When the fighting between the British and American forces broke out on April 19, 1775, just one month prior to the start of the Second Continental Congress no one was sure just where things were going or how they were going to turn out, but one thing was acutely on everyone’s mind at the time. The thirteen American colonies were now faced with a war in which they were battling a nation with the largest navy in the world, an army that was flush with victory having won a stunning defeat of its archrival, France, and a nation that now had the largest empire the world had seen since the days of ancient Rome. Great Britain’s army was small, but highly trained and used to victories.

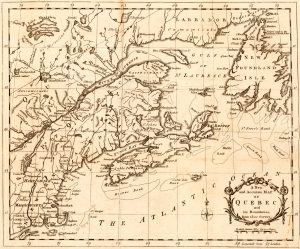

America was looking for friends. Could Canada be one of those friends? If the Canadians could overthrow their new British masters, it would go a long way in restricting British operations in America. At first there was talk in the Continental Congress of invading Canada that summer. That idea was quickly given up, but could the French Canadians be convinced to do it on their own? The Congress did send a letter written by John Dickinson in the First Continental Congress in 1774 to the French Canadians, but they did not respond.

In June 1775, John Hancock, president of the congress, wrote to General Philip Schuyler that due to “alterations of the sentiments of congress,” Schuyler was “to make an impression into Canada.”[1]

What had changed? Why did the congress think that an invasion of Canada should occur so early in the war? The congress had only just days before created and army and was still organizing its list of officers. There were, as yet, no regular soldiers. The actual fighting units were still made up of local colonial militia units. About a month earlier Silas Deane, a delegate from Connecticut, noted in his diary that “a Mr. Price of Montreal, was examined before the congress.”[2] James Price was an English merchant living in Quebec City, Canada and he was opposed to the Quebec Act that had been passed by the British parliament in 1774.

If the end of the French and Indian War changed the political status in the lower thirteen colonies, it drastically changed things in Canada. Quebec had been a French colony for two hundred years and the French speaking settlers suddenly found themselves no longer French, but citizens of the British Empire. A number of British settlers did settle in Quebec but the colony was still predominantly French speaking and Catholic. When the British government agreed to allow French Canadians to keep their civil laws and their religion by passing the Quebec Act, that upset a number of Protestant English immigrants in Canada. Also, the Royal Governor of Quebec, Sir Guy Carleton, had appointed a number of French Canadians to his inner council to help him govern the colony. This upset the English settlers even more.

Carleton became Governor of Quebec in 1766. His administration decided to rely on the traditional ruling class, the French siegneurs. The Quebec Act removed the old Test Act—French Canadians could now serve on the Governor’s Council and remain Catholic. The loyalty oath was made more acceptable to the French subjects. The Quebec Act stipulated that, while criminal laws would remain English, the civil laws would be French. Governor Carleton approved of the new act, but the new English settlers were shocked by it. Might they need a new set of “allies”?

In 1774 a group of British settlers in Canada sent a load of wheat to Massachusetts as a donation to the “destitute amongst innocent and necessiteous sufferers of the town of Boston.” Along with wheat they sent a note making contact with Samuel Adams. Then James Price arrived in Philadelphia to meet with the Continental Congress. After the meetings he returned to Canada with a letter to the Canadians from the Congress. This letter invited “their neighbors to join with the Americans in resolving to be free.”[3]

Around the first of June 1775, as the Second Continental Congress was meeting, they discussed the possibility of American forces invading Canada to destroy the British forces there and to prevent them from invading New York and occupying the Hudson Valley.

The issue was complicated. The last thing the congress wanted to do was open a can of worms and create a new set of problems, but many felt that the danger of leaving the back door open and allowing the British a secure place to launch an attack into the lower colonies was just to serious to ignore. John Adams wrote to James Warren in Massachusetts saying,

we have been puzzled to discover what we ought to do with the Canadians and Indians . . . whether we should march into Canada with an army sufficient to break the power of Governor Carleton . . . has been the great question. It seems to be the general conclusion that it is the best to go, if we can be assured that the Canadians will be pleased with it, and join.[4]

The letter to the Canadians that Mr. Price took to Quebec was different from the one that Dickinson wrote in 1774. It was addressed both to the French and English Canadians and was a direct invitation to join with the lower colonies in resistance to Britain. It read,

To the Oppressed Inhabitants of Canada:

Since the conclusion of the last war, we have been happy in considering you our fellow subjects . . . we perceived the fate of the Protestant and Catholic colonies to be strongly linked together, to join with us in resolving to be free, and in rejecting . . . the fetters of slavery.

By the introduction of your present form of government [the Quebec Act] or rather present form of tyranny, you and your wives and children are made slaves.

We, for our part, are determined to live free or not at all . . .

Permit us, again to repeat, we are your friends, not your enemies . . . The taking of the fort and military stores at Ticonderoga and Crown Point . . . was dictated by the great law of self-preservation. We hope it has given you no uneasiness . . . We yet entertain hopes of your uniting with us in the defence of our common liberty.[5]

In Canada the situation was very fluid. French nobles and the Catholic Church were very much behind Governor Carleton and his administration. French Canadians made up 90 percent of the population of Quebec.

The French Canadians were, for the most part, tenant farmers who farmed land owned by French seigneurs. Most farms were about 250 acres in size. Wheat was the primary crop. Each farmer also grew vegetables for their own use and had livestock. Part of the wheat crop went to the seigneur and part went to support the local priest. There was a seminary in Quebec City for training new priests in Canada. The priest was to officiate at various religious ceremonies and he was also responsible for the primary education of the children in the surrounding areas. Official documents were usually read to the public by the priest, as approximately 90 percent of the Canadian population was illiterate.

In addition to the seigneur and the priest, there was one more person who was to receive a portion of the farmer’s wheat, the captain of the local militia. He saw that the unit was properly drilled and equipped in the event of an emergency, and if the priest was unavailable, he was to read the newspaper and official proclamations to the public. These were the people who were the bulk of the population in Canada, and whole militia made up the bulk of the military units found in Quebec province.

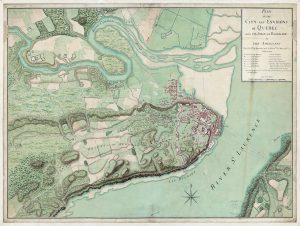

Governor Carleton did not many British regular soldiers to hold on to Canada. There were 250 regulars in Quebec City and 186 in Montreal, with the rest split up into small units and scattered all over the province. Carleton was in no position to invade anyone.

In addition, Carleton was having a really difficult time in getting intelligence on what was going on in Massachusetts and in the Continental Congress. The British, after the conquest of Canada, had set up a system for regular twice-weekly mail service from New York to Montreal, and when the Revolution began, Americans stopped that mail service. Also, all correspondence between known loyalists and Canada was intercepted. These facts plus an increasing number of incidents along the border gave Carleton enough of an alarm that on June 7, 1775 he declared martial law in Quebec province and called up the militia, a military force made up primarily of French Canadians.

British Canadians were by and large upset with Carleton over his call for martial law. They considered it an act of injustice. However, opposition to Carleton and the Quebec Act was one thing, joining forces with actual rebels in the lower colonies was quite another. Carleton was able to raise a regiment of non-French Canadians made up primarily of Scottish immigrants and Loyalists from New York.[6]

General Schuyler had just been given command of the army in the north when he began to get reports that Carleton was planning an attack into New York and that a group of Native Americans had joined the British regulars. The congress cited those reports when it issued its Declaration on Taking UP Arms:“We have received intelligence That General Carleton, The Governor of Canada, is instigating the people of that province and the Indians to call upon us.”[7] This turned out to be an error. Evan so, on June 26 the Continental Congress decided to revisit the idea of invading Canada. It authorized General Schuyler, the American commander in the northern area, based in Albany, New York with discretionary authority “to take possession of Saint Johns and Montreal and other parts of Canada and pursue any other measures in Canada . . . to promote the peace and security of that colony.”[8]

On August 1 the congress adjourned until September 13. The generals found themselves suddenly on their own and without congressional supervision.

After some time, a group of Canadians in a village called Chambly, decided they wanted to associate with the American rebels. They met and formed a militia unit, but not all had weapons. They sent a letter to Albany asking that the Continental Army come to Canada. The Canadians offered to supply the Americans with “cattle, horses, [and] carriages as needed.”[9]

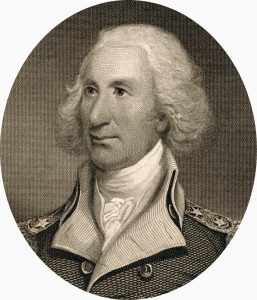

To further confuse the situation, Major General Schuyler had to leave Albany to meet with a group of Native Americans for a peace conference. This was a high priority in American policy at the time, to try and get the Native Americans to remain neutral during the war. Schuyler’s second in command, Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery, was left in charge. In the middle of all this, Montgomery received a letter from General Washington advising him that he was about to send Col. Benedict Arnold up the Kennebec River in Maine to attack Quebec in coordination with an attack from Albany. Washington wanted to make sure that such an attack was indeed going to take place. Washington concluded his letter with the words, “not a moment is to be lost.” Montgomery decided it was time to go.[10] Thus, the invasion into Canada was made by a brand-new brigadier general in a newly created army, while the government was in recess and the senior commander was away.

Nothing turned out like it was supposed to.

Montgomery first had to take the British fort at St. Johns, the gateway into Canada. This took several weeks as British regulars held on for as long as they could. Montgomery then moved on to Montreal and took the city. That city became the center point of the American presence in Canada. However, as the American forces got deeper into Canada their forces began to be spread thin. One officer wrote home that Montgomery never had more than two thousand men, and often, not that many. In capturing these two outposts Mongomery was able to capture a fair number of British winter uniforms, which he distributed to his men and had some left to give to Arnold’s men when they arrived. He also captured a number of cannon and some gunpowder.[11] He then moved on to Quebec City, the seat of government in Quebec province, to link up with Arnold. Arnold’s trip into Canada turned out to be a nightmare.

Arnold assembled his men at Fort Western, where the city of Augusta is now located. From there they would take boats up the Kennebec River that flowed out of northern Maine just below the boarder with Canada. He would then cross a series of lakes until they came to the Chaudiere River which flowed into the St. Lawrence River near the city of Quebec. Arnold had one thousand men with him and he was to link up with Montgomery at Quebec. He would be second in command to Montgomery, once the link was made. Both men were instructed to see to it that the men respected the property and religion of the Canadians.

Arnold and his men left for Canada in the early fall, on September 13, 1775. The lower part of the Kennebec River has small towns and farmland all around it. But once they left Fort Western, it was almost all wilderness and old-growth forests. Silas Deane of Connecticut, a man who knew New England winters, was worried that Arnold was leaving too late, as winters came early in Maine.[12]

On September 29 the column ran into shallow waters and had to spend several days portaging the boats and equipment over the shallow riverbed. By October 3 they had left all the settlements behind and on October 25 it started snowing. The day before, starvation had begun to settle in, and a number of men wanted to turn back. A war council was held and it was decided to send the “disaffected” back down the river with some of the supplies.[13] Those who returned amounted to 25 percent of the men. Arnold was now down to approximately 750 men. By October 26 they were still 150 miles from the nearest Canadian settlement. On October 27 the evening meal consisted of one hog jawbone with no meat, boiled in water with some flour. Breakfast the next morning consisted of what was left over from the meal the night before. The next day they managed to scrounge up one ounce of pork per man. The officers ate none, to leave more for the men. They calculated they had gone seven miles in three days.

On October 31, they reached the headwaters of the Chaudiere and now could go downstream to the St. Lawrence, but a few days later they wrecked one of the boats. All the weapons and gunpowder on that boat was lost. On November 1, they decided to leave the boats and heavy equipment behind to make faster time. Finally on November 3 Arnold and his exhausted, hungry and half frozen men reached a Canadian settlement and Arnold, who had been given some of the scarce hard currency that the Continental Congress had, was able to purchase supplies for his men. By now they appeared “more like ghosts than men.” On the first night in the village, each man had one pound of beef with corn meal, while the sick had mutton. Private Stocking, one of Arnold’s men, reported that, “we sat down, ate our meal, blessed our stars, and thought it luxury.”[14]

When the men of the Continental Congress got word of Arnold’s trip, one North Carolina delegate wrote back home saying, “Arnold’s expedition has been marked with such scenes of misery that it requires a stretch of faith to believe human nature was equal to them, subsisting on dead dogs, devouring their shoes, and eating their cartridge belts, are but a part of the catalogue of the attended expedition.”[15]

After reaching the area around Quebec, Arnold and his men were met by a number of Canadians who were sympathetic to the American cause and helped replenish his equipment and make contact with General Montgomery.[16]

By the time Arnold had linked up with Montgomery it was late November. It took some time to reorganize and re-equip Arnold’s column with the equipment that Montgomery had captured. They decided to try and take Quebec in the early morning of December 31, 1775. Just before the attack bagan it started snowing and kept snowing throughout the night. But it was decided to continue with the attack. The signal to begin was a rocket fired by Montgomery.[17]

Arnold and Montgomery each attacked from different positions. Montgomery personally led the attack on his front. He helped clear the way through two obstructions put up by the city’s defenders. As he and his men started the attack on the main objective a British cannon fired grape shot into the American column. Montgomery, his aid-de-camp and twelve men were killed instantly. Aaron Burr, who had made the trip up the Kennebec with Arnold and had been sent to Montgomery to act as his liaison, tried to pick up Montogomery’s and remove it to the American lines. Burr stood only five feet six inches, and found that he had difficulty carrying Montgomery’s much taller body in the snow while under fire and retreating; he finally had to give up the effort and make it back to American lines himself. Montgomery’s second in command, rather than pushing on the attack, called for a general retreat. But Burr’s attempt to save Montgomery’s body had not gone unnoticed and was reported back to the congress in Philadelphia. One member noted, “Mr. Burr, son of the late President of Princeton college, behaved well, as they say, in the affair at Quebec.”[18]

Arnold’s troops had missed the rocket signal in the snow storm and were late in launching their attack. Arnold, too, was leading the attack from the front, was seriously wounded in the leg, and had to be carried back to the rear. His men continued the attack and a number of them broke through at one point, but were eventually surrounded and cut off. They tried pushing through but were met by intense fire from inside the city each time they tried. There was no way to go back and they could not go forward. Finally at nine in the morning the officers in command of the surrounded detachment ordered a surrender. Some 372 men were captured in addition to the wounded. One wounded soldier later wrote, “It was apparent to all of us that we must surrender. It was done.”[19]

After both attacks were broken off, Arnold, as the senior officer present, took command of the shattered American army. He dug in around the city, keeping the British forces bottled up inside. He then waited for reinforcements from the colonies to the south. Burr stayed with Arnold until May 1776 when he returned to the army in New York and was added to Washington’s staff.[20]

After the attack was over, Carleton was impressed. Many of the units that had defended Quebec were French Canadian militia. They had fought well and had basically saved the day. He ordered the body of General Montgomery be treated with distinction and the American prisoners to be well treated.[21]

Americans back home were stunned by the defeat. On January 8, 1776 one congressman noted that, based on reports from generals Schuyler and Montgomery, if the United Colonies wanted to hold Canada, they were going to need ten thousand more men. The congress had assumed that the Canadian operation would be self-sustaining once the initial objective of taking Canada was completed. It was assumed that Canadians would wantto be added to the United Colonies and would send delegates to the congress and raise their own militia. In addition, the congress was getting constant requests for hard currency to be sent to Canada. It seems the Canadians were very happy to continue to supply the American army as long as they were paid in real money, not Continental paper dollars. The generals said that without more money and more men, “all will be lost.”[22]

With dire news coming almost daily out of Canada, the Continental Congress decided to send a commission to put their eyes on the situation and see what could be done. On February 15, three men were chosen and given full powers to act in the name of Congress. Samuel Chase of Maryland and Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania were members of congress; Charles Carroll of Carrolton, from Maryland, was not, but he was one of the richest men in America and a Catholic. In addition, he spoke French fluently. Even though not a member of congress, he was given full and equal status with Chase and Franklin. As he had been extremely keen on the Canadian expedition, Chase became the “defacto leader” of the commission.[23]

The commission was given full authority to settle all disputes between the Canadians and the Continental troops. There had been increasing reports of contention between the two and of depredations against the Canadians. The instructions to the commission stated,

in reforming any abuses you may observe in Canada . . . all officers and soldiers are required to yield obedience to the decisions any two of you may make; you are empowered to suspend any military officer from the exercise of his commission . . . you are also empowered to sit and vote as a member of the councils of war.[24]

As the winter went on, the news from Canada grew increasingly worse. One American brigadier general reported that the American army consisted of “a few more than two thousand men, of which twelve hundred were unfit for duty with the small pox, and of the eight hundred men fit for duty, six hundred were past their enlistment dates and were waiting for their replacements to that they could go home”.[25] Meanwhile, John Hancock, president of the congress, received letters from a number of other senior officers in Canada. They told of low morale among the men, shortages of money and supplies, and a sudden upsurge of Canadian hostilities and Native American attacks on Americans.

In May the commissioners to Canada began to make their reports to the congress, and they were not pretty.

It is impossible to give you a just idea of the lowness of the Continental credit here from the want of money . . . not the most trifling service can be procured without assurance of instant payment in gold or silver. The general apprehension that we shall be driven out as soon as the king’s troops arrive, [and] with the frequent breaks of promises the inhabitants experience in determining to trust our people no further . . . The utmost dispatch should be used in forwarding a large sum of money hither (we believe £20,000 will be necessary)[26] . . . The troops now before Quebec have not ten days provision . . . We are told that eight thousand [men] will make a sufficient army [to hold Canada] as yet there are but three thousand including those now passing the lakes [on their way here].[27]

In May the army was retreating. It hoped to hold on to Montreal and some forts along the frontier, but even that seemed difficult. The commissioners wrote to General Schuyler in Albany that,

Our army is now on its way to the mouth of the Sorel where they hope they [will] prepare to make a stand . . . It is very probable that we shall be under the necessity of abandoning Canada . . . a further reinforcement will only increase our distress; an immediate supply of provisions from the lakes is absolutely necessary for the preservations of the troops already the provence . . . no provisions can be drawn from Canada, the subsistence therefor of our army will entirely depend on the supplies we receive, and immediately from Ticonderoga.[28]

On May 5 the Americans learned that British reinforcements had arrived. Five warships and a convoy of transports had just landed ten regiments of British regulars, some 5,000 troops, joining 850 Canadian Loyalist militia. The Americans decided to withdraw to positions around Montreal and establish a defensive line. Unfortunately, the withdrawal was so rapid that outlying posts of American units were left behind, most of which wound up as prisoners of war. In mid-May the commissioners were still begging for money from the congress, “a sum of money to discharge the debts already contracted, which General Arnold informs us amounts to £14,000, besides the accounts laid before congress a further sum of money, not less than £6,000.”[29]

The problem was made worse as the congress was sending additional battalions to Canada, but totally without supplies. Recently ten battalions had arrived with no supplies and the commissioners wrote that “we now have four thousand troops in Canada and not a mouthful of food . . . necessity has forced us to take possessions” by force. They reported that at one outpost were 900 men defending the entrance to the state of New York, but that “they were without canons except for a few pieces without carriages . . . My God, an army of ten thousand men without provisions or powder”[30]

The commissioners then told of one post that was about to be attacked by a combined force of British regulars and Native Americans loyal to Britain when the officer commanding the American unit fled, leaving some three hundred of his men in no condition to face the enemy, having had no food to eat for the last four days, except bread.[31]

Finally on May 17, the commissioners wrote to Hancock saying that “we think our stay here is no longer of service to the republic . . . and we wait with much impatience the further orders of congress.”[32] Franklin had already left. They were saying that they were done, as was the American army in Canada. On May 27 the commissioners reported that “the army is in a distressed condition and is in want of the most necessary articles, meat, bread, tents, shoes, stocking, shirts . . . such is our extreme want of flour that we were yesterday obliged to seize by force, fifteen barrels to supply the garrison at Montreal with bread.”[33]

On June 13, Arnold advised that it was time for the American army to quit Canada.[34] British troops were arriving in increasing numbers and the American army was under fed, under equipped, and had large numbers suffering from smallpox. On June 16, Montreal fell to the British, after having been the center of American activity in Canada for the pasts six months. By this time the retreat was becoming a route and on July 1, three days before he Declaration of Independence, Arnold and the American army retreated into New York.[35]

With the evacuation of Canada, the investigation and finger pointing began. Elbridge Gerry, a delegate from Massachusetts, wrote to the governor of his colony saying,

The congress is determined to search the wound and probe it to the bottom and be assured your delegates will see it laid open . . . why have not the supplies that were necessary been sent to Canada and the men well paid? What officers have failed or been negligent in their duty[36]

On June 24 the congress formed a committee to investigate what went wrong in Canada,[37] and on July 30, almost a month after declaring independence, the committee made its report. In short, they found that,

Short enlistments of the Continental troops in Canada have been one great cause . . . which prudence might have been postponed . . . miscarriages in rendering the supplies necessary or difficult to procure [and] the precarious establishment of proper magazines absolutely impractical, and the pay of the troops of little use to them. That still a greater and more fatal misfortune had been the prevalence of small pox in the army. A great portion thereby were unfit for duty.[38]

As the American army retreated, Gen. Sir Guy Carleton had to rebuild and reorganize his shattered colony. For eight months there had been heavy fighting and sieges in and around various cities and village in Quebec. He began by heaping praise on the French Canadians who had remained loyal to Britain throughout the fighting. Indeed, it could be argued that it was they who had saved the day. He also quickly paroled those Canadians who had served with the American army. They were sent home on promises of good behavior. There were no floggings, no arrests, no property seized and no burnings. The British and newly-arrived Hessian troops were ordered to pay for all supplies and services with cash. He also saw to it that all captured Americans that were wounded and ill were hospitalized and treated with kindness. As soon as they were well enough, he sent them back to America with all the other prisoners upon their parole that they would not take arms against Britain again.[39] One might well compare Carleton’s treatment of dissidents with that of the American Sons of Liberty record of arrests, beatings, destruction of property and property seizures, as well as the tarring and feathering of Loyalists.

The following year the fear of a British invasion into the lower colonies was realized when British General John Burgoyne led a combined force of British regulars and Hessians out of Canada and into New York to be met by a stalwart American army at Saratoga.

[1]John Hancock to General Schuyler, June 28, 1775, Paul H. Smith, ed., Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774–1789 (Washington: Library of Congress, 1977), 1:554 (Letters).

[2]Silas Deane’s Diary, May 27, 1775, Letters, 1:412.

[3]Mark R. Anderson, The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony: America’s War of Liberation in Canada, 1774-1776 (Hanover, NH and London: University Press of New England, 2013), 66-67.

[4]John Adams to James Warren, June 7, 1775, Letters, 1:452-453.

[5]Journals of the Continental Congress (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904-1937), May 29, 1775, 2:68-70 (Journals).

[6]Anderson, The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony, 83-84.

[7]Journals, July 6, 1775, 2:152-153.

[8]Journals, June 27, 1775. 2:110.

[9]Anderson, The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony, 97, 99-100.

[11]Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris, eds., The Spirit of Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by the Participants (New York: Da Capo Press, 1958), 188-189.

[12]Anderson, The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony, 145-146.

[13]Commager and Morris, The Spirit of Seventy-Six, 192-201.

[14]Anderson, The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony, 147, 201.

[15]North Carolina Delegates to Samuel Johnston, January 2, 1776, Letters, 2:18-19.

[16]Anderson, The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony, 150-151.

[18]Richard Smith’s Diary, January 19, 1776, Letters, 3:113.

[19]Commager and Morris, The Spirit of Seventy-Six, 206-209.

[20]Milton Lomask, Aaron Burr: The Years from Princeton to Vice-President, 1756-1805 (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1978), 40.

[21]Anderson, The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony, 198-199.

[22]Richard Smith’s Diary, January 6, 1776, Letters, 3:50.

[23]Joel Richard Paul, Unlikely Allies (New York: Riverhead Books, 2007)290-293.

[24]Journals, March 5, 1776, 5:215-218.

[25]Anderson, The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony, 310.

[26]An impossible sum of money for the congress to raise at that time.

[27]Commissioners to Canada to John Hancock, May 1, 1776, Letters, 3:611.

[28]Benjamin Franklin to Philip Schuyler, May 12, 1776, Letters, 3:666.

[29]Commissioners to Canada to John Hancock, May 8, 1776, Letters, 3:639-640.

[30]Commissioners to Canada to John Hancock, May 17, 1776, Letters, 4:22.

[31]Samuel Chase to Richard Henry Lee, May 17, 1776, Letters, 4:23-24.

[32]Commissioners to Canada to John Hancock, May 17, 1776, Letters, 4:23-24.

[33]Commissioners to Canada to John Hancock, May 17, 1776, Letters, 4:81-84.

[34]Anderson, The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony, 316.

[36]Elbridge Gerry to James Warren, June 15, 1776, Letters, 4:220-222.

[38]Report of the Commissioners into the Canadian Expedition, July 30 & 31, 1776, Journals, 5:617.

Recent Articles

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

Recent Comments

"Contributor Question: Stolen or..."

Elias Boudinot Manuscript: Good news! The John Carter Brown Library at Brown...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

The new article by Victor DiSanto, "The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched...

"Quotes About or By..."

This well researched article of selected quotes underscores the importance of Indian...