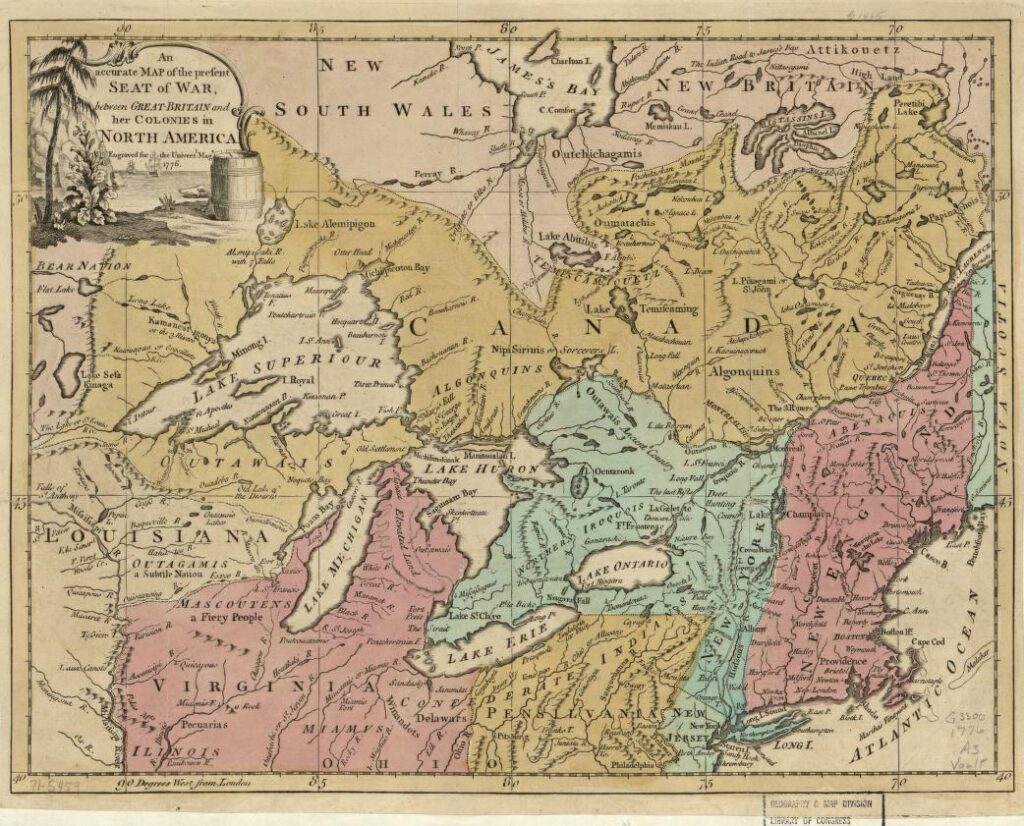

Many followers of the history of the American Revolution are aware of the attempted invasion of Canada by Colonial forces in late 1775. The attack failed, and American designs on Canada were thwarted, for a time anyway. This was not the end of their pursuit to incorporate Canada into the Revolution on the American side. The desire, and planning, to join Canada with the thirteen colonies would ebb and flow throughout the war, peaking several times.

Before the ill-fated 1775 invasion of Quebec, the Continental Congress issued two letters to the inhabitants of Canada; they sent a third in 1776. These letters were for purposes of propaganda to persuade the inhabitants to join the cause. A diplomatic mission to Montreal in early 1776 failed. Even though these efforts were fruitless, the Continental Congress remained so open to incorporating Canada to the new American nation that the Articles of Confederation, drafted in 1777, contained a clause allowing for Canada to join the confederation. Article XI read, “Canada acceding to this confederation, and joining in the measures of the united states, shall be admitted into, and entitled to all the advantages of this union: but no other colony shall be admitted into the same, unless such admission be agreed to by nine states.”[1] On November 29 Congress appointed a committee to translate the Articles into French. [2] Though this was done, there is no evidence that the translated Articles were ever distributed among Canadians.[3]

In January 1778, The Board of War of the Continental Congress decided to step beyond mere propaganda campaigns. It assembled a plan directing that “an irruption be made into Canada, and that the Board of War be authorized to take every necessary measure for the execution of the business.”[4] The Board of War was a new committee of five, set up by Congress, during the struggle for power precipitated by the Conway Cabal. The de facto leader of the Board was Horatio Gates, the newly minted hero of Saratoga who, via the Cabal, was vying with Washington for leadership of the Continental Army. At the height of his influence, some would claim Gates was the dictator of the Board.[5] As such, Washington was cut out of the loop and did not even become aware of the plan until late January.[6] In the end, the Board’s (and Gates’) advocacy for a Canadian invasion may have served as a good argument both for the Board and Gates’ inadequacy in leading the military.

On January 22, 1778, Congress approved the Board’s proposal and the next day “the ballots being taken, major general the Marquis de la Fayette, Major General Conway, and Brigadier General Stark, were elected.”[7] Lafayette was a mere twenty years old, but he knew the political winds. Disregarding Gates’ current ascent, he insisted he would only serve if commissioned under General Washington. Evidencing his support and preference for Washington, Lafayette walked in on a dinner party, in progress, at Gates’ quarters in York, Pennsylvania where Congress was holed up having fled Philadelphia. When asked to offer a final toast, Lafayette “embarrassed Gates,” offering a toast to Washington, then asked to be put under the lead of the Commander-in-Chief rather than the Board of War. [8] In addition, he wanted Johan de Kalb and not Conway as his second officer. To back both demands, he threatened to return to France, taking the other French volunteers with him, and request that the King cut off French aid. With the impending collapse of the Cabal, Lafayette got his way and proceeded to Albany to commence the operation.

Gates curtly informed Washington of the Congress’s vision and plans via a short missive, dated January 24, 1778, simply stating that “By the enclosed Papers your Excellency will see the Designs of Congress in forming the Plan of an Irruption into Canada. Their political Motives for appointing the Officers to conduct the Expedition need not be mentioned, as your Excellency must be struck with the Propriety of the Measure.”[9] Surprisingly, he asked for Washington’s opinion. The general, cannily sensing he was getting involved in a losing proposition, demurred, saying only, “In the present instance, as I neither know the extent of the Objects in view—nor the means to be employed to effect them, It is not in my power to pass any Judgement upon the subject”[10]

On the same day, Gates issued a letter to Lafayette, informing him of his appointment. He also requested that, once he got into Canada, Lafayette gauge the tenor of the Canadian people as to joining the American cause. If they seemed in favor, he should request that they “send Delegates, to represent their State in the Congress of the United States, and to conform in all Political Respects to the Union and Confederation established in them.” If not, then the Americans should “destroy all the works and Vessels at St Johns, Chamblee and the Isle aux noix.”[11]

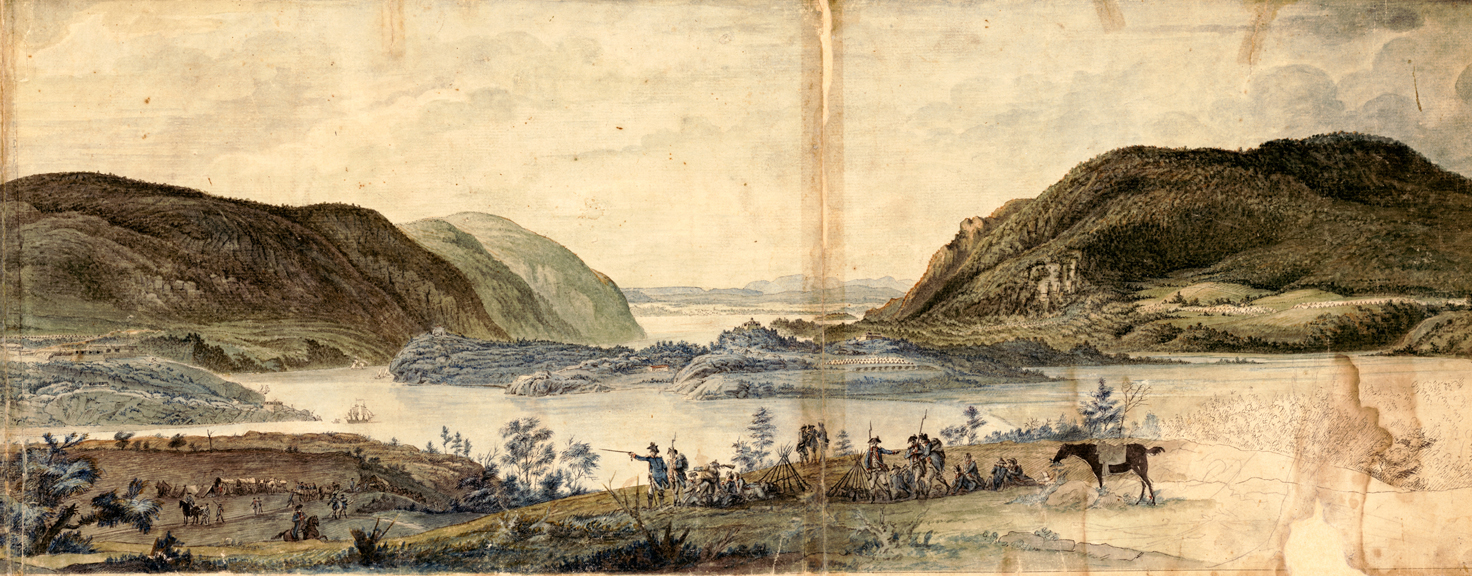

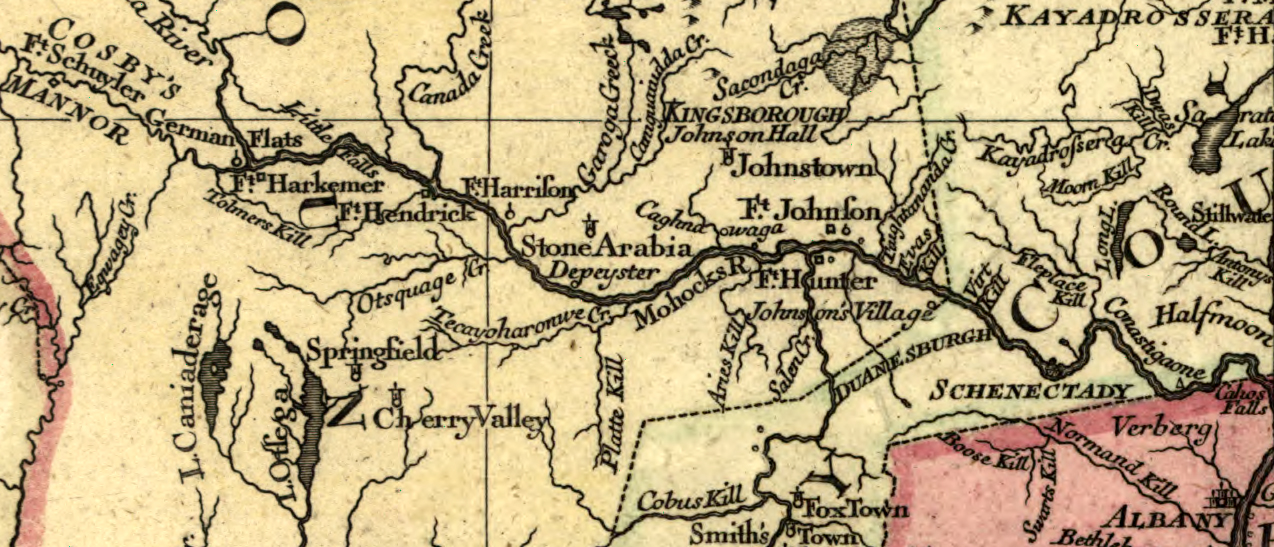

When Lafayette got to Albany, the staging area for the “irruption,” what he found appalled him. Congress had promised him 2,500 men – minimum. He found 1,200 fit for duty, at least in a nominal sense. They were poorly clothed, barely provisioned, on short enlistments, and bottomed out on morale. “I have consulted every body, and every body answers me that I schould be mad to untertake this operation,” he exclaimed.[12] He further observed, “I am sure I will become very ridiculous, and laughed at.”[13] And this seemed to be the consensus. Although they were writing to Conway, not Lafayette, Major Generals Phillip Schuyler, Benjamin Lincoln, and Benedict Arnold all weighed in on the operation with a big thumbs down.

The deeper Lafayette looked into the matter and circumstances, the worse things got. It was time to put this mission out of its misery, and Congress shortly saw the light, taking care to thank Lafayette and his team for their service:

Resolved, That the Board of War instruct the Marquis de la Fayette to suspend for the present the intended irruption, and at the same time, inform him that Congress entertain a high sense of his prudence, activity and zeal, and that they are fully persuaded nothing has, or would have been wanting on his part, or on the part of the officers who accompanied him, to give the expedition the utmost possible effect.[14]

So, the attack on Canada was off the table, but not for long. The seed for the next foray on Canada may have been planted, or at least fertilized, by a seemingly unrelated event. In August 1778, British and French forces tangled at Newport, Rhode Island when French and American land forces also attempted their first real, but unsuccessful, cooperative military operation. After a powerful storm blew in, the British navy fled back to New York. The French landed in Newport but soon repaired to Boston for repairs. The French commander, Comte d’Estaing, was the object of harsh criticism because of the loss and the retreat.

Knowing d’Estaing was smarting from Newport, Lafayette sough to cheer his spirits by writing him a letter with a pep talk. He was writing to give his advice to a naval commander more than twice his age; this took some nerve on his part. In a communication dated August 24, 1778, he dismissed the criticisms of “people who explain away their own stupidities by blaming them on the fleet.” The criticisms didn’t matter anyway, because “offending Mr. Sullivan [the American General at Rhode Island] and the people of New England need not mean falling out with George Washington and Congress, the two great movers of our undertakings.” [15]

He also boldly gave advice to d’Estaing (again, remember the age difference) telling him that “If I were to take the liberty of giving you a bit of advice, it would be to write a long letter to General Washington in which you could slip in a few words of regret about not having cooperated with him.” Then he suggested a new project to help get d’Estaing back in the good graces:

Permit me, Monsieur le Comte, to tell you of a plan that seems to me quite suitable for pleasing Congress in that it allows them a glimpse of some glorious expectations … The Americans will respond to that proposal by saying that we Frenchmen are doing more for ourselves than for them; but if it were possible to soothe them with expectations of a corps of six or ten thousand Frenchmen destined for the conquest of Canada next year, I think Congress would yield[16]

Whether this was the genesis of a new run at Canada or just the continuation of already prevailing thinking is uncertain. Lafayette had surely communicated similar sentiments about attacking Canada again to Congress and to Washington. This all congealed into a much more detailed proposal than the prior one. Congress gave the plan to Lafayette, who was sailing for France in early 1779, to deliver to Benjamin Franklin, the American Ambassador to France. This strategy would need some vetting on the other side of the Atlantic as it incorporated a large contingent of French troops. This strategy was issued by Congress on October 26, 1778, and spelled out detailed military specifics, including a multi-pronged attack on Canada through Detroit and Niagara. Lafayette was returning home to partly because he felt that France should do more, and to lobby Louis XVI for substantial military aid to assist the American cause. The Canada project gave him a concrete proposal to share.

Washington, with the conflicts with Gates behind him for the moment, was again asked his opinion. This time he had plenty to say. He responded with two lengthy memoranda in the form of letters to the President of Congress, Henry Laurens. One analyzed the military aspects of the campaign, and the other offered a more circumspect view of the political nuances, vis a vis the relationship with the French. On the military front, Washington proceeded to dismantle the strategy, starting by saying “It seems to me impolitic to enter into engagements with the Court of France for carrying on a combined operation of any kind, without a moral certainty of being able to fulfil our part, particularly if the first proposal came from us”. He then proved in devastating detail how this was not possible, eventually concluding that “The plan proposed appears to me not only too extensive and beyond our abilities, but too complex. To succeed—it requires such a fortunate coincidence of circumstances, as could hardly be hoped—and cannot be relied on” .[17]

As to the political aspects, Wahington communicated his views in a separate letter to Laurens just three days later. His main fear was that the French, in helping the Americans invade French-Canada, would be a little too at home there. Would the French attempt to hold Canada as their own, in effect restoring Canada to its pre-French and Indian War status? He “fear[ed] this would be too great a temptation to be resisted by any power actuated by the common maxims of national policy.”[18] As much as he respected the French and their contributions to the war, “it is a maxim founded on the universal experience of Mankind, that no Nation is to be trusted farther than it is bound by its interest, And no prudent Statesman or politician will venture to depart from it.”[19]

Unknown to the Americans, there were private discussions among the French that were, ironically, along the same lines and would provide further headwinds for the proposal. One place this came from was Conrad-Alexandre Gerard, who was minister plenipotentiary to the Continental Congress from July 1778 to October 1779. Soon after his arrival in July he found intense interest in a conquest of Canada; on September 24 he wrote that a congressional committee had discussed with him campaigns against Halifax, Quebec, and Newfoundland.[20] In the instructions Gerard was issued before coming to America, he was directed to use all his influence to dampen the American desire for Canada, because the feeling of “uneasiness and anxiety” that would be engendered by the English retention of Canada would be most “useful” in constantly reminding Congress of “their great need for the friendship and alliance” of France.[21] The French government gave no approbation to the project well knowing its motives would be suspected.[22] How much Lafayette was clued into these discussions is unclear, as Gerard had sent a translation of the Franklin plan to French foreign minister Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes on December 21.[23]

Notwithstanding the dialogue between the French policymakers, which, again, was unknown to the Americans but would only have strengthened the case, the twin broadsides from Washington had once again derailed a highly planned effort to take Canada. On January 3, 1779, Congress once again pulled the plug on a Canada adventure. To do so it had to stop Lafayette who, plan in hand, was ready to depart Boston for France to deliver the plan to Frankin. On January 3 John Jay wrote to Lafayette explaining the decision in strictly military terms (leaving out Washington’s political observations). Jay stated, “Prudence . . . dictates that the arms of America should be employed in expelli[n]g the Enemy from her own shores, before the Liberation of a neighbouring Province is undertaken.”[24] Unfortunately, this letter did not reach Lafayette in time, and he boarded the ship Alliance for France on January 11 with instructions in hand. He did not become aware of Jay’s letter and the cancelation of the plan until sometime in May, but back in France Vergennes and company, given the French policy, had short-circuited things anyway.

The combination of Washington’s military and political admonitions and the diplomatic policy of the French expressed through Gerard, which agreed with the American concerns (though for perhaps somewhat different reasons), all served to cool interest in any kind of undertaking to capture Canada. In dismissing the second plan, Congress nonetheless maintained that “every favorable incident be embraced with alacrity to facilitate and hasten the freedom and independence of Canada.”.[25] For the remainder of the war, thoughts of Canada never strayed very far from the minds of American policymakers, and though no substantial moves were made, “American agents hovered on the frontier, agitating the people.”[26] In 1780, Washington had Lafayette, strictly for disinformation purposes, issue several proclamations to the Canadians indicating American and French troops were on the way. In the spring of 1781 a member of Congress, John Sullivan of New Hampshire, proposed an attack on Canada. Washington’s letter dismissing the idea was intercepted and published by the British. These little eruptions kept the British consistently wrongfooted on American intentions, forcing them to remain ever vigilant.

Epilogue

Franklin would make a parlay for Canada’s inclusion in the peace negotiations leading to the Paris agreement of 1783. Congress, in planning for them, instructed Franklin to try to obtain Canada and Nova Scotia in any settlement, if he could. Pursuing these instructions, Franklin in May 1782 suggested to the British representative that, if Britain “should voluntarily offer to give up this province,” it would undoubtedly have “an excellent effect” on the American people. He also attempted to argue that Britain would otherwise be forced to spend a great deal of money to govern and maintain its forces in Canada, which expense would be eliminated by giving it up to the United States. Long story short: the British were not buying what he was selling, and any inclusion of Canada to America in the peace settlement was squelched.[27]

Interest in Canada continued at an exceedingly low ebb even after that. There is just one passing reference to Canada in all extant reports of the proceedings of the Federal Convention of 1787. Unlike with the Articles of Confederatin, there isn’t a single reference, direct or oblique, to Canada in any of the 206 conditions and amendments to the Constitution, which were proposed in the various state ratifying conventions, nor in the voluminous debates themselves. It is apparent that with the ending of the Revolution, the war-inspired fear of Canada waned, and with it the American desire for Canada.[28]

Despite all the maneuverings and plans, when all was said and done, as one source succinctly put it, “When General Montgomery fell mortally wounded in the snows of Quebec, the American cause in Canada, despite the friendly sentiments of the people, was lost.”[29] At least until the War of 1812.

[1] Yale Law School, The Avalon Project – Documents in Law, History, and Diplomacy, Avalon Project – Articles of Confederation : March 1, 1781 (yale.edu)

[2] Carl Berger, Broadsides and Bayonets: The Propaganda War of the American Revolution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017), 43.

[3] Murray G. Lawson, “Canada and the Articles of Confederation,” The American Historical Review, Vol. 58, No. 1 (October 1952), 48.

[4] Journals of the Continental Congress, Thursday, January 22, 1777, www.loc.gov/resource/llscdam.lljc010/?sp=84&st=image.

[5] Justin Harvey Smith, Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony, Canada and the American Revolution (New York: Putnam, 1907), 479.

[6] It was received via a letter from Gates to Washington written January 23, 1778. founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-13-02-0290.

[7] Journals of the Continental Congress, Friday, January 23, 1777, www.loc.gov/resource/llscdam.lljc010/?sp=87&st=image.

[8] George Washington to Horatio Gates, January 27, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-13-02-0317.

[9] Gates to Washington, January 24, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-13-02-0290.

[10] Washington to Gates, January 27, 1978, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-13-02-0317.

[11] Charlemagne Tower, The Marquis de Lafayette in the American Revolution, Volume 1 (Philadelphia: J.D. Lippincott and Company, 1895), 273

[12] Lafayette to Washington, February 19, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-13-02-0505,

[13] Lafayette to Washington, February 23, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-13-02-0552.

[14] Journals of the Continental Congress, Monday March 2, 1778. American Memory – A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774-1875

[15] Stanley J. Izerda, ed., Le Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution – Selected Letters and Papers, 1776-1790: April 10, 1778-March 20, 1780 (New York: Cornell University Press, 1979), 143

[16] Izerda, Le Marquis de Lafayette, 146.

[17] Washington to Henry Laurens, November 11, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-18-02-0103.

[18] Washington to Laurens, November 14, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-18-02-0147.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Izerda, Le Marquis de Lafayette, 192n2.

[21] Lawson, “Canada and the Articles of Confederation,” 52.

[22] “Canada and the American Revolution,” The American Catholic Historical Researches, New Series, Vol. 5, No. 3 (July 1909), 307.

[23] John J. Meng, Despatches and instructions of Conrad Alexandre Gérard, 1778-1780; correspondence of the first French minister to the United States with the Comte de Vergennes (Baltimore: The John’s Hopkins Press, 1939), 349.

[24] John Jay to Lafayette, January 3, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jay/01-01-02-0328.

[25] Lawson, “Canada and the Articles of Confederation,” 50

[26] Berger, Broadsides and Bayonets, 48.

[27] Ibid., 50.

[28] Lawson, “Canada and the Articles of Confederation,” 53-54.

[29] Berger, Broadsides and Bayonets, 51.

3 Comments

Great article, Richard. I’ve long been interested in how serious the attempts to bring Canada into the United States’ fold were, and this is a great, succinct version of the story. I don’t know if you have read it, but if not, I would recommend Lennox Jeffers’ 2022 book “North of America.” It is a good overview of this and other Canadian issues of the era and overall a fast read. Looking forward to your next piece!

Al –

Thanks so much for the kind words. This eternal (it seems) quest for Canada has long been an interest of mine as well, so much so that I’ve thought of writing a book about it. I know a number have already been written, and I’ll definitely order up the book you recommended, but the additional details I found in researching this article tells me that there’s still more to be added to the story. Maybe someday….

Very interesting piece on the invasion of Canada. It was clean and to the point.

I didn’t know the reason behind the invasion.

And to the JAR I read all the articles. The best information.