The study of intelligence has always suffered from a bias towards the derring-do of spies, stealing of secrets, breaking of codes, and covert action. This is particularly the case with studies of intelligence during the American Revolution.[1] Books and articles on the topic have been premised on an understanding of “intelligence” as effectively limited to spies and secrets. Yet this reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of how the term “intelligence” was used at the time.

When George Washington wrote of “intelligence,” he was referring to a much broader concept, one that encompassed both secret and non-secret sources of information. Nor was he the only one to do so. In their written correspondence, “intelligence” was typically used by rebel leaders as a synonym for “news.” Thus, upon receiving newspapers from his subordinates, Washington would reply with words to the effect, “I am much obliged to you for the intelligence.”[2] As such, the acquisition of intelligence meant acquiring newspapers in addition to the reports of spies in enemy territory, military reconnaissance and similar collection methods.

Newspapers acquired from behind enemy lines, from Britain, and from Europe, were a critical input into the American intelligence system, informal though that system may have been. The important role of newspapers as a source of intelligence has nonetheless been generally ignored. Instead, to the extent newspapers have been of interest to historians, it is the roles they played as instruments of propaganda or as chronicles of the period that have received the bulk of attention.[3]

As commander in chief of the Continental Army, Washington’s intelligence needs were wide-ranging and required a constant flow of information. There is no question that spies operating in British controlled territory provided important intelligence, especially about the enemy order of battle, movements and morale. As the commander of a relatively weak military force, obtaining early warning of a British military buildup and future offensive operations was essential. But being responsible for American strategy meant obtaining intelligence about British policy. After all, how else could Washington judge the effectiveness of his strategy of wearing down the British except in relation to how it was affecting British morale at home, ultimately leading to a shift in British policy? As the rebels gradually acquired European allies, and the war expanded geographically, especially to the Caribbean, the intelligence needs of Washington, the Congress, and America’s diplomats abroad increased as well.

Assessing the impact of any specific type or piece of intelligence on policy and strategy is a difficult endeavor even at the best of times; attempting to do so for the course of a war in the late eighteenth century lasting some seven years is probably impossible. Nevertheless, it is at least possible to demonstrate the importance attached to newspapers as an intelligence source, and to identify the types of information rebel leaders derived from them, some of which were probably unique to that source. It is also important to highlight that a good deal of intelligence obtained by spies operating in enemy territory was derived from newspapers. We know this was the case because many reports from these spies, including from the Culper spy ring, mention newspapers as a source.[4] Therefore, newspapers constituted both a direct and indirect intelligence source. Furthermore, in contrast to the widespread understanding of newspapers as an “open source,” it must be stressed that a clandestine journey was often required to send newspapers from enemy territory to rebel-held territory.

Without doubt, Washington’s correspondence provides the best source demonstrating his reliance on newspapers. Hundreds of Washington’s letters during the war specifically refer to newspapers he had been sent, and often mention he would then pass them on to other rebel leaders.[5] Many of the newspapers Washington read were from British-occupied New York, as well as from Britain itself.

Newspapers not only provided Washington with an important source of political and military information, they also allowed him to cross reference and compare this information from that provided by other sources. Notably, Washington did not treat the news uncritically. After receiving a New York paper announcing the arrival of British naval and army units in the city, he confirmed the naval information through a separate source but was skeptical of the number of soldiers cited due to the “common practice of exaggerating numbers.”[6]

Regardless of their accuracy, newspapers arriving at Washington’s multiple headquarters throughout the war were at a minimum days, but sometimes weeks or months out of date, particularly if they were arriving from Europe. Nevertheless, Washington remained an avid consumer. Newspapers from England, as well as American papers bringing news from England, were eagerly sought. The information they contained not only allowed Washington to assess the state of the British war effort, but also to lobby Congress for more resources. For example, in May 1779, Washington, citing an account of Lord North’s speech to the House of Commons, wrote:

From the general complexion of the intelligence from England and from that of the Minister’s speech of which I have seen some extracts in a New York paper of the first instant, there is in my opinion the greatest reason to believe that a vigorous prosecution of the war is determined on. . . . While England can procure money, she will be able to procure men; and while she can maintain a ballance of naval power she may spare a considerable part of those men to carry on the war here. . . . Under these circumstances prudence exacts that we should make proportionable exertions on our part.[7]

The same newspaper Washington referred to here also contained an announcement of thousands of British troops about to embark for the Americas, though where they would disembark remained secret. Nevertheless, other details proved useful. As Washington observed, “The English papers have frequently announced considerable reinforcements to the army in America and have even specified the particular Corps intended to be sent over.”[8] Based on this information of an escalation of Britain’s war effort, Washington wrote to John Jay, arguing it demanded:

Very vigorous efforts on our part to put the army upon a much more respectable footing than it now is—It does not really appear to me that adequate exertions are making in the several States to complete their Battalions—I hope this may not proceed in part from the expectation of peace having taken too deep root of late in this country.[9]

Likewise, writing separately to Benjamin Harrison, again referring to this report, Washington warned that this large British force on its way to America would produce an “unfavourable turn to that pleasing slumber we have been in for the last eight Months—& which has produc’d nothing but dreams of Peace and Independence.”[10] In effect, Washington was urging a wakeup call.

Washington would return to this theme several years later. In May 1782, Washington wrote to John Hancock:

I have been furnished with sundry New York and an English Paper, containing the last intelligence from England, with the Debates of Parliament upon several Motions made respecting the American War . . . I have perused these Debates with great attention and care, with a View if possible to penetrate their real Design.[11]

In his view, the British Government remained committed to prosecuting the war. The “real Design” Washington referred to here was his belief British “peace feelers” were being used to silence domestic critics of the war in England and to create a “false Idea of Peace, to draw us from our connections with France, and to lull us into a state of security and inactivity.”[12] Though Washington’s analysis was probably wrong in this instance, that he took such interest in British Parliamentary debates reflects his appreciation that these debates were important. Notably it was through the newspapers that he learned of these debates. Washington was not alone in holding these beliefs. Benjamin Franklin, upon reading in the newspaper about a Parliamentary debate on continuation of the war with America, observed that the British people were “sick of it” but “the King is obstinate” and that the rebels should not be lulled into a false belief that anything fundamental in British policy had changed.[13]

Washington obtained various other items of foreign intelligence through the newspapers he was sent. In one instance, he received a Boston newspaper that copied an English paper’s account of the Spanish declaration of war on England, as well as “some other articles of intelligence.”He passed this information to Jay, stating “this may reach Congress sooner than any other notice of it.”[14] Some two months later, Washington sent the President of Congress a New York paper containing accounts showing that “the Inhabitants on the coast of England seemed to be at least as much alarmed as we used to be” due to fear of the combined French and Spanish fleet.[15]

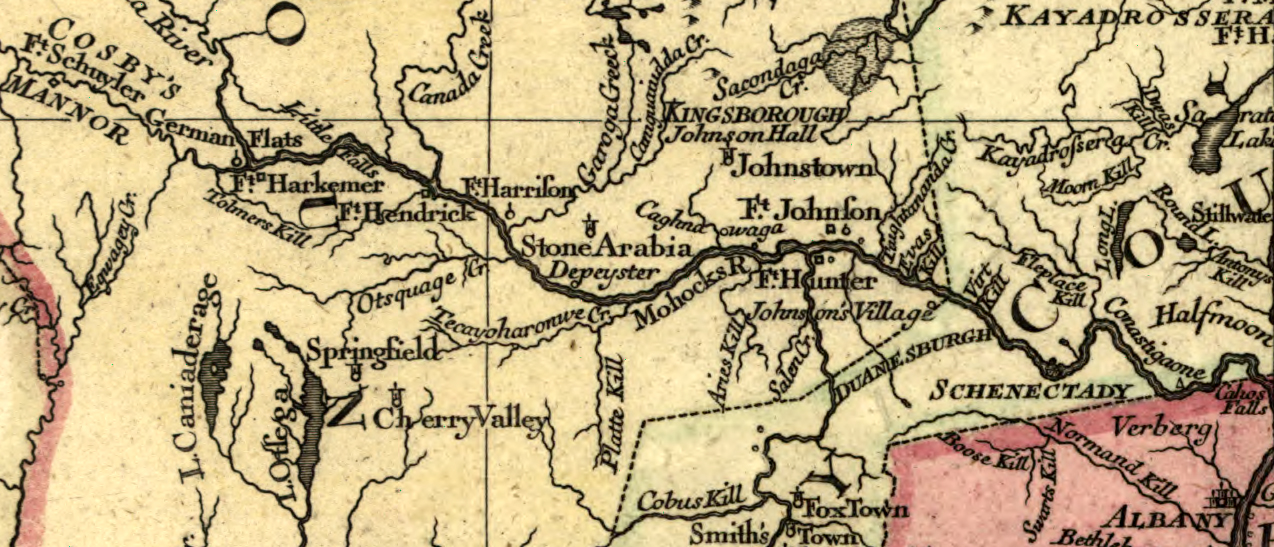

It is telling that many individuals corresponding with Washington would send him newspapers either as a matter of course, or if some item piqued their interest. One of these correspondents, Elias Dayton, upon reading a New York newspaper account of a “rupture between England and the States of Holland” sent it to Washington “by the most expeditious mode of conveyance.”[16] Likewise, Washington was keen to pass on good news to others. Three days after Dayton sent his newspaper to Washington, he in turn wrote to the Comte de Rochambeau, enclosing a New York newspaper “in which you will find a formal declaration of War on the part of Great Britain against the States of Holland.”[17] Rochambeau was keen to receive newspapers and requested that Washington “procure me the New York papers which I can’t get.”[18] Unfortunately, this was a request Washington was unable to fulfill. Highlighting the difficulties of acquiring newspapers from New York, he wrote to Rochambeau: “I wish it were in my power to furnish your Excellency with the New York papers; but as our communication with that place is very irregular, I only obtain them accidentally.”[19] Washington received a good deal of bad news from the newspapers which he also passed on. In late April 1780, he forwarded a New York newspaper to Samuel Huntington detailing the British siege of Charleston. Washington noted, “If these Accounts are true, Our Affairs in that quarter are in a disagreable situation.”[20]

On numerous occasions Washington used the information found in newspapers to track the arrival and departure of British ships and troop transports, as well as to obtain details about the naval war. Washington was provided similar information from other sources, but having newspaper accounts on hand allowed him to cross reference this information as well as to provide details not found in other reports.[21]

An illustration of Washington’s interest in procuring newspapers is reflected in his correspondence with Capt. John Pray, a relatively junior officer in charge of the Water Guard in Nyack, New York. The correspondence began in June 1781 when Pray sent Washington three newspapers from New York. Previously, Pray had “Sent all papers & intiligence to the Commanding Officer at West point . . . but in future shall forward all such to your Excellency.”[22] A year later, Pray was instructed by Washington to organize an intelligence collection mission in New York. As part of this mission, Pray was ordered to collect “domestick or other intelligence contained in the News Papers, which might & should be obtained every day.”[23] In the following months, Pray sent Washington numerous New York newspapers.

Among the ways newspapers were acquired was via an exchange with the British. In one noteworthy case, Alexander Hamilton facilitated an exchange of newspapers for several months beginning in May 1780 with the British Commanding Officer on Staten Island. In exchange for newspapers from New York, Hamilton arranged for the British to receive newspapers from Philadelphia.[24] The exchange gradually broke down as the rebels were unable to regularly deliver the newspapers from Philadelphia. By October, Hamilton noted this “experiment” had failed, blaming the failure in part on Washington’s unwillingness to pursue it fearing “popular jealousies.”[25]

The rebels’ agents and diplomats stationed abroad were also keen consumers and suppliers of newspapers. When the Committee of Secret Correspondence provided instructions to its Europe-based agent C. W. F. Dumas, these included sending back to America “regular supplies of the English and other newspapers.”[26] Five years later, when responsibility for Dumas’ activities was transferred to the office of Foreign Affairs, Robert Livingston, as its new head, instructed him to subscribe to the “Leyden and Amsterdam Gazettes” and send these to America.[27]

Similarly, in late 1776, the Committee of Secret Correspondence instructed Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane and Arthur Lee in their role as Commissioners to France, to “send to us in regular succession some of the best London, French, and Dutch newspapers.”[28] Whilst based in France, Franklin requested a regular supply of the London Evening Post and the London Chronicle.[29] Acquiring news from England not only provided insights into British policy, but also allowed Franklin to follow developments in America. As he would write to the Marquis de Lafayette: “American News there is none,—but what we see in the English Papers.”[30] In addition to receiving newspapers from America, Franklin sent European newspapers back to Congress. In one correspondence with Livingston, he thanked him “for the News Papers you have been so kind as to send me” and added, “I send also to you by every Opportunity, Pacquets of the French, Dutch, and English Papers.”[31]

John Adams also placed great importance on acquiring newspapers. Writing to the President of Congress, he stated, “I have the Honour to inclose to Congress, the latest Gazettes. We have no other Intelligence than is contained in them.”[32]Adams’ main source of supply for English newspapers was Thomas Digges, an American living in England. Digges regularly sent Adams copies of the London Courant, the London Evening Post, and the London Packet.[33] Similar to Washington and Franklin, Adams followed the British Parliamentary debates recorded in the newspapers to gauge the British mood for continuing the war.[34] Adams also forwarded European newspapers to Congress. In one of his messages, he wrote: “I have the Honor to inclose the English Papers” as well as “The Courier de L’Europe and the Hague, Leiden and Amsterdam Gazettes.”[35] In a separate message, Adams was quite clear about his intent to send newspapers back to the Congress, and noted their value:

I have . . . packed up all the newspapers and pamphlets I can obtain. . . . These papers and pamphlets, together with one or two English papers, for which I shall subscribe as soon as possible, I shall do myself the honor to transmit to Congress constantly as they come out. From these, Congress will be able to collect from time to time all the public news of Europe.[36]

Adams recognized the value of procuring as many newspapers as possible to ensure the entire spectrum of British political debate was represented. As he explained:

the General Advertiser, and the Morning Post, both of which I shall for the future be able to transmit regularly every week. Congress will see that these papers are of opposite parties, one being manifestly devoted to the Court and the Ministry, and the majority, the other to the opposition, the committees, the associations, and petitions; between both I hope Congress will be informed of the true facts.[37]

An appreciation of the rebel dependence on newspapers as a source of intelligence also puts a different complexion on the historical controversies about whether Thomas Digges[38] was a British spy and James Rivington[39] a rebel spy. In the case of Digges, his diligent supply of English newspapers to Adams, a key source of intelligence, must be accounted for in any assessment of his guilt or innocence. As for Rivington, although his Loyalist New York newspaper, The Royal Gazette, published pro-British and anti-rebel propaganda, it was still regarded by Washington as a key source judging by the rebel efforts to obtain copies of this publication as well as the frequency Washington referred to it in his correspondence. Had Rivington also secretly been providing intelligence to the rebels, it is essential to weigh the value of any clandestine reports relative to the information he openly conveyed in his newspaper.

Without wishing to downplay the importance of secret intelligence, it is necessary that the holistic definition of “intelligence,” as understood at the time includes non-secret sources. Newspapers were a major source of rebel intelligence. The evidence presented here is merely a first step in the direction of recognizing and analyzing this fact. Once its value is more widely appreciated, future studies will hopefully stress the importance of open sources and begin to recast our understanding of intelligence during the war.

[1]The titles of key works on intelligence during the war are indicative of this bias, not to mention the contents of these works that barely touch upon the importance of newspapers as a source of intelligence, assuming newspapers receive any mention at all. Some examples include: John Bakeless, Turncoats, Traitors and Heroes: Espionage in the American Revolution (New York: J.B. Lippencott and Co., 1959); Alexander Rose, Washington’s Spies: The Story of American’s First Spy Ring (New York: Bantam, 2006); Sean Halverson, “Dangerous Patriots: Washington’s Hidden Army During the American Revolution,” Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 25, No. 2 (2010), 123–146; Kenneth A. Daigler, Spies, Patriots, and Traitors: American Intelligence in the Revolutionary War (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2014); John A. Nagy, “George Washington Spymaster” in Edward G. Lengel, ed., A Companion to George Washington (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2012), 344–357.

[2]George Washington to John Neilson, May 31, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0655.

[3]Todd Andrlik, Reporting the Revolutionary War: Before It Was History, It Was News (Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2012).

[4]See for instance: Enclosure: Samuel Culper Jr. to Benjamin Tallmadge, January 22, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-19-02-0092-0002; Enclosure: Culper Jr. to Tallmadge, July 15, 1779: founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0576-0004; Washington to Tallmadge, February 5, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-19-02-0133.

[5]References to newspapers Washington has read appear in correspondence with, amongst others: Lt. Col. Loammi Baldwin, Maj. John Clark Jr., Vice Adm. D’Estaing, Maj. Gen. John Sullivan, Brig. Gen. Samuel Holden Parsons, Brig. Gen. Charles Scott, Maj. Gen. Stirling, Brig. Gen. William Maxwell, Henry Laurens, John Jay, Maj. Benjamin Tallmadge, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, Lt. Col. Benjamin Ford, Brig. Gen. John Neilson, Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne, Gouverneur Morris, William Livingston, Benjamin Harrison, Samuel Huntington, Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, Elias Dayton, Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton, William Heath, John Amboy, John Pray, John Hancock, and Jonathan Dayton.

[6]Washington to Vice Adm. d’Estaing, September 20, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-17-02-0057.

[7]Washington to William Livingston, May 4, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0287.

[8]Washington to John Jay, May 5, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0301.

[10]Washington to Benjamin Harrison, May 5–7, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0299.

[11]From George Washington to John Hancock, May 4, 1782, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-08321.

[13]From Benjamin Franklin to Robert R. Livingston, March 4, 1782, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-36-02-0471. See also, Benjamin Franklin to Robert Morris, March 9, 1782, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-36-02-0494.

[14]Washington to Jay, August 29, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0229.

[15]Washington to Gouverneur Morris, November 6, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-23-02-0171.

[16]Elias Dayton to Washington from Elias Dayton, March 18, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-05131.

[17]Washington to comte de Rochambeau, March 21, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-05150.

[18]Rochambeau to Washington, November 27, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-04085.

[19]Washington to Rochambeau, December 10, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-04190.

[20]Washington to Samuel Huntington, April 28, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-25-02-0359.

[21]Some examples can be found in the following correspondence: William Heath to Washington, September 30, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-07057; Washington to Huntington, November 4, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-03811; Washington to Huntington, 15 December 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-04234.

[22]John Pray to Washington from John Pray, June 27, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-06190.

[23]David Cobb to Pray, August 14, 1782, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-09134.

[24]From Alexander Hamilton to Marquis de Barbé-Marbois, May 6, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0664; Alexander Hamilton to Marquis de Barbé-Marbois, May 18, 1780: founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0677; Hamilton Barbé-Marbois, May 31, 1780,founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0691; Hamilton Barbé-Marbois, July 20, 1780,founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0771.

[25]Hamilton to Barbé-Marbois, October 12, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0898.

[26]Committee of Secret Correspondence to C.W.F. Dumas, October 24, 1776. Jared Sparks (ed) The Diplomatic Correspondence of the American Revolution, Vol. IX (Boston: 1830).

[27]Robert R. Livingston to Dumas, November 28, 1781. The Diplomatic Correspondence of the American Revolution, Vol. IX.

[28]Committee of Secret Correspondence to Franklin, Silas Deane, and Arthur Lee, December 21, 1776. The Diplomatic Correspondence of the American Revolution, Vol. I (Boston: 1829).

[29]Franklin to Monsoir Genet, June 29, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-26-02-0631.

[30]Franklin to Lafayette, November 10, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-31-02-0042.

[31]Franklin to Livingston, March 4, 1782,founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-36-02-0471.

[32]From John Adams to the President of the Congress, September 11, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-07-02-0021.

[33]Enclosure: A List of Pamphlets and Newspapers, April 25–June 10, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-09-02-0251-0002.

[34]Adams to the President of the Congress, No. 10, February 27, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-08-02-0246; Adams to the President of Congress, 23 March 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-09-02-0054.

[35]Adams to the President of Congress, March 23, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-09-02-0054.

[36]Adams to the President of Congress, February 23, 1780, The Diplomatic Correspondence of the American Revolution, Vol. IV (Boston: 1829).

[37]John Adams to the President of Congress, March 20, 1780, ibid.

[38]William Bell Clark, “In Defense of Thomas Digges,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 77, No. 4 (1953), 381-438.

[39]Catherine Snell Crary, “The Tory and the Spy: The Double Life of James Rivington,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 16, No. 1 (1959), 61-72; Todd Andrlik, “James Rivington: King’s Printer and Patriot Spy,” Journal of the American Revolution, March 3, 2014, allthingsliberty.com/2014/03/james-rivington-kings-printer-patriot-spy/.

2 Comments

Newspapers were indeed a source of “intelligence” particularly within the Georgian culture of the war. They often provided tactical military information. However, your introductory sentence is a bit of an extreme.

Excellent article, thank you! — and an important distinction that “intelligence” then meant simply “information.”

I, too, have come across many instances of patriots forwarding loyalist newspapers. Capt. Jabez Fitch of Greenwich, CT, who frequently served as a spy, often forwarded New York papers to Gov. Jonathan Trumbull.

I was particularly interested to read a September, 1781 letter from Dr. James Cogswell of Stamford to his father in western Connecticut, in which he said that he had access to the NYC papers because “Col. Upham who commands on Lloyds Neck sends them to me every Flag.” At this time, the Associated Loyalists under Joshua Upham had been attacking the Connecticut coast non-stop for seven months. I have been curious why an enemy officer would send newspapers to a rebel doctor. Gratitude for medical care to prisoners? Spreading propaganda? Recycling, once the papers were out of date? Simple kindness? I have no idea.

Thanks again for a good read.