This article was originally published in Journal of the American Revolution, Vol. 1 (Ertel Publishing, 2013).

Solving “the Most Astounding” Mystery of the American Revolution

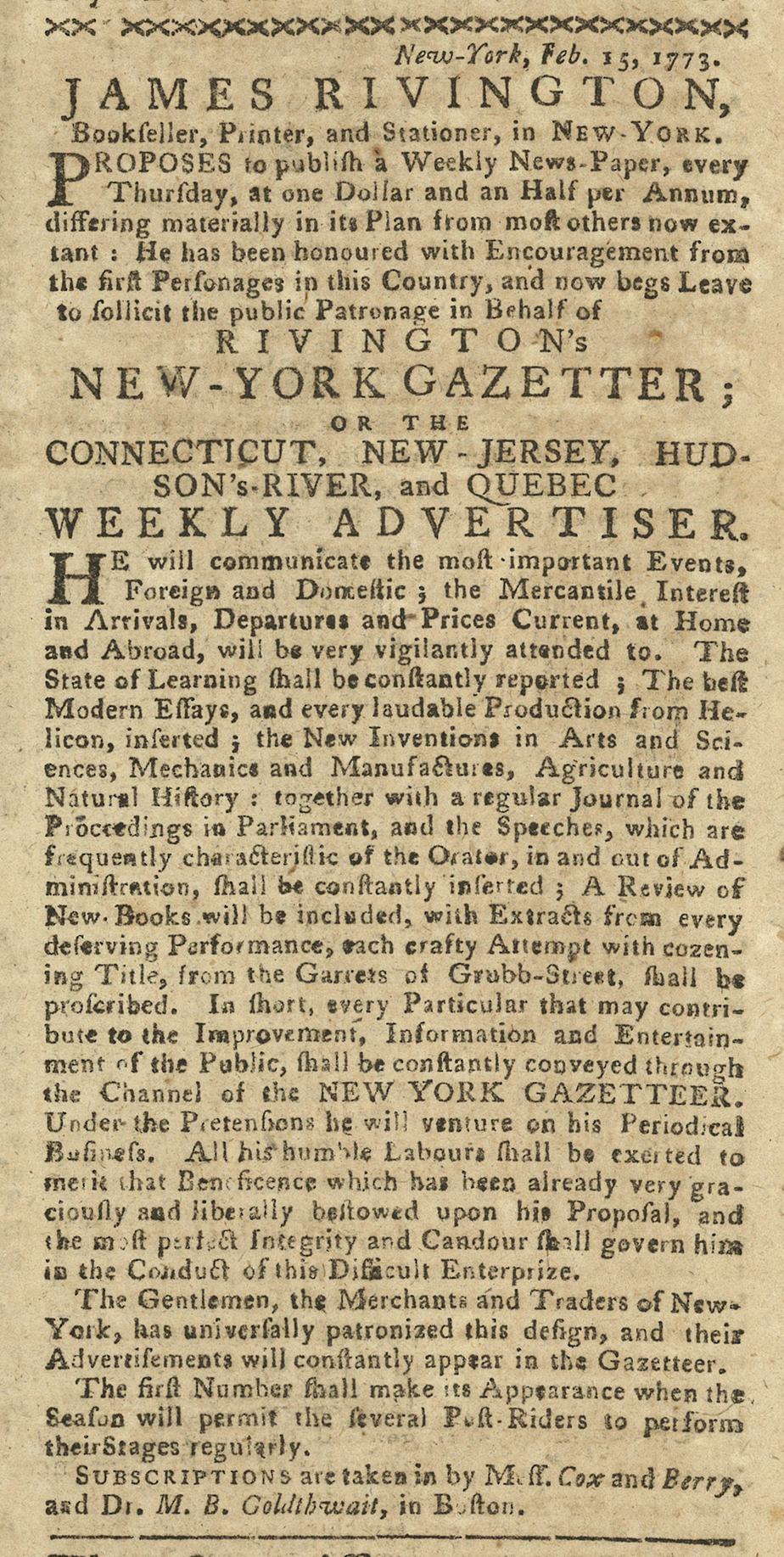

In early spring 1773, readers of the Boston Gazette came across an ambitious business proposal when they opened the March 22 issue. New York printer and bookseller James Rivington, then about fifty years old, planned to publish a weekly newspaper every Thursday for inhabitants of the middle and New England colonies to “communicate the most-important Events, Foreign and Domestic; the Mercantile Interest in Arrivals, Departures and Prices Current, at Home and Abroad.” Rivington claimed that the newspaper would feature “every Particular that may contribute to the Improvement, Information and Entertainment of the Public.”[i]

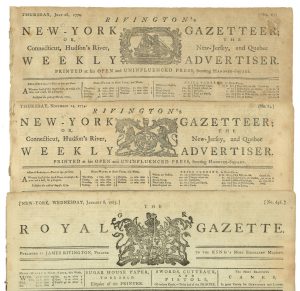

Rivington had arrived in America from London in 1760 and eventually found himself in New York, where he opened a bookstore in Hanover Square. His first issue of Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer published on April 22, 1773. Despite claims to be an “open and uninfluenced press,” as stated on the 1774 masthead of his newspaper, Rivington was soon perceived as leaning Loyalist. In November 1774, the Gazetteer’s nameplate switched from featuring a decorative woodcut of a ship to the Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom.

Every week, Rivington served as the mouthpiece for anti-Whig accusations and barbs aimed at Patriots in New York and beyond. Rivington’s extensive geographic reach and growing circulation, which he boasted was 3600 in October 1774, made him an easy target for Patriots far and wide.[ii]

“The swelling popular wrath generated an unprecedented intercolonial campaign to force Rivington out of business,” wrote Arthur M. Schlesinger in his 1958 book Prelude to Independence: The Newspaper War on Britain 1765-1776. “In the weeks following the First Continental Congress cancellations of subscriptions poured in from as far south as South Carolina.”[iii]

For example, the Committee of Observation for Elizabethtown, New Jersey, unanimously resolved in December 1774 “that they will take no more of said Rivington’s Gazettes, nor send any advertisements to be inserted therein, or have any further dealings or commerce with him.”[iv]

Benjamin Edes and John Gill, who two years prior published Rivington’s newspaper launch advertisement in their Boston Gazette, now called his work “dirty, malicious paragraphs and… greatly misrepresenting.” In return, Rivington called Edes and Gill printers of a weekly “Dung Barge.”[v]

Boycotts and insults soon escalated into protests, intimidation and property destruction. On April 13, 1775, Rivington learned that he had been hung in effigy by a mob in New Jersey. One week later, and three days before New Yorkers received word of the bloodshed in Massachusetts, Rivington published his counterattack on the New Jersey mob. In what could be perceived as the eighteenth-century equivalent of a public service announcement, a woodcut depicting his effigy accompanies Rivington’s passionate plea for freedom of the press:

The Printer is bold to affirm, that his press has been open to publications from ALL PARTIES; and he defies his enemies to produce an instance to the contrary. He has considered his press in the light of a public office, to which every man has a right to have recourse. But the moment he ventured to publish sentiments which were opposed to the dangerous views and designs of certain demagogues, he found himself held up as an enemy to this country, and the most unwearied pains taken to ruin him. In the country wherein he was born he always heard the LIBERTY OF THE PRESS represented as the great security of freedom, and in that sentiment he has been educated; nor has he reason to think differently now on account of his experience in this country. While his enemies make liberty the prostituted pretence of their illiberal persecution of him, their aim is to establish a most cruel tyranny, and the Printer thinks that some very recent transactions will convince the good people of this city of the difference between being governed by a few factious individuals, and the GOOD OLD LAWS AND CONSTITUTION, under which we have so long been a happy people.[vi]

In May 1775, a mob of Sons of Liberty attacked Rivington’s home and printing office, destroying his press and forcing him to flee to a British naval ship in the harbor. “From this ark of refuge he then ‘humbly’ petitioned the Second Continental Congress for pardon, assuring it that ‘however wrong and mistaken he may have been in his opinions, he has always meant honestly and openly to do his duty,’” Schlesinger wrote. The Continental Congress referred the petition to the New York Provincial Congress, which pardoned Rivington and permitted him to resume publication. In November 1775, a large mob struck Rivington’s printing shop again, and he soon sailed for England, only to return to British-occupied New York in 1777 with a new press and an appointment to the £100-per year role as the king’s printer. The re-launched newspaper maintained its serial numbering, continuing with No. 137 on October 4, but assumed the new name of Rivington’s New-York Gazette for two issues before becoming Rivington’s New York Loyal Gazette. On December 13, 1777, the newspaper changed its name another time to the Royal Gazette, which it kept until issue No. 746 on November 19, 1783. The newspaper finally removed “Royal” from its title and survived 12 more issues under the name Rivington’s New-York Gazette.

In mid-December 1783, the Massachusetts Gazette (Springfield, MA) printed the complete text of the peace treaty and details of Washington’s farewell to his officers at Fraunces Tavern in New York. On the same page as the farewell, under a “Springfield, Dec. 16” dateline, was the following:

It is reported as an undoubted fact, that Mr. JAMES RIVINGTON, Printer at New-York, was, as soon as our troops entered the city, protected in person and property, by a guard, and that he will be allowed to reside in the country, for reasons best known to the great men at helm.[vii]

This surprising bit of news presumably had inhabitants of Massachusetts speculating about Rivington’s potential role as a double agent, supporting Washington’s New York spy network, known as the Culper Ring. The single paragraph was reprinted by several nearby newspapers, including the December 25 issues of the Massachusetts Spy (Worcester, MA), Continental Journal (Boston) and Salem Gazette (Salem, MA). Edes and Gill inserted the text in their December 29 edition of the Boston Gazette with a three-word postscript: “Where is Arnold!”

Rivington’s newspaper officially ceased publishing on December 31, 1783, when prominent Sons of Liberty John Lamb, Marinus Willett, and Isaac Sears forced Rivington to shut down his business. Rivington obeyed, apparently without the fervent freedom-of-the-press fight he put up eight and a half years earlier.[viii]

On January 4, 1784, North Carolina lawyer William Hooper shared some gossip with North Carolina judge James Iredell that “It has come out, as there is now no longer any reason to conceal it, that Rivington has been very useful to Gen. Washington by furnishing him with intelligence. The unusual confidence which the British place in him, owning in a great measure to his liberal abuse of the Americans, gave him ample opportunities to obtain information, which he has bountifully communicated to our friends.”[ix] The letter, published in the 1850s, shows that the story of Rivington’s true loyalty circulated in and beyond New York soon after the end of the war, but with little detail.

Ashbel Green, a clergyman who served as chaplain to the U.S. Congress (1792 to 1800) and president of Princeton University (1812-1822), piled on the rumors with more juicy details in an 1840 letter to “My Dear A.”

At the commencement of our Revolution, and indeed through the whole of its progress, the patriots of the day made great use of the press, in operating on the public mind. The tories attempted the same, as long as they were permitted to do it, which was till about the time of the declaration of our independence. After that, they could circulate nothing, except what was printed within the British lines, and sent forth and handed about privately…

Rivington remained in the city of New York after it was abandoned by the American troops, and became king’s printer during the whole of the ensuing war, and nothing could exceed the violence of his abuse of the rebels, as he delighted to call the Americans, and the contempt with which he affected to treat their army, and Mr. Washington, its leader. It was, therefore, a matter of universal surprise, on the return of peace, that this most obnoxious man remained after the departure of the British troops. But the surprise soon ceased, by its becoming publicly known, that he had been a spy for General Washington, while employed in abusing him, and had imparted useful information, which could not otherwise have been obtained. He had, in foresight of the evacuation of New York by the British army, supplied himself from London with a large assortment of what are called the British classics, and other works of merit; so that, for some time after the conclusion of the war, he had the sale of these publications almost wholly to himself.[x]

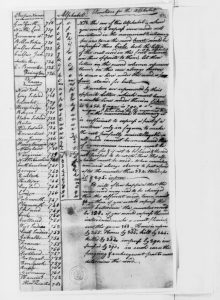

Another document that offers intrigue about Rivington’s possible work for the Americans is the secret code book of Benjamin Tallmadge, Washington’s head spymaster and organizer of the Culper Ring. In late July 1779, Tallmadge created the document, which contained a list of 763 numbers assigned to names and words, and served as a key for encoding and decoding sensitive communication. For instance, General Washington was 711; Tallmadge (operating as John Bolton) was 721; Abraham Woodhall (Samuel Culper, Sr.), 722; Robert Townsend (Culper, Jr.), 723; Lord North, 719; Lord Germain, 720; and Rivington, 726.[xi]

“Rivington did not have both a codename and a codenumber in the Tallmadge code,” wrote Ralph E. Webster in 2010 in his United States Diplomatic Codes and Ciphers: 1775-1938. “Therefore he did not have double protection as did Tallmadge, Townsend, and Woodhull; this evidence suggests he had not become a double agent before July 1779, when Tallmadge prepared the code.”[xii]

While there is testimony and circumstantial evidence suggesting Rivington was an American spy, there is also indirect support to the contrary, including a letter from Townsend to Washington on July 15, 1779, that shares his fears about Rivington discovering the Culper Ring.[xiii] Townsend’s worries stem from a newspaper item Rivington published five days earlier in the Royal Gazette under the dateline “New-York, July 10”:

Still the rebels cherish one another with assurances, of eating their next Christmas dinner in New-York… Indeed Mr. Washington has declared he will very soon visit that Capital with his army, as it is confessed, without the least reserve, there are many Sons of liberty in New-York, that hold a constant intercourse and correspondence with the Commander in Chief of the Rebel army, from whom he is supplied with accurate communications of all arrivals and departures, and of every thing daily carrying on there, both in the military and civil branches.[xiv]

And what about Rivington’s name in Tallmadge’s code book as 726? Some may argue that it proves nothing because there are other British non-agents assigned to a number and appearing in the same column like Lord North and Germain. While others may focus on the seemingly intentional structure of the list, which appears to place all intelligence subjects – British General Thomas Garth, North and Germain – together at the top of the list with intelligence operatives – Tallmadge, Townsend, Austin Roe, Caleb Brewster and Rivington – bundled at the bottom. Though no secret correspondence has turned up with hard evidence of 726’s activity, accumulating circumstantial evidence makes Rivington someone worth studying. In fact, several historians from the 19th century on have tackled the Rivington story with the assumption that he was a spy and instead focused on two other mysteries: When did Rivington start working for the Americans and why?

In 1860, the memoirs of George Washington Parke Custis, Martha Washington’s grandson were published posthumously, edited by Benson J. Lossing. “Of all the mysteries that occurred in the American Revolution, the employment of Rivington, editor of the Royal Gazette, in the secret service of the American commander is the most astounding,” wrote Custis.

Custis’s memoirs revealed that Rivington, the famous printer of Loyalist sentiments and target of the Sons of Liberty, was one of General Washington’s top spies in 1781 and suggested his espionage began as early as the winter of 1776-1777.[xv]

“Rivington’s method of conveying intelligence to Washington was ingenious,” wrote Lossing in the footnotes of Custis’s memoirs. “He published books of various kinds, and by means of these he carried on his treasonable correspondence. He wrote his secret billets upon thin paper, and bound them in the cover of a book, which he always managed to sell to those spies of Washington, who were constantly visiting New York, and who, he knew, would carry the volumes directly to the headquarters of the army. The men employed in this special service were ignorant of the peculiar nature of it.”

According to Custis, Washington’s trip to New York in 1783 wasn’t only to bid an emotional farewell to his officers at Fraunces Tavern. “When Washington entered New York a conqueror, on the evacuation by the British forces, he said one morning to two of his officers: ‘Suppose, gentlemen, we walk down to Rivington’s bookstore; he is said to be a very pleasant kind of fellow.’”

Rivington, who surprised many by remaining in New York after the evacuation, supposedly welcomed his visitors with open arms. In a private room behind a partially opened door, Washington placed two heavy purses of gold on a table, which one of the officers apparently heard from just outside the room, according to Custis, who said he learned the story from General “Light Horse Henry” Lee, who had it from one of the officers accompanying Washington on the Rivington visit. Editor Lossing corroborated the details of Custis’s story from a second source, Senator John Hunter of Hunter’s Island, Westchester County, who purportedly got it from Rear Admiral Thomas White, midshipman under Rear Admiral Thomas Graves.

A British naval officer having inside information about a spy for the Americans suggests a lot of people heard about Rivington’s espionage after the war, but few – if any – had solid information, particularly about when and why. Looking at the chain of sources, officer to Lee to Custis and White to Hunter to Lossing are wicked games of telephone that would be considered a stretch to believe had Custis and Lossing been impeccable historians, but they’re not.

According to Edward G. Lengel, editor of The Papers of George Washington, Custis told a lot of stories about his step-grandfather. In Inventing George Washington, Lengel calls Custis “a ne’er-do-well and habitual liar” who squeezed money from the fame of his celebrated relative by writing and selling popular history books. Custis wrote “short essays and anecdotes about Washington that appeared in serial form over thirty years and were published in 1859, two years after his death, as the Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington. Custis’s tales were an odd mixture of truth, exaggerations, and outright lies.”[xvi] Custis’s story about Washington dropping off two bags of gold with Rivington is a case in point and highly suspect. Lossing, editor of Custis’s memoirs, is also known as a print-the-legend guy and therefore another easily disputable source among historians. Sure, there may be an ounce of truth somewhere in Custis’s version, but more helpful clues about Rivington surfaced in the mid twentieth century.

In January 1959, about a century after Custis’s memoirs were printed in book form, William and Mary Quarterly published Catherine Snell Crary’s” The Tory and the Spy: The Double Life of James Rivington,” which clearly outlined arguments for and against the Rivington spy story.[xvii]

Crary pointed out that historians were not convinced because Custis’s source was not firsthand. She also took issue with the words of those who closely studied Rivington. “If biographers of Rivington repeated the story at all,” Crary explained, “they cautiously hedged with such words as ‘it is said,’ or ‘as alleged.’ Most writers on colonial printers or Revolutionary espionage ignored it completely.”

While Crary provided some arguments against Rivington’s role as a double agent, the case she presented in favor seemed overwhelming.

First, Rivington had opportunity. Not only was he serving as traffic control for British news and information via his New York newspaper, but he also opened a coffee house, a frequent hang-out for high-ranking British officers. What to do with all that information? More so, the coffee shop was financed in part by merchant and, wait for it, American spy Robert Townsend, also known as “Culper Junior.”[xviii]

Second, he had motive. Rivington had financial difficulties stemming from a declining printing business, growing overhead costs and no salary income as king’s printer after 1779.[xix]

Third, there was “new evidence” in the form of a firsthand account by Allen McLane, considered one of Washington’s most effective informants, who points to Rivington as a key reason for success at Yorktown. McLane explained in his memoirs that he obtained the Royal Navy’s signal book from Rivington, which he delivered to Admiral Francois Joseph Paul Comte de Grasse, commander of the French Fleet, to help during the Siege of Yorktown. The apparent smoking gun came in the form of a letter written in McLane’s own hand:

After I returned in the fall [August 26, 1781, from the West Indies, I] was imployed by the board of war to repair to Long Island to watch the motion of the British fleet and if possible obtain their Signals which I did threw the assistance of the noteed Rivington. Joined the fleet Under the Count D Grass with the Signals.[xx]

On September 5, 1781, the largest naval battle of the Revolutionary War took place off the Virginia coast stacking de Grasse’s twenty-four ships of the line against Rear Admiral Thomas Graves’s nineteen. The Battle of the Virginia Capes resulted in a decisive French victory and de Grasse maintained a strategic blockade at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay and the York River, providing Washington with a naval advantage over Cornwallis. Whether the intelligence about the British Navy’s signals arrived in time for the September 5 battle or not, Judge Richard Peters, who directed the Board of War in 1781, wrote to McLane that de Grasse had been highly gratified with the information.[xxi] As director of the Board of War, Peters provided General Washington with an account of the transaction:

By a Channell of Intelligence I have opened I can procure Access to Rivington’s Printing Office where there is a Person ready to furnish any important Papers as Intelligence! But the Person to bring it is the one I have employed & he in N. York will trust no other. I mention this to your Excellency that if you can think of any material Use to be made of this you will please to take Advantage of it thro’ me as it is confined to my Knowledge only which is the Reason of my personal Address to you. I some Time ago procured a Copy of the British Signals for their Fleet & gave them to the Minister of France to transmit to Compte de Grasse. I had again sent in the Person employed on the former occasion & he has brought out some addition[al] Signals & among them those for the Troops now embarked on Boa[rd] the Fleet on their present Enterprize to the Chesapeak to proceed in which they had fallen down to the Hook yesterday Morning with Sr H. Clinton’s Baggage on Board. My Informant makes their Number of the Line to be 28… I have thought the Knowledge of these Signals to be so important that I have prevailed on Capt. McLean to carry them to Compte de Grasse with a Letter from the Minister to the Compte in which he is requested to transmit them if necessary by Capt. McLean to your Excellency. The Signals have been reprinted with no Alterations but the Change of the Name of Arbuthnot for Graves. The written Part was copied from the original given to be reprinted.[xxii]

Although Peters’s letter came right out and said there was a mole in “Rivington’s Printing Office,” it begs the question: Was Rivington the mole or one of his employees? If it was Rivington, why didn’t he just say Rivington, especially after McLane wrote he obtained the signals “threw the assistance of the noteed Rivington.” Putting the two together, did McLane use sarcasm in the phrase “assistance of the [noted] Rivington” as in he acquired the signals from under Rivington’s nose with the help of a staffer.

Washington responded to Peters: “I do myself the pleasure to acknowledge your Favor of the 19th inst. pr Capt. McClain, and thank you for the intelligence you have communicated; The particular mode you have adopted to obtain information, I think may be very usefully employed, and is a fortunate expedient; the necessity of its use to our present operations is happily at an end, if continued, it may be of importance to some future designs.” Outside the letter is: “Genl. Washington, Secret Service, Capt. McLane.”[xxiii]

If Rivington was in fact the mole, not one of his employees, Washington may have just solved the “when” mystery. Does “if continued, it may be of importance to some future designs” imply that was the first time Rivington acted on America’s behalf? If so, that could put the moment Rivington switched in late August-September 1781 and add extra significance to the McLane papers, which might be the most convincing evidence yet.

Adding fuel to the fire, Crary identified a second document (by an unknown author) in the McLane papers suggesting Rivington was McLane’s New York contact. Housed at the New York Historical Society, the manuscript reads, “On her [the ship’s] return he [McLane] was stationed by the Board of War near Sandyhook to correspond with R of New York received the Signals for the British fleet out of New York delivered them to Count De Grass acted occasionally on the Shore and with the French fleet after Cornwallis had surrendered.”[xxiv]

“The newly discovered McLane document leaves no doubt as to Rivington’s duplicity,” wrote Crary. “What remains a mystery is whether his part in American espionage was limited to 1781 [Crary didn’t pick up on the timing clue provided within Washington’s thank you letter to Peters]. In that connection, the association with Robert Townshend in running a coffee house for British officers needs further investigation. It is unlikely Rivington changed sides before 1779, as Custis thought, for Rivington wrote to Richard Cumberland, Secretary to the Board of Trade, on November 23, 1778, in terms which were unmistakably loyalist.”[xxv] Almost 15 years after her article in William and Mary Quarterly published, Crary speculated that Rivington’s “switch of allegiance to the rebel side probably [occurred] some time in late 1779 or 1780.”[xxvi]

Another breakthrough in the mystery came in 1986 when historian Philip Ranlet, in his book The New York Loyalists, suggested that a significant piece of evidence points to 1778 as Rivington’s year of entry to the American spy network. On October 24, 1778, Gouverneur Morris, New York delegate to the Continental Congress, informed congress that he had “received application from a person in the city of New York, to know whether, in the opinion of the delegates of that State, he may, with safety to his person and property, continue in that city upon the evacuation thereof by the British troops.”[xxvii] The same argument resurfaced in 2006 when the Binghamton Journal of History published Kara Pierce’s “A Revolutionary Masquerade: The Chronicles of James Rivington.” Pierce, who relied heavily on questionable sources like Custis and Lossing, also stressed Ranlet’s theory about Morris’s letter, adding that “Morris also told the congress that this man could provide useful intelligence and to grant his request.”[xxviii]

Morris’s letter turns out to be more bummer than breakthrough considering “a person in the city of New York” could be anyone. And while Pierce left many theories unchallenged, concluding that Rivington was indeed “a Tory and a spy,” she did debate several of Crary’s timing arguments:

- “Crary’s analysis of Rivington’s life and the date of his changing allegiance is too late to be accurate without significant documentation, which she does not provide.”

- “She insists that Rivington was still Loyal to the British crown in 1778 because of a letter written to Richard Cumberland that contains clear loyalist sentiments. However, she refutes her own argument in a later section of her essay. She says, ‘Whatever the time of Rivington’s about face, he played his Tory part to the end.’ This statement clearly refutes her Cumberland evidence—who is to say that this letter was not simply a cover up?”

- “Crary also tries to corroborate this date with the use of the recollections of Allen McLane who discusses an account of Rivington’s duality. However, she does not provide any evidence that proves this is the first occasion in which he spied for Washington. It is likely that Crary’s date represents the time when people began to suspect that Rivington was a spy.”

- “Whereas Crary’s date is too late to be accurate, Custis’s date is far too early to be accurate. His proposition that Rivington became a Patriot spy in 1776 is absurd. Rivington could not have possibly become a Patriot spy at this time because he was not even in the country. By January of 1776, Rivington was already on his way back to England and did not return to New York until 1777. There is no evidence documenting anyone communicating with Rivington in England from the colonies, so this type of arrangement could not have been made at this time.”

So where does all this leave us for guessing when Rivington first flipped, if at all? Custis: As early as late 1776. Crary: Late 1779 or 1780. Ranlet/Pierce: Late 1778.

A definitive “when” answer seems impossible, but one might like to hypothesize that Rivington was considering the change as early as mid-1778, continuing to fling printed Patriot insults as a distraction while proactively applying to Morris that October for safety in exchange for his intelligence (maybe that is the safety granted to Rivington after the war). However, allowing for communication, consideration and a number of other time-delaying factors, one could easily put Rivington’s official turn date in mid-1779, which is precisely the time when Washington pressed his spy network for more information on British plans during the struggle for the Hudson River and when Tallmadge labeled Rivington as codenumber 726. Then again, it’s hard to ignore the McLane letter and subsequent Washington letter to Judge Peters, which potentially provide the most precise reversal date of late August-September 1781.

All of this, of course, is pure conjecture. If we accept the undated McLane letter as the smoking gun proof of Rivington’s Patriot support, then the actual moment when he flipped and why remain two of the Revolution’s best kept secrets. Despite the data, and ignoring the historians who have already assumed Rivington’s spy activity only to focus on when and why, many scholars still demand more concrete evidence before jumping on the secret agent bandwagon. For example, added context to the McLane papers and a handwriting analysis of the letter by an unknown author would be nice.

If I ever get the time, I would like to closely examine each of the 185-or-so Royal Gazette issues printed between December 13, 1777, and October 31, 1779, and the 40-or-so issues from July through October 1781, to explore any subtle differences or detectable changes in Rivington’s reporting that might provide hints. One obvious modification that may or may not provide a clue is when Rivington doubled the frequency of his newspaper the week of May 11, 1778. Previously, Rivington’s Gazette had always been a weekly, but on Wednesday, May 13 he switched to a twice-weekly routine that he sustained with only a couple exceptions until the end of the war.

Rivington printed his last issue of the Royal Gazette on December 31, 1783. By the late 1790s he was deep in debt and died in New York in 1802, at age seventy-eight, known only as the king’s printer.[xxix] Despite the rumors that circulated after the Revolutionary War, which he likely also heard, Rivington may have been incentivized to play the Loyalist as long as possible. In 1782, Sir Guy Carleton, British commander during the peace negotiations and evacuations, presented Rivington’s two sons, then ages nine and ten, with commissions in the British army. Despite no active service, the boys received half pay for life, which smells of a payoff for Rivington’s printing service to the Crown. Rivington may have wanted his espionage activity kept quiet until and following his death in order to prevent the termination of his sons’ pensions.[xxx] If rumors were circulating in 1784 about Rivington acting as an American agent, why wouldn’t Rivington have embraced the theory even if it wasn’t true? His silence in the face of the gossip reveals that he was still fiercely loyal and/or not wanting to jeopardize his son’s pensions. Perhaps he wanted to double dip and receive pensions for life for his sons and a reward in gold from Washington, if that’s the ounce of truth from Custis.

Today, Rivington’s alleged work as a Loyalist printer slash Patriot spy still raises eyebrows. Most evidence requires dot connecting and reading between the lines. However, the mounting circumstantial evidence is impossible to ignore and the two McLane documents – one in his own hand and one by an unknown author – are persuasive even though they require further examination. No doubt, Rivington has earned a prominent spot in American history for being the most hated Loyalist printer on the continent, but there is clearly a strong probability that he also served as one of America’s top secret agents, playing a critical role in the Siege of Yorktown. For me, the sum of evidence is greater than its parts. The pre-1860 gossip plus Rivington’s compartmentalized placement in the Tallmadge code book plus the three letters by McLane, Peters and an unknown source exposing “Rivington,” “Rivington’s Printing Office” and “R in New York” have proven beyond a reasonable doubt that he was a Patriot spy. The burden of proof should shift to those who think otherwise.

[i] Boston Gazette, March 22, 1773; Rivington’s birthdate is frequently mentioned as 1724 or circa 1724.

[iii] Arthur M. Schlesinger, Prelude to Independence: The Newspaper War on Britain, 1764-1776 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1958), p 225.

[iv] American Archives, series 4, vol 1, p 1051: Committee of Observation for Elizabethtown, in New-Jersey. Resolution relative to Rivington’s Gazette, December 19, 1774: http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgi-bin/amarch/getdoc.pl?/var/lib/philologic/databases/amarch/.1277

[vi] Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, April 20, 1775; New York, New York received the news of the first shots at Lexington at 4 p.m. on April 23, according to Appendix S in David Hackett Fischer’s Paul Revere’s Ride (Oxford University Press, 1994).

[ix] William Hooper to James Iredell, January 4, 1784, Griffith J. McRee, Life and Correspondence of James Iredell… (New York, 1857-58), II, p 84.

[x] Ashbel Green to “My Dear A.” June 30, 1840, The Life of Ashbel Green, ed. Joseph H. Jones (New York, 1849), p 45.

[xi] George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741-1799: Series 4. General Correspondence. 1697-1799. Image 26 of 1096 (http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mgw/mgw4/094/0000/0026.jpg). Despite the Library of Congress dating the code book to 1783, July 1779 is the correct date. Tallmadge preparing the code in July 1779 is referenced in Weber’s U.S. Diplomatic Codes and Ciphers (see note xii) and was narrowed to late July by The Papers of George Washington. Based on an author email exchange with William M. Ferraro, associate editor of The Papers of George Washington, Ferraro wrote: “We have dated the code book later July 1779 because of a letter that Benjamin Tallmadge writes GW on 25 July 1779. That letter begins: ‘enclosed is a Scheme for carrying on the Correspondence in future with C—-. Some directions how to use sd Dictionary may be found annexed…’ The letter with extensive annotation on the code book can be found in The Papers of George Washington, The Revolutionary War Series, vol. 21, p 658-63. The letter is known only from a draft that Tallmadge retained and is now housed with his archive in the Litchfield Historical Society in Litchfield, Connecticut.”

[xii] Ralph E. Weber, United States Diplomatic Codes and Ciphers: 1775-1938 (New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 2010), p 109, fn 10.

[xiii] Samuel Culper, Jr. (Townsend) to Major Benjamin Tallmadge, July 15, 1779, The Papers of George Washington, The Revolutionary War Series, William M. Ferraro, ed., (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2012) vol 21, p 714-15. Townsend wrote “Note a paragraph in Rivingtons paper of the 10th Inst. Under the N.-Yk head, and you’ll observe that something has either leaked out, or they have conjectur’d very right.” Edward G. Lengel, editor of The Papers of George Washington, and his Papers colleagues – William M. Ferraro and Benjamin L. Huggins – were very helpful in the development of this article by providing alternative solutions to the Rivington mystery, including evidence of a sour relationship between Rivington and Washington. Since a healthy Rivington-Washington relationship is not a prerequisite to Rivington acting as a spy, and since Rivington would have worked through an intermediary, I elected to leave that argument out of the article.

[xv] George Washington Parke Custis, Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington, ed., Benson J. Lossing (New York, 1860). The story of Rivington is found on pages 293-299.

[xvii] Catherine Snell Crary, “The Tory and the Spy: The Double Life of James Rivington,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Jan., 1959), p 61-72.

[xviii] Morton Pennypacker, General Washington’s Spies on Long Island and in New York (Brooklyn, 1939), p 4, 12-13. Washington to Benjamin Tallmadge, June 27, 1779, Washington, Writings, XV, 326n. Henry Wansey, The Journal of an Excursion to the United States of North America, in the Summer of 1794 (Salisbury, 1796), entry for June 23, p 206.

[xix] According to Crary, the £100-per-year salary was “only nominal since it was to be paid out of the American quitrents, which could not be collected. Rivington to Richard Cumberland, Nov. 23, 1778, Colonial Office Series 5, Vol. 155, p 172, Public Records Office.”

[xx] Recollections of Allen McLane, Allen McLane Papers, II, 56, New York Historical Society. Crary’s article referencing and picturing the McLane document explained that he returned on August 26, 1781, and did not provide any details about when McLane authored the firsthand account about Rivington, but Crary did mention the account was in his own hand, which would put it somewhere between 1781 and McLane’s death in 1829. In an effort to date the McLane document, the author spoke with the manuscript librarian at the New York Historical Society and learned that item 56 is temporarily removed from the collection (see photo instead in Crary, WMQ) and offered this: “The page in the volume that precedes page/item number 56 contains a variety of documents. There is a collection of diary pages, the last entry of which is Monday, August 23, 1779. There is a list of battles and outcomes, last of which is “Richmond destroyed, 5 July (or possibly January 1781). There is also a long letter dated May 5, 1775. The page following #56 contains a bound group of pages entitled ‘Extract of a Journal, Copies of an association, Commission instructions, Letters of certificate of service.’ The other items are dated 1775, 1777, 1778, 1780 and 1781.” The volume pieces suggest, though not conclusively, that McLane’s letter mentioning Rivington was written not long after it happened, perhaps as a diary entry like the one dated August 23, 1779, in the previous section of the volume.

[xxiii] Washington to Peters, Oct. 27, 1781 (handwriting of Jonathan Trumbull, Jr.), Richard Peters Papers, Hist. Soc. of Pa. See also Washington, Writings, XXIII, p 277.

[xxiv] Crary’s footnote says to “See page 41” of “Extracts of a Journal of Allen McLane,” Recollections of Allen McLane, McLane Papers, II, 57, New York Historical Society.

[xxvi] Catherine Snell Crary, The Price of Loyalty: Tory Writings from the Revolutionary Era (New York, 1973), p 328.

[xxvii] Philip Ranlet, The New York Loyalists, (Knoxville, 1986), p 59. Gouverneur Morris, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, vol 12, (Washington: 1904-1937), p 1061.

[xxviii] Kara Pierce, “A Revolutionary Masquerade: The Chronicles of James Rivington,” Binghamton Journal of History, Spring 2006. http://www2.binghamton.edu/history/resources/journal-of-history/chronicles-of-james-rivington.html.

[xxix] Many of the American newspaper obituaries referenced Rivington as the King’s printer, including the Newport Mercury (July 13, 1802), Baltimore’s Democratic Republican (July 8, 1802), New York Evening Post (July 6, 1802) and several others as found in NewsBank’s America’s Historical Newspapers archive. Other newspapers simply called him “an eminent printer and bookseller.”

[xxx] Charles R. Hildeburn, Sketches of Printers and Printings in Colonial New York (New York, 1895), p 132. The ages of Rivington’s children are based on multiple sources. John, the son of James and Elisabeth Van Horne, was shown to be born in 1773 on ancestry.com. The New York Historical Society references Major John Rivington (ca. 1772-1808) as the son of James and Elizabeth Rivington and acknowledges that he “received a commission in the British army from Sir Guy Carleton” (http://www.nyhistory.org/node/45457). James Jr., the son of James and an unknown spouse, was shown on ancestry.com to have been born in 1769; however, Paul L. Pace, citing “TNA, WO25/772, p140,” found that “Ens. James Rivington was born Aug. 29, 1771, making him about ten when he was commissioned Feb. 28, 1782.” According to Pace, Rivington Jr. exchanged to half-pay Aug 26, 1785 in the 2nd Bn., 84th Regt., or Royal Highland Emigrants. Assuming John also received his commission in 1782 that would make him nine years old at the time.

10 Comments

Mr. Andrlik, your article is the most comprehensive historical research I have seen on this subject. Purely from the perspective of an intelligence officer, it would seem that Robert Townsend (Culper, Jr.) was the individual who recruited Rivington,or accepted him as a volunteer. Specifically when he did so is indeed a mystery but if the development of trust between the two (a key element required in a clandestine relationship considering the serious consequences of exposure) is considered sometime in 1780 would seem right. Townsend did not join the Ring until mid 1779 and in mid 1781 we all seem to agree Rivington provided McLane with the British Navy Signals. I am unsure exactly when Townsend became a business partner with Rivington in the coffee house but such an enhanced relationship, aside from its reporting value to the Ring, would also have provided him to cover for a closer relationship with Rivington. This could mean a deeper degree of cultivation of Rivington as the target, or that the relationship had been established and a cover for action was required for more frequent interactions.

Anyway, the above would be a logical assumption from an intelligence perspective.

From the same perspective, an equally interesting question is why a non Ring member was used to get the Signals from Rivington. McLane certainly was a respected intelligence officer but why established Ring communications procedures were not used to pass that intelligence remains a mystery.

Thanks, Ken. I greatly appreciate the compliment considering your research on the subject. Seems like logical assumptions are primarily what we have when it comes to espionage of the 18th century. Though, since spies went to great lengths to misdirect, we probably shouldn’t be quick to discount the illogical. I look forward to your forthcoming book, Spies, Patriots and Traitors: American Intelligence in the Revolutionary War (Georgetown University Press, May 2014). Love the cover art!

I enjoyed this article the first time I read it. As far as Rivington keeping his spy identity secret, clearly he had little to gain and much to lose by disclosure. It would be interesting to calculate the articles running from before Custis’ claim through the other suggested dates to see whether and how much change may have occurred in the tone of his ‘editorial.’ As said in Hollywood, it might make the perfect sequel.

Interesting story on Rivington. I noticed mention of Rivington’s decline of subscriptions following the 1st Continental Congress. The decline appears to coincide with the publication of Rev Seabury’s first letter from A W Farmer (aka A Westchester Farmer). Seabury’s op ed was very effective and kicked off a pamphlet war with young Alexander Hamilton. However, the fun didn’t stop there. Before the debate was over, Rivington had published about a dozen pamphlets against nonimportation and about six in favor of nonimportation. While the whigs were probably correct in labeling Rivington as a Loyalist, they ignored any concept of freedom in the Press. Instead, in a typical act prior to the revolution, they put together a mob (Isaac Sears) and ran Rivington out of business.

When I read the materials on Seabury, it seemed like the Whigs were less angry about Rivington than they were about the effect Seabury’s pamphlets had on the population in New York and New Jersey. Rivington was willing to print both sides of the issue (I personally think he was more about money than loyalty) and remain true to principles of freedom that would later become part of our Bill of Rights. However, the whigs were not so tolerant. They acted the bully and denied freedom of the press by force of mob rule.

In any event, it looks like Rivington made up for any loss on newspaper subscriptions by printing and selling large numbers of pamphlets on the Nonimportation debate. Probably why Sears became so enraged. The Whig attempt to boycott Rivington’s paper didn’t have much impact.

However, in the end, perhaps Rivington was actually less of a loyalist and more of a journalist simply out to print both sides of political debate. As a result, I am not certain it is really so surprising that he would turn Patriot in the end. After all, the quote from above says it very well:

“The Printer is bold to affirm, that his press has been open to publications from ALL PARTIES; and he defies his enemies to produce an instance to the contrary. He has considered his press in the light of a public office, to which every man has a right to have recourse. But the moment he ventured to publish sentiments which were opposed to the dangerous views and designs of certain demagogues, he found himself held up as an enemy to this country, and the most unwearied pains taken to ruin him. In the country wherein he was born he always heard the LIBERTY OF THE PRESS represented as the great security of freedom, and in that sentiment he has been educated; nor has he reason to think differently now on account of his experience in this country.”

https://allthingsliberty.com/2013/07/reverend-seaburys-pamphlet-war/

Your article on James Rivington took on an even more personal note for me after having read the amount of business correspondence between Rivington and Knox during this past year. Rivington was not an easy guy to figure out, but I just have the feeling he was a man trying to eek out a living in very difficult times; doing whatever he had to. Playing Loyalist printer to the king would help ensure his sons’ pensions. But when the sun went down, he was a top secret agent for The Cause. The logic that you used in this article, in my estimation, does tip the scale to putting the burden of proof on the doubters’ sides and does seem to weight the evidence that Rivington was a patriot spy. Would make a great film or TV screenplay sometime!

Todd: Congrats on an outstanding article. This is great scholarship and analysis on a difficult subject on which to get a handle. Christian

I’ve heard the story about Washington and the bags of gold before but as I heard it, the gold went to Robert Townsend, not Rivington. Is my source wrong or are there conflicting stories? Great article. Thanks for posting

Hi Carolyn! Glad you found the article. The source I cited above [xv] is definitely referencing Rivington as the recipient of the two sacks of gold, but the story, regardless of the recipient, is almost certainly a myth.

Washington never knew, and didn’t want to know, the identities of any members of the Culper network, including Townsend.

Where is the Rivington Coffee House in New York? Is it marked with a historical marker?