Despite the imperative nature of his unusual name, Remember Baker has garnered significantly less historical attention than fellow Green Mountain Boys Ethan Allen and Seth Warner. Baker seemed destined for an important role in the Revolutionary War, but his life was cut short in an August 22, 1775 incident across the Quebec border. As a result of this “unhappy affair,” Remember Baker’s most significant Revolutionary War legacy was the diplomatic crisis caused by his “imprudence” on the very eve of the Canada invasion. Previously neglected documentary material only reinforces Baker’s responsibility for the controversial incident that resulted in his death.[1]

Remember Baker had emerged as a Green Mountain Boys leader in the early 1770s, during the land-rights struggle in what is now Vermont. He moved from Connecticut to the disputed New Hampshire Grants region with his cousins, Allen and Warner. Together they settled, speculated, fought, and established de facto control that subverted New York’s lawful authority there. Baker was indomitable in this effort, a French and Indian War veteran, “about 5 feet 9 or 10 inches high, pretty well sett, something freckled in his face,” who had once killed a bear with only a hatchet. Friends and allies considered him “a Man of Courage and Integrity and well beloved in that Country,” but not everyone shared those sentiments.[2]

New Yorkers ranked Remember Baker as “one of the worst men among the Riotors” in the Grants region. He terrorized unwanted settlers with threats, property destruction, and corporal punishment. When a posse tried to arrest and deliver him to New York authorities in 1772, Baker lost a thumb to a sword stroke in the ensuing struggle before being rescued by compatriots. After this incident, he flaunted the missing digit as a badge of honor and authority while enforcing insurgent rule as a judge and militia captain. New York government officials grew increasingly exasperated with the Green Mountain Boys’ relentless challenge to their jurisdiction. By March 1774, Gov. William Tryon had formally requested military support and offered £100 rewards for the apprehension of Ethan Allen or Remember Baker. The Grants conflict seemed to be reaching a climax.[3]

The spark of Revolutionary War in 1775 completely recast the region’s politics. Shortly after Lexington and Concord, the Green Mountain Boys allied themselves with New England patriots to take British Fort Ticonderoga on May 10. Captain Baker and his militia company arrived too late for that conquest, but helped capture Crown Point a day later. Riding this wave of victory and eager to strengthen their position in the American Cause, the Green Mountain Boys selected Ethan Allen, Seth Warner, and Baker to represent them to the Continental Congress—although Baker does not seem to have joined his cousins on their Philadelphia trip.[4]

The Green Mountain Boys’ political reorientation put them in some strange company, especially when Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler took command of the Continental Northern Army. The general was a major New York landholder and assembly member—someone with clear political interests on his colony’s side of the Grants struggle; yet as fellow patriots, Baker and Schuyler apparently overlooked past conflict. By mid-July 1775, the Green Mountain Boys captain was voluntarily scouting the northern end of Lake Champlain for the general. With his “Bush fighting” skill and initiative, Baker proved to be a valuable intelligence source for military developments in Canada.[5]

In another unexpected twist that summer, New York reluctantly accepted a Continental Congress request to enlist a regiment of Green Mountain Boys. Cautious Grants township leaders, however, did not elect either Ethan Allen or Remember Baker as officers for the unit, which was commanded by Seth Warner. Nevertheless, Baker continued his reconnaissance missions around—and sometimes across—the New York-Quebec province line. Schuyler referred to him as “Captain Baker of the unenlisted Green Mountain Boys,” differentiating him from peers in the new Continental regiment.[6]

The Unhappy Affair

The stage for Remember Baker’s final act was set on July 27, as he prepared for another Lake Champlain mission. That day, Baker wrote to General Schuyler, proposing an aggressive scheme to ambush enemy forces from Canada, using a light boat to lure them into range of a hidden bateau armed with swivel guns. The general’s response was recorded in the Orderly Book of Philip John Schuyler in the Huntington Library collections. Schuyler agreed to send Baker north again, but provided explicit instructions to ensure the captain’s actions reflected Continental strategic objectives for Canada.[7]

you are to proceed down the Lake and scout the coast in quest of any parties of regular Troops that may be sent by General Carlton to reconnoiter, if you should fall in with any you will use your Best Endeavours to take or Destroy them. . . . Should you meet with any Canadians or Indians you will Treat them with the greatest Kindness and Invite them to Come and see me. . . . You will not go beyond the Limits of this province with your party but as I wish to have Intelligence of what is Doing at St Johns you are at Liberty with a few of your party to go by Land and reconnoiter that place. . . . You will on all such act with prudence and according to the best of your Judgment. [author’s emphasis][8]

Schuyler’s specific restraints and different rules of engagement for British regular troops or Canadians and Indians would prove critical one month later when the general found himself dealing with the undesired consequences of Baker’s mission.

The Orderly Book also contained Schuyler’s supporting orders for the mission. Captain Baker was authorized to “take as many men of his own chusing” from Crown Point to form a detachment of twenty-five men, and the commander there was directed to issue them twenty days’ provisions. The detachment embarked on the Continental schooner Liberty, which towed Baker’s bateau and light boat north on Lake Champlain.[9]

Patrolling near the province line, Liberty served as a mobile base for Baker’s reconnaissance forays. By mid-August, Baker and the schooner had been out longer than expected, so officers sent additional provisions from Crown Point. Uriah Cross, a soldier in James Easton’s Massachusetts Regiment, was in this resupply party and joined Baker’s detachment after their rendezvous.[10]

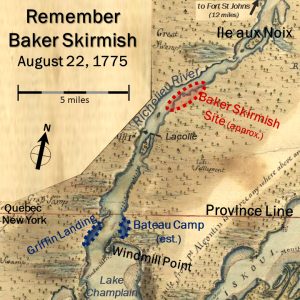

On August 20, Baker also welcomed Pvt. Peter Griffin aboard Liberty. He was another soldier from Easton’s Regiment, who had just completed a separate lake scouting operation. Baker decided to send Griffin and a friendly Odanak (St. Francis Abenaki) across the province line by land to reconnoiter British Fort St. Johns, per Schuyler’s orders. At dawn the next day, Baker and four men, including Uriah Cross, escorted the scout duo from Liberty in the two boats. Griffin and his partner disembarked on the western shore, near modern Rouse’s Point, New York, south of the province line. As the scouts set out for a long, swampy trek to the fort, Griffin said that Baker proceeded down the Richelieu River, which flows north out of Lake Champlain, “in a boat to the Isle aux Noix, and Did Determine to Intercept the Scouts of the Regulars there.” Ile aux Noix was nine miles north of the province line, indicating that Baker was intent on ignoring Schuyler’s orders against operating “beyond the Limits of this province.”[11]

There is no record of Baker’s activities for the rest of that day. According to the captain’s cousin and close associate Ira Allen, “in the silent watch of the night,” Baker’s party landed on the east shore of the lake. Their camp was back on the New York side of the line, probably near Windmill Point (Vermont). At dawn on August 22, the captain and his four men “secured” the heavy bateau on land before embarking in their light boat. They paddled north to cross the province line.[12]

Around the same time, Lt. Edward Pearee Willington of the 26th Regiment of Foot led a party of eight native allies from British Fort St. Johns on a regular border patrol, accompanied by Indian Department interpreter Claude de Lorimier. They were looking for rebel spies and indications of a coming invasion. Like all of the king’s Indian allies, this party was under Gov. Guy Carleton’s strict orders not to operate across the province line. Willington took four men in one canoe to scout the west shore; Canadian interpreter Lorimier went east with four Kanesatake warriors in another canoe.[13]

Claude de Lorimier and his party disregarded Carleton’s general orders that day and patrolled south of the province line. Concealed among low tree branches and reeds on the shoreline, the Canadian interpreter “saw the famous Captain Baker, but . . . was obliged to come back without attacking the party because we didn’t want to start any trouble on the other side of the line.” Oblivious to the potential ambush, Baker and his Americans continued north. Lorimier and his warrior companions kept exploring southward until they found Baker’s cached bateau on the shore, hidden under branches. The party launched the armed boat and paddled it toward Canada.

Remember Baker, meanwhile, had crossed the province line and landed on the east shore, five miles into Canada. The captain “sat down and sharpened his flint”—he was “a curious marksman” who “always kept his musket in the best order possible.” At this most unfortunate moment, the captain spied “a party of Indians . . . approaching the point of land where he was”—and they were in his own armed bateau! Baker ordered his four men to “be concealed and ready.”[14]

Details of the fatal affair that followed come from a number of sources.[15] General Schuyler provided the most detailed contemporary reports, undoubtedly informed by American survivors. Participants Claude de Lorimier and Uriah Cross wrote first-hand accounts many years after the fact. The most comprehensive version of the violent encounter came from Baker’s cousin Ira Allen in his 1798 History of Vermont. This second-hand narrative aligns with details in the various primary sources and offers additional context for the complicated but fleeting encounter:

when the Indians came near [, Baker] hailed them, and desired them to give up his boat in a friendly manner, there was no war between the Indians and the Americans . . . the Indians showed no signs of giving up the boat, whereupon Baker ordered them to return his boat, or he would fire upon them. An Indian in the boat was preparing to fire on Baker, who attempted to fire before hand with him, but his musket missed fire, owing to the sharpness of his flint, which hitched on the steel; he recover his piece, and levelled it at the Indian, at which Instant the Indian fired at him, one buck shot entered his brains and Baker fell dead on the spot. His men fired on the Indians and wounded some, but the boat was soon out of gun shot.[16]

Baker’s spur-of-the-moment decision to fight for his lost boat was a direct contravention of Schuyler’s strategically deliberate orders to treat Indians and Canadians “with the greatest Kindness.”

After the exchange of volleys, Lorimier reported “all was silent.” He and his Kanesatake companions, one wounded in the neck and another in the thigh, left in haste for Fort St. Johns aboard the captured bateau. A contemporary Quebec newspaper account reported, “it being almost dark they could not see whether or not they had killed or wounded any of the Enemy.”[17]

The next day, British Capt. Andrew Gordon led “25 Indians, 33 Soldiers, and 5 or 6 Volunteers” from Fort St. Johns to the skirmish site. They found Baker’s body and collected his papers. Native warriors scalped Baker, cut off his head, and removed at least one finger, carrying the severed body parts back to Fort St. Johns. There, the warriors erected Baker’s head on a pole before taking it to Montreal. According to Ira Allen, British officers eventually bought the head from their Native allies and had it buried with the body back at the skirmish site.[19]

Immediate Responses and Legacy

Baker’s papers provided British government officials with important intelligence on rebel scouting efforts around Fort St. Johns and incriminated several American contacts in Canada. The commander of Fort St. Johns was even ordered to arrest one of Baker’s contacts at Lacolle, who had been “very kind & free in telling” the captain “all the proceedings of the Regulars.” Loyalists also hoped that this opening act of violence, north of the province line, would inspire Canadians and Indians to decisively commit themselves to the British side of the war. The locals largely remained unaligned though, even as false rumors spread that Baker had orders from Schuyler “to give no quarter to Canadians or Indians.”[20]

On the same day that the Baker affair took place, Peter Griffin and his Odanak scout companion completed their Fort St. Johns reconnaissance. When they reached their original landing spot, they did not see Baker. Instead, they “saw Ten Indians Coming in a Canoe from the East side of the River towards them.” Griffin and his partner fled into the woods to avoid capture and spent the night with a friendly settler nearby. The next morning, the Odanak’s father found and delivered them back to Liberty. Griffin had vital intelligence for General Schuyler—the two British warships at Fort St. Johns were very near completion. American naval superiority on the lake was at risk. The Canada invasion could not begin soon enough. The schooner expeditiously set sail to deliver this time-sensitive information. Everyone aboard was still oblivious to Baker’s fate. When Griffin reached Ticonderoga on August 25, General Schuyler was away at a crucial Six Nations Indian treaty conference in Albany. The deputy commander, Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery, heard Griffin’s report and promptly set the invasion into motion.[21]

Schuyler received word of the Baker affair by August 31, after the survivors had made their way back to Crown Point. The captain’s unauthorized violence against Natives took place at the very moment when Continental officials were trying to secure the powerful Six Nations’ neutrality. Schuyler had to limit the potential political damage. Erroneous information from Canada raised the stakes even further. The general was led to believe that Baker’s party had killed two of the British-allied Native scouts—and the dead were reportedly from the village of Kahnawake, the central council fire of the Seven Nations in Canada. The Continentals were desperately hoping that confederacy would also avoid taking sides in the coming invasion. If Baker actually had killed Kahnawakes, Schuyler justifiably feared it might drive their nation to take up arms with the British.[22]

Schuyler shared all of this unfortunate news in letters to George Washington, Connecticut Gov. Jonathan Trumbull, and his fellow Continental Indian commissioners in Albany. Since the commissioners were still conducting treaty business with Six Nations chiefs, they were in the best position to assess and limit the diplomatic damage. Schuyler provided them all available details and emphasized that Baker had acted against express orders. He concluded, “What the consequence of Baker’s imprudence will be is hard to foresee.” Without advocating specific actions, Schuyler advised, “It behooves us . . . to attempt to eradicate from the minds of the Indians any evil impressions they may have imbibed from this mortifying circumstance.”[23]

Schuyler joined his army for the Canada invasion, but continued working to limit the impact of “the intemperate heat and disobedience of Captain Baker.” After crossing the province line and setting up camp at Ile aux Noix on September 5, the general published a circular letter to the Canadians and Indians. It explained that the Americans had come to help, rather than fight them. Specifically addressing Baker’s actions and condoling the Seven Nations, Schuyler wrote: “If any of them have lost their lives, I sincerely lament the loss; it was done contrary to orders, and by scoundrels ill-affected to our glorious cause; and I shall take great pleasure in burying the dead, and wiping away the tears of their surviving relations, which you will communicate to them.” Following Native protocols, he promised to do this through “an ample present.”[24]

Back in Albany, the ink on the Six Nations treaty was barely dry when the Indian commissioners delivered an unvarnished account of the “melancholy news” to the chiefs. This was in accordance with treaty terms that encouraged open and honest communication. Six Nations chiefs were ultimately persuaded that it was “meerly an unfortunate accident.” At the commissioners’ request, four Oneida warriors agreed to visit Kahnawake to deliver news of the Albany treaty and explain the facts of the Baker incident. In mid-September, the Oneidas reached Canada at a critical point in the invasion. Their messages, reinforced by Schuyler’s diplomatic gifts, ensured that the Seven Nations confederacy remained neutral for the rest of the year. With essential Native diplomatic assistance, Continental authorities had managed to avert catastrophic repercussions from the Remember Baker affair.[25]

In the immediate aftermath, Baker’s death received relatively little popular notice. A couple of early articles described what little was known of the engagement. After word spread about the desecration of Baker’s corpse, a few more pieces sought to inspire patriotic vengeance for the “base and savage conduct” of the British and their Native allies. Then the story effectively disappeared for twenty-four years. Ira Allen brought it back to light in his 1798 History of Vermont, which included the most detailed narrative of the affair. Allen accurately noted that “Captain Baker was the first man killed in the northern department.” His conclusion that Baker’s “death made more noise in the country than the loss of a thousand men towards the end of the American war” appears to have been a substantial exaggeration, though, based on what is reflected in contemporary written records.[26]

The Baker affair continued to receive scant attention through the 1800s. When the occasional historian or biographers told the story of Baker’s death, they most often used it as a concluding point for their more detailed recitations of his Green Mountain Boys exploits. An early twentieth-century surge of patriotic commemoration brought a slightly more enduring attention to the captain’s wartime contributions. Initially, Remember Baker’s “sacrifices and valor” were honored in a single line on a Lake Champlain Tercentenary memorial plaque at Isle La Motte, Vermont in 1909. Twenty years later, the Vermont Society, Sons of the American Revolution erected a Baker-specific monument in Noyan, Quebec, the product of almost a quarter century of research and cross-border lobbying. Its bronze tablet read: “Captain Remember Baker, Vermont pioneer and leader of the Green Mountain Boys was killed near this spot by Indians while on a scouting expedition in Canada in the War of the American Revolution,” and it repeated Allen’s hyperbolic quote, “His death made more noise . . .” Overall, Baker’s wartime contributions and death remain obscure historical points.[27]

The story of Remember Baker’s fatal “unhappy affair” does serve to illuminate his influence in northern politics up to the time of his death. It also shows the dangers that seemingly minor, rash tactical decisions—like fighting to recover a lost boat—can pose to strategic efforts. The captain’s Vermont settlement and military contributions are worth remembering; but General Schuyler, the Continental Indian commissioners, and key Native diplomatic partners also deserve considerable credit in this event. By actively averting a strategic political catastrophe, they ensured that Remember Baker did not become a better known and infamous figure in American Revolutionary War history.

[1]“Extract of a Letter …, Sept. 5,” New-York Gazette, September 11, 1775; Philip Schuyler to George Washington, August 31, 1775, Peter Force, ed., American Archives. 4th Series [AA4] (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1837–53),3: 467.

[2]“100 Dollars Reward,” Connecticut Courant, April 27, 1773; Ira Allen “Autobiography [1796],” in James B. Wilbur, Ira Allen, Founder of Vermont: 1751-1814, vol. 1 (Boston: Houghton and Mifflin, 1928), 9, 11-12.

[3]“Account of the Temper of the Rioters …,” April 15, 1772, Documentary History of the State of New-York, E. B. O’Callaghan, ed. (Albany, 1851), 4:776; “William Tryon … A Proclamation,” [March 9, 1774], New-York Gazette, March 28, 1774.

[4]Ira Allen, History of the State of Vermont…, (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1969; reprint of The Natural and Political History of the State of Vermont…, London, 1798), 43-44; Letter from the Officers at Crown Point and Ticonderoga to the Continental Congress, June 10, 1775, AA4 2:957-58.

[5]An Account of the voyage of Captain Remember Baker, begun the 13th day of July …, July 26, 1775, AA42: 1735.

[6]Schuyler to Commissioners for Indian Affairs, August 31, 1775, AA43:493.

[7]Baker to Schuyler, July 27, 1775, Philip Schuyler Papers [PSP], New York Public Library [NYPL], digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5d144f00-84e2-0134-bce2-00505686a51c.

[8]Philip Schuyler Orders to Capt. Remember Baker, July 27, 1775, Orderly Book of Philip John Schuyler, 1775, June 28 – 1776, April 18, Huntington Library [Orderly Book, Huntington Library].

[9]Schuyler to the Commanding Officer at Crown Point, July 27, 1775, Orderly Book, Huntington Library.

[10]Uriah Cross, “Narrative of Uriah Cross in the Revolutionary War,” ed. Vernon A. Ives, New York History: Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association 63, no. 3 (July 1982): 279-294. 285; Richard Montgomery Examination of Peter Griffin, August 25, 1775,AA4 3:670.

[11]Examination of Peter Griffin, August 25, 1775, AA4 3:671.

[12]Allen, History of Vermont, 45.

[13]Lorimier said he was “patrolling with five Algonquians.” Based on context, they were probably Arundaks, one of three different nations at Kanesatake village, twenty-five miles west of Montreal; Claude de Lorimier, At War with the Americans: The Journal of Claude-Nicolas-Guillaume de Lorimier,transl. and ed., Peter Aichinger (Victoria, BC: Press Porcepic, 1987),28.

[14]Allen, History of Vermont, 45; Cross, “Narrative,” 285. The most precise contemporary description of this site came from “Diary of Captain John Fassett, Jr,” in The Follett-Dewey Fassett-Safford Ancestry (Columbus, OH: Champlin, 1896),216.

[15]Key sources for the Baker engagement are: Lorimier, At War, 28; Cross, “Narrative,” 285; Allen, History of Vermont, 45; Schuyler to Washington, and Schuyler to the Commissioners for Indian Affairs, August 31, 1775, AA43:467, 493; “A Correspondent has sent us the following Account of a Skirmish happened on Lake Champlain,” Quebec Gazette, August 31, 1775; “Quebec, August 28,” Northampton Mercury, October 23, 1775; Journal of Colonel Guy Johnson, E. B. O’Callaghan, ed., Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New-York, vol. 8 (Albany: Weed, Parsons and Company, 1857), 660.

[16]Allen, History of Vermont, 45.

[17]Lorimier, At War, 28; “A Correspondent …,” Quebec Gazette, August 31, 1775.

[18]Cross, “Narrative,” 285; “A Correspondent …,” Quebec Gazette, August 31, 1775.

[19]“A Correspondent …, Quebec Gazette,” August 31, 1775; Lorimier, At War, 28; Thérèse Benoist to François Baby, Montreal, August 29, 1775, Hospice-Anthelme J.-B. Verreau, ed. Invasion du Canada, Collection de Mémoires Recueillis et Annotes (Montréal: Eusèbe Senecal, 1873), 309; Allen, History of Vermont, 45-46.

[20]Daniel Claus, “Memorandum of the Rebel Invasion of Canada in 1775,” CO 42/36 (microfilm), fol. 38b, Library and Archives Canada; Lorimier, At War, 28; Richard Prescott orders, August 31, 1775, Arthur G. Doughty, ed., “Appendix B – Papers Relating to the Surrender of Fort St. John’s and Fort Chambly,” Report of the Work of the Public Archives for the Years 1914 and 1915 (Ottawa: J. de L Taché, 1916), 6; “Extract of Another Letter from Quebeck, Dated October 1, 1775,” AA4 3:926; “Quebec, August 28,” Northampton Mercury, October 23, 1775.

[21]Examination of Peter Griffin, August 25, 1775, AA4 3:671; Montgomery to Schuyler, August 25, 1775, PSP, NYPL.

[22]Montgomery to Schuyler, August 30, 1775, PSP NYPL; James Livingston to Montgomery, [August 1775], NYPL, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/bad6720b-4792-a00b-e040-e00a18067aa1.

[23]Schuyler to Washington, Schuyler to Jonathan Trumbull, and Schuyler to Commissioners for Indian Affairs, August 31, 1775, AA43:467, 469, 493. Biographer (and descendent) Ray S. Baker contended that Schuyler’s claim that Remember Baker’ went on his fatal mission “without my leave … contrary to the most pointed and express orders,” was a matter of diplomatic convenience — disavowing Baker for the greater good — but the clear language of Schuyler’s orders show that the biographer was working on incorrect assumptions; Ray S. Baker, “Remember Baker,”The New England Quarterly 4, no. 4 (October 1931): 627-28.

[24]Schuyler to Jonathan Trumbull, August 31, 1775, and Schuyler to the Inhabitants of Canada, September 5, 1775, AA43:469, 671-72.

[25]Oliver Wolcott and Volckert P. Douw to Philip Schuyler, September 4, 1775, PSP NYPL; Douw to John Hancock, September 6, 1775 and A Speech to the Chiefs and Warriours of the Six Nations from the Commissioners, August 31, 1775, AA43:494-95; Douw to New York Provincial Congress, October 4, 1775, AA42:1275; Mark R. Anderson, Down the Warpath to the Cedars: Indians’ First Battles in the Revolution(Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2021), 25-27.

[26]Allen, History of Vermont, 46; “Extract of a Letter from a Gentleman at Albany, Sept. 2” and “Extract of a Letter …, Sept. 5, New-York Gazette, September 11, 1775; “Extract of a letter dated at the Carrying Place, near Ticonderoga, September 14, 1775, from an Officer in the New-York Forces,” The Constitutional Gazette (New York), September 27, 1775; “Reflections on Gage’s Letter to General Washington,” The Constitutional Gazette, October 18, 1775.

[27]“Exercises at Isla La Motte Close Celebration,” Bennington Evening Banner, July 10, 1909; “Remember Baker’s Grave,” St. Albans Daily Messenger, September 16, 1905; The Minute Man: Official Bulletin, National Society Sons of American Revolution 24, no. 3 (January 1930): 369; www.vtssar.org/memorials/CPT%20Remember%20Baker.pdf. The Noyan memorial is currently being dismantled and concerned parties are seeking a new home for its bronze plaque.

9 Comments

The engraving at the top of the article shows one of very few depictions of the 10-gun Continental ketch LIBERTY (yes, she was definitely a ketch, not a schooner as many others have said), formerly Sir Philip Skene’s merchant ship KATHARINE captured by Benedict Arnold’s men only a few days after the battles of Concord & Lexington. Although there were neither a Continental Army nor a Continental Navy in being at the time, she was clearly delineated as a Continental vessel, and as such was America’s first national warship. She played important roles in the American capture of Forts Ticonderoga and Crown Point only a few days after she had been commissioned. The engraving fails to show that she had a “pink” or pointed stern, similar to many fishing craft on the Grand Banks.

See our article about the ship:

https://allthingsliberty.com/2019/06/the-liberty-first-american-warship-among-many-firsts/

Contemporaries – from generals to ship captains – consistently described LIBERTY as a schooner. I did not find any primary sources referring to her as a ketch, even though that appears to be the most accurate modern terminology. In period documents, “ketch” appears to have been largely reserved for mortar-armed Bomb-ketches.

I agree with Mark that primary sources all refer to the “Liberty” as a schooner. I have seen one period illustration of the “Liberty”–the lower right frame of “God Bless Our Arms” (https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/wars-and-events/the-american-revolution/north-american-campaigns/lake-champlain-campaign–1776-/battle-of-valcour-island—11-october-1776.html). That looks to be a schooner–both masts are the same height whereas a ketch’s mizzen is shorter and the sail significantly smaller. Also, a ketch’s mizzen is usually mounted closer to the rudder head.

A question: in the engraving heading the article, which craft do you think is the “Liberty?” The one in the distance looks to be a sloop (single mast) and the one about in the center appears to be a brigantine (square-rigged mainmast). The ship to the right is square-rigged on both masts.

While doing some work in the National Maritime Museum website, I took a break and looked for images or drawings of ketches. I thought such rigging featured fore/aft sails but found several ketch images on the NMM site that had square-rigged main masts. Learn something new almost every day.

With that new information, I must say that the ship near the center of the header image with this article could be a ketch. She does, however, seem kinda tall to be the “Liberty” with a hold of only three-and-a-half feet. Plus, it appears to have several gunports hinting at a lower deck. I don’t think the “Liberty” had a lower deck and I doubt it featured any gunports having been built for commercial work.

A fine article, well-written and impeccably researched. That said, Remember Baker was given a “Mission Impossible”. Schuyler’s orders were artfully worded to allow him to disavow responsibility in the event something went wrong. The objective was to look into the ship works 20 miles into Canada and assess the readiness of the vessels being built there. How was he supposed to accomplish that without crossing the border? By going overland through the wilderness. In the aftermath, Schuyler went all-in both throwing Baker under the bus and apologizing to the Caughnawagas. While he dithered in Albany at a council with the Six Nations, Richard Montgomery listened to Peter Griffin’s report and moved with all dispatch to launch the expedition to Canada. In the end, Baker’s ill-fated reconnaissance mission succeeded. Montgomery’s response probably prevented the British from forestalling the expedition and gaining control of Lake Champlain that year.

Baker is probably the one person from that group of individuals in the pre-war New Hampshire Grants who is unknown to most people. Ethan and his brothers and cousins get all sorts of press and Seth Warner makes a name for himself during the war. Hopefully, Mark, your fine article will educate many of those unknowing.

Maybe he would get more press if we called him “Dismember” Baker.

Ouch!

Mark Anderson seems to have an ax to grind with Remember Baker. He treats him as a rogue scout, who disobeyed orders and his folly caused his papers to fall into enemy hands. However, given the following text:

“The four Americans, jarred by Baker’s death, reported seeing just a single Indian paddling off. One of the four survivors may also have been hit by the enemy salvo, since the British later found “a Grass Bed had been made for a wounded Man at some Distance from the dead Man.” The men left Baker where he had fallen, a single shot between his eyes. They did not linger. American participant Uriah Cross simply recounted, “We returned to our boats & shoved off.”” this seems to put responsibility on the remaining four, they were not in an armed conflict from which they had to flee, they abandoned Baker’s body and fled even though they saw just a single indian paddle off. They did not recover the body of Baker or check the body for any items of importance. Perhaps Mr. Anderson is attempting to throw shade on the four, including Uriah Cross. Mr. Andersen never considers that the survivors become the “truth” tellers. Whether true or not. I would put the blame squarely on the scared four who abandoned the body and never checked the body for important items. Drop the ax Mr. Anderson.