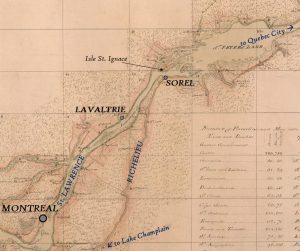

On the third day of November 1775, Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery and his Continental army triumphantly concluded a taxing two-month siege with the surrender of British Fort St. Johns and its 600-man garrison. Their invasion of Canada had finally gained momentum. A week later, the Continentals assembled on the south shore of the St. Lawrence, ready to cross the river and take their next objective, Montreal.

British Governor Guy Carleton had already recognized that Montreal was not tenable. On Thursday, November 7, he ordered his last 150 British regular soldiers, government officials, prominent Loyalists, gunpowder stores, and other military supplies to be loaded aboard eleven sailing ships: the brig HMS Gaspée, armed provincial schoonersIsabella, Maria, Polly, and La Providence, transport schooner Reine des Anges, sloops Brilliant and St. Antoine, and three smaller, unidentified sailing vessels. The governor and his deputy, Brig. Gen. Richard Prescott, embarked on Gaspée to lead the mass evacuation downriver (northeast) to Quebec City.[1]

Once the ships were loaded, however, prevailing winds blew directly from the northeast for several days, hindering departure and making “every British heart tremble” over their fate. The act of sailing a ship directly into the wind on the St. Lawrence was risky—even with the one or two knot current. It required tacking through narrow channels with the risk of grounding on shallows, or having one’s ship stuck vulnerably “in irons,” with no wind in the sails to maneuver.[2]

On Saturday afternoon, November 11, the days of waiting came to an end as flags and weathervanes turned under a cold northwest wind, with snow flurries. Around three o’clock, a single cannon signaled the governor’s flotilla to weigh anchor and set sails for the 170-mile river voyage to Quebec City. The British and Canadian Loyalists fled in the nick of time—Montgomery and his advance guard marched victoriously into Montreal just two days later.[3]

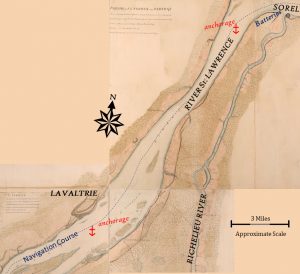

On the first full day underway, the challenges of sailing ships on the river became readily apparent—one of the armed schooners ran aground on a shoal, just a short distance downstream from Montreal. The crew took hours to free the ship and get back underway. Carleton’s eleven ships had only put thirty miles between them and Montreal that day before the winds shifted northeast again. “The elements seemed to conspire” against their timely escape. The fleet sat in anchorage off the north shore parish of Lavaltrie for two days, waiting until advantageous winds returned on Tuesday, November 14. The ships resumed their trip downriver, but only managed to sail another dozen miles before contrary winds, “very violent with heavy snow,” returned that evening. The fleet anchored a few miles short of Sorel, a fifty-dwelling town at the confluence of the Richelieu River.[4]

Carleton and his captains had good reason to wait for favorable winds before attempting to pass the narrows between Sorel and Isle St. Ignace. Just a week had passed since American artillery forced some of the king’s ships away from that very point. Merchant mariner Christopher Prince, piloting HMS Gaspée, observed, “I knew we could not pass the batteries at Sorrel without being sunk by the guns at that fort [battery at Sorel], unless the wind shifted.”[5]

The eleven ships faced this looming encounter with considerable limitations. The flotilla leaders had to worry about the lives of one hundred and forty women and children who accompanied soldiers and officials on board various ships. Capt. François Bellette’s schooner La Providence was a Vesuvian danger of its own, carrying all of Montreal’s gunpowder. The captains included some of the most respected St. Lawrence River navigators; yet they must have had doubts about their merchant-mariner crews’ abilities to sail close-hauled into the wind while facing enemy fire. The armed schooners were nominally able to fight back, having up to sixteen cannon each, but the provincial sailors’ gunnery skills were unproven at best. Even the one proper warship, HMS Gaspée, had only a half crew of fifteen navy sailors—augmented by foot-soldier passengers—to man the sails, six cannon, and ten swivel guns. Gaspée’s captain and the rest of the crew had been detached to Fort St. Johns for Lake Champlain duty before the invasion. These compounding challenges presumably biased Carleton and Prescott toward caution as they approached enemy-held Sorel.[6]

Opposition

The American force awaiting Carleton’s fleet consisted of a couple hundred Continentals and Canadian partisans, flushed with recent victories. They were led by Maj. John Brown, intrepid and seemingly omnipresent in the campaign, and his west Massachusetts Regiment commander, Lt. Col. James Easton. In the week before Fort St. Johns surrendered, much of this composite corps had successfully repelled a Canadian Loyalist detachment that marched from Sorel to relieve that beleaguered British fort. The Loyalist corps retreated back to Sorel and embarked on three armed ships, but lingered off the town. On the night of Tuesday, November 7, Brown led a detachment that quietly built a fascine battery of five 6- to 12-pounder cannon within musket shot of the enemy. When the British ships fired their regular morning gun signal, those aboard were shocked to receive an American reply of “at least 12 Rounds” from the new works. Brown reported that his gunners “plumed” HMS Fell “thro’ in many Places before she . . . slip[p]ed her Cable.” The small British warship fired “briskly” at Sorel as she “made the best of her way down the River out of sight,” sailing down to Quebec City.[7]

In the week after that initial ship-and-shore encounter, Easton amassed additional strength with the conclusion of the Fort St. Johns siege. The rest of his regiment and soldiers from Daniel Denton’s company, 3rd New York Regiment, joined him. American soldiers also hauled additional artillery to Sorel, so Easton established a second battery of three 12-pounders and a single 9-pounder. He left two 6-pounders in the original works. Lt. Martin Johnson arrived to help direct the guns. Johnson was a recently discharged Royal Artillery man, whose technical expertise and leadership stood out while serving with John Lamb’s New York company. Easton also acquired two small armed vessels, brought down the Richelieu after the siege. These were the Continental gondolas Hancock and Schuyler, each mounting one 12-pounder cannon on the bow and twelve swivel guns along the gunwales. The two sixty-foot flat-bottomed boats were sometimes referred to as row galleys, but were also rigged to sail. Easton, Brown, and their men at Sorel were well prepared for the approaching enemy.[8]

Contested Passage

The first test came on Wednesday morning, November 15. Carleton ordered HMS Gaspée and the armed schooner Pollyto “reconnoitre the fort at Sorrel, and see if it was possible” for the flotilla to safely pass. As Gaspée “doubled the point” at Sorel with “starboard tacks on board,” the Americans opened fire, striking the brig. Pilot Christopher Prince reported that it “threw us in such confusion not a gun was fired from us.” The crew of Polly, in trail,heard the thundering blasts and “wore round before she got to the point.” Prince immediately heeled Gaspée around to reverse course, reaching safety upriver in a few minutes. Easton boasted that a British ship was “greatly Damaged” in this encounter, but Prince recalled that everyone on board was unscathed. In any case, the Americans had provided an intimidating display of their ability to defend the Sorel narrows.[9]

Gaspée and Polly only worked about a mile back upriver before whiteout snowfall prompted them to anchor for safety. About one o’clock in the afternoon, the squall abated to reveal that the ships were within a half mile of the southern riverbank. Officers soon spotted men gathering on the shore, but could not determine if they were friend or foe.

That question was answered with a bang as a cannon ball pierced both of Gaspée’s bulwarks. General Prescott immediately ordered Prince to “get the brig out of their reach,” but a pelting of grapeshot and musket balls drove everyone below decks. Brave sailors and redcoat volunteers ventured topside to adjust the sails and get the ships underway, but were repeatedly driven back to cover. A sergeant received fatal wounds. After several attempts, a party managed to “cut the gaskets” and free the sails. Others frantically cut the anchor cables. Gaspée and Pollysoon drifted behind a snowy veil and turned upriver to rejoin the flotilla. In this engagement, the startling shore fire had come from Canadian partisans that Easton had equipped with two long 9-pounders. The detachment, probably led by Capt. Augustin Loiseau, believed they had stopped a British landing attempt.[10]

The Gaspée and Polly had just rejoined the other nine ships nearby when a “floating battery” approached. This was one of the Continental gondolas, manned by Easton’s soldiers, sent to chase the ships. Carleton had already seen enough of his persistent enemy’s capabilities that day. He immediately directed his fleet to run with the wind, returning further upstream. The gondola broke off pursuit when the ships took sail.[11]

The next day, General Montgomery issued new orders from Montreal to put the enemy “between two fires.” He directed Col. Timothy Bedel to lead his New Hampshire Rangers and the Green Mountain Rangers downriver “to harass the enemy in their retreat, and if possible to get possession of any or all their vessels, especially that with the powder . . . [and] . . . to secure the persons of the Governor [Carleton] and General Prescott.” Since all the rangers were at the end of their enlistments, Montgomery added motivation “beyond the letter of the law.” He promised that “all public stores, except ammunition and provisions, shall be given to the troops who take them.” Even with that enticement, the Green Mountain men declined to participate and headed home; their tattered summer field garb was inadequate for the increasingly hostile Canadian winter. Bedel’s men, however, answered the call and marched down the north shore to find the enemy ships anchored off Lavaltrie. By Thursday, November 16, after five days underway, Carleton’s fleet was still just thirty miles from its original point of departure—and now faced threats in either direction: Bedel’s force gathering near the anchorage, and Easton’s at the Sorel narrows.[12]

Negotiations and Surrender

On river and shore, everyone endured very stormy, unpleasant winter weather as they waited in suspense on November 16. Finally, about an hour before sunset, a boat approached the ships off Lavaltrie, under a flag of truce. An American envoy—probably Dr. Jonas Fay—was granted permission to board and asked to speak with Carleton. General Prescott appeared topside instead. He said he was “the only one to transact any business with friends or enemies,” deliberately shrouding Carleton’s presence in ambiguity.[13]

The American delivered a “spirited letter” from Colonel Easton. His message suggested that the British commander “must be very sensible” that “from the Strength of the United Colonies on both sides,” his situation was “Rendered very disagreeable.” Easton proposed “That if you will Resign your Fleet to me Immediately without destroying the Effects on Board, you and your men shall be used with due Civility, together with women & Children on Board.” Prescott asked for time to consider the proposal and the American envoy left in his boat to carry the general’s message to Easton.[14]

About an hour later, a different American officer arrived by boat. It was Maj. John Brown, a more assertive and authoritative agent. Brown and Prescott negotiated in the rapidly fading twilight, agreeing to a truce until the next morning.[15]

Early that night, Carleton summoned his captains to a council aboard Gaspée. The governor detailed their predicament and solicited his officers’ opinions. They all agreed it was imperative for Carleton to reach Quebec City. Capt. François Bellette boldly suggested that the flotilla should fight through the enemy, even though his gunpowder-laden schooner was the most vulnerable. Capt. Jean-Baptiste Bouchette suggested a more cautious course. He promised to deliver Carleton safely downriver by boat. The council favored this option. Early that night, Carleton left Gaspée, joined Bouchette in a whaleboat, and unceremoniously departed the fleet. Bouchette stealthily piloted the boat past the enemy at Sorel in the middle of the night. The Americans failed to capture the governor and remained oblivious to his escape for the next two days. Carleton ultimately reached Quebec City on Sunday, November 19. General Prescott was left to deal with the fleet’s dire circumstances.[16]

The timing and nature of discussions between Prescott and the Americans over most of November 17 and 18 remain obscure. Christopher Prince’s autobiographical narrative provides some great first-hand detail, but by the time he recorded it, his memory had blended three days of negotiations into one. There is one other contemporary description of an episode that presumably happened over this period.

On a trip to Sorel in late May 1776, six months after the surrender, Continental Commissioner Charles Carroll of Carrollton recorded an account he heard from an unnamed source. The individual explained that during negotiations, Major Brown asked Prescott for a British officer to accompany him ashore and verify the threat posed by the American batteries. Once on land, Brown took the redcoat officer to unoccupied battery works upriver from Sorel. The Continental major allegedly deceived him there, saying “two thirty-two pounders” were about to arrive, and ominously warned: “If you should chance to escape this battery, which is my small battery, I have a grand battery at the mouth of the Sorel, which will infallibly sink all your vessels.” By Carroll’s story, it was the returning officer’s testimony following this exchange that convinced Prescott to surrender.[17]

Carroll further suggested that Brown’s threat was entirely a bluff, noting that the Sorel batteries lacked guns of any sort during his visit there, two seasons later. In reality, Continentals had removed the cannon shortly after the surrender and shipped them downriver for the Quebec City siege. Carroll, however, wholeheartedly accepted the account and concluded: “It is difficult to determine which was greatest, the impudence of Brown in demanding a surrender, or the cowardice” of the allegedly hoodwinked officer who persuaded Prescott to capitulate. His assessment has been the most commonly repeated account of the negotiations, effectively dismissing the proven American shore fire capabilities and the fleet’s tremendous weather and navigation challenges. Without direct attribution, or primary source records that corroborate or refute the Carroll story, it should be treated with historical caution.[18]

Whether a redcoat officer had been sent to observe American batteries and report back to Prescott or not, the Continental threat to the fleet manifested in another form. The two gondolas “demonstrated” near the fleet off Lavaltrie. They were probably joined by “field artillery mounted in batteaus” sent down from Montreal by General Montgomery. Despite the marginal size disparity between the well-rigged, deep-draft British sailing ships and squat American gondolas, the latter had the maneuvering advantage and actually had larger (if fewer) guns: 12-pounders against the fleet’s 6- and 9-pounders. Both sides, however, refrained from initiating a river battle.[19]

Resolution came in final negotiations which must have occurred late on the afternoon of Saturday, November 18. Christopher Prince recorded an eyewitness perspective from Gaspée’s deck. Major Brown came shipboard to offer General Prescott the terms one last time. Prescott still said “he could not nor would not sign the proposals.” The American major threatened that the ships would be boarded by force if not surrendered that evening. Then the two held quiet discussions, ending with Brown’s declaration that he would not accept any alteration of the terms. He embarked on his boat, and as his crew pushed off in the dim gloam, the major proclaimed, “I am going on shore, and I think it my duty to tell you that before tomorrow, many of you will [be] enfolded in the arms of death.” The boat had not gone far when Prescott called the American back.[20]

Prescott and Brown re-entered private discussions. After a short while, the American major paced the deck in disapprobation, and began to descend to his boat again. At that point, the forlorn British general finally yielded. Prescott signed the capitulation and agreed to effect the surrender in four hours, at eight o’clock that night. Brown left with a warning: he expected to find the ships and their cargos as he left them.[21]

Prescott, however, had secret guidance from Carleton to follow. The general promptly sent boats to all the ships with orders to “heave overboard all the powder, nearly all the provisions, and a number of other articles.” This act served utilitarian military purposes, but dishonorably violated the surrender terms. Most significantly, Captain Belette dumped hundreds of barrels of gunpowder from La Providence into the river, denying the powder-poor Americans that precious military commodity. Other captains appear to have complied in varying degrees—HMS Gaspée, at one extreme, had only six firkins of butter remaining as provisions, and apparently no ordnance on board, when the Americans seized her; Maria, on the other hand,still had what seems to have been her full cargo the next day.[22]

The ship crews were probably still busy jettisoning cargo when the capricious weather intervened one last time. A “perfect gale” blew from the northwest, keeping American soldiers from coming to seize the vessels that night as arranged. Prescott sent an officer to deliver new orders to all the ships. With the shift of winds, they were “to make every preparation to get underway and follow the brig Gaspée down to Quebec.” Prince warned that it was “impossible to get under way without going on shore when it is so dark and such a gale,” yet Prescott persisted. Prince then recounted that he and some virtuous redcoats subverted or rejected the general’s instructions, refusing to be party to an ignoble violation of accepted capitulation terms. Prescott’s orders met a similar response across the fleet. As a Loyalist described it, second-hand, “the pilots on board the vessels mutinied, and refused to conduct them past the batteries.” The furious general could not cajole the crews into action.[23]

All eleven ships were still sitting at the Lavaltrie anchorage when American boats finally appeared around dawn on Sunday, November 19. The first Continental officer to board Gaspée cursed Prescott for destroying cargo in violation of the surrender terms, having seen the jetsam on his approach. American soldiers took control of the fleet and sealed their remarkable conquest. Gen. Philip Schuyler gave credit to Easton, saying he had “behaved with bravery and much alertness.” As gondola crewman John Philips observed, the eleven British vessels had been taken “partly by stratagem & partly by hard fighting.”[24]

Repercussions

Many contemporaries critiqued Prescott for surrendering without truly testing the American threat. General Montgomery was harshest, writing: “I blushed for His Majesty’s troops! such an instance of base poltroonery I have never met with, and all because we had half a dozen cannon on the bank of the river to annoy him in his retreat!” Canadian Loyalists Simon Sanguinet and Henry Caldwell, and Continental Lt. Ira Allen all shared common sentiments that “the ships might have passed the narrows with little loss.” These perspectives all align neatly with Charles Carroll’s oft-cited contention that John Brown completely bluffed Prescott into an otherwise unwarranted surrender. None of these assessments, however, were directly informed by shipboard perspectives, and Caldwell judiciously conceded: “there must have been some circumstances with which we were unacquainted.”[25]

Mariner Christopher Prince’s eyewitness account from Gaspée—not publicly available until the mid-twentieth century—complicated the traditional interpretation of the affair and surrender. Prince detailed the fleet’s manifold challenges: adverse and unpredictable weather, inadequately crewed ships, precious passengers and dangerous cargos, and the repeated American demonstrations of shore fire accuracy. Given this narrative context, the British capitulation seems far more reasonable.

It is also noteworthy that no one at the time seems to have publicly called the governor or general to account for the fleet’s capitulation. It certainly helped that the first news to reach London provided scant details, and by the summer of 1776, word of Carleton’s obstinate Quebec City defense and the British recovery of Canada swept the Lavaltrie surrender into insignificance. Prescott’s military career did not suffer, either. He was promoted to major general (in North America) while still held by the Continentals, and promptly returned to active service after a prisoner exchange.[26]

For the Americans, the fleet capture categorically delivered immediate and substantial operational gains. General Montgomery used the sailing ships to rush hundreds of troops downstream within days, rendezvous with Benedict Arnold’s corps, and blockade Carleton at Quebec City early in December. With the ship cargos, Montgomery outfitted Arnold’s ragged corps with new redcoat uniforms, fed his men British provisions, and equipped his soldiers with military tools to fortify positions around the enemy-held city.

As a second-order effect, Montgomery’s access to river transport helped lure him into strategic overreach. Loyalist Simon Sanguinet was “certain that if the eleven ships had not been taken—that [Montgomery] would not have been able to go to Quebec, because he would have lacked everything.” Even if Sanguinet exaggerated, an absence of maritime lift would presumably have given the American commander pause to consider before he doubled the length of an already-tenuous supply line between Fort Ticonderoga and his front-line troops. Montgomery, who died in a failed New Year’s Eve attempt to take Quebec City, left his men in an unsustainable logistical position. The ships could not operate on the frozen St. Lawrence from December to mid-April, and land transport proved completely inadequate to the task.[27]

The ill-supplied and poorly reinforced army hung on until May 6, 1776, when it collapsed like a house of cards upon the arrival of British reinforcements that relieved Quebec City. In the Americans’ chaotic flight, British forces promptly recovered the river navy and returned the ships to their own use. Of particular note, the armed schoonerMariaand one of the abandoned Continental gondolas—renamed Loyal Convert—were transported up the Richelieu to serve on Lake Champlain. They were part of the British fleet at the Battle of Valcour Island that fall.

Surprisingly, the Lavaltrie victory also failed to boost the promising careers of the key American players, but embroiled them in controversy instead. Lt. Col. James Easton, despite having been recognized for his “diligence, activity, and spirit,” was imprisoned for debt in April 1776—still awaiting the substantial prize-money payment for the ships’ cargos. Maj. John Brown went to join the Quebec City siege, but found himself under Benedict Arnold’s command after Montgomery’s death. Long-smoldering personal enmities took flame when Arnold publicly accused Brown and Easton of “plundering the Officers Baggage taken at Sorell, Contrary to Articles of Capitulation, and to the great scandal of the American Army.” Brown and Arnold exchanged vicious recriminations throughout 1776. Brown resigned from Continental service in early 1777, war-worn and completely exasperated by the unresolved insults to his honor. He did, however, continue to bravely and effectively serve the American Cause as a Massachusetts officer. Easton, unable to get a court of enquiry to officially clear his name from Arnold’s accusations, was sidelined as a supernumerary colonel, without command. He remained in this limbo state for three years before ultimately being dismissed. Both Brown and Easton suffered grievously from the bureaucratic incompetence of the Continental confederation, and from senior leaders’ failure to properly reward their contributions or resolve the Arnold controversy.[28]

The ripples of direct and indirect effects from the capture of “eleven Sail of British vessels” on the St. Lawrence are just one previously-neglected aspect of that affair in the Revolutionary War historiography. Careful re-examination of primary sources complicates the common narrative that victory hinged on an audacious Yankee bluff, especially with the integration of Prince’s autobiography. The expanded documentary record reveals that Montgomery, Easton, and Brown skillfully employed Continental forces to exploit the opportunity presented by weather contingencies, pressed their worn and vulnerable British enemy, and secured a significant American victory on the St. Lawrence.[29]

[1]Christopher Prince, The Autobiography of a Yankee Mariner: Christopher Prince and the American Revolution, Michael J. Crawford, ed. (Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 2002),53-54; November 14, 1775, Benjamin Trumbull, “A Concise Journal or Minutes of the Principal Movements Towards St. John’s,” Collections of the Connecticut Historical Society, volume 7, (Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 1899), 164-65; Return of Provisions on board the several Vessels under the command of Brigadier-General Prescott, November 19, 1775, Peter Force, ed., American Archives. 4th [AA4] and 5th [AA5] Series (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1837–53), AA43:1693. Colonel Prescott was breveted as a brigadier general for North American service.

[3]Guy Carleton to Earl of Dartmouth, November 20, 1775, K. G. Davies, ed., Documents of the American Revolution, 1770-1783(Dublin: Irish University Press, 1976), 11:185 (Carleton Account); Aaron Barlow Journal in Charles B. Todd, “The March to Montreal and Quebec, 1775,” American Historical Register2 (March 1895): 648; November 11, 1775, Trumbull, “Journal,” 162-63.

[4]Carleton Account; Prince, Autobiography, 54-55; Amable Berthelot, “Extraits d’un Mémoire de M. A. Berthelot sur L’Invasion du Canada en 1775,” in Hospice-Anthelme Verreau, ed., Invasion du Canada: Collection des Mémoires Recueillis et Annotes (Montréal: Eusèbe Senécal, 1873), 233 (author’s translation); November 15, 1775, Trumbull, “Journal,” 166-67.

[5]Carleton Account; Prince, Autobiography, 50-51, 54.

[6]Prince, Autobiography, 45, 46, 50, 51, 53; John Brown to Richard Montgomery, November 8, 1775, William B. Clark, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution [NDAR] (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 1964-), 2:922; Berthelot, “Mémoire,” 233; Return of Ordnance . . . on board the different Vessels, November 20, 1775, and A List of the Officers of His Majesty’s Troops on board the Vessels near Montreal, November 21, 1775, AA43: 1693-94. Prince reported fourteen to sixteen guns on the schooners, yet only two each were reported as captured on Isabellaand Maria(none on the others). Most may have been dumped overboard before the surrender. Prince’s memory of the numbers might also have been inaccurate and/or included swivel guns.

[7]Montgomery to Philip Schuyler, November 3, 1775, and Brown to Montgomery, November 8, 1775, NDAR2:867, 922; Levi Miller S13937 p3-4 and Moses Bartlett S28630 p8, RG15 M804 Pension Records [M804], National Archives and Records Administration [NARA]; “Narrative of Uriah Cross in the Revolutionary War,” Vernon Ives, ed., New York History: Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association 63, no. 3 (July 1982), 288.

[8]November 15, 1775, Trumbull, “Journal,” 146, 166-67; Montgomery to Schuyler, November 17, 1775, Schuyler to Benjamin Franklin, August 23, 1775, and November 21, 1775 entry, Journal of Robert Barwick (Berwick), NDAR 2:1056, 1: 1217, 2: 1104; Orasmus Holmes S2621 p8-9, John Williamson S11784 p6, and Garret Reed S14257 p3-4, M804; Calendar of N.Y. Colonial Manuscripts Indorsed Land Papers, 1643-1803 (Albany: Weed, Parsons, & Co., 1864), 870; Minutes of the Ordnance, AA44: 534.

[9]Prince, Autobiography, 55; November 16, 1775, Trumbull, “Journal,” 167-68; Carleton Account; Simon Sanguinet, “Témoin Oculaire de l’Invasion du Canada par les Bastonnois: Journal de M. Sanguinet,” in Verreau, Invasion du Canada, 87; Berthelot, “Mémoire,” 233; Precis of Operations on the Canadian Frontier, CO 5/253, 26-27, MG-11-CO5, Library and Archives Canada. Some accounts mentioned fire from a battery on Isle St. Ignace, opposite Sorel. American accounts do not mention any such works. Perhaps gondola fire near the low island was mistaken for shore fire.

[10]Prince, Autobiography, 56; Carleton Account; Schuyler to Cornelius Wynkoop, January 7, 1776, NDAR3:670; November 16, 1775, Trumbull, “Journal,” 168; Levi Miller S13937 p4, M804; Petition of Augustin Loiseau, r158, i147 v3, p410, RG360, M247 Papers of the Continental Congress, NARA.

[11]Jonathan Curtis W18986 p12-14, Levi Miller S13937 p4, and Daniel Beeman W17295 p11, M804; Carleton Account; Sanguinet, “Temoin Oculaire,” 86-87; Ira Allen, History of the State of Vermont (originally The Natural and Political History of the State of Vermont. . . [1798]) (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1969 reprint), 49-50.

[12]Montgomery to Timothy Bedel, November 16, 1775, W. J. R. Saffell, ed., Records of the Revolutionary War . . . (Philadelphia: G. G. Evans, 1860), 27-28; Montgomery to Schuyler, December 5, 1775 and November 17, 1775, NDAR 2:1277 and 1056; Thomas Ramsey S15609 p8, Nathaniel Eastman W22992 p4, William Greenough S8613 p4, Benjamin Martin S22376 p8, Isaac Stevens S11460 pp 6 and 13, John Waters W25905 p7, Job Moulton W16656 pp 5 and 43, Thomas Spring S3965 pp 10 and 25, M804; “History of 1776,” The Scots Magazine, October 1777, 521.

[13]Prince, Autobiography, 56-57; Allen, History, 50; Berthelot, “Mémoire,” 234. Ira Allen’s account says “the writer” delivered the letter; historians have generally interpreted this to mean Allen, author of the History, but in context, it appears to mean Fay, writer of the surrender proposal.

[14]Allen, History, 50; James Easton to General Carleton or Officer commanding the Fleet in St. Lawrence, November 15, 1775, Historical Section of the General Staff (Canada) , ed. A History of the Organization, Development and Services of the Military and Naval Forces of Canada, . . .(Quebec: 1919), 2: 127.

[16]Carleton Account; Berthelot, “Mémoire,” 233-34; Prince, Autobiography, 62.

[17]Journal of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, during His Visit to Canada in 1776 . . ., Brantz Mayer, ed. (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1844), 97. The story could not have come directly from Brown, who was operating west of Montreal, nor from Easton who was in Philadelphia during Carroll’s Sorel visit. The largest guns reported at Sorel were 12-pounders; the largest American-held guns in Canada at the time were 24-pounders; Minutes of the Ordnance, AA44: 534.

[18]Carroll, Journal, 97; Robert Barwick Journal, NDAR 2:1151-52.

[19]Berthelot, “Mémoire,” 234; Richard Montgomery to Philip Schuyler, Montreal, November 17, 1775, AA4 3:1633; Daniel Beeman W17295 p1, M804; “History of 1776,” Scots Magazine, October 1777, 521.

[20]Prince, Autobiography, 57-58; Allen, History, 50; Berthelot, “Mémoire,” 234.

[22]Prince, Autobiography, 59; Berthelot, “Mémoire,” 234; Return of Ordnance, and Return of Provisions, November 19 and 20, 1775, AA43:1693.

[23]Prince, Autobiography, 59-63; Henry Caldwell to [James Murray], June 15, 1776, The Invasion of Canada in 1775: A Letter Attributed to Major Henry Caldwell (Quebec, 1887), 4.

[24]Prince, Autobiography, 63-65; Philip Schuyler to George Washington, November 28, 1775, AA43:1692; John Philips S9457 p8, M804.

[25]Richard Montgomery to Janet Montgomery, November 24, 1775, in Louise L. Hunt, ed., Biographical Notes concerning General Richard Montgomery together with Hitherto Unpublished Letters (Poughkeepsie: News Book and Job Printing House, 1876), 15; Allen, History, 50; Sanguinet, “Temoin Oculaire,” 86-87 (author’s translation); Caldwell to [Murray], June 15, 1776, The Invasion of Canada in 1775, 4.

[26]J. Almon, The Remembrancer. . . for the Year 1776, part 1, (London, 1776): 131, 234; “History of 1776,”The Scots Magazine, October 1777, 521, also March 1776, 167 and February 1776, 93. Prescott was embroiled in a separate controversy when the Continental Congress kept him in close confinement as retribution for his mistreatment of captive Ethan Allen in the fall of 1775.

[27]Sanguinet, “Temoin Oculaire,” 88-89.

[28]Easton to Hancock, May 8, 1776, AA45:1234; Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, ed. Worthington C. Ford et al. (Washington, D.C., 1904-37),April 26, 1776, July 16, 1779, and August 22, 1786, 4: 312, 14: 843, 31:553; Benedict Arnold to Hancock, February 1, 1776, NDAR 3:1072, 1074; Petition of John Brown, June 26, 1776, AA5 1:1219-20. Brown successfully raided British-held Fort Ticonderoga in 1777 and died on the battlefield at Stone Arabia in 1780.

3 Comments

Interesting and original article Mark. Do you know how many cannon some of the British ships carried? In my Rhode Island Campaign book, I describe the scuttlings by the Royal Navy in Narragansett Bay in 1778 of four 32-gun frigates, 1 28-gun frigate, two 14-gun sloops, and three armed galleys. I argue that in terms of cannon, it was the most substantial, single campaign loss of warships suffered by the Royal Navy in the war (210 cannon). The British also sacrificed thirteen transport vessels.

The bottom line is that my sources don’t give any solid answers, but 70 is the extreme high end. That number is extrapolated from the Royal Navy-reported armament on HMS Gaspée (6x 6#) and Prince’s narrative that described 16 guns each on Polly and Isabella, with that number applied to Maria and La Providence, too. That high-end guesstimate does not include swivel guns. The Continental reports of captured ordnance are not helpful, listing just two guns each on Isabella and Maria – which may have been carried as cargo below deck.

Hello, I try to find information about the Brig Schooner “Polly”, 14 guns, british ship on St-Lawrence River in Québec Canada during American Revolution. I know that the Polly stopover in Quebec City around April 10th 1780. Who was the captain of the Polly ? Crew and Passengers lists available ? Any information about this ship would be welcome, for years 1780-1781-1782.

Same questions about the Provincial Arm’s Cutter “Jack”, 14 guns, 4 swivels.

Thank you very much for your help !