Located at the junction of the Acushnet River and thedeep waters of Buzzards Bay, the New Bedford and Fairhaven area became a hub for whaling, fishing, and trading during Colonial times. Whaling, in particular, became the main driving force for the area’s economy after Capt. Christopher Hussey of Nantucket began hunting sperm whales in 1712.[1]

Forty to fifty whaling ships called New Bedford home at the start of the American Revolution, but the industry ground to a halt after hostilities began.[2] By the end of 1777, however, New Bedford was the only major port north of the Chesapeake still in rebel hands, so it quickly became a vital hub for the burgeoning fleet of privateers the rebels had been authorizing. The buccaneers stored the cache of captured British goods in local warehouses and later distributed it to the American Army. In September1778, British Gen. Sir Henry Clinton ordered Maj. Gen. Charles Grey to lead a 4,500-man expedition to eliminate this problem. While the nearly forgotten raid on New Bedford, Fairhaven, and Martha’s Vineyard by British troops would prove successful for the British in the short term, the brutality of their invasion would hurt their cause in the long term.

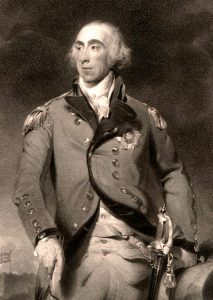

Charles Grey, 1st Earl Grey (1729–1807) led the expedition. Grey had served with distinction during the Seven Years’ War in Europe and Havana, Cuba, retiring as a lieutenant colonel in 1763. In 1772 he was promoted to full colonel, served as aide-de-camp to King George III. After war broke out in American he was promoted to major general, leading a brigade during the Battle of Brandywine in 1777.[3]

Americans remember him most for his controversial leadership of British troops during the Battle of Paoli in September 1777. During the British campaign to conquer Philadelphia, Grey learned of an American division of 1,500 Continental troops under Gen. Anthony Wayne along the Schuylkill River, south of Paoli, Pennsylvania, whose assignment was to harass and delay the British advance.[4] In a bold move, Grey ordered his troops, consisting of the 2nd Battalion of Light Infantry, the 42nd and 44th Regiments, to remove the flints from their muskets, preventing inadvertent gunfire that might eliminate the element of surprise. His men instead relied on their bayonets and swords for their nighttime attack. The battle became a rout as the British surprised the sleeping Americans before they could establish any organized defense, causing the majority to flee in panic. The skirmish left an estimated 53 dead, 113 wounded, and 71 missing or captured Americans compared to four killed and seven wounded British soldiers.

The Americans considered the strategy barbaric, referred to the “battle” as the Paoli Massacre, and eventually nick-named the general “No-Flint Grey.” The British reaction, on the other hand, reflected their struggle dealing with the Americans throughout the war. British commanders in chief Sir William Howe and Sir Henry Clinton believed the only way to regain the colonies was to “gain the hearts & subdue the minds of America.”[5] Thus they expected their troops to practice restraint in dealing with the colonists. But many of their subordinates believed in a “Fire and Sword” approach to bludgeon the Americans back into submission. It was a struggle throughout the upper echelon of English society, as related by one historian:

James Murray, a British historian who authored An Impartial History of the War in America in 1783, made the following observations concerning the “massacre” aspect of the Battle of Paoli: “General Grey conducted this enterprise with equal ability and success though perhaps not with that humanity which is so conspicuous in his character. . . . A severe and horrible execution ensued. . . . The British troops and the officer who commanded them gained but little honor by this midnight slaughter. It showed rather desperate cruelty than real valor.”[6]

The struggle between winning the colonists back through reconciliation or waging a form of the brutal Wallenstein Kontribution, as practiced in the bloody Thirty Years’ War, would plague the British throughout the conflict.[7] General “No-Flint” Grey would become an example of British brutality to the Americans and a picture of restraint and brilliant leadership to the British during his campaign to seize livestock and destroy the privateer bases around Martha’s Vineyard.

After France entered the war in August 1778, the Americans and their new allies planned an attack on the British garrison in Newport, Rhode Island. Admiral Comte d’Estaing led the French naval and armed forces, and Gen. John Sullivan led the American troops. Responding to the threat, British Gen. Sir Henry Clinton ordered Grey to prepare 4,000 soldiers in New York to board transports to reinforce Newport’s defense. Simultaneously, the British fleet under Admiral Lord Richard Howe set sail from New York to engage the French fleet. On August 10, D’Estaing sailed out of Newport Harbor intending to drive Howe’s fleet away while Sullivan laid siege on Newport.

As the two navies prepared for battle, a powerful storm struck, driving the fleets apart, damaging D’Estaing’s ships and causing him to sail for Boston to make repairs, abandoning Newport. The loss of support from the French fleet forced Sullivan to retreat, ending the Siege of Rhode Island.

Following Sullivan’s retreat, Generals Clinton and Grey scouted New London, Connecticut, for possible targets. Seeing nothing worth the risk, Clinton ordered Grey, in the words of Thomas Jones, a Loyalist judge, “to exterminate the nests of some rebel privateers, which abounded in the harbors, rivers, and creeks about Buzzard’s Bay, in the old colony of Plymouth.”[8]

The first “nest” Grey went to exterminate was New Bedford, home of whaling, fishing, and cargo ships. Guarding the town was Fort Phoenix, a small stronghold with eleven artillery pieces. Its thirty-two-man garrison fired a few rounds on the British fleet as it approached, then spiked the canons and fled before Grey’s troops landed.

Grey sailed up the Acushnet River toward New Bedford and Fairhaven on September 4, landing at Clark’s Point on the western shore later that evening after being piloted by a Dartmouth Tory named Joe Castle. Grey’s troops spent the rest of the night and part of the next day putting twenty-one warehouses along with much of their contents, seventy-some-odd vessels, eleven private houses, and several piers. The soldiers marched north, crossed the Acushnet River over a bridge of small boats, then headed south along the river’s eastern shore on September 6, burning Fairhaven’s warehouses and piers, and finally destroying Fort Phoenix.

Many of the burned ships were captured British “prizes” taken by the privateers operating out of New Bedford and Fairhaven. British Army Captain Frederick Mackenzie wrote,

this conflagration was so massive that it lit up the night sky at Newport, more than twenty miles away. A great fire appeared towards Bedford last night, showing that General Grey has succeeded in destroying the enemy’s shipping and store at that place.[9]

Later, local officials would put the town’s damage at $422,680, a considerable sum in 1778. The fort’s cannons were salvaged at a later date.

Whether the soldiers meant to destroy houses in New Bedford is unknown. According to Capt. John Peebles, commanding a grenadier company on the expedition, the troops had been given orders not to burn down civilian houses.[10] That no homes on the Fairhaven side of the bay caught fire suggests that wind blowing from the east pushed the flames in New Bedford inland, igniting homes, while on the Fairhaven side fires were pushed towards the sea. It may have been the wind, not the British, that was the culprit for the loss of private homes.

Grey reported the operation to Clinton like this:

I proceeded without loss of time to destroy the Vessels and Stores in the whole extent of Accushnet River (about 6 miles), particularly atBedford and Fair Haven, and having dismantled and burnt a Fort on the East Side of the River, mounting 11 pieces of heavy Cannon with a Magazine &. Barrackscompleted the Re-embarkation before noon the next day.[11]

He further reported that his troops destroyed eight ships weighing between 200 and 300 tons: six vessels, each carrying between ten and sixteen cannons, and seventy other ships that included several sloops, schooners, whale-boats, and others. The warehouses burned at Bedford, McPherson’s wharf, CransMills, and Fairhaven containedsubstantial quantities ofrum, sugar, molasses, coffee,tobacco, cotton, tea, medicines, gunpowder,sail-cloth, cordage, and two large ropewalks.

There are conflicting accounts of what actually happened in Fair Haven on September 6. Captain Peebles wrote that after the invading British troops had received some militia “popping shots,” and the soldiers “killed some & took some prisoners”; he gave no further details of the day.[12] British Major John Andre, the man later hung for assisting Benedict Arnold’s treason, wrote in his diary of a few men wounded by “people lurking in swamps and behind stone fences” and that “three or four men of the enemy were found bayonetted, one an officer,” during the raid.[13]

A very different picture was given by an author named Timothy Dwight who wrote about the raid just after the war. He recounts that local militia leader Maj. Israel Fearing, having stationed his 140 militia men behind fences, walls, and trees, told them to wait to fire upon the British until they were well within the town. Then the brave but raw citizen-soldiers rose from their hiding places and gave the invaders a murderous volley. So unexpected and deadly was the militia’s defense that the British turned and fled back to their boats, leaving several blood trails. Because of the stout resistance by its militia, according to Dwight, Fair Haven only lost a few buildings.[14]

On September 8, the New Bedford militia prevented a detachment of British Marines from reentering the town, saving the remaining warehouses, wharves, and ships from destruction. The following day, the ships carrying Grey’s troops began to move towards Martha’s Vineyard.

While Martha’s Vineyard had no large harbors or towns, its farmers did have enough livestock to feed an army. During a March 29, 1777 town meeting, one of the residents stood before the general court and stated: “The British come here and pay you good prices for your sheep, cattle, and provisions. You can take this money and help our army in many ways. If you refuse, they will take everything as they can land anywhere, anytime, and you haven’t any way to protect yourselves.”[15] The speaker urged the residents to remove the island’s livestock to prevent them from being captured by the British. The general court voted against the suggestion. Eighteen months later, General Grey’s raiders showed just how foolish the council had been.

After leaving New Bedford, Grey sent a message to Clinton requesting transport for the animals he intended to seize. On September 10, Grey landed in Martha’s Vineyard to begin the operation. A committee of three citizens led by Col. Beriah Norton of the island’s colonial militia approached Grey’s ship, the Carysfort, to learn his intentions. Grey demanded the islanders immediately surrender 10,000 sheep, 300 oxen, all the citizen’s weapons, and all public funds, or his troops would take them by force. Seeing the futility of resistance, Norton agreed to Grey’s demands. Grey put Norton in charge of collecting the booty.

By September 12, the townsfolk had only provided the fleet with 6,000 sheep and 130 oxen. To expedite the process, Grey landed small groups of troops to destroy vessels and harass the locals. By September 14, the livestock was collected and delivered, then loaded onto twenty waiting ships for transport to Newport, Rhode Island. According to the islanders, Grey promised reimbursement for the confiscated animals from Clinton later, though Grey in his report to Clinton said only that he requisitioned them.[16]

Charles Edward Banks, a late nineteenth-century historian, recorded the following event as having happened during the British stopover:

One day, the British arrived suddenly at the home of Thomas Waldron, who had two barrels of powder in the house. He immediately rolled them near the fireplace, where a good fire was blazing, and told his two daughters to sit on them and knit while the soldiers were in the house. The large skirts of the time covered the barrels completely. It can be imagined how the two young ladies felt, especially when one of the soldiers started to play with a ball of yarn.[17]

General Grey documented the amount of booty he took and things he destroyed from Martha’s Vineyard: Dozens of vessels, including one 150-ton brig, a 70-ton schooner, and 23 whale-boats taken or destroyed. A quantity of plank taken. A salt work was ruined, and a considerable amount of salt was taken along with 388 muskets, with bayonets, pouches, etc., some gunpowder, and a large amount of lead. Fifty-two tons of hay, delivered for forage during the return voyage, and £1000 sterling, was also confiscated. Grey’s expedition seized 315 cattle and 10,574 sheep to feed the British army in Rhode Island and New York.[18]

Grey, along with his men and the livestock, left Martha’s Vineyard on September 15 and arrived in Whitestone, Queens County, Long Island, on the 17th. His report recorded one British soldier killed, four wounded, and sixteen missing on the campaign, as well as four Americans killed and sixteen captured, the latter of whom he later exchanged for his own captured men.

Upon receiving Grey’s report, Sir Henry Clinton wrote, “I hope it will serve to convince these poor deluded people that that sort of war, carried to a greater extent and with more devastating, will sooner or later reduce them.”[19]

Beriah Norton petitioned Clinton and later Clinton’s successor Sir Guy Carleton for £10,000 to compensate for the livestock. He would travel to New York and London to present his case, and eventually, in 1783, Carleton paid £3,000 against these claims.[20]

Charles Grey, who was one of the most successful British generals of the war, would use his “no-flint” tactic on Americans a few weeks later, on September 27, 1778, during the Baylor Massacre in which the British killed, wounded, or captured 69 out of 116 American cavalry soldiers and officers.[21] Grey soon after returned to England to be knighted into the Order of the Bath, then promoted to commander of the British forces in North America, but the war ended before he took over. He later became famous as the conqueror of Martinique and died in 1807 at the age of seventy-eight.[22]

Grey’s Raid is another example of opposing narratives of one event. In addition to the narratives, the contemporary perspectives also contrasted greatly. To the Americans, the resistance displayed at Fair Haven by Major Fearing was not only a point of pride; it saved the town and ships from destruction. But to the British, the Battle at Fair Haven was “a few men wounded by people lurking in swamps and behind stone fences.”[23] Far more important, though, is that before Grey commandeered their sheep and cattle, the people of Martha’s Vineyard had gone to great lengths to remain neutral in the rebellion. But how neutral they remained after having nearly all of their food taken from them, with winter fast approaching, is a different story. Whether intentional or not, each act like this brought more colonists over to the rebel cause or reduced the draw towards the Loyalist side.

[1]“Timeline 1602 to Present – New Bedford Whaling Museum,” www.whalingmuseum.org/learn/research-topics/regional-history/timeline-1602-to-present/.

[2]Clifford W. Ashley, The Yankee Whaler (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1926), 37-38.

[3]“Charles Grey, 1st Earl Grey,” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Grey,_1st_Earl_Grey.

[4]Thomas J. McGuire, Battle of Paoli(Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000).

[5]Andrew Jackson O’shaughnessy, “‘To Gain the Hearts and Subdue the Minds of America’: General Sir Henry Clinton and the Conduct of the British War for America,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society158, no. 3 (2014): 199–208.

[6]Thomas J. McGuire, Battle of Paoli: The Revolutionary War “Massacre” Near Philadelphia, September 1777(Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2006), 125.

[7]Stephen Conway, “To Subdue America: British Army Officers and the Conduct of the Revolutionary War,” The William and Mary Quarterly43, no. 3 (1986): 381–407.

[8]Thomas Jones, “History of New York During the Revolutionary War,” in History of New York During the Revolutionary War, vol. I (New York: Trow’s Printing & Bookbinding Co., 1879), 278.

[9]Paul David Nelson, Sir Charles Grey, First Earl Grey: Royal Soldier, Family Patriarch(London: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1996), 65.

[10]John Peebles, John Peebles’ American War: The Diary of a Scottish Grenadier, 1776-1782(Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1997), 214.

[11]John André, Journal of Major André(Tarrytown, NY: William Abbatt, 1930), 94.

[12]Peebles, John Peebles’ American War, 216.

[13]André, Journal of Major André, 89-90.

[14]Timothy Dwight, Travels in New-England and New-York(London: William Baynes and Son, 1823), 3:60–62.

[15]Henry Franklin Norton, Martha’s Vineyard: Historical, Legendary, Scenic(Hartford: The Pyne Printery, 1923), 17.

[16]Arthur R. Railton, “Islanders and the Revolution: Grey’s Raid, 1778,” The Dukes County Intelligencer Vol. 48 No. 1 and 2 (Winter 2006-2007): 10.

[17]Charles Edward Banks, The History of Martha’s Vineyard, Dukes County, Massachusetts (Boston: George H. Dean, 1911), 1:72.

[18]Arthur R. Railton, “The Story of Martha’s Vineyeard: How We Got to Where We Are. Chapter Four: Grey’s Raid: An Attack or a Shopping Expedition,” The Dukes County Intelligencer Vol. 44 No. 3 (February 2003): 141-142.

[19]Railton, “Islanders and the Revolution: Grey’s Raid, 1778,” 8.

[21]Baylor Massacre, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baylor_Massacre.

[22]“Charles Grey, 1st Earl Grey,” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Grey,_1st_Earl_Grey.

[23]André, Journal of Major André, 89.

2 Comments

Great article and use of eyewitness narratives to support your thesis. I had always read that the British invaded, burned and sacked New Bedford area because bad winds prevented them from getting into New London harbor-another equally important patriot nest. Of course, New London would be a much later target of an equally brutal attack by Arnold. To live in these coastal New England communities for these eight long years of war was extremely stressful.

With reference to the description of General Grey’s night attack against Anthony Wayne’s troops near the Paoli Tevern in September 1777, which sets the scene for this account of the New Bedford operation, since the “battle of Paoli’ still tends to hover on the fringes of folklore, it might be worth considering these few details. Word of Wayne’s force lurking in the woods to the rear of the British camp reached General Sir William Howe, and it was he who directed Grey to mount an attack to foil this threat to his columns. Grey did not order troops to remove flints from their muskets, merely to march unloaded in order to avoid a premature discharge warning the enemy, but any who could not extract the munitions from loaded muskets should then remove the flints. With Grey’s permission, the 2nd Light Infantry in the van marched with loaded weapons, their CO, Major Hon. John Maitland, having guaranteed the compliance of his men.

Most importantly perhaps, Wayne’s Pensylvanians were not sleeping when Grey’s troops attacked. The alarm had been raised and the battalions formed up and preparing to march when the 2nd Light Infanry burst from the woods on their right and a running fight with subsequent rout ensued. For some reason the myth that grew up of the Pennsylvanians _were_ caught sleeping and mercilessly slaughtered seems for some to have been a preferable narrative to that of their being defeated when formed up and alert to the possibility of attack. Demonising the King’s troops at the expense of Wayne’s reputation and that of his men perhaps was of more value to the Patriot propaganda effort.