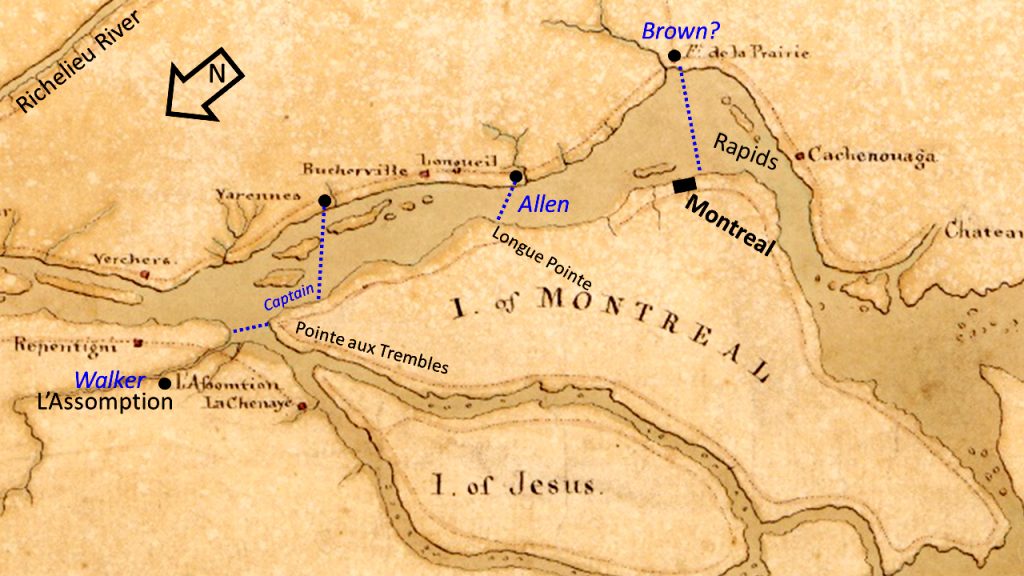

On September 25, 1775, three weeks into the American invasion of Canada, the legendary Ethan Allen fought a fierce battle outside Montreal with about one hundred Canadians and Continental soldiers at his side. The result was bitter defeat at the hands of a larger British-Canadian force that had sortied from the city to confront them at Longue Pointe. The self-penned Narrative of Colonel Ethan Allen’s Captivity claimed that another party was committed to join him in taking Montreal that day, but somehow, he and his men had been inexplicably left to fend for themselves. Over the centuries, historians have had remarkably few primary sources to help unravel this mystery.

Only Ethan Allen’s Narrative, written in 1779, provides substantial details from the American perspective. As a result, historiographical explanations of his misadventure have generally split into two distinct camps. One faction follows dominant contemporary views that Allen’s “imprudence and ambition” had unnecessarily exposed his party to defeat in a rash, uncoordinated attempt on the city, and emphasizes inconsistencies in the self-serving Narrative account[1] Other historians and biographers hew close to the Narrative, focusing on Allen’s claim that Maj. John Brown had committed to a coordinated, supporting attack on Montreal with many more men but did not arrive, leaving Allen to his fate.[2] Long-overlooked Canadian primary sources, however, shed significant light on Allen’s mysterious predicament and suggest an alternative explanation for his “single-handed” battlefield defeat at Longue Pointe on September 25.

An important point in Ethan Allen’s road to Montreal came on July 27, 1775, when he was left without a commission or command after township leaders surprisingly selected Seth Warner to command their new Continental Green Mountain Rangers Regiment. Still eager to contribute to the Patriot cause, Allen joined the September invasion of Canada as a volunteer officer. Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler and Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery focused the Northern Army’s main efforts on a siege of British Fort Saint Johns, just inside the Canadian border, but dispatched the energetic and charismatic Allen on a productive six-day mission behind enemy lines. He served as a liaison with Richelieu Valley Canadian patriots and Indians. Allen returned to headquarters on September 14, and four days later, General Montgomery sent him out once again to promote Canadian partisan recruiting efforts and procure supplies.[3]

Allen ventured down the Richelieu River, north towards the St. Lawrence, and made a last report to Montgomery from St. Ours on September 20. Only the hero’s own Narrative offers an account of his activities thereafter, when he was sidetracked to participate in an attack on Montreal:

On the morning of the 24th day of September, I set out with my guard of about eighty men, from Longueil, to go to La Prairie . . . but had not advanced two miles before I met with Major Brown . . . who desired me to halt, saying that he had something of importance to communicate to me and my confidants; upon which I halted the party, and went into an house, and took a private room with him and several of my associates, where . . . Brown proposed that, “Provided I would return to Longueil, and procure some canoes, so as to cross the river St. Lawrence a little north of Montreal, he would cross it a little to the south of the town, with near two hundred men, as he had boats sufficient; and that we would make ourselves masters of Montreal.”—This plan was readily adopted by me and those in council; and in consequence of which I returned to Longueil[,] collected a few canoes, and added about thirty English Americans to my party, and crossed the river in the night of the 24th, agreeable to the before proposed plan.[4]

To this point, John Brown had been an Allen ally who had joined in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga four months earlier. In the Canadian invasion, Brown was given a similar role to Allen’s, but in a more official role in Canada as a Continental major; he too led remote army missions north of Fort Saint Johns, often in conjunction with the local irregulars.[5] There is no documentary record from Brown or the other participants of this council to verify or contest Allen’s Narrative account of this meeting or the ensuing plans.

In the fateful morning of September 25, Allen anxiously waited to hear the “three huzzas” that Brown’s force would allegedly use to signal a successful crossing from La Prairie and readiness to attack Montreal from the south. After two hours, he concluded that Brown’s force was not arriving. Allen was in a predicament, isolated on the island with just his one hundred men, lacking sufficient watercraft to evacuate the entire force at once. When British and Loyalist forces unexpectedly marched out of Montreal to meet him later that day, he opted for a pitched battle against the odds, until ultimately convinced to surrender.[6]

Sanguinet’s “Eyewitness Account”

As historians have diligently searched for sources that might expand on Allen’s streamlined Narrative, many have overlooked intriguing details in an otherwise well-known Canadian source—the Témoin oculaire, or “eyewitness account” of the 1775-1776 invasion, written by Montreal notary-lawyer Simon Sanguinet and published in French in the nineteenth century. As an active Loyalist and inquisitive government official, Sanguinet was particularly well-informed of events in and around the city. His most enlightening contributions to the Allen story involve pre-battle activities in the dark hours of September 24-25.[7]

While Allen’s Narrative offered just a one-sentence account of that night’s St. Lawrence passage after the party “collected a few canoes,” Sanguinet identified that it was Montreal citizen Jacques Roussain—owner of a canoe service at Allen’s mainland departure point in Longueuil—who “loaned them canoes to facilitate their crossing.” Roussain continued to be intimately involved with the mission that night. He “went, with seven or eight others” to meet the rebel force in Longue Pointe after Allen’s ten o’clock crossing.[8]

Then, Sanguinet’s ‘eyewitness account’ added a particularly intriguing element to the story. “In the course of the night,” Ethan Allen “visited several houses in the Quebec suburb, particularly Jacques Roussain’s.” The Montreal suburbs were known havens for Patriot Canadian activity, and the Quebec (or Sainte-Marie) suburb sat outside the city’s northern walls, closest to Longue Pointe. While Sanguinet did not describe specific topics in Allen’s conversations that night, British sources hint at them. A couple weeks after the battle, Indian Superintendent Guy Johnson recounted that, “relying on some persons said to be disaffected in the City [author’s emphasis], Col: Allen, their most daring partizan, advanced with a body of about 140 Rebels very near Montreal.” Gov. Guy Carleton also related claims from the Canadians captured with Allen, who had said “they expected all the suburbs, some in the town, and many from the neighbouring parishes, would have joined them and that they were to march in without opposition.”[9]

Until events on September 25 proved them wrong, nobody—Loyalist or Patriot—appears to have expected Montreal’s citizens to defend the city if threatened by American forces that week. Continental intelligence reports described British government preparations to evacuate the city, and even erroneously suggested that the governor had already departed. Carleton, too, confided that he believed the city was “defenceless” before Allen’s defeat.[10] The details of overnight discussions from Sanguinet’s journal, combined with widespread assumptions about Montreal’s vulnerability, create a scene in which suburban Patriot friends might have easily convinced Allen that Montreal was ripe for the taking—even with just his own small party. These factors could be construed to support the theory that Allen acted rashly in an attempt to claim victory on his own. On the other hand, these additional elements of the story do nothing to disprove the competing Narrative-aligned theory that Brown negligently or deliberately abandoned Allen to face defeat alone. Sanguinet adds important details, but offers little to solve the core mystery behind Allen’s alleged abandonment.

The L’Assomption Mobilization

Other long-ignored sources—from French Canadian depositions and a priest’s memoirs—describe a substantial effort to cooperate with Allen at Montreal. They make it clear that on the very day of the Battle of Longue Pointe, a Continental captain was deliberately coordinating efforts with Canadian patriot leaders in L’Assomption Parish, twenty-six miles north of Montreal. When integrated into the established story, these accounts complicate the traditional explanations for Allen’s “single-handed” fight.

Early on September 25, Repentigny postmaster Joseph Deschamps brought a carriage to receive two ferry passengers approaching from the north end of the Island of Montreal. He soon met “two strangers, an Acadian, who acted as a French interpreter to the other, who he said was a Bostonian officer wore a blanket overcoat and had a feather in his hat” (French Canadians used the term “Bostonian” to describe Americans from any of the old English colonies). After perhaps an hour’s ride, passing over ten miles of farmland along the L’Assomption River, Deschamps delivered these men at the home of notorious Canadian Patriot Thomas Walker.[11]

Walker had been an outspoken and obnoxious agitator for traditional English rights in Montreal since his arrival from Boston in the early 1760s. As the Revolution brewed, he unsurprisingly took an active role in the city’s Patriot committee of correspondence. In May 1775, partisan tensions flared in Montreal after the controversial Quebec Act went into effect and even more so after rebel Americans raided Fort Saint Johns, so Walker left for his country estate in L’Assomption. There, far from government eyes and Loyalist enemies, Walker kept a covert correspondence with rebel American leaders at Ticonderoga. He provided intelligence and encouraged an invasion of Canada. Even though British authorities intercepted several letters and arrested messengers, they incredibly permitted Walker to remain at liberty, even after the rebel American army entered Canada.[12]

On September 25, Thomas Walker welcomed the visiting Continental captain and interpreter who had been brought to L’Assomption. Walker met with the officer in a separate room for about an hour and a half. The two emerged midway through their discussions to find that six or seven locals had since arrived. Walker purposefully asked them, “is it not true that I have three or four hundred inhabitants at my disposal? to which the said persons replied unanimously, yes sir”—apparently validating claims of support that he had made in private conversation with the captain. L’Assomption’s parish priest, Pierre Huet de la Valinière, later recounted that Walker “had won the confidence of most of the parish & even of many from the surrounding areas.” When the military visitors prepared to leave Walker’s house, the American captain shook hands with all the local guests while the Acadian interpreter told them in French, “come to see us, we will be above Long Point.”[13]

Walker took his rebel guests to visit a Patriot neighbor named Correy, perhaps Edward Correy. Militia captain Jean-Baptiste Bruyère de Belair was at the house and later recounted: “the Bostonian officer, who spoke a little French, said to him: Good-day, Captain, will you do me the favor of inviting your people to come to-morrow with me to look on while I will take the town of Montreal [author’s emphasis].” Belair obliged and left to prepare men for action the next morning.[14]

Traveling on from Correy’s house, the party encountered the parish priests of L’Assomption and neighboring St. Sulpice along the road. The American officer stepped down from the carriage, saluted the clergymen and spoke briefly in English with La Valinière, the “fiery factious and turbulent” L’Assomption priest who was already developing a reputation for being too friendly with Walker’s Patriot faction and the invading rebels. The Continental captain apparently informed La Valinière that Walker had “convinced the Militia captain [Belair] to join his company with the Insurgents & to show up the next day on the very island of Montreal [author’s emphasis].” The carriage driver Deschamps also heard the Acadian tell the priests “we have a hundred men above Long Point [author’s emphasis].” After this, Deschamps took the visitors back to the ferry landing and coordinated their return passage to the Island of Montreal and beyond. Throughout the day, everyone in L’Assomption remained ignorant of the battle already taking place outside Montreal, even though Allen’s Narrative said that he sent a messenger to Walker early that day, beseeching “speedy assistance.”[15]

The following morning, September 26, Thomas Walker and militia captain Belair met near L’Assomption church, prepared to lead their followers to join Allen outside Montreal—still oblivious to his defeat. They found “eighty or one hundred men” assembled for the undertaking. Belair had told them not to bring weapons, so all but three were unarmed—they clearly believed that they would not have to fight to take the city. The L’Assomption men never left their parish that day, though. Allen later reported that Walker disbanded the “considerable number of men” he had raised “upon hearing of my misfortune.”[16]

The Canadian narratives from L’Assomption clearly show that Walker and Belair had assembled nearly one hundred men to join Allen in taking Montreal on September 26, one day after the actual battle outside that city. Postmaster Deschamps also took note of the rebel Acadian interpreter’s repeated references to Ethan Allen’s Longue Pointe landing site, indicating the Continental captain’s familiarity with Allen’s general role in the otherwise nebulous plan to advance into Montreal.

Unfortunately, none of the primary sources identify the name of the Continental captain who made the circuit around L’Assomption that day. His identity might offer new connections to further unravel the mystery behind Allen’s defeat. The most useful distinguishing detail mentioned in the L’Assomption accounts was the visitor’s rank—eliminating the possibility that it was Major Brown or Lieut. Col. Seth Warner. Walker’s visitor was presumably one of a dozen or so American captains ranging north of the Saint Johns siege with diverse, scattered detachments that week, including company commanders from the New Hampshire Rangers, 2nd New York Regiment, and Green Mountain Rangers. It is also noteworthy that Sanguinet mentioned the captain and his interpreter having crossed to the Island of Montreal from Varennes, not from Longue Pointe or Allen’s crossing point at Longueuil, and that they returned on the same path.[17]

A Reconsideration

These long-neglected Canadian sources expand the Battle of Longue Pointe story far beyond the Green Mountain Boys hero’s streamlined Narrative. Although the L’Assomption accounts appear to be disconnected from the Narrative, in combination they suggest a simpler, more practical explanation for Ethan Allen and his hundred men being left to fight on their own outside Montreal. Beyond the traditional “blame Allen” and “blame Brown” camps, it appears that the fog and friction of war were likely at the root of Allen’s alleged abandonment and defeat.

In the week preceding the Battle of Longue Pointe, a handful of dynamic, intrepid but militarily inexperienced American officers were quite busy ranging a 400-square-mile area of operations—a wedge of land defined by Fort Saint Johns, the Richelieu River, the St. Lawrence, and La Prairie. As seen in the chance meeting between Allen and Brown outside Longueuil, these detachment leaders had inconsistent, happenstance communication with each other. Senior commanders had only nominal command and control over these roving operations, with reports arriving at headquarters two or three days after the fact. Even though General Montgomery was aware that his subordinates had been discussing plans for Montreal, time and distance kept him from directly influencing their activities.[18]

It clearly appears that Major Brown, Ethan Allen, and the captains involved in the Montreal scheme failed to properly coordinate key details—the most obvious error being the day for the attack. In contrast to the well-documented L’Assomption mobilization, there are no primary sources that describe Brown making any preparations to cross from La Prairie at that time—suggesting that Allen might also have misunderstood Brown’s promise for support, assuming that it was coming directly from the major’s detachment at La Prairie, when Brown could theoretically have been preparing Walker’s Canadians at L’Assomption instead. The inherent confusion, and perhaps embarrassment, behind such fatally flawed coordination might also explain the remarkable void in the documentary record from any of the other alleged planners. More than one hundred years ago, historian Justin H. Smith thoroughly evaluated many of these same primary sources and rhetorically asked, “Was there a misunderstanding then?” He followed with a similar conclusion: “Apparently there was.”[19]

An anecdote from Ethan Allen’s own Narrative could even be interpreted to support the possibility of a critical coordination error. Describing his subsequent captivity in England, he wrote: “great numbers of people . . . came to the [Pendennis] castle to see the prisoners . . . one of them asked me what my occupation in life had been? I answered him, that in my younger days I had studied divinity, but was a conjurer by profession. He replied that I conjured wrong at the time that I was taken; and I was obliged to own, that I mistook a figure at that time [author’s emphasis], but that I had conjured them out of Ticonderoga.” In the Narrative, Allen represented this as a clever riposte, but it raises the question of what his “mistaken figure” might have been—was it misleading information from his friends in the Montreal suburbs, John Brown’s character and reliability, confusion over the date or other details of the attack, or perhaps really just a witty retort.[20] The failed Montreal operation remains open to interpretation, but Sanguinet’s journal, the L’Assomption depositions, and La Valinière’s memoirs provide important historical elements behind Allen’s unfortunate defeat that should not be ignored in future treatments of the topic.

[1]James Livingston to Richard Montgomery, September 27, 1775, i153 v1 r172 p196, RG360, M247, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), also in Peter Force, ed. American Archives, Fourth Series (AA4)(Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1837-1846), 3: 953; Henry Beekman Livingston to Robert R. Livingston, October 6, 1775, Magazine of American History 21 (1889): 258; Timothy Bedel to Richard Montgomery, September 18 [sic], 1775, i153 v1 r172 p202, RG360, M247, NARA [AA43: 954 transcription with a presumably correct date of September 28]; Benjamin Trumbull, “A Concise Journal or Minutes of the Principal Movements Towards St. John’s . . . in 1775,”Collections of the Connecticut Historical Society 7 (1899): 147; Richard Montgomery to Philip Schuyler, September 27, 1775, Philip Schuyler Papers, New York Public Library [also AA43: 952]; “Extract of a letter from Tionderoga [sic], October 5,” Rivington’s Gazette, October 26, 1775.

[2]Most Ethan Allen and Green Mountain Boy-focused works—especially early ones—follow the thesis that Brown abandoned Allen. In 1798, Ethan’s brother Ira added Seth Warner to this story, essentially accusing both Brown and Warner of deliberate betrayal out of jealousy. Ira Allen, History of the State of Vermont [reprint of The Natural and Political History of the State of Vermont . . . (1798)] (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1969),46. In contrast, the Allen-blaming camp has usually emphasized Brown’s distinguished patriotic military record and proven commitment to the cause to counter the Narrative’s implied claim against him.

[3]Ethan Allen to Philip Schuyler, September 6, 1775, AA43: 742-43; Ethan Allen, Narrative of Col. Ethan Allen’s Captivity (Albany: Pratt and Clark, 1804), 13-15; Schuyler to George Washington, September 20, 1775, AA43: 752; Richard Montgomery to Schuyler, September 19, 1775, AA43: 797; Schuyler to Washington, September 20, 1775, AA43: 752; Trumbull, “Concise Journal,” 145-46.

[4]Allen to Montgomery, September 20, 1775, AA43: 754; Allen, Narrative, 15-16.

[5]John Brown was the major of Easton’s Massachusetts Regiment. He had been very active in Canada in 1775, conducting a fact-finding mission to Montreal in the spring before Ticonderoga, and then conducting several scouting missions across the border to gather intelligence, gage Canadian support, and communicate with Richelieu Valley Patriot cells before the invasion.

[6]Allen, Narrative,15-17. Historian David Bennett offered a detailed critique of the alleged plan described in the Narrative, concluding that Allen’s account is “dubious” and that such a plan would have been “preposterous,” in large part based on the Montreal-area geography. David Bennett, A Few Lawless Vagabonds: Ethan Allen, the Republic of Vermont, and the American Revolution (Havertown, PA: Casemate, 2014), 79-80.

[7]Yves-Jean Tremblay, “Sanguinet, Simon,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sanguinet_simon_4E.html; Justin H. Smith, Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony: Canada and the American Revolution (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907), 1: 387.

[8]Simon Sanguinet, “Témoin Oculaire de l’Invasion du Canada par les Bastonnois: Journal de M. Sanguinet,” in Hospice-Anthelme Verreau, ed., Invasion du Canada: Collection des Mémoires Recueillis et Annotes (Montréal: Eusèbe Senécal, 1873), 49 (author’s translation); Claude Perrault, ed., Montréal en 1781: Déclaration du fief et seigneurie de L’ile de Montréal (Montréal: Payette Radio, 1969),100-1; Alex Jodoin and J. L. Vincent, Histoire de Longueuil et da la Famille Longueuil (Montreal: Gebhardt-Berthiaume, 1889),547.

[9]Sanguinet, “Témoin Oculaire,” 52, 61 (translation from E.B. O’Callaghan Papers, New-York Historical Society, p31); Guy Johnson to Earl of Dartmouth, October 12, 1775, Edmund B. O’Callaghan, ed.,Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New-York (Albany: Weed, Parsons and Company, 1857), 8: 637; Guy Carleton to Earl of Dartmouth, October 25, 1775, Kenneth Davies, ed., Documents of the American Revolution, 1770-1783 (Colonial Office Series), volume 11 (Dublin: Irish University Press, 1976), 165.

[10]“Extract of a letter from a gentleman in Quebeck” September 30, 1775, AA43: 845; Montgomery to Schuyler, September 19, 1775, AA43: 797; Montgomery to Schuyler, September 20, 1775, i153 v1 r172 p184, RG360, M247, NARA; Marie-Thérèse Benoist to François Baby, October 3, 1775, Verreau, Invasion, 317; Allen, Narrative, 18.

[11]Deposition of Joseph Deschamps (Translation), October 10, 1775, Historical Section of the General Staff [Canada], ed., A History of the Organization, Development and Services of the Military and Naval Forces of Canada (Quebec: 1919), 2: 93; Laurent Deschamps, “Deschamps, cultivateurs père et fils,” 14, Atelier d’histoire de Repentigny 2008-2010, www.histoirerepentigny.com/textes-historique.

[12]Lewis H. Thomas, “Walker, Thomas (d. 1788),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walker_thomas_1788_4E.html; “Extract of another Letter from Quebec, dated Oct. 25,” J. Almon, ed., The Remembrancer; or Impartial Repository of Public Events. . . Part 1 (London: 1776), 138.

[13]Deschamps deposition, 93-94;Memoires sur l’état actuel de Canada [la Valinière], MG7 VI, Library and Archives Canada (translation by Teresa Meadows).

[14]Deschamps deposition, 94; “Edouard Curry [Correy],” individual #571003, Programme de recherche en démographie historique, Université de Montréal; Deposition of Jean-Baptiste Bruyères [de Belair] (Translation), October 4, 1775, Historical Section, History, 2: 86-87.

[15]Deschamps deposition, 94; Memoires [la Valinière] (translation by Teresa Meadows); Lucien Lemieux, “Huet de la Valinière, Pierre,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, www.biographi.ca/en/bio/huet_de_la_valiniere_pierre_5E.html; Allen, Narrative, 17. Four years later, Gov. Frederick Haldimand would also describe the troublesome La Valinière as “a perfect rebel in his Heart”; Haldimand to George Germain, October 24, 1779, Add. Mss 21714, fo. 226, Haldimand Papers (Microfilm H-1436), LAC.

[16]Belair deposition, 87; Allen, Narrative, 18; Memoires [la Valinière].

[17]Belair deposition, 87; Deschamps deposition, 94; Memoires [la Valinière]; “Extract of another Letter from Quebec, dated Oct. 25,” Almon, Remembrancer (1776, part 1), 139-40; Sanguinet, “Témoin Oculaire,” 55. The captain who visited L’Assomption was clearly not Ethan’s brother Heman Allen though; he was still waiting to join the campaign after suffering from “the camp disorder” (dysentery); Heman Allen letters, September 16 and October 20, 1775, W18285, pp 37-38, 45-46, RG15, M804, NARA. Circumstantially, the Acadian interpreter was almost certainly Pierre Granger. Deposition of Pierre Charlan, August 6, 1775, Historical Section, History,2: 67; “Pierre Granger,” individual #216625 and family records, Programme de recherche en démographie historique, Université de Montréal.

[18]Montgomery to Schuyler, September 28, 1775 [a.m.], Philip Schuyler Papers, New York Public Library [also AA43: 954].

8 Comments

Has there been any recently published work which has taken into account all of this information concerning the invasion of Canada?

Roland, the most recent comprehensive books on the topic is Gavin K. Watt’s “Poisoned by Lies and Hypocrisy: America’s First Attempt to Bring Liberty to Canada,1775-1776 (2014),” and my book “The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony: America’s War of Liberation in Canada, 1774-1776 (2013).” I also wrote an essay on the campaign in the “The 10 Key Campaigns of the American Revolution (2020).”

A very good published primary source account is Michael Gabriel’s “Quebec During the American Invasion, 1775-1776: The Journal of Francois Baby, Gabriel Taschereau, and Jenkin Williams”–which documents a government fact-finding mission’s conclusions about supporters for both sides. I also have another book, “The Invasion of Canada by the Americans, 1775-1776: As Told through Jean-Baptiste Badeaux’s Three Rivers Journal and New York Captain William Goforth’s Letters.” Hope all of this is helpful.

Mark

I just ordered your book and am looking forward to reading it especially as my ancestry is French-Canadian.

Hi Mark. Your article is an important summary of unknown Canadian accounts of Allen’s Montreal failure. Very interesting. Hope you might write more about the Canadian adventure since no one else seems interested. Thanks for your effort.

Fascinating, thank you for your research. I’m always interested in this period for two reasons: I studied at College Militaire Royal de Saint-Jean, the former Fort Saint-Jean and I’m interested in the events leading to the attack of Québec later that autumn.

Well sourced, very interesting perspective. If confusion was to blame, I would certainly be inclined to lean toward the confusion being intentional. Most reports by formal figures (Montgomery, Washington etc.) immediately blamed Ethan’s ‘ambition’ and laid all blame on him & his ego directly, citing his failure as evidence of their accusation. Then writing of no serious deeper suspicions of others with him. That in itself presents their opinions as more of an effort to smear Ethan’s reputation & paint him as an inept military figure in order to get him out of the picture of any leadership positions. I am definitely one who (at least for now) sees any confusion (very likely as a tactic) being a mechanism of a larger plot against Ethan.

Certainly adds another compelling layer to the mystery of who/what led to his defeat. I really enjoyed this one, Thanks Mark!

Thank you for this reply, Mark I will have to see which of these I can obtain. I never realized how much more there was to the invasion other than the little I learned in school. But then there is only so much time to teach the enormous amount of information which is available. I have picked up two books from the “best 100 ” list for my personal library and I also have all the yearly books put out by the JAR.

Roland

Many thanks for your highly informative account drawing on contemporary sources. It casts further light on Allen’s ‘preposterous’ attack on Montreal.