The General Sir Henry Clinton papers at the William C. Clements Library in Ann Arbor, Michigan, contain a curious document, “A proposal to Subdue the Rebellion and a Sketch of the Necessary Rout for that purpose.” The British military plan envisioned a summer campaign attacking north from New York City to capture the Hudson River and Connecticut River valleys with a force of sixteen thousand soldiers, supported by naval ships and landing craft.[1] Clinton’s principal biographer, William Willcox, does not reference the campaign plan in his authoritative monograph.[2] While historians have thoroughly analyzed Gen. John Burgoyne’s 1777 attempt to capture the Lake Champlain and Hudson River Valleys from Quebec, no historian has interpreted Clinton’s previously overlooked plan.[3] The plan’s obscure nature and London’s strategic shift to counter the French entry into the war have left it unaddressed, to the detriment of better understanding Clinton’s generalship.

At the time of the British planning, Clinton served as second in command to Gen. William Howe. Placing Clinton in charge in New York City, Howe led a tactically successful campaign to capture the Rebel capital city of Philadelphia but failed in the strategically important objective of thoroughly defeating Washington’s army. Clinton’s principal orders were to defend New York City. However, when the New York commander learned of Burgoyne’s distress in the Saratoga region, he led an attacking force up the Hudson River to relieve pressure on Burgoyne and potentially link up with his army at Albany.

Initially, Clinton’s expedition experienced success. He executed a victorious multi-prong attack on Fort Clinton and Fort Montgomery, astride the Popolopen Creek, a few miles south of West Point. His daring, circuitous march to the relatively undefended rear of these forts led to their capture.[4] However, as his command traveled further up the Hudson River, Patriot forces strengthened, and progress slowed. Howe, never keen on supporting Burgoyne’s efforts, ordered Clinton to detach several thousand troops and send them to reinforce the British Philadelphia garrison. As a result, Clinton recalled the attacking regiments to New York City, and his Hudson Valley expedition ended.[5] However, the general’s initial success demonstrated that British forces could sever New England from the other colonies with the proper number of troops and experienced leadership. This experience led General Clinton to believe that the Hudson corridor was the key to winning the war, and either he or a subordinate officer developed a detailed campaign plan to accomplish this objective.[6]

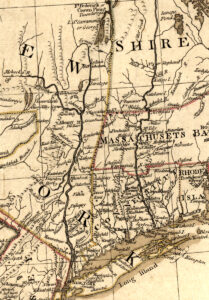

The unsigned and undated twelve-hundred-word plan commences with a two-pronged attack, one up the Connecticut River and the other up the Hudson River. The document calls for an army of ten thousand troops to strike the Connecticut River Valley from Long Island Sound. The objective of this attack was to capture Hartford, Connecticut. The plan is peculiarly silent on the rationale for capturing Harford or any other purposes for this substantial force. However, the planners believed that the region between the Connecticut and Hudson Rivers contained many residents who would side with the King if British troops secured the area.

The campaign’s second prong was to proceed up the Hudson River and recapture Fort Clinton and Fort Montgomery. Next, the British would execute a multi-directional attack to surround and invest the West Point fortress. Leaving a reserve force at Fort Clinton, the remainder of the troops would march to the hills west of West Point to cut off a Rebel retreat. Another group would land on the river’s east side to capture Fort Constitution, located on an island in the Hudson River opposite West Point. A third force would pass West Point’s guns at night to land north of the fort. With all avenues of escape cut off, the British Army would open batteries opposite West Point and bomb the Rebel fortress into submission.

After West Point’s capture, the British would leave four hundred men at Fort Clinton (renamed Fort Vaughan) and an unspecified force opposite West Point to inhibit its reconstitution. Two-thirds of the British army would then march ten miles on the west side of the river to the Rebel post on Butter Hill near New Windsor. The remaining one-third would pass Butter Hill at night on flat boats under the cover of galleys. The amphibious force would land at Martler’s Creek and capture Rebel forces encamped on Butter Hill in concert with the landward force.

Next, the army would march eight or ten miles into the countryside to collect cattle and destroy the “disaffected’s” property. The British author believed this incursion would engender Loyalists to flock to the Royal standard. He would leave eight hundred soldiers to support the gathering of Loyalists. The main army would continue up the river, stopping at Fish Kills to destroy Rebel stores and barracks. The campaign planner envisioned another march into the country to collect supplies, destroy Rebel property, and gather additional Loyalist recruits. The British officer ordered the destruction of all boats to prevent the Rebels from crossing the Hudson.

The British author planned a landward approach to Poughkeepsie by employing a tactic similar to that employed at the Lower Hudson forts. After capturing the town, the British would leave three hundred soldiers and as many Loyalists as needed to establish fortifications. Next, the attacking force would cross the river at Kats Kills and march to Lunenburg. After capturing this town, the water route to Albany would be open, completing the territorial gains envisioned in the campaign plans.

Turning next to defending the newly captured river corridor, the British planner envisioned emboldened Loyalists joining the Royal Army and securing the river as a communications and supply corridor. Couriers would travel the countryside with messages for the Loyalists to assemble at fixed river landings on appointed muster days. The British believed that at least four thousand Americans would enlist under the King’s banner. The author calculated that the British would need only two thousand muskets to properly arm the recruits, as many would bring their own muskets. Army officers would administer oaths of allegiance to pacify the countryside and require two hostages in every district to ensure compliance with their pledges.

Further, all Hudson Valley residents must surrender arms and ammunition and join a Loyalist militia unit. The conscripted soldiers would serve under officers of their choosing to augment Royal forces until the end of the campaign, at most the first of December. In conjunction with the British Navy, the British author planned to station sixty to one-hundred-ton ships in intervals of fifteen to twenty miles between New York City and Albany. The ships would carry supplies and prevent the Rebels from crossing the river, cutting New England off from the rest of the colonies. After achieving the strategic objective of dividing New England from the rest of the rebelling colonies, the war-ending plan abruptly ends.

The two-and-a-quarter-page campaign proposal and accompanying illustrative map are unsigned and undated and not in Clinton’s handwriting but scribed by a British secretary. Despite missing an attribution, the plan to control the Hudson River Valley is consistent with Clinton’s views on winning the war and experiences in the Hudson Highlands. Clinton wrote in his memoirs, I “flattered myself with hopes that I had opened the important door of the Hudson . . . and prevented the rebels from ever shutting it again . . . it would have probably finished the war.”[7] Additionally, the uninscribed plan contains strategies and tactics used by General Clinton during his Fall 1777 Hudson Valley campaign, including waterborne attacks on both sides of the river, attacking rebel forts from the more vulnerable landsides, and using watercraft to more speedily transport troops than the rebels who trod poorly maintained roads through rugged territories.

While the unattributed plan exhibits Clinton’s thinking, other British leaders proposed schemes to capture the Hudson and Connecticut River corridors. Patriot turned Loyalist William Smith wrote a confidential note to Frederick Howard, 5th Earl of Carlisle, who served as a Peace Commissioner, advocating a movement into the region between the Connecticut and Hudson Rivers to rally the purported large number of loyalists in the area.[8] The New York Royal Governor and Major General William Tryon proposed a similar, though more audacious, fast attack plan up the Hudson Valley to capture Albany and enlist the purported many loyalists in the region. While aiming at similar objectives, the Smith and Tryon plans differed in the number of troops, campaign tactics, and methods to punish Rebels. Additionally, Clinton categorically rejected Tryon’s plan as too risky:

He apprehended Mr. Tryon’s Designs were to burn the Villages. He said the proper Mode for conducting the War was to seize the Highland Forts, and make a Lodgment there of 6000 Men, to put 8000 more on the coast of Connecticut, and act by Detachments from New York and Rhode Island in a variety of Occasional Descents favoring the main Bodies.[9]

Therefore, Clinton or a member of his staff is the most likely author of the Clements Library document (“Clinton Plan”) and not Governor Tryon or Jurist William Smith. Furthermore, Clinton thought enough of the plan to retain a copy among his papers.[10]

Similarly, one can infer that Clinton drafted the plan, or ordered it drafted, after October 1777, as the Clinton Plan refers to Fort Vaughan, which he renamed from Fort Clinton after its capture on October 6, 1777. The document provides another hint as to its preparation time by specifying the initiation of the Hudson and Connecticut Valley campaigns before May. After achieving success in the fall of 1777, the British could have developed the attack plan before the 1778 summer campaign season. However, it is less likely that the British developed the plan in 1778 – that year, Clinton focused on a compelling defense of the vital New York City while the bulk of Howe’s command garrisoned Philadelphia. In late 1777, the British commander worried more about protecting New York City and its critical harbor. Clinton assessed in his memoirs that his forces were “too low to admit of more than the strictest defensive (6142 rank and file fit for duty).”[11]

On March 8, 1778, Lord George Germain appointed Clinton as successor commander-in-chief to Howe. Accompanying his orders, Germain assumed responsibility for deploying British North American forces to reflect France’s entry into the war. The American Secretary ordered Clinton to abandon Philadelphia, freeing up troops for the West Indies, St. Augustine, and Pensacola garrisons, and offensive operations in the Southern Colonies. Germain issued discretionary orders for Clinton to raid the New England coast to destroy privateers and cut off supplies for Washington’s army.[12]

Despite his superior’s focus elsewhere, Clinton continued to see offensive opportunities in the Hudson Valley before the 1779 summer campaign season. The British general asserted,

And, when the attention of the enemy should by these operations be turned to the southward, it was planned that the armament should suddenly return and join in a move I proposed up the North River against the rebel forts that covered King’s Ferry. And, should the English and West Indies reinforcements join me at that critical moment (as was promised and fully depended on), it was my intention to extend my views even to the attacking the works at West Point.[13]

While Clinton did not receive sufficient forces to conduct a full-scale attack up the Hudson Valley, he did attack as far north as Stony Point in an attempt to recapture a portion of Burgoyne’s convention troops transiting the river on their way to prisoner-of-war camps in Virginia. This attempt failed due to arriving late at the crossing point. However, Clinton established a post at Stony Point, which Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne famously seized on July 16, 1779. After this defeat, Clinton continued to look for ways, such as Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold’s treason, to capture West Point. Eventually, Clinton gave up on a Hudson Valley operation due to the lack of forces and explicit orders to focus efforts on the southern theater.

While nothing came of Clinton’s projected Hudson Valley campaign, the plan’s existence demonstrated that Clinton sought promising, aggressive offensive opportunities. Due to more significant geopolitical issues, he did not possess sufficient latitude to resource and execute his plans. By the time of Clinton’s appointment as commander in chief, war planning necessarily shifted to London due to the French entry into the war. Given the need to confront French forces globally, Lord Germain relegated Clinton to a tactical commander in the former thirteen colonies with fewer resources and vague and discretionary orders. Given that all strategic plans emanated from London, Clinton never sent any plan to Lord Germain, unlike William Howe, who bombarded his superiors with four military alternatives to end the war over five months.[14]

Although the “Clinton Plan” demonstrated considerable local knowledge and military insights, it was not sufficiently complete to execute successfully. The plan offered copious details on the Hudson River attack vector and none on the Connecticut River grouping, resulting in several unaddressed questions. Why deploy a larger force on the Connecticut River? What objectives were to be accomplished in this region? Additionally, the plan does not address contingencies such as a counter-attack from Washington’s main army. Finally, General Wayne’s daring nighttime attack and successful capture of the Stony Point fortress demonstrate that accomplishing “Clinton’s Plan’s” objectives might be easier than holding them.[15]

The Clinton Plan belies the commonly held view by contemporaries and some historians that Clinton was overly passive and unaggressive.[16] Its existence demonstrates that Clinton was a skillful strategist who developed a workable strategy to end the war, informed by his perceptive, unmatched on-the-ground experiences.[17] The “Clinton Plan” represented early thinking of what the British commander would have done if he possessed sufficient war planning latitude from London and was provided with adequate resources. Finally, the plan’s existence gives credibility to Washington’s focus on controlling the Hudson Highlands and keeping its river crossing open to transit soldiers and supplies.

[1]Henry Clinton, “A Proposal to Subdue the Rebellion and a Sketch of the Necessary Rout for That Purpose” (August 1777), Henry Clinton Papers Volume 29, Folio 13, William C. Clements Library.

[2]William B. Willcox, Portrait of a General: Sir Henry Clinton in the War of Independence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1964).

[3]The most recent account of General Burgoyne’s 1777 invasion is Kevin John Weddle, The Compleat Victory: The Battle of Saratoga and the American Revolution (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2021). Another excellent account is Dean R. Snow, 1777: Tipping Point at Saratoga (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[4]For the most detailed account of the Fort Montgomery and Fort Clinton battles, see William H. Carr and Richard J. Koke, “Twin Forts of the Popolopen – Forts Clinton and Montgomery, New York, 1775-1777,” Bear Mountain Trailside Museums 1, republished October 2006 (July 1937).

[5]Henry Clinton, The American Rebellion Sir Henry Clinton’s Narrative of His Campaigns, 1775-1782 with an Appendix of Original Documents, ed. William D Wilcox (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954), 81.

[6]Clinton, The American Rebellion, 81.

[8]William Smith, Historical Memoirs of William Smith, 1778-1783, ed. William H. W. Sabine (New York: New York Times & Arno Press, 1971), 43–44.

[9]Henry Clinton quoted in ibid., 41.

[10]Clinton retained numerous documents to counter second-guessing by superiors and politicians. After the war, he employed many of the saved papers to justify his actions and avoid criticism.

[11]Clinton, The American Rebellion, 84.

[12]Lord George Germain to Henry Clinton, March 8, 1778, in K. G. Davies, ed., Documents of the American Revolution, 1770-1783: Colonial Office Series(Shannon: Irish University Press, 1972), 15:57.

[13]Clinton, The American Rebellion, 122.

[14]For a discussion of General Howe’s plans and interactions with Lord George Germain see John Fortescue, The War of Independence: The British Army in North America, 1775 – 1783(London: Greenhill Books, 2001, reprint of 1911 edition), 52–65.

[15]For a description of the Rebel attack on Stony Point, see Henry P. Johnston, The Storming of Stony Point on the Hudson Midnight July 15, 1779 (New York: James T. White & Co., 1900).

[16]For a summary of the views of fellow officers and colleagues on Henry Clinton, see Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy, The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 224–25. An eminent military historian assessed, “Caution was Clinton’s watchword.” John W. Shy, A People Numerous and Armed: Reflections on the Military Struggle for American Independence (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990), 206. Another historian opined, “He overestimated his difficulties and then did not really try to overcome them.” Robert Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 598. A British historian averred that Clinton possessed “strategic timidity,” “played the game safely” and was “a very capable general in the field,” but crippled by self-distrust.” Piers Mackesy, The War for America: 1775-1783 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992), 144, 515, 213.

[17]Only George Washington served longer as a senior commander than Henry Clinton.

7 Comments

Wonderful article Gene! If Clinton’s plan had been followed in 1777 and Burgoyne’s force based itself out of NYC rather than Canada, it appears likely that Albany would have fallen. With British control of the Hudson River, New England would have been largely separated from the other colonies, depriving Washington’s Main Army of troops, cattle and other necessary supplies. As you said, the big question was “Could they have held it?”

We should indeed be glad that Lord Germain was in charge in London – and not Henry Clinton.

Is it possible that the failure to make use of General Clinton’s plan ~ and especially after Benedict Arnold arrived at his doorstep so conveniently! ~ somewhat explains Clinton’s failure to respond with appropriate speed and strength to Cornwallis’ need in Virginia? It always seemed to me somewhat astonishing that he could have failed to respond to that General’s obviously urgent requests for assistance! Cornwallis was certainly a man whose tactical view of any situation was trustworthy to say the least. That Clinton remained if not altogether unmoved in New York, then certainly lacking the urgency that the situation demanded was always something that I could not understand! It either speaks to his lack of understanding of the situation or, in the alternative, his disregard for Washington as a sufficiently able commander to defeat Cornwallis. Certainly Clinton’s reactions prior to Yorktown do not seem to be in keeping with his known abilities but he wouldn’t have been the first military leader who lost his “verve” when his plans were rejected.

Great article. I would like to bring up an observation about this time in the revolution; when the British occupied Philadelphia. Looking at a map of that time, I question why Howe did not send a small group up the Chesapeake Bay on the west side of the Susquehanna to attach Yorktown where Congress was in session. If Howe would act as to attack Washington, the “back door” in the bay would be open and it could be successfully used to capture Congress. At that time, the militia in Yorktown was in chaos and there were very few men guarding Congress and if successful Congress and our countries treasury could be obtained. This action could have ended the war.

Doug, thank you for your nice comments! Yes, the British strategy missteps lay at Lord Germain’s door. He promoted fundamental issues such as no supreme North American commander with three equal generals pursuing independent plans (Carleton, Howe, and Burgoyne). Additionally, he tried to lead from across the ocean despite untimely and imperfect information and without an “on the ground” commander. No wonder Howe and Clinton wanted to resign their commands!

Dennis, I appreciate your feedback and comment! I’m unsure of General Howe’s understanding of Susquehanna’s navigability, but you reinforce his lack of strategic creativity. Howe became fixated on defeating Washington in one giant battle and neglected political and economic strategies, which might have led to more success in ending the Rebellion. For more information on General Howe’s 1777 campaign planning, see my forthcoming April 2024 article in the Journal of Military History.

Thanks for your reply. I wasn’t clear about what I mean about the invasion. The west side

of the bay is a direct connection by land to Yorktown. The British could have landed above Baltimore and walked up the west side of the Susquehanna River directly to Yorktown, some 50 or so miles. Yorktown had no defense to the south of the town.

Howe landed on the east side of the Susquehanna when he attacked Philadelphia, he didn’t realize or know what was on the west side.