The Battle of Hobkirk Hill (or Hobkirk’s Hill), sometimes referred to as the Second Battle of Camden, remains one of the less prominent engagements of the Revolutionary War, even as John Buchanan’s masterful study of the campaign in the Deep South terms it “a major and controversial battle” in the American effort to reclaim South Carolina and Georgia from British control.[1] It was fought in the backcountry of South Carolina, just north of the village of Camden, on April 25, 1781, near the site of the first Battle of Camden fought on August 16, 1780. The latter proved to be a humiliating debacle for the insurgent forces in their conflict with Great Britain and especially embarrassing for a disgraced Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, who with the militia fled 180 miles northward to Hillsborough, North Carolina, where he waited for the Continental regulars he had abandoned to show up. On December 3, Gates yielded command of the Southern Department of the Continental Army to thirty-eight-year-old Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, the fifth major general to occupy that position—after Charles Lee, Robert Howe, Benjamin Lincoln, and Gates.

A Peculiar Battle

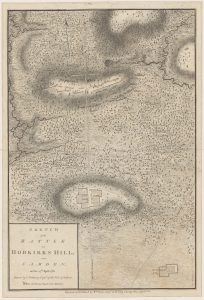

An early twentieth-century account describes Hobkirk Hill, on the crest of which Greene’s troops were posted on the day of the battle, as a narrow sandy ridge about eighty feet in height, not more than a half-mile in length from west to east, above the plain where Camden was situated. Sergeant-Major William Seymour of the Delaware Continental Regiment described this as “a poor barren part of the country,” whose “inhabitants [were] chiefly of a Scotch extraction, living in mean cottages, and are much disaffected, being great enemies to their country.”[2] Tradition held that the hill derived its name from an old man named Hobkirk who lived on the ridge prior to 1781; this appears to be confirmed by a grant in the State Archives of one hundred acres in 1769 to a Thomas Hobkirk in that vicinity.[3]

Following his battle with Lt. Gen. Charles, Earl Cornwallis at Guilford Courthouse, North Carolina, on March 15, 1781, General Greene opted not to pursue Cornwallis’s force that departed the Carolinas to invade their northerly neighbor. Cornwallis was convinced that “Until Virginia is in a manner subdued, our hold of the Carolinas must be difficult if not precarious,” owing to its role as a conduit for supplies to Greene’s army.[4] Rather than follow the fighting earl, Greene reentered South Carolina with the intent of forcing a British withdrawal from their interior outposts to the seaport citadel of Charlestown. Although his army was heavily outnumbered by the nearly eight thousand enemy troops in South Carolina and Georgia, the American commander knew his adversary was scattered among isolated garrisons and thereby stretched exceedingly thin in an effort to maintain the Crown’s authority over a vast area. Greene sought to regain control of as much of South Carolina and Georgia as possible, as expeditiously as possible, and the basis for that strategy stemmed from his anticipation of an Anglo-French peace settlement mediated by other European powers in which each side would retain whatever territory it held when hostilities ended, under the principle of international law known as “uti possidetis” (“as you possess”).[5]

On April 19, Greene’s units took up position on Hobkirk Hill, a mile-and-a-half north of Camden and three miles from the site of the earlier battle. They comprised a total of 1,550 men, and in the coming fight were arrayed as follows: a first line that included, from right to left, the 1st and 2nd Virginia Continental Regiments and the 1st and 2nd Maryland, with the remains of the venerable Delaware Continental Regiment occupying a forward position as pickets when the shooting started; a second or reserve line of North Carolina militia who would not be directly involved in the engagement; the 3rd Continental Dragoons on their left under Col. William Washington (second cousin once removed of the Continental Army’s commander-in-chief), with eighty-seven men but only fifty-six of them mounted[6]; and three 6-pounders posted behind the lines in the center, along the Salisbury Road that cut through the ridge.

In charge of the British outpost at Camden was twenty-six-year-old Col. Francis, Lord Rawdon, to whom Cornwallis had given field command of the royal troops in South Carolina when he chose to head north with the rest of the Crown’s southern army. The colonel’s contingent in the battle included: the British 63rd Regiment of Foot; four Loyalist corps—the New York Volunteers, the King’s American Regiment (also raised in New York), the Volunteers of Ireland (Rawdon’s own regiment), and the South Carolina Royalist Regiment; sixty provincial dragoons; and a company of fifty men called “the Convalescents”—ill or walking wounded able to wield a musket who were summoned from the hospital.[7] “By arming our musicians, our drummers, and in short everything that could carry a firelock,” Rawdon cobbled together a force of some nine hundred, about three-quarters of whom were provincial regulars. He elected to strike the Americans on April 25 before they could attack Camden or be reinforced by a threatened junction with South Carolina militia under Brig. Gen. Francis Marion (known to posterity as the legendary “Swamp Fox”).[8]

The British and Loyalist troops approached their foe’s camp through thick woods and on a narrow front in hope of achieving surprise, and their vanguard struck the opposing picket line on the rebel left at about eleven a.m., when “some [of Greene’s soldiers were] washing their clothes.”[9] The pickets fought well enough that it appears they gave Greene time to muster and deploy his forces. When the two sides were within a hundred yards of each other, the American artillery opened fire with grapeshot and halted Rawdon’s advance. Noting the narrow front of the British column, Greene sought to envelop them on both flanks, but Rawdon quickly brought up his second line and extended his flanks to counter the move. Greene also dispatched Washington’s horsemen to skirt the enemy’s right flank and charge their rear.

As the fighting raged, both Maryland regiments incurred a number of casualties at the hands of Loyalist sharpshooters, losing two estimable officers in Capt. William Beatty of the 1st Maryland and Col. Benjamin Ford of the 2nd Maryland; and at a critical moment, the soldiers of the 1st Maryland—highly regarded veterans who had acquitted themselves admirably at Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse earlier in the year—fell into disorder. Their commander, Col. John Gunby, ordered an abrupt withdrawal in order to reform his unit, but that maneuver adversely impacted other rebel troops as it opened a huge gap in the line and exposed them to flanking fire. Their faltering advance prompted Greene to order a general retreat, and Rawdon’s force surged forward, seeking to capture the three cannon.

With his men pulling back under heavy fire, Greene struggled to rescue the field pieces, even taking hold of the drag ropes himself, until Colonel Washington’s cavalry arrived on the scene and provided protective cover for the retreat. They had ridden around the British right flank and, owing to the topography, were forced to take a circuitous route that put them considerably behind the enemy’s rear, between Logtown—a group of buildings about half a mile north of Camden—and the village itself.[10] As a result, they took scores of prisoners who were not engaged in the battle, rather than striking Rawdon from behind as Greene had directed.[11] Among the captured were three British surgeons who had been ministering to the wounded of both armies, and whom Greene would return upon Rawdon’s request.[12]

The withdrawal of the Continentals and militia left the British and Loyalist troops briefly in possession of the hill, but later that day Washington’s dragoons and the Delaware infantry returned to the battlefield on Greene’s orders to pick up Continental wounded and stragglers, and in so doing drove the British cavalry—whom Rawdon had left behind when he returned to Camden with the rest of his men—back to the village as well.

There has been considerable debate over who was most responsible for the rebel army losing an encounter in which it not only enjoyed a numerical majority of better than three to two but deployed three artillery pieces while the other side had none. In the wake of what he perceived as a defeat snatched from the jaws of victory, Greene indulged his petulant self and sought a scapegoat rather than acknowledge any possible fault in his own tactical decision-making.[13] He accused Colonel Gunby of being “the sole cause of the defeat” and grumbled that

we should have had Lord Rawdon and his whole command prisoners in three minutes, if Col. Gunby had not ordered his regiment to retire; the greater part of which were advancing rapidly at the time they were ordered off. I was almost frantic with vexation at the disappointment . . . [Victory] was certain but for the intervention of one of those incidents which no human foresight can guard against.[14]

A court of inquiry ruled that Gunby’s decision to withdraw and regroup part of his regiment during a general advance was responsible for the outcome; the court nonetheless did not remove him from command.

Some would argue that Greene’s obsessive focus on Gunby minimized other factors contributing to the defeat, such as inept management of the battle by someone of his caliber or an impressive display of field command by the adroit Rawdon.[15] Light Horse Harry Lee (who was not at the battle) attributed Greene’s ill-considered decision to eschew a more defensive, less-risky posture—in particular, detaching Washington’s cavalry from his main body early in the engagement without waiting “until the issue of the battle had begun to unfold itself”—to “unlimited confidence . . . the only instance in Greene’s command, where this general implicitly yielded to its delusive counsel.”[16] And as for Rawdon, credit is due him for having launched a bold assault that took his adversary by surprise and for ably leading his outnumbered force.[17]

Notwithstanding Greene’s chagrin at the outcome, the Battle of Hobkirk Hill stands in stark contrast to the initial clash at Camden eight months before—being a tactical success for His Majesty’s soldiery but a pyrrhic victory nonetheless. Rawdon forced Greene’s army to retreat but left that army intact to renew its campaign. Garret Watts of the North Carolina militia, who was present at both Camden battles, described two very different experiences, noting that in the first there “was no effort to rally, no encouragement to fight” and that “officers and men joined in the flight,” but that at Hobkirk Hill “we had to fight hard and finally were compelled to give way.”[18] Captain Robert Kirkwood of the Delaware Regiment, which was heavily involved in the action, reported that his men retired seven miles from the field of combat.[19] The eyewitness account of Lt. Col. Guilford Dudley, commanding the North Carolina militia battalion, attests to the orderly nature of the withdrawal in the second battle:

Yet at last a retreat became necessary, which was effected with very little loss after we fell back to the foot of the hill, although the enemy pursued our right wing for a mile through the woods, keeping up their fire upon us, whilst our flying troop, in their quarter, were repeatedly rallied by the activity of their officers, faced about, and would pour in volley after volley as the enemy rushed upon us, until we finally gave up the contest.[20]

According to Dudley, Greene’s left wing retreated to Sanders Creek, not quite four miles from Camden, while the right wing met General Greene nearly seven miles from Camden and then “with the general at our head . . . reunited with the left” by the creek at about three or four inthe afternoon. In the meantime, Rawdon buried the dead of both sides on the hill, “affording what relief he could to the wounded in the absence of [the] surgeons brought off by Colonel Washington from the enemy’s rear during the engagement.” The next day, Greene withdrew to a point thirteen miles above Camden and on the 27th, pursuant to a court-martial, ordered the hanging of five men out of a total of twenty or twenty-five deserters captured in the battle.[21]

Repercussions

The two sides at Hobkirk Hill waged what has been described as a classic eighteenth-century battlefield engagement in which the opposing lines exchanged musket fire, at close range and in the open, until one side pulled back.[22] Greene’s casualties were 270 (including 136 missing) and Rawdon’s 258.[23] Estimates vary as to the number killed, wounded, captured, or missing on each side.[24] But the numerical equivalence between the respective aggregate casualty counts belies the disparate impact on the opposing armies. The losses represented about 29 percent of Rawdon’s force versus about 17 percent of Greene’s.

The casualties sustained by the redcoats were substantial enough—along with other actions during this period, including the fall of Fort Watson to an American contingent led by Lt. Col. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee (father of Confederate general Robert E. Lee) and General Marion just two days before—that Rawdon deemed it prudent to abandon his position at Camden and fall back to Monk’s Corner on the Cooper River thirty miles north of Charleston. By abandoning Camden, Rawdon relinquished the key British post in South Carolina, from which ensued significant strategic consequences.[25] Thus began the unraveling of Britain’s tenuous hold over the interior of the state, as one after another of the posts occupied by its regulars or Loyalist units succumbed to the rebels—Fort Granby, Fort Motte, Orangeburg, Fort Galpin, and Georgetown in South Carolina, and Augusta in Georgia.

In that regard, the clash at Hobkirk Hill should be viewed as part of a chain of engagements, sandwiched between two larger and better-known tactical wins by the British in 1781, at Guilford Courthouse in March and Eutaw Springs in September, which yielded them no real benefit and actually undermined their capacity to control the countryside due to the extent of their losses on each occasion. The casualty count from these battles depleted their ranks to the extent that the net effect was, from the standpoint of the Whig enterprise, addition by subtraction.

Greene’s Persistence

As commander of the Continental Army in the South, Nathanael Greene, and the men he led through a litany of battles and sieges in the Carolinas, were nothing if not resilient. “Our wants are without number, and our difficulty without end,” he lamented.[26] Even as they were plagued by a chronic lack of food, clothing, ammunition, horses, forage, and other supplies, and diseases such as malaria and yellow fever that afflicted both sides in the oppressive tropical climate, the hard-pressed rebel soldiery had to contend with the skilled professional military leadership of three opposing battlefield commanders in succession. These included: first, General Cornwallis; then Colonel Rawdon; and finally Lt. Col. Alexander Stewart, who replaced Rawdon when His Lordship returned to England in ill health after the Hobkirk Hill fight.

The resilience displayed by the Continental Army throughout the war, but especially in the South, was fundamental to Britain’s failure to suppress the American rebellion. According to eighteenth-century military protocol, the army that held the field when a battle ended was considered the victor, and by this standard the King’s troops won most of the engagements they fought in North America from 1775 to 1783. Time and again—at Bunker Hill in 1775, Freeman’s Farm in 1777, and the 1781 clashes at Guilford Courthouse, Hobkirk Kill, and Eutaw Springs—the redcoats were indisputably victorious in a narrow tactical sense. Yet each of these confrontations yielded a threefold strategic setback for England: a measurable dent in its limited supply of military manpower, a failure to neutralize the American armies in the field, and a major disappointment when it came to swaying public opinion among its recalcitrant subjects toward the Loyalist point of view or at least convincing them that His Majesty’s forces could not be defeated.[27]

As for Greene’s assessment of the scuffle at Hobkirk Hill, he remarked that “this repulse, if repulse it may be called, will make no alteration in our general plan of operations.”[28] And in words as famous as any ever uttered by an American general, he asserted the resolve of his command to rebound from any such setback, writing to the Chevalier de La Luzerne, Louis XVI’s minister to the United States, three days after the battle: “We fight, get beat, rise and fight again.”[29] This even though the total killed and wounded on this occasion exceeded the number of American soldiers who fell in several more prominent engagements, including Lexington and Concord, Cowpens, King’s Mountain, Princeton, Springfield, Trenton, and the siege at Yorktown.[30] Indeed, the rebel commander might have written of this encounter what he had about the brawl at Guilford Courthouse a month earlier: “We were obligd to give up the ground . . . But the enemy have been so soundly beaten, that they dare not move towards us since the action.”[31]

The British Reaction

Describing the events of April 25 to General Cornwallis—who that same day had begun marching from Wilmington, North Carolina, to Virginia—Lord Rawdon reported that Greene “was strongly posted on Hobkirk’s Hill, just beyond Logtown. After a severe action we routed him totally; his cannon escaped by going off very early, and the enemy’s superiority in cavalry prevented our making many prisoners.”[32] Rawdon’s claim of success was understandable, notwithstanding his vastly inflated estimate of American casualties: “Our action cost us 220 men. Greene lost at the very least 500.”[33]

Cornwallis’s response from his headquarters in Virginia on May 20 proved just as hyperbolic, congratulating Rawdon “on your most glorious victory, by far the most splendid of this war.” At the same time, the general cautioned the colonel that the Crown’s inability to control the South Carolina backcountry, and thereby ensure a secure line of supply and communication from its base of operations in coastal Charlestown—protected by the Royal Navy—to its network of interior posts, suggested the need for Rawdon’s army to pull back: “As to the extensive frontier which we have hitherto endeavored to occupy, I am not certain whether we had not better, relinquish it, even if Greene should move this way [toward Virginia].” Cornwallis implied that prudence would require Rawdon to abandon Camden and its environs: “The perpetual instances of the weakness and treachery of our friends in South Carolina, and the impossibility of getting any military assistance from them, make the possession of any part of the country of very little use, except in supplying provisions for Charleston.”[34]

In fact, the forces of rebellion were on the verge of driving the enemy from every foothold in the Carolinas in the aftermath of Hobkirk Hill, and the supply line of food and forage to the King’s garrison in Camden was being severed by partisan bands led by militia generals Francis Marion, Andrew Pickens, and Thomas Sumter (the latter nicknamed the “Carolina Gamecock”).[35] Their efforts had sustained the revolution in the Carolinas in the face of the British onslaught there in 1780, and their continuing exertions merited the esteem of even a well-known militia critic such as General Greene. He was forced to concede that “the support of the militia is the very ground work of our independence for the regular force can never maintain our cause independent of them.”[36]

On May 9, Colonel Rawdon ordered the evacuation of Camden. His men sent off their baggage, demolished their fortifications, and, as Rawdon advised Cornwallis, “brought off all the sick and wounded excepting about thirty who were too ill to be moved, and for them I left an equal number of Continental prisoners in exchange.” In addition, they “brought off all the stores of any kind of value, destroying the rest,” and “not only the militia who had been with us in Camden but also the well-affected neighbors on our route, together with the wives, children, Negroes and baggage of almost all of them.”[37]

The dour outlook for imperial fortunes was echoed by Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour, commandant at Charlestown, in his letter of May 6 to Maj. Gen. Sir Henry Clinton, who had succeeded Sir William Howe as commander-in-chief of the British army in America three years before. Balfour informed Clinton of the April 25 action, relaying Rawdon’s report of “the victory he gained, though long contested & against superior numbers, especially of cavalry.” However, Balfour added a sober note regarding the dismal prospects for British control of the backcountry, advising Clinton: “But notwithstanding this brilliant success, I must inform your excellency, that the general state of the country is most distressing, that the enemy’s parties are everywhere, the communication, by land, with Savannah no longer exists.” The colonel’s missive noted the imminent threat to the key British outposts at Augusta in Georgia and Ninety Six in South Carolina. In Balfour’s estimation, South Carolina was lost: “Indeed I should betray the duty I owe Your excellency, did I not represent the defection of this province so universal, that I know of no mode short of depopulation, to retain it.”[38]

And finally, Lord Cornwallis reinforced this gloomy message when writing to Clinton from Virginia on May 26:

I am of opinion that it is doubtful whether we can keep the posts in the back parts of South Carolina; and I believe I have stated in former letters, the infinite difficulty of protecting a frontier of 300 miles against a persevering enemy, in a country where we have no water communication, and where few of the inhabitants are active or useful friends.[39]

Perspective

The Battle of Hobkirk Hill involved some 2,400 soldiers. In comparison with eighteenth-century European combat—often featuring encounters in which fifty to one-hundred-thousand men opposed each other—most battles in the American Revolution were quite undersized and some, such as Hobkirk Hill, downright puny. Fewer than a thousand British and Loyalist soldiers fought there, as compared with some twenty thousand Anglo-German troops at the Battle of Long Island in 1776, between nine and fourteen thousand at Brandywine and Germantown in 1777 and Monmouth in 1778, and seven thousand who accompanied Maj. Gen. John Burgoyne’s failed expedition to capture Albany during the Saratoga campaign of 1777. Besides Hobkirk Hill, about a thousand of the King’s soldiers were deployed in the battles at Princeton in 1777, Briar Creek in 1779, and Cowpens in 1781, and in the case of Guilford Courthouse and Eutaw Springs fewer than 2,500. Even though Hobkirk Hill and these other engagements would have been considered mere skirmishes in the context of European warfare at the time, they contributed to the outcome of the American rebellion in a disproportionate manner and portrayed as well as any of the major battles the conduct of the contending armies. That is to say, these affairs shaped the conflict in a way that was far more significant than their size would suggest.[40]

While Hobkirk Hill may never be as famous as Bunker Hill, in both instances the Crown’s forces won what was literally an uphill battle by driving their adversary from the high ground but suffered losses they could ill afford and were left weaker than before. Having been present at both actions and narrowly escaped fatal injury at Bunker Hill, Lord Rawdon would have been well qualified to speak to that.[41] In the end, one might apply Horace Walpole’s observation of General Cornwallis’s performance in the Southern Theater to the other British commanders there as well: they conquered themselves “out of troops.”[42] Those fallen were part of the enormous loss in blood and treasure incurred by the mother country in opposing the rebellion—some forty thousand casualties and fifty million pounds by one account.[43] Parliament’s great orator Edmund Burke, a fierce critic of Britain’s policy toward the American colonies, undoubtedly regarded such a frightful toll as confirming the validity of his remarks to the lower house one month before hostilities erupted at Lexington Common: “Magnanimity in politics is not seldom the truest wisdom; and a great empire and little minds go ill together.”[44]

[1]John Buchanan, The Road to Charleston: Nathanael Greene and the American Revolution (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2019), 84.

[2]William Seymour, “A Journal of the Southern Expedition, 1780-1783,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 7:4 (1883): 380.

[3]Thomas J. Kirkland and Robert M. Kennedy, Historic Camden. Part One: Colonial and Revolutionary (Columbia, SAC: The State Company, 1905. Reprint: Kershaw County Historical Society, 1963-1973), 226.

[4]Charles Cornwallis to Henry Clinton, April 10, 1781, in Sir Henry Clinton, The American Rebellion: Sir Henry Clinton’s Narratives of his Campaigns, 1775-1782, with an Appendix of Original Documents, ed. William B. Wilcox (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1954), 509.

[5]Nathanael Greene to John Mathews, July 18, 1781, in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, ed. Dennis M. Conrad (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 9:38-39. See also John Buchanan,The Road to Charleston: Nathanael Greene and the American Revolution, 191-192.

[6]William Johnson, Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene, Major General of the Armies of the United States in the War of the Revolution (Charleston, SC: A.E. Miller, 1822), 77.

[7]Buchanan, The Road to Charleston, 93.

[8]Francis Rawdon to Charles Cornwallis, April 26, 1781, in The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War, ed. Ian Saberton (Uckfield: Naval and Military Press, 2010), 4:181.

[9]Seymour, “A Journal of the Southern Expedition,” 381.

[11]Patrick K. O’Donnell, Washington’s Immortals: The Untold Story of an Elite Regiment Who Changed the Course of the Revolution (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2016), 336. See also Buchanan, The Road to Charleston, 98-99.

[12]Rawdon to Greene and vice versa, April 26, 1781, in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 8:152, 154, 157.

[13]Terry Golway, Washington’s General: Nathanael Greene and the Triumph of the American Revolution (New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 2006), 269.

[14]Greene to Joseph Reed, August 6, 1781, in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 9:135-136.

[15]Theodore P. Savas and J. David Dameron, A Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution (Eldorado Hills, CA: Savas Beattie LLC, 2013), 296-297.

[16]Henry Lee, Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States (New York: University Publishing Company, 1870), 340. See also Buchanan, The Road to Charleston, 96-97.

[17]Buchanan, The Road to Charleston, 102-103.

[18]Garret Watts, Military Pension Application Narrative, in The Revolution Remembered: Eyewitness Accounts of the War for Independence, ed. John C. Dann (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 195-196.

[19]Robert Kirkwood, The Journal and Order Book of Captain RobertKirkwood of the Delaware Regiment of the Continental Line, ed. Rev. Joseph Brown Turner (Wilmington, DE: The Historical Society of Delaware, 1910. Reprint: Sagwan Press, 2015), 17.

[20]Guilford Dudley, Military Pension Application Narrative, in The Revolution Remembered, 220.

[22]Buchanan, The Road to Charleston, 95.

[23]“Hobkirk Hill: Second Battle of Camden,” American Battlefield Trust, www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/hobkirk-hill. See also The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 8:160n7; and Rawdon, “RETURN of the Killed, Wounded and Missing … April the 25th 1781,” in The Cornwallis Papers, 4:182.

[24]Johnson, in Sketches, 84-85, claims that the “generally conceded” number of casualties included about forty killed and about two hundred wounded and missing on each side, with estimated rebel casualties, based on official and unofficial sources, of eighteen killed, 108 wounded, one hundred captured, and thirty-eight missing. According to Theodore P. Savas and J. David Dameron, in A Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution, 296, casualties among the British/Loyalist troops included thirty-eight killed and 220 wounded and among Continental regulars and militia, eighteen killed and 236 wounded, with an undetermined number captured. O’Donnell, in Washington’s Immortals, 336, cites these figures: Rawdon’s losses — thirty-eight killed, 177 wounded, and 43 missing; and Greene’s losses — eighteen killed, 108 wounded, and 136 missing.

[25]O’Donnell, Washington’s Immortals, 336.

[26]Greene to the Board of War, May 2, 1781, in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 8:189.

[27]Matthew H. Spring, With Zeal and With Bayonets Only: The British Army on Campaign in North America, 1775-1783 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), 279.

[28]George F. Scheer and Hugh F. Rankin, Rebels and Redcoats: The American Revolution Through the Eyes of Those Who Fought and Lived It (New York: Da Capo Press, 1957), 457.

[29]Greene to Chevalier de La Luzerne, April 28, 1781, in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 8:167.

[30]Todd Andrlik, “The 25 Deadliest Battles of the Revolutionary War,” Journal of the American Revolution (May 13, 2014), allthingsliberty.com/2014/05/the-25-deadliest-battles-of-the-revolutionary-war/.

[31]Greene to Reed, March 18, 1781, Teaching American History, teachingamericanhistory.org/document/letter-to-joseph-reed/.

[32]Rawdon to Cornwallis, April 25, 1781, in Charles Cornwallis, Correspondence of Charles, first Marquis Cornwallis, ed. Charles Ross (London: John Murray, 1859), 1:98.

[33]Rawdon to Cornwallis, May 2, 1781, in ibid., 1:98.

[34]Cornwallis to Rawdon, May 20, 1781, in ibid., 1:99.

[35]Christopher L. Ward, The Delaware Continentals, 1776-1783 (Wilmington, DE: The Historical Society of Delaware, 1941), 439.

[36]Greene to Thomas McKean, September 2, 1781, in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 9:278.

[37]Rawdon to Cornwallis, May 24, 1781, in The Cornwallis Papers, 5:288-289.

[38]Nisbet Balfour to Henry Clinton, May 6, 1781, in The Campaign in Virginia, 1781: An Exact Reprint of Six Rare

Pamphlets on the Clinton-Cornwallis Controversy, ed. Benjamin Franklin Stevens (London: 4 Trafalgar Square, Charing Cross, 1888), 1:472-473.

[39]Cornwallis to Clinton, May 26, 1781, in Correspondence of Charles, first Marquis Cornwallis, 1:102.

[40]Spring, With Zeal and With Bayonets Only, 55.

[41]Martin Hunter, The Journal of Gen. Sir Martin Hunter (Edinburgh: Edinburgh Press, 1894), 11.

[42]Horace Walpole to William Mason, June 14, 1781, quoted in Stanley Weintraub, Iron Tears: America’s Battle for Freedom, Britain’s Quagmire, 1775-1783 (New York: Free Press, 2005), 275.

[43]Joseph Ellis, Revolutionary Summer: The Birth of American Independence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013), 178.

[44]“The Speech of Edmund Burke, Esquire, on Moving his Resolutions for Conciliation with the Colonies, March 22d, 1775,” in The American Revolution: Writings from the Pamphlet Debate, ed. Gordon S. Wood (New York: The Library of America, 2015), 2:588.

Recent Articles

That Audacious Paper: Jonathan Lind and Thomas Hutchinson Answer the Declaration of Independence

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Recent Comments

"Eleven Patriot Company Commanders..."

Was William Harris of Culpeper in the Battle of Great Bridge?

"The House at Penny..."

This is very interesting, Katie. I wasn't aware of any skirmishes in...

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...