, With an Appendix of Original Documents (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954), 34−35; Clinton, Observations on Mr. Stedman’s History, 2.

[20] Stedman, History, 1:186.

[21] Actually, none. The Americans, with greater credibility, uniformly described pitched battles on the beach, none of which appeared in the British accounts. See John Drayton, Memoirs of the American Revolution From its Commencement to the Year 1776, 2 vols. (Charleston, 1821), 2:289; Joseph Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences, Chiefly of the American Revolution in the South: Including Biographical Sketches, Incidents, and Anecdotes, Few of Which Have Been Published, Particularly of Residents in the Upper Country (Charleston, 1851), 95–96.

[22] Cornwallis to Clinton, January 18, 1781, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 3:36.

[23] Annual Register … 1781, 55−56.

[24] Stedman, History, 2:324. The London edition of Stedman contained two pages numbered volume two, page 324. The first in sequence was correct. The second was a misnumbered page 356.

[25] Stedman, History, 2:321.

[26] Roderick Mackenzie, Strictures on Lt. Col. Tarleton’s History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America (London, 1787), 97.

[27] Newmyer, “Charles Stedman’s History,” 931.

[28] Francis Rawdon to Cornwallis, April 26, 1781, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 4:181.

[29] Tarleton, History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America (London, 1787), 478. The ellipsis in the text represented an addition by Tarleton that will be discussed immediately below.

[30] Stedman, History, 2:356 (the misnumbered page actually bearing the number 324).

[31] Rawdon to Cornwallis, April 26, 1781, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 4:181.

[32] Tarleton, History, 478.

[33] Stedman, History, 2:356 (324).

[34] William Johnson, Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene, 2 vols. (Charleston, 1822), 2:72.

[35] Rawdon to Cornwallis, April 26, 1781, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 4:181.

[36] Tarleton, History, 478. This was the language from the ellipsis in the quote mentioned in note 29.

[37] Stedman, History, 2:357.

[38] Lee, Memoirs, 157n.

[39] Stedman, History, 2:193.

7 Comments

Thanks for this excellent and detailed review of the source material. Your painstaking work really gives us a better sense of Stedman and how 18th century historians worked through their process.

Forgive me, but as a “non-scholar” I become somewhat confused in all of this. I know that any direct quotes from another source require that source be identified and that to quote extensively from a third (or fourth or fifth) source without the proper acknowledgement amounts to plagiarism. However, given events (such as battles) in which a fair number of people who know of what they speak may have put their opinions and observations on paper, is it possible to report on these events without, perforce, making mention of what other observers have already written? Again, admittedly, considerable “quotes” require identification of the source, but might not general observations merely encapsulate a number of such observations without the writer being accused of plagiarizing his sources? If that is so, what is the “cut off” between using the observations of other authors that do not require identifying the source(s) and those that do? Thank you.

You are absolutely right that a writer can make general observations without crediting sources. However, Stedman, like many of his contemporaries, was accused of taking another’s work, changing a few words, and presenting it as his own. I like your point that the “cut off” may not be a clear line in some cases. In Stedman’s case, what he did was actually very clear. He made no effort to disguise his copying, and while there may be ambiguity in many books, Stedman’s was not one of them. Thanks for comments.

This article is very well done. Stedman used Colonel John Hamilton of the Royal North Carolina as a source, as the text shows. Stedman is quoted describing Hamilton physically, but I have failed to find that quote in the book.

My question regarding the plagiarism in Stedman’s history would be, “What were the standards for citations in histories in the 1790’s in England”? Were citations widely used and sources documented? By the standards of the time, could Stedman’s accounts be considered plagiarism?

How much of Newmyer’s criticism of Stedman is simply an example of chronological snobbery in applying 20th Century historical academic standards to an author writing over one hundred and fifty years previous? In reading David Crystal’s “Histories of the English Language,” regarding this period in time, citation standards or expectations for authors is in flux and doesn’t appear to be “thoroughly” addressed until later in the Regency Era. This seems supported as well by Macfarlane’s “Original Copy: Plagiarism and Originality in Nineteenth-Century Literature,” and this post by Jack Lynch, https://www.writing-world.com/rights/lynch.shtml , “The Perfectly Acceptable Practice of Literary Theft: Plagiarism, Copyright, and the Eighteenth Century.”

I agree with your point that plagiarism may represent a changing definition over time. We should certainly avoid projecting our standards backwards in time. However, I did not read Newmyer as placing too much emphasis on the idea that Stedman was a “plagiarist” under any definition. I believe he was more concerned with the idea that Stedman copied wholesale from secondary sources. Since Stedman used original sources in dealing with the southern war, much of Newmyer’s fears were groundless. Even so, I think you’re right that Newmyer may have salted his article with some moral judgments based on the standards of his time. Thanks very much for your incisive thoughts. Robert

This is an outstanding investigation into the early historiography. You shine a light on typical historical practices of eighteenth-century scholars and carefully examined source material, exonerating Stedman’s scholarship in the process. Thank you for the contribution.