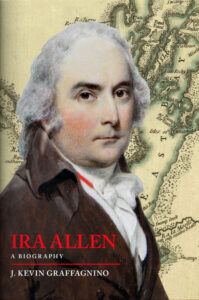

BOOK REVIEW: Ira Allen: A Biography by J. Kevin Graffagnino (Barre, VT: Vermont Historical Society, 2024. $24.95 cloth)

While Ethan Allen’s exploits as the ringleader of the Green Mountain Boys and his 1775 conquest of Fort Ticonderoga are legendary, his youngest brother’s contributions and quixotic schemes are relatively unknown. Kevin J. Graffagnino asserts, in his new book, that Ira Allen was most active and prominent in establishing an independent Vermont government during the American Revolutionary War and continued to pursue various plots to strengthen Vermont’s geopolitical position while scheming to build a land-based commercial empire.

The Vermont scholar’s work is the first Ira Allen biography in almost a century. Graffagnino argues that James L. Wilbur’s 1928 biography is overly hagiographic, necessitating a fresh look at the Vermont founder.[1] At the other end of the spectrum, the author states upfront that he does not like Ira but attempts to present a more balanced view of his life and contributions. While Graffagnino does not esteem Allen, his monograph, based on his 1993 PhD dissertation, represents a lifelong fascination with the man. Further, the author is an expert on Vermont history, having written or edited fifteen of his twenty-five books on the Green Mountain state.

The Vermont scholar’s work is the first Ira Allen biography in almost a century. Graffagnino argues that James L. Wilbur’s 1928 biography is overly hagiographic, necessitating a fresh look at the Vermont founder.[1] At the other end of the spectrum, the author states upfront that he does not like Ira but attempts to present a more balanced view of his life and contributions. While Graffagnino does not esteem Allen, his monograph, based on his 1993 PhD dissertation, represents a lifelong fascination with the man. Further, the author is an expert on Vermont history, having written or edited fifteen of his twenty-five books on the Green Mountain state.

While Ira Allen is not well-known outside Vermont, Graffagnino makes a strong case that he was an important figure in the American Revolution and the Early Republic. He was an early purchaser of land titles granted by the New Hampshire governor (the New Hampshire Grants), which New York authorities legally contested. Ira and his older brothers established the Onion River Company to develop the modern-day Burlington region and the Winooski (Onion) Valley. The Allen clan may have owned 200,000 acres in the New Hampshire Grants. The author points out that several of the company’s transactions appear shady, with Ira bragging about re-selling grants above their values and swindling customers. While the Allen brothers astutely envisioned Burlington’s commercial potential, the venture yielded little long-term profit for the land-speculating family.

During the American Revolution, Ira reached his career apogee, stepping out from his older brother’s shadow. In 1775, the British captured Ethan outside Montreal, and Ethan would not return to the state for almost three years. During his older brother’s absence, Ira grew from “a minor figure to one of the most influential figures in the Grants” (page 112). He was most active in setting up the Vermont government, serving as the state’s surveyor general, treasurer, and Gov. Thomas Chittenden’s confidant. As a troubleshooter, Ira tirelessly traveled the state, putting down outbreaks of residents who supported New York rule. After the Revolution, Ira served as a major general in the Vermont militia, but the rank was primarily ceremonial.

Even in Vermont’s early stages, factions formed, dividing conservative and more democratic politicians. Ira aligned with the latter, including Chittenden and Mathew Lyons. Political opponents included soon-to-be Federalist politicians Issac Tichenor and Nathaniel Chipman. Tichenor, a Vermont legislator, future governor, and United States Senator, became Ira’s archenemy. Tichenor made it a cause-celeb to prevent the final adjudication of Ira’s accounts as treasurer. While the legislature settled a few minor claims, it would have been interesting if the author had expressed an opinion on the validity of Ira’s more substantial claims or Tichenor’s counterclaims. Finally, in anger, Ira challenged Tichenor to a duel, but no affair of honor came to pass (p. 160).

Ira was not content with his political prominence and considerable land holdings, albeit encumbered by substantial debt. Starting in 1780, Ira engaged in one outlandish intrigue after another for the remainder of his life. New York State and the Continental Congress refused to recognize the self-proclaimed Vermont and New Hampshire Grants land titles. As a result, Ethan, Ira, and other senior Vermont politicians exchanged prisoners with the British and entered negotiations for Vermont to rejoin the British Empire. Labeled by historians as the Haldimand Affair, the Continental Congress and many others regarded these murky negotiations as treasonous. However, the true intent is less well-established. Graffagnino believes there is a reason for historians to definitively re-assess the ambiguous Vermont-British talks during the last years of the Revolution (p. xii).

At first, Ira’s post-war intrigues made commercial sense. Lake Champlain flowed north into the Richelieu River and the St Lawrence Valley. He lobbied the British government for trade relations and to build a canal to permit cargo ships’ passage on the Richelieu. The Canadians did eventually create a commercial canal, but not in Ira’s lifetime. After Ira failed to establish trade with Canada, he embarked on a hair-brained plot to create a new nation called United Columbia, linking Vermont, eastern New York, and western New Hampshire with southern Quebec. Ira sailed to France to enlist French support to effectuate such a bold scheme. He obtained 20,000 muskets and a ship to carry the armaments back to Vermont. The British caught wind of Ira’s unrealistic adventure, termed the “Olive Branch Affair,” and intercepted the shipment. As a result, Ira spent a year in British and French jails before being freed. The failed venture further strained Ira’s financial condition. Lastly, Ira even tried to get involved in Spanish-American affairs.

The impractical intrigues were not profitable, further consuming his wealth in Vermont land holdings. Deep in debt, Ira’s Vermont creditors hounded him, and he moved to Philadelphia to escape the debtor’s prison. During the last fifteen years of his life, he lived in poverty, moving among temporary lodgings. His wife, Jerusha, and three children, who barely knew him, remained in Vermont with little direct communication. While his nephew, Heman, managed the few remaining Vermont land titles, his brothers’ descendants sued Ira to recover their families’ share of the Onion River Company assets. There were insufficient unencumbered assets to provide for Ira or the extended family. In 1814, Ira died at age sixty-two as a pauper. Ignominiously buried in an unmarked grave, he remained a pariah among Vermont creditors and estranged from his family. However, his legacy is more complex.

Amidst his intrigues and financial troubles, Ira actively committed to establishing a Burlington-based university, promising a four-thousand-pound lead donation as seed money. He used his diminished political influence to obtain a governmental charter for the University of Vermont. The youngest Allen brother served on the university’s first board of trustees and worked with prominent community members to raise money. He donated fifty acres, valued at a quarter of his original pledge, on a hill overlooking Lake Champlain, on which the main campus of the University of Vermont stands today. While he could not provide the promised additional funding, the University of Vermont recognizes Ira Allen as its founder. His seven-foot bronze likeness sits prominently in the center of the university’s green, donated by his first biographer, James L. Wilbur. While he pursued land speculation and business schemes as a non-graduate, he believed higher education was required to develop Vermont into a thriving society.

Perhaps a purist would prefer that Graffagnino not state his dislike of Ira, as many readers might favor making their judgments. His Allen biography is nonetheless balanced, describing Ira’s contributions and excesses and providing an excellent account of Vermont’s early years. One conclusion that modern Vermonters might quibble with is calling Ira “a hard founding father to love” (p. xxii). Today, the University of Vermont campus tours routinely stop by Ira’s conspicuously located statue and the Ira Allen Chapel to recognize his founding contributions. Additionally, Vermonters named a Green Mountain peak in his honor, Mount Ira Allen, which is visible from the UVM campus. It is the thirty-eighth largest peak out of the 223 named Vermont mountaintops, and, along with the next mountaintop in the range named for his oldest brother, Ethan, it is the only peak commemorating Vermont revolutionaries. No summits are named for Nathaniel Chipman, Issac Tichenor, or any of Ira’s bitter political opponents. Perhaps Vermonters have it right, with Mount Ira Allen only 211 feet lower than the mountaintop named after his oldest brother. Gaffagnino’s biography helps bring Ira out of Ethan’s shadow, appropriately raises his profile, and elucidates his considerable impact on the Revolutionary Era. The author’s insightful narrative demonstrates that not all founding stories are heroic and have happy endings.

This book can be purchased directly from the Vermont Historical Society here.

[1] James Benjamin Wilbur, Ira Allen – Founder of Vermont 1751-1814, 2 vols. (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1928).

Recent Articles

Review: Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City at the American Philosophical Society

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

Recent Comments

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

Sorry I am not familiar with it 2 things I neglected to...

"“Good and Sufficient Testimony:”..."

I was wondering, was an analyzable database ever created? I have been...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

Thank you for bringing real people, places and event to life through...