John Adams said of his Whig contemporaries that they had views as “various as the Colors of their Cloths.”[1] Such was the paradigm in the civil yet often contentious political relationship of Abraham Clark and William Livingston. Both men were, as the saying goes, cursed with being born in interesting times. They were the top political leaders of New Jersey during the tumultuous years of the American Revolution. Hailing from the “second tier” of Founding Fathers, they nonetheless made significant contributions to the establishment of the United States. Livingston believed in strong central government, and Clark believed it tyrannical. However, the shared struggle of asserting America’s rights, defending New Jersey, and winning the war forced them to work together in a common cause. Their differences in the beginning were petty but grew more substantive as time progressed.

Clark was a perennial legislator who served in the Continental Congress and New Jersey state legislature. His ideological opponent Livingston was a member of the First and Second Continental Congresses and the longest serving governor of the Revolution. Clark signed the Declaration of Independence, and Livingston, the Constitution of 1787. Their political rivalry, which started poorly, began as the British were delivering their massive military counterstroke in the vicinity of New York City during the summer of 1776.

In the last days of June 1776, Abraham Clark, surveyor, farmer, and self-styled advocate for the people, and nicknamed the “poor man’s counselor,” packed necessities for an eighty-mile journey from Elizabethtown, New Jersey to Philadelphia to take his seat in the Third Continental Congress. Middle-aged, frail, and with seriousness chiseled on his face, Clark knew Congress’s agenda for the first days of July was to be of a weight and significance not seen in his many years in government. His small house west of Elizabethtown’s center housed his large family. From there, he wrote to his neighbor Elias Dayton, colonel in the Continental Army, “Our Congress have determined upon a new form of government, and are drawing it up. The Continental Congress are to determine next Monday upon Independency. I am going among them tomorrow.”[2] Clark and three other members of the New Jersey delegation were instructed by the legislature to support declaring Independence if necessary to preserve “the just Rights and Liberties of America.”[3]

A French diplomat described Abraham Clark as a “Man of the people . . . despised by gentlemen and returning the sentiment to them with interest.” Clark was an only child, from an old Elizabethtown family of civic leaders who were devout Presbyterians. Modestly educated, he was a surveyor during a boom time for the profession. Despite being sole inheritor of substantial landholdings from his father, Clark nonetheless considered himself a yeoman farmer. He blamed the King for the crisis gripping the colonies, and his primary focus during his years in politics was twofold: advocate for common citizens and fight centralized power in all government institutions.

Clark’s political career started with a clerkship in the colonial general assembly. His transformation into a Revolutionary started with his being chosen by Elizabethtown’s freeholders in December 1774 to direct the town’s boycott of British goods. Clark represented Essex County in the New Jersey legislature in the summer of 1776.[4] The legislature was controlled by members swept into power on a wave of populism fired by an expanded franchise. Its members were inexperienced in government but motivated to public service by the emerging crisis.[5] Clark was serving with them when the call came to go to Philadelphia. He wrote Colonel Dayton on July 4, “Our Congress is an August Assembly, and can they support the Declaration now on the Anvil, they will be the greatest Assembly on Earth.” Clark’s signature is preserved for posterity on the Declaration at the bottom of the New Jersey delegation.[6]

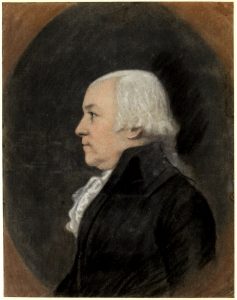

Living north of Elizabethtown in a palatial home built in 1772 for his retirement, New York ex-pat William Livingston was incensed by Abraham Clark. Tall, long faced, and hawkish nosed, the Dutch- and Scottish-mixed Livingston was fifty-three years old and hailed from a powerful upstate New York family that ran a mercantile empire. The former lawyer was supposed to be enjoying an early retirement immersed in books, but was instead serving New Jersey as representative in the Continental Congress. Livingston believed Clark conspired with allies in the legislature to replace him in Congress. Clark told his close friend Dayton that Livingston, “seems much Chagrined at his being left out of Congress, and there is not wanting some who Endeavor to persuade him that it was through my means to Supplant him, which was far from true.”[7]

As a consolation prize to the aggrieved Livingston, the New Jersey legislature commissioned him a brigadier general in the militia. This did not heal his wounded pride right away, and he endured the humiliation of receiving a letter dated July 5 from Clark, informing him of the Declaration of Independence’s passage. This was by no means malicious on Clark’s part; Congress recommended that commanders in the field receive the Declaration. Clark told his rival, “I have no doubt you will Publish in your Brigade.”

The measure Livingston feared was now a reality.[8] He had fallen out of favor with the legislature due to his hesitancy to back independence. He whole-heartedly supported economic boycotts in addition to voting yes on The Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms resolution passed by the Second Continental Congress. His trepidation, and those of like mind, stemmed from a fear that independence would unleash mob rule and violence.

In public life, Livingston was introverted and seldom sought public attention. This trait outwardly concealed his effectiveness and killer instinct toward political opponents. His letters to friends and family were exceptionally heartwarming, but his political correspondence was serious and confrontational. His favorite end-around weapon was the satirical polemic, which he started writing as a hobby during his law apprenticeships.

Livingston, a Yale graduate, eschewed religion, and embraced the ideas of The Enlightenment. Consequently, he undertook a lifelong crusade against the establishment of religion and the Anglican Church in particular. In 1752, Livingston along with two young lawyers practicing in New York City, known as “The Triumvirate,” published a weekly newspaper called The Independent Reflector. In short, the Reflector’s fifty-two issues of satirical propaganda attacked the establishment of a particular religion in the colonies. The paper used ample word space on the Anglican Church and the DeLancey political faction which supported it. Livingston avidly worked to prevent nascent King’s College (Columbia University) from falling under the influence of the church.

The countryside of northern New Jersey was introduced to Livingston through his wife Suzannah French. In theory, Elizabethtown was far enough away for a peaceful retirement, and the ferry to New York City would keep him connected to Manhattan’s bustle. This fell by the wayside as his natural proclivities won out and the crisis with Britain expanded. Unlike Clark, Livingston was a conservative who blamed Parliament for the crisis rather than the King. He formed political associations with like-minded men on Clark’s turf. One such alliance was with future Congress president and Elizabethtown resident Elias Boudinot.

The military command which superseded Livingston’s coveted seat in Congress was nevertheless executed by him with vigor and competence. Clark was in Philadelphia and feared that his hometown would be “laid to ashes,” and a rival, Livingston, headquartered there was charged with protecting it. Livingston oversaw the construction of redoubts and fortifications along the coast. He positioned troops at strategic points, and adeptly managed issues of supply and manpower; in the process, he established a rapport with Gen. George Washington. Boudinot was Livingston’s aide-de-camp, and he had a solid Continental Army connection in the person of Gen. William “Lord Stirling” Alexander, his brother-in-law and old friend from New York City.

As the calendar turned from August to September 1776, the man who showed little promise in his father’s eyes and had lost his first law apprenticeship for cause was chosen governor of New Jersey under its first constitution. The legislature chose Livingston on the second ballot of voting, for reasons that are uncertain. If Livingston had a modern resume, his introduction would read “received promotions of increased responsibility.” He was chief executive alongside a legislature comprising a Legislative Council, and a lower house, the Assembly. The New Jersey constitution made the governor commander-in-chief of the state’s armed forces. Livingston, as such, faced enormous challenges as a wartime governor including stopping “London Traders” from supplying the enemy. The main concentration of British forces in America was nearby at New York City; and Staten Island, with its disaffected garrison of Royal Provincials and Refugees, was perilously close to Elizabethtown. Elizabethtown itself was the gateway to New Jersey, and thus, his home, and much of the state, was in the direct path between the British army and the rebel capital at Philadelphia.[9]

Clark and Livingston had a professional and prickly relationship. Few of Clark’s letters survive, but Livingston’s ample record sheds light on some of their squabbles. On July 26, 1776, a month after Livingston was relieved from Congress, and no doubt still nursing his wounded pride, he sarcastically offered up Clark as a candidate to command New Jersey soldiers in the Flying Camp. Livingston wrote to New Jersey legislator Samuel Tucker:

As every private Gentleman has a right humbly to submit his opinion to Superiors for the public good, & as the reason why I was so strongly pressed to take command of Brigadier Heards Brigade now ceases by my being superseded as a Member of Congress, I would with all Deference recommend Jonathan Sergeant or Abraham Clark Esqrs. to that Post—as those Gentleman have always shewn the warmest Patriotism in the Cabinet, I doubt not they will with equal Alacrity venture their lives in the field.[10]

In November 1779 Clark was serving in Congress when he learned that an officer named Silvanus Seely was a suspected London Trader. Seely, a colonel in a New Jersey regiment, was supposedly running supplies to the British from Elizabethtown. Clark reported the matter to Governor Livingston. Livingston wrote to Seeley, “I hope Mr. Clark’s Information as far as it respects itself not well founded.” Seely challenged Clark’s claim and insisted on a court of inquiry, and Livingston promised to submit his counterclaim to Clark. Clark continued pursuing Seely and was unhappy that Livingston did not press matters further, accusing him of “sporting with the Laws.” Livingston replied, “If therefore it is of any Consequence, or concerns the Dignity of Government, that I should know the particulars from which you have drawn this charge against me, you will occasion to explain the Matter more fully.” It was but one of a number of scrappy exchanges between the two.[11]

The matter of Cornelius Hatfield, Jr. illustrates the commitment Clark had regarding the priority civil authority had over military authority, while at the same time highlighting the family ties of small colonial communities. The Hatfield family of Elizabethtown, like the Clarks, were highly respected and went back to the town’s founding. Abraham Clark’s wife Sarah was a Hatfield and cousin to a young man caught loading a ship with supplies for the British. Cornelius Hatfield, Jr. was arrested and incarcerated in Elizabethtown’s provost to await his fate while under the care of General Maxwell.

The Essex County Supreme Court issued a writ of habeas corpus for Hatfield’s release. General Maxwell, who claimed he was waiting for more clarity on how to proceed, verbally and physically abused a handful of unlucky deliverers of the writ. On December 21, 1778, Clark wrote Continental Congress President and William Livingston’s son-in-law John Jay, pointing to Hatfield’s guilt but that the latter “is an inhabitant of this state and entitled to the privileges of the same, where the civil authority is fully competent for the trial and punishment of offenders, I believe fully competent for the apprehending General Maxwell for the contempt shown to it in the present case.”[12]

Clark followed up his letter with one to Livingston pressing his case for Hatfield’s release and accusing him of wanting Hatfield executed. Livingston responded that Clark’s case was “founded on mistakes of both fact & of law.” During wartime, “the military had a right to take up & secure persons guilty of practices that endangered the army till they could be delivered up to the civil power.” Livingston was caught between a community he recently became a part of and governed with limitations, and Congressionally empowered General Washington who implored governors to squash London Trading. The governor paid a fruitless visit to Maxwell’s headquarters to get his side of things, and wrote to Clark, “I do not think to myself vested with any judicial authority” and that the “officer in charge to whom [the writ] is directed is punishable by Law, but not responsible to the Governor.”

Livingston punted the issue to Washington. Clark never refrained from challenging the military, Washington included, and a refusal from the general to release Hatfield surely would have triggered more protests. Washington assented to Hatfield’s release, which was irrelevant because he had escaped to Staten Island. Hatfield guided a nighttime raiding party from Long Island to Elizabethtown just days after his flight. Burning buildings on their way, they marched to Liberty Hall with an intent to capture the governor. Livingston was away, but was shocked at the audacity of the venture and wrote with sardonic humor, “General Clinton thought proper to send an Express for me to Elizabeth Town.”[13]

After the war, New Jersey and its political class struggled to meet its obligations in the Federalist program to pay the national debt. The United States was in an economic depression and New Jersey’s economy was especially hard hit. Abraham Clark was serving in the New Jersey General Assembly in the Fall of 1785 when he lamented the state’s shortage of hard currency due the Federal government. “To Attempt to raise by Taxation the Sum required in Specie will be vain and fruitless; in this State it cannot be done.” New Jersey, unlike its wealthier neighbors New York and Pennsylvania, did not possess a bustling large port for imposing import duties, and also lacked large reserves of western lands to sell.

Clark’s concerns stemmed from a game-changing law passed by Congress on September 27, 1785. New Jersey was assigned a quota of $166,716 toward the national debt with one third required in hard currency. The dollar figure was based on a pre-war population estimate which Clark felt outdated and inaccurate. The specter of centralized government abuse haunted Clark’s mind:

This is a burden too unequal and grievous for this State to Submit to. We are ready to bear our part in the defense, and also of the expense necessary in Support of the Union, provided the same can be done in a just equal and practicable way, but Oppression will make even a Wiseman mad.

The Articles of Confederation governing the United States prevented Congress from directly taxing the states. The September 1785 act contained a clever mechanism to ensure that each state legislature approved the requisition, and that United States’ domestic debt was effectively cancelled. To settle this, Congress agreed to reduce a state’s liability to the federal treasury by the amount of domestic debt the federal government owed a state’s citizens.

Under the new law, New Jerseyites could take a Continental note to a federal loan officer and receive an interest-bearing certificate that could be used to pay taxes imposed on them by the state to pay for the requisition. This circular arrangement shifted tax collection to the state legislatures. The legislatures redeemed a citizen’s interest-bearing certificate to Congress—not for cash, but for cancellation of a portion of its requisition liability to the federal treasury. The plan circumvented the Articles of Confederation, driving Clark to call it a “scheme,” and he determined a course of action to resist it.[14] On November 8 Clark, then serving as an Essex County Assemblyman, introduced a resolution delaying a vote on the federal requisition until the legislature’s next session.[15] Peacetime Gov. William Livingston was being pressured by the federal government to get the legislature in line.[16]

The fuss over the requisition ran concurrently with Clark’s push to assist New Jersey’s yeomanry by issuing paper money. Shortage of currency stimulated waves of petitions to the legislature from farmers across several counties. Fortunately for the petitioners, the incoming legislative class of New Jersey Assemblyman elected in October 1785 held several paper emission champions.[17]

The recess of the legislature in the fall provided Clark time to prosecute his information campaign to dissuade the electorate against the requisition. Clark also took up the cause of greasing New Jersey’s economic engine by placing non-specie paper currency into circulation. Livingston was a member of the creditor class exposed to the danger of inflationary paper currency and, like many, was turned off to the idea from experience with the Continental dollar in the Revolution. Livingston could not resist the temptation to unleash his polemic writing skills on Clark.

Clark chose Elizabethtown printer Shepard Kollock and his The Political Intelligencer and New Jersey Advertiser as his delivery device. He chose “A Fellow Citizen,” and “Willing to Learn,” as his pseudonyms. Isaac Collins’ Trenton-based New Jersey-Gazette published Livingston’s “Primitive Whig” series to answer Clark. Other authors of unknown identity, mostly on Livingston’s side, published pieces jabbing at the pro-paper, anti-requisition supporters.

On December 14, 1785, Abraham Clark, as “Willing to Learn,” launched the opening salvo in The Political Intelligencer. The 1,200-word piece was an emotional appeal in support of the paper money. Clark promulgated that the soul of the American Republic was the guarantee of equality for common people, and that:

By misfortune or otherwise, [they] owe money which it is not now in their power to pay, many of whom are obliged to submit to prosecutions, and to have their estates sold far below the value to the breaking of families and increase of poverty, and to the promoting that inequality of property which is dangerous in a republican government . . . without a doubt, that is in the power of our legislature at their next sitting to remedy all those grievances and put a new aspect on our affairs.

Willing to Learn asked for the immediate printing of 200,000 pounds to be placed in New Jersey’s loan office and made immediately available.[18]

One week later Clark published his second piece under Willing to Learn. Clark’s essay confronted the elephant in the room—the nightmarish experience of paper money during the Revolution. Clark offered that the legislature could tame inflation by interest rate manipulation. He issued a challenge in a way that inspired Livingston and others to action by way of attacking the gentleman-creditor class of New Jersey:

Behold the farmer with his head uncovered saying, Sir, I am in necessity for the three shillings in hard cash to pay my tax; I have paper money, but that will not do, can you help me to that sum? I will suppose two different answers to be given in such cases, and your imaginations may paint as many more as you think may be given.

Clark’s hypothetical gentleman responded to the farmer:

D—n you and your paper rags, you have got it made and you may wipe your a-s with it, for you see the assembly won’t take it for their wages, and I’ll see you all d—d together before you shall have any had money for me . . . Yes I have a little hard money, but it is hard for you get it; but I believe I must let you have it. I saw some cleaver shoats near your house the other day, I supposed were yours, if you will fetch me a likely barrow, I will give you three shillings for it.[19]

On January 9, 1786, the first essay in Livingston’s “Primitive Whig” series appeared in the New Jersey-Gazette. The governor tackled the requisition, questioning the patriotism of those “Americans who promised to stand by Congress and General Washington with their lives and fortunes in opposing the mediated tyranny of Britain, now grumbling about paying the taxes.” And on the paper money issue and attack of creditors like himself, the Primitive Whig commented:

To see a lazy, lounging, lubberly fellow sitting nights and days in a tippling house, working perhaps but two days in the week, and receiving for that work double the wages he earns, and spending the rest of his time in squandering those his non-earnings in riot and debauch, and then complaining, when the collector calls for his tax, of the hardness of the times, and the want of a circulating medium-Ingrate!

Livingston characterized non-requisition supporters as London Traders and conflated the position with disloyalty. For Clark’s hypothetical destitute farmer, the Primitive Whig remarked, “But who is that yonder honest looking farmer, who shakes his head at the name of taxes, and protests that he cannot pay them! Why, he is a man whose three daughters are under the discipline of a French dancing-master.”[20]

Clark answered with two pieces in the January 11, 1786 Political Intelligencer, one under the pseudonym, “A Fellow Citizen.” A Fellow Citizen’s tone was sober and simple, short in length, and without any satire attacked the all-at-once approach of the federal requisition:

The general policy of most nations, either from the impracticability of inexpediency of the measure, doth not attempt to said the supplies necessary for the annual expense of government, by the ordinary mode of taxation only; it is done principally by the imposts and excises, which collects a revenue gradually, and almost imperceptibility, and at the same time voluntary from the consumers in equal proportion to their circumstance and abilities.[21]

The impost mentioned by Clark was a committee brainchild of Congress in the middle years of the war to pay the confederation’s debts. In 1781, a five percent tax was proposed on all imports into the United States. This nationalized mechanism for raising revenue was supported by Clark despite its inherent violation of his principles. The positive for New Jersey was that the federal treasury would be topped off by states with larger ports while poorer states paid their respective smaller portion. This failed along with a similar impost measure in 1783.[22]

The “Primitive Whig” reappeared in the January 16 New Jersey-Gazette. Livingston attacked paper money as “hocus pocus” and tied the effort to enact it as a reelection gimmick:

The mischiefs to be apprehended from so fatal a measure are almost innumerable; and as all of them are not likely to occur to one man . . . Who are the men that are in favor of paper money? They are, generally, debtors; and debtors, by their own confession, utterly irretrievable without this iniquitous device . . . It is therefore their hopes of the depreciation of this money, that is the whole burden of the song. And thus the business is eventually to terminate in the shifting the creditor instead of paying the debt, or the finally sham payment of it in depreciated currency, to their great consolation indeed as to the saving their bodies from imprisonment, but to the evident exposition of their souls to eternal perdition for such bare-faced knavery.

Livingston confronted the interests of creditors including himself, asking:

who are against emission of paper money, being creditors and men of property, are also self-interested in their opposition to it. Granted. But great is the difference between the self-interest and honesty of these and that of the debtors in question. The interest of the creditor coincides with that of the community. Not so the interest of the debtor. The former desires no more than his own. The latter wants to pocket the property of another.[23]

Livingston’s last Primitive Whig essay appeared in the New Jersey-Gazette on February 13. On February 8, Shepard Kollock had published Abraham Clark’s pamphlet The True Policy of New-Jersey, Defined. Published under Clark’s A Fellow Citizen pseudonym, it was a summary of his newspaper arguments.[24] In The True Policy, Clark summoned his ideology, stating that artisans, farmers, and mechanics were the backbone of New Jersey, and that republicanism would triumph with the printing of currency. Clark believed in grass roots campaigns, and A Fellow Citizen asked the people of New Jersey to pressure their representatives with “humble petitioning only, and no doubt you may be heard.”[25]

Clark returned to the General Assembly after its winter recess. He introduced the kill shot to Congress’s tax requisition on the floor of the legislature in Trenton on February 20. The information campaign, along with any unseen pressures, yielded a harvest of yeas that rebuffed the federal government’s debt program.[26] On March 7, a panicked Congress responded by dispatching envoys to Trenton to “represent to them, in the strongest terms, the fatal Consequences that must inevitably result to the said State, as well as to the rest of the Union, from their refusal to comply with the requisition of Congress.”[27] In addition, Clark and the populists were victorious on paper currency when, on March 9, the legislature approved the printing of money and bills of credits.[28]

The failures of the federal imposts of 1781 and 1783, and the requisition of 1785, exposed the fiscal weakness of the United States under the Articles of Confederation. Governor Livingston supported all three, while Clark supported only the imposts. Clark was never comfortable with the end product of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, yet in some way he helped create it by defeating the requisition. Clark and Livingston were chosen to represent New Jersey at Philadelphia:

To His Excellency William Livingston, and the Honorable Abraham Clark, Esquires, Greeting. The council and assembly reposing especial trust and confidence in your integrity, prudence and ability, have at a joint meeting, appointed you . . . to meet such commissioners in as have been appointed by other states in the union at Philadelphia . . . for the purpose of taking into consideration the state of the union, as to trade and other important objects, and of devising such other provisions as shall appear to be necessary, to render the constitution of the federal government adequate to the exigencies thereof.[29]

Clark had been re-elected to Congress (then meeting in New York), and therefore declined his invitation citing a conflict of interest. Livingston was enjoying life as a peacetime governor, spending more time with his family and books in Elizabethtown when the call to Philadelphia came. In Philadelphia, Livingston was his usual introverted self, and James Madison did not mention him making any speeches in the debates. Livingston did, however, serve as chairperson for two committees that waded through state debts, the militia, and the importation of slaves. Livingston’s signature can be found on the Constitution of the United States.[30]

Abraham Clark wrote to a fellow New Jersey assemblyman expressing his displeasure in the Constitution: “I never liked the System in all its parts. I considered it from the first, more a Consolidated government than a federal, a government too expensive, and unnecessarily Oppressive in its Operation; creating a judiciary undefined and unbounded.” Despite his misgivings, he hoped it would be ratified by the states and believed that the amendment process would cure its weaknesses. In the end, Clark, fearful that smaller and less wealthy New Jersey was being exploited by Congress under the Articles of Confederation, swallowed his idealism, believing taxation would be more equitable with the new Constitution. His expressed critiques of the Constitution came back to haunt him in the first federal election under the nation’s new charter.[31]

William Livingston helped decide Clark’s fate in an election so fraught with problems, New York merchant Walter Rutherfurd remarked, “Poor Jersey, is made a laughing stock of.” Historian Richard P. McCormick extensively studied the New Jersey election of 1789 and concluded:

Loose franchise requirements . . . poorly distributed polling facilities, partial election officials, lax balloting regulations, and ambiguous provisions for closing the election and counting the votes were but some of the flaws in the mechanism. There existed every opportunity for determined political managers to pile up votes in a brazenly calculated manner. Because the machinery was faulty, it cannot be said that the election represented the popular will of the people of New Jersey.

New Jersey had four seats in the House of Representatives to fill. Under the new federal Constitution, selection of House representatives bypassed the state government, going to the majority choice of eligible voters. The legislatures, however, established the ground rules for the election. An act of the New Jersey legislature established voter qualifications, polling locations, oversight and also established the governor and his Privy Council (chosen from the Legislative Council) as certifiers. Most importantly, the election of the representatives consisted of a statewide four-person slate.

New Jersey was politically bifurcated as a “result of historical, geographic, social, cultural, and economic differences between the two regions” of East and West Jersey. Both sections were united in their widespread support for the new Constitution and the belief that federal import tariffs would ease the tax burden of less wealthy New Jersey. To the chagrin of West Jersey, Abraham Clark and his fellow East Jersey representatives dominated the legislature. West Jersey’s leaders and sympathizers looked to the election of 1789 to seize back the government. In this effort, they had a Federalist ally living in Elizabethtown, Livingston’s friend Elias Boudinot. A veteran, former Continental Congress President, and Federalist, Boudinot emerged as the leader of the four-person slate preferred by West Jersey. “The Junto,” as Boudinot’s ticket was known, also included James Shureman, Thomas Sinnickson, and Lambert Cadwallader. All three had experience in government and were against the major policies advocated by Clark. East Jersey was unable to produce a unanimous four-person slate. Clark and Jonathan Dayton, the son of his friend Elias Dayton, were the two leading East Jersey candidates appearing on several four person slates.

The West Jersey faction branded the election as a choice between those who favored the Constitution and those who favored the old government. Substantive policy took a backseat to personal attacks. An organized effort to discredit and smear Abraham Clark emerged from several quarters. Just days before the polling started on February 11, Clark published a piece in the Political Intelligencer defending himself against published accusations that he was anti-Constitution. Seen as the strongest candidate, Clark was the number one target of The Junto and was also accused of feeling contempt for George Washington. Quakers were planning to sit out the election, and The Junto convinced them that Clark and Dayton were planning to impose a Presbyterian tyranny on them. Clark’s East Jersey compatriot Dayton was accused by The Junto of being a London Trader. Clark-Dayton allies fought back by spreading word that Boudinot was a corrupt politician who had stolen from the national treasury while in Congress.

The election turned into a confused hotly contested affair due to the mistake of not having a hard date for counties to report their results. The election statute only required that counties submit results when they were finished counting. This not surprisingly led to unscrupulous efforts to win. The West Jersey Junto’s operatives in East Jersey relayed ongoing vote totals to the campaign back home. Boudinot’s slate sent election inspectors around friendly counties with ballot boxes to rake in more votes, which was illegal because exact polling locations were specified by election law.

On March 3, with polling one month-old, Governor Livingston summoned a meeting of the Privy Council to sort out the election. At the time of Livingston’s meeting, county returns were still outstanding with Clark and Dayton leading the West Jersey Junto. Two of the Privy Council members favored giving them the victory with limited results reported. The other two members supported waiting until all counties reported. Livingston chose to keep the counting going. Here was the benefit of holding power. Livingston was a referee for an election involving his friend and partisan ally Boudinot.

Livingston reconvened the Privy Council on March 18, at which time Boudinot’s ticket moved into a lead with all West Jersey counties reporting. Essex county was still open, however. Clark and Dayton’s supporters, despite not having favorable math, wanted to buy more time and accordingly took to the newspapers. The East Jersey ticket was countered by published articles appealing to the patriotism of Essex County to close the polls. The Governor and Privy Council were again divided on when to call the election. Despite this, on March 19, Livingston declared the Boudinot ticket winners. He certified the results, publicly declaring that Essex County was preventing New Jersey from having representation in the incoming Congress.[32]

The contentious election was not over. James Madison wrote to George Washington who was about to start his first term as President of the United States, “In New Jersey the election has been conducted in a very singular manner . . . by a rival jealousy between the Eastern & Western divisions of the State . . . an impeachment of the election by the unsuccessful competitors has been talked of.”[33]

Essex County did not close it polls until April 27, and the day after, the “impeachment” arrived in Congress as a bundle of numerous petitions from “citizens of New-Jersey, complaining of the illegality of the election of the members holding seats in this house.” The House referred the matter to its Committee of Elections which was charged with interviewing petitioners to “receive such proofs and allegations, as the petitioners shall judge proper to offer, in support of said petition,” and those “in opposition to said petition.”On July 14, the House received the Committee of Elections report. Read and debated the next day, it was not until September 2 that the House officially declared “upon full and mature consideration, that James Schureman, Lambert Cadwalader, Elias Boudinot, and Thomas Sinnickson, were duly elected and returned to serve in this House.”[34]

[1]John Adams to Joseph Hawley, June 27, 1774, Founders Online, National Archives.

[2]Abraham Clark to Elias Dayton, June 26, 1776, Jared Sparks Collection, Harvard University.

[3]Samuel Tucker to Richard Stockton, Clark, John Hart, and Francis Hopkins, in Worthington Chauncey Ford, et al., eds. Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789 (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1906), 5:490 (JCC).

[4]Ruth Bogin, Abraham Clark and the Quest for Equalityin Revolutionary America (East Brunswick: Associated University Press, 1982), 42, 142, 163-166; Clark to Dayton, June 26, 1776.

[5]James Gigantino II, William Livingston’s American Revolution (Philadelphia: Penn, 2018), 42.

[6]Clark to Dayton, July 4, 1776, in Paul H. Smith, et al., eds. Letters of the Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789, May 16-August 15, 1776 (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1979), 4:378-379 (LOTDC).

[7]Clark to Dayton, June 26, 1776.

[8]Clark to William Livingston, July 5, 1776, LOTDC 4:391.

[9]Gigantino, William Livingston’s American Revolution, 22-23, 31, 70-71, 74-77, 84.

[10]Livingston to Tucker, July 26, 1776, in Carl Prince, et al., eds. The Papers of William Livingston, June 1774-June 1777 (Trenton: New Jersey Historical Commission, 1979), 1:107 (PWL).

[11]Livingston to Silvanus Seeley, November 26, 1779, PWL 3:233; Livingston to Seeley, December 7, 1779, PWL 3:255; Livingston to Clark, February 1, 1780, PWL 3:294.

[12]Clark to John Jay, December 21, 1778, Papers of the Continental Congress, Letters Addressed to Congress 1775-1789, Roll 93, M247, p. 287-289 (POTCC).

[13]Livingston to Nathaniel Scudder, December 24, 1779, PWL 3:278.

[14]Richard P. McCormick, “New Jersey Defies the Confederation: An Abraham Clark Letter,”The Journal of the Rutgers University Libraries, vol. 13, no. 2 (1950), 47-50; Report of Congressional Committee, September 27, 1785, JCC 29:765-775.

[15]Bogin, Abraham Clark, 125.

[16]Benjamin Thompson to Livingston, October 22, 1785, PWL 5:208-209.

[17]“To tarnish the glory,” National Virtue and the Constitutional Convention September 21, 1784—October 1787, PWL 5:151-152.

[18]The Political Intelligencer and New Jersey Advertiser, December 14, 1785.

[19]The Political Intelligencer, December 21, 1775.

[20]New Jersey-Gazette, January 9, 1786.

[21]The Political Intelligencer, January 11, 1786.

[22]Bogin, Abraham Clark, 78-83.

[23]New Jersey-Gazette, January 16, 1786.

[24]Bogin, Abraham Clark, 160-161.

[25]“The True Policy of New Jersey, Defined,” in Howard L. Green ed., Words That Make New Jersey: A Primary Source Reader (Trenton: New Jersey Historical Commission, 1995), 67-69.

[26]General Assembly Meeting, February 20, 1786, in Isaac Collins, ed., Journal of the Votes and Proceedings of The Tenth General Assembly of the State of New-Jersey, 2nd sitting (Trenton: Isaac Collins, 1786), 12-13. (JV&P).

[27]Meeting of Congress, March 7, 1786, JCC 30:96.

[28]General Assembly Meeting, March 9, 1786, JV&P 43-44.

[29]Credentials of the State of New Jersey, Journal of the Acts and Proceedings of the Convention, Assembled at Philadelphia (Boston: Thomas B. Wait, 1819), 26.

[30]Gigantino,William Livingston’s American Revolution, 189-191.

[31]Clark to Thomas Sinnickson, July 23, 1788, in John P. Kaminski, et al., eds. The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution Digital Edition (Charlottsville: University of Virginia, 2009).

[32]Richard P. McCormick, “New Jersey’s First Congressional Election, 1789: A Case Study in Political Skullduggery,” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 6, no. 2 (1949), 238-250.

[33]James Madison to George Washington, in Gillard Hunt, ed., The Writings of James Madison (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 5:329-330.

[34]House of Representatives, April 18-19, 1789, Journal of the House of Representatives (Francis Childs & John Swaine: New York: 1789), 25-28, 54, 105, 120.

Recent Articles

That Audacious Paper: Jonathan Lind and Thomas Hutchinson Answer the Declaration of Independence

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Recent Comments

"Eleven Patriot Company Commanders..."

Was William Harris of Culpeper in the Battle of Great Bridge?

"The House at Penny..."

This is very interesting, Katie. I wasn't aware of any skirmishes in...

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...