The graphic below outlines the force structure created by the Third Virginia Convention in August 1775 and identifies the district and county or counties where companies formed, unit commanders, and where and when the companies assembled, served or operated in 1775.

The initial intent of this research was to identify the regular companies that served in the campaign south of the James River to eject Virginia’s royal governor, Lord Dunmore, from the colony. In the process the author identified additional regular companies as part of Virginia’s 1775 security structure. These companies comprise Virginia’s total regular contribution of the districts and counties, and highlights the complex, geographically diverse and evolving security environment confronting Virginia’s political leaders in 1775. This structure does not include modifications introduced by the December 1775 Ordinance (Fourth Virginia Convention) to expand the 1st and 2nd Virginia Regiments to ten companies each and expand the force by adding six additional regular regiments, plus the 9th Regiment for the Eastern Shore service, for a total of nine regiments. Most of the changes implemented in the December Ordinance had little impact on capacity of the regular fielded forces through March 1776. The focus of this analysis is the regular companies, and not the minute battalion and militia structure also authorized in August 1775.

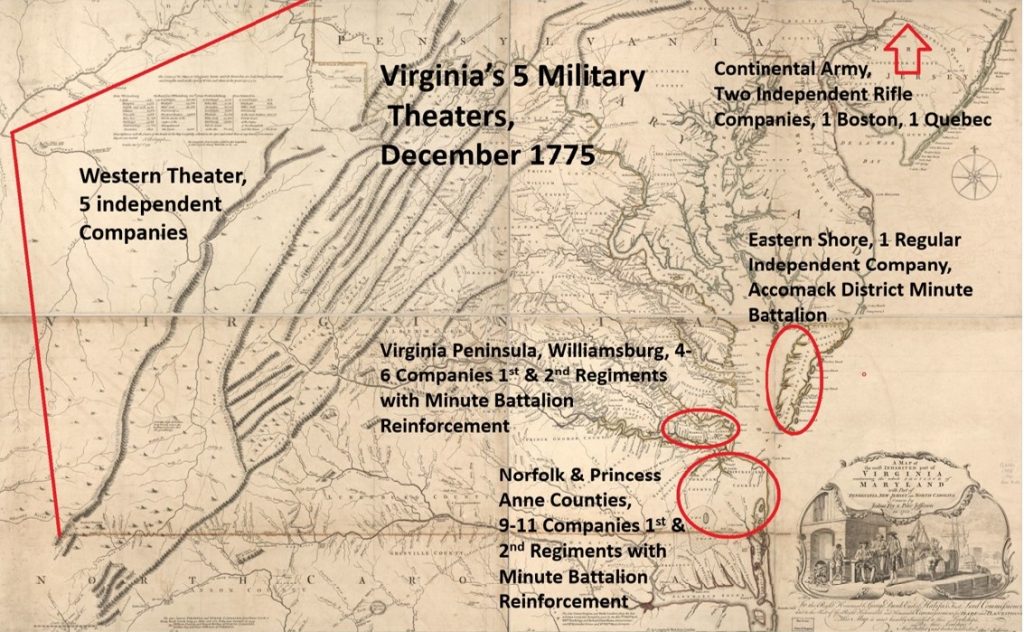

These twenty-three regular companies operated in five geographically separated theaters. The 1st Virginia regiment and one company of the 2nd Virginia Regiment initially operated on the Virginia Peninsula as a security force, with Williamsburg as a base of operation. Nine companies and very likely elements of eleven companies from these two regiments (the regiments consisted of fifteen companies total), operated south of the James River, primarily in Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties, directly attacking Lord Dunmore’s forces. The James River, patrolled by British naval vessels, separated these units operating both north and south of the river. Collectively, these companies served as part of a military force created to remove Lord Dunmore, the Virginia’s royal governor, from Hampton Roads and provide security to Virginia’s capitol in Williamsburg, securing Virginia’s Whig government.[1]

The Eastern Shore presented a challenge because of its location and the fact that Virginia had a limited maritime capability. While the structure provided for units assigned to duty exclusively on the Eastern Shore, including the one regular company, the area remained subject to security concerns and exposure to maritime raiding because of its separation from the rest of Virginia by water, extensive shoreline, and difficulty in recruiting the authorized units. The Accomack District Committee actually elevated the problem of security on the Eastern Shore to the Continental Congress; the security problem was not solved during 1775.

The security of the northern and western portion of the colony (basically the Ohio River extending south to the Holston River line) presented another difficult problem. The final peace treaty with the Shawnee, Delaware and Mingo, tentatively agreed to as Dunmore’s War ended in 1774, remained unresolved as the Patriots ousted Lord Dunmore from power in 1775. Negotiations with these tribes at Fort Pitt in 1775 resolved some outstanding issues but military forces in the form of independent companies helped demonstrate a capability to reengage militarily if the political arrangements did not maintain the peace.

Virginia’s western border also shared a political boundary with the Cherokee, essentially creating a 500-mile northern and western front extending from modern Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Kingsport, Tennessee, and westward. The front became the military responsibility of five Independent Companies. The presence of these companies bought some time before warfare again erupted on the northern and in the western borders of Virginia.

Two rifle companies, formed in the western portion of Virginia, made up Virginia’s initial contribution to the Continental Army surrounding Boston. Capts. Hugh Stephenson and Daniel Morgan commanded these two units. They were part of the Continental Congress’s initial effort in June 1775 to create a national rather than regional army around Boston. Stephenson’s company operated around Boston while Morgan accompanied Benedict Arnold to Quebec and was captured in the failed assault on the city as the year 1775 ended.

In addition to the endnotes that elaborate on details in the graphic, several colors highlight additional information. Orange indicates districts tasked to field rifle units instead of units armed with muskets. It was initially somewhat surprising to find that twelve of the original twenty-three companies, or 52 percent, were armed with rifles; as the war progressed, deference was for muskets. This early use of rifles was likely a practical solution to the problem of a lack of available weapons to arm the force.[2] There was also a disproportionately larger contribution by the western districts of Berkley, Pittsylvania and West Augusta, contributing a total of ten of the twenty-three companies, or 43 percent of the force.

The color Green identifies the six companies of the 2nd Virginia Regiment that participated in the Battle of Great Bridge on December 9, 1775, the first major battle on Virginia soil. The color Blue identifies the companies of the 1st Virginia Regiment that reinforced William Woodford’s task force south of the James River just several days after the Battle of Great Bridge and participated in the occupation and destruction of the City of Norfolk in January and February 1776. The two companies highlighted with Purple likely reinforced the 2nd Virginia Regiment south of the James during the occupation and destruction of Norfolk, but the primary source evidence discovered to date (principally in the form of surviving pension records) is not as clear and convincing as exists for the other three companies of the 1st Regiment. Portions of or possibly the entirety of these two companies did operate as part of the task force in and around Norfolk, after the Battle of Great Bridge.

[1]William Waller Henning, Statutes at Large Being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia (Richmond: Samuel Pleasants Jr., 1809), 9, 9-35& 75-92 & 274-5n7-14.

[2]Perhaps we find the roots of the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in these circumstances. Influential Virginian Richard Henry Lee, one of Virginia’s Delegates to the Second Continental Congress, and later an advocate of the Bill of Rights, wrote, “To preserve liberty, it is essential that the whole body of the people always possess arms, and be taught alike, especially when young, how to use them.” “Richard Henry Lee Biography,” www.biography.com/political-figure/richard-henry-lee.

[3]The August Ordinance creating Virginia’s military structure specified districts and counties tasked with forming and manning units, several districts were directed to man units with riflemen vice musket men. Each district, minus Accomack, provided one regular company, assigned to either the 1st (eight companies) or 2nd (seven companies) Virginia Regiments. Only six of the seven companies of the 2nd Virginia Regiment operated south of the James River, the seventh company conducted security operations on the Virginia Peninsula. Multiple companies of the 1st Virginia Regiment reinforced the 2nd Regiment south of the James River. The Berkeley District provided two rifle companies as directed by the Continental Congress for service in the Continental Army forming around Boston prior to the August Ordinance (see note 13 below). Several districts were tasked to form and man independent frontier companies. Each district, minus Accomack, was tasked to form a minute battalion of 500 men in ten companies. The ordinance directed each county to form militia companies of 32 to 68 men and include those from the ages of sixteen to fifty. Four districts provided minute forces to reinforce Woodford’s six regular companies of the 2nd Virginia Regiment (430 officers & men) south of the James River in the campaign to eject the royal governor from Virginia. These were the Culpeper (Battalion headquarters and five task organized companies, 287officers & men), Princess Anne (elements of multiple companies, numbers and leadership unknown), Amelia (two companies, likely Captains Carrington & Jones) & Southampton (multiple companies, Captains Mason, Wall and possibly others unidentified, 180 officers and men, Maj. John Ruffin, commanding). Journals of the Convention, August 1775, Ordinances29-37, www.google.com/books/edition/_/bQEtAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1; Scribner and Tarter, eds., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, Scribner & Tarter, eds. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1973-1983), 5:82 n20, 224n39, 242, 244n9, 368-9; author, multiple pension applications. E. M. Sanchez-Saavedra, A Guide to Virginia Military Organizations in the American Revolution, 1774-1787 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1978), 22, correctly identifies Ruffin from the Southampton District; Scribner & Tarter incorrectly identify him from Amelia District. Ruffin’s Southampton District detachment arrived in Norfolk on December 24, 1775. The two Amelia District companies arrived Norfolk on or about January 3, 1776. Revolutionary Virginia, 5:330.

[4]Henning, Statutes, 9, 13; Journals of the Convention, August 1775, Ordinances. 31, www.google.com/books/edition/_/bQEtAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

[5]Sanchez-Saavedra, A Guide to Virginia Military Organizations, 30-31 & 36, verified against multiple pension records in revwarapps.orgby the author; Sanchez-Saavedra, 36, incorrectly identifies William Fontaine from Amelia District, Amelia County, actually Buckingham District, Amherst County. Brent Tarter, “The Orderly Book of the Second Virginia Regiment: September 27, 1775-April 15, 1776,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 85, 2 (April 1977), continued in 85, 3 (July 1977), 171 n47 and 302; Sanchez-Saavedra, 36, incorrectly identifies George Nicholas from Henrico District, Hanover County, actually Elizabeth City District, City of Williamsburg, he was the son of the Treasurer of the Colony of Virginia, Robert Carter Nicholas.

[6]Southern Campaigns, Company Officers of the First and Second Virginia Regiments in 1776, Rosters, B143, revwarapps.org/#rosters.

[7]Author, Southern Campaigns, Pension file research, revwarapps.org, multiple records.

[8]Ibid.; 2nd Virginia Orderly Book identifies the 1st Virginia Regiment detachment that reinforced Colonel Woodford on December 12 at Great Bridge and led by Maj. Francis Epps as the companies of Markham, Ballard & Davies; pension files support the 3rd company as John Fleming vice William Davies; Fleming’s name appears in the 2nd Virginia Orderly book on December 24, 1775 (p. 310, when he was placed under arrest by Major Epps). Davies name first appears in Norfolk on December 25, 1775 in reference to court marital charges against Lieutenant Boykins for deserting his post (p. 311). While Fleming’s company is represented by multiple pension records indicating campaign service at Norfolk, Davies’ is not. Elements of both companies did serve south of the James River, along with others from the 1st VirginiaRegiment as mentioned above in the Orderly Book.

[9]“The Orderly Book of the Second Virginia Regiment,” 318n106; both Green and Davies were in Norfolk on January 22, 1776.

[10]Revolutionary Virginia, 4: 274-5n7; “The Orderly Book of the Second Virginia Regiment,” 170-71.

[11]“The Orderly Book of the Second Virginia Regiment,” 169-171, details some company arrivals; multiple pages/entries consulted, supported by the author’s pension application research.

[12]Revolutionary Virginia, 4:274-5n7.

[13]Two minute companies were ordered trained as regulars because of the exposed nature of the Eastern Shore. Journals of the Convention, August 1775, Ordinances. 31-2, 35, www.google.com/books/edition/_/bQEtAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1. On December 7, 1775, the convention ordered the three activated Accomack District companies, one regular and two minute, to consist of riflemen vice musket men. Revolutionary Virginia, 5:72. Recruiting problems prevented filling the minute companies and battalions. Ibid., 4:247n3, 498. Because of the constant threat by maritime forces of Lord Dunmore, county and Accomack District representatives of the exposed Eastern Shore corresponded directly with the Continental Congress as well as the Virginia Convention. Ibid., 4:467-8, 473n5.Ultimately, during December 1775, the Convention authorized a ninth regiment of regulars for duty in the exposed Accomack District (see note 1 above); several companies were recruited during early 1776 in the Buckingham and Henrico Districts for Eastern Shore service, reflecting difficulty in generating the necessary interest in volunteering for any type of service in the Accomack District. Sanchez-Saavedra, A Guide to Virginia Military Organizations, 59.

[14]Virginia formed and deployed two rifle companies during June and July 1775, based on a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, to build a multi-colony presence in New England and supply the forming Continental Army with riflemen capable of killing the enemy at 250 yards. Both were from what would in August become the Berkeley District. Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress, II (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1905), 89-90; Patrick H. Hannum, “America’s First Company Commanders,” Infantry (Oct-Dec 2013), 12-19, www.benning.army.mil/infantry/magazine/issues/2013/Oct-Dec/pdfs/OCT-DEC13.pdf.

[15]Tucker F. Hentz, Unit History of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment 1776-1781, Insights from the Service Record of Capt. Adamson Tannehill (Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 2007), 2-4, virginiahistory.org/sites/default/files/uploads/tann.pdf; Francis Bernard Heitman, Historical Registrar of Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution (Washington: The Rare Book Shop Publishing Co. Inc., 1914), 401, 518.

[18]A special thanks to author Gabriel Neville for his research on the Independent Frontier Companies. Four of the five Independent Frontier Companies faced northwest guarding against a confederation of Native American tribes including the Shawnee, Delaware and Mingo who, in 1775, were still in the process of formal negotiations to end Dunmore’s War. A tentative treaty ended hostilities in 1774; without a formal treaty in 1775, continued conflict on the frontier was a distinct possibility. The Virginia Conventions expended significant effort to conclude and sustain a peace treaty during 1775. The first West Augusta Independent Frontier Company was actually formed in Winchester, Frederick County. Sanchez-Saavedra,A Guide to Virginia Military Organizations, 81; Gabriel Neville, “Virginia’s Independent Frontier Companies, Part 1 of 2,” Journal of the American Revolution, March 21, 2021, allthingsliberty.com/2021/03/virginias-independent-frontier-companies-part-1-of-2/.

[19]Revolutionary Virginia, 3:404, 405n3, 4:15, 197-202; Neville, “Virginia’s Independent Frontier Companies.”

[20]Sanchez-Saavedra,A Guide to Virginia Military Organizations, 81.

[21]The Independent Southwest Frontier Company faced the Cherokee frontier that bordered the entire southwestern portion of the Colony of Virginia extending west into modern Tennessee and Kentucky.

[22]Neville, “Virginia’s Independent Frontier Companies.”

[23]The Point Pleasant Company eventually manned Point Pleasant, the site of the 1774 battle during Dunmore’s War. The company formed in the fall of 1775 and wintered at Savannah Fort, modern Lewisburg, West Virginia, before obtaining supplies at Fort Pitt and floating downriver to rebuild Fort Randolph during the spring of 1776. Neville, “Virginia’s Independent Frontier Companies.”

[25]Reassigned to the 8th Virginia Regiment in 1776. Ibid.

[26]The district and county for this twenty-five-man company are not recorded and it may be best described as an independent detachment linked to Fort Pitt because of the proximity. Ibid.

6 Comments

Nice job describing the complexity of Virginia’s military structure in 1775. Concerning your “purple” comments on Culpeper County, both William H.B. Thomas (Patriots of the Upcountry: Orange County, Virginia in the Revolution) and E.M. Sanchez-Saavedra (“All Fine Fellows and Well-Armed: The Culpeper Minute Battalion, 1775-1776” in the Virginia Cavalcade, Summer 1974) claim that some of the Culpeper companies were at Great Bridge, though without specific references.

Any mention of the Battle of Great Bridge should mention the 150 men from the Halifax (NC) District Brigade and another 150 or so men from the Edenton (NC) District Brigade, both militia formations. The Edenton Brigade included men from Currituck, Camden/Pasquotank, and Chowan, with perhaps some from Gates counties. The Perquimans contingent arrived on Dec. 10. Additionally, Col. Robert Howe was on the way with the 2ND NC and an artillery train. His guns went a long way toward persuading Dunmore to abandon Norfolk. However, Howe technically outranked Woodford, which led no doubt to some tense moments between the two. It is good to see someone going through the pension applications concerning Great Bridge, as there is a wealth of information in there.

Elmer, Thanks, you are correct. However, North Carolina forces played a much greater role in the 1775-76 campaign after the Battle of Great Bridge. This article focused on Virginia’s regular force structure in multiple theaters in 1775. North Carolina forces were present at Great Bridge on 9 Dec 1775. Woodford’s 10 Dec 1775 personnel report indicates there were 180 North Carolina troops present at Great Bridge. There is no accounting of the unit designation, reported only as “Carolina Forces.” Woodford leaves no accounting of Virginia militia, but we know some were present as well. Concerning North Carolina, Woodford refers to a Col Wells before the battle in his correspondence. Col Vale’s name also appears as well as Peter Dozier, also spelled Dauge. Woodford’s report lists 1 Lt Col, 1 Maj, 5 Capts, 4 Lts, 3 Ensigns from North Carolina. One of the Captains is William Goodman (referenced on a pension statement by another Virginia militia officer). Pension research to date identifies 11 men from North Carolina who were likely at Great Bridge on 9 Dec. Virginia and North Carolina militia records and pension applications are thin. Most of the North Carolina forces identified to date are 2nd North Carolina Regiment men who arrived on the 12th. Because this was only a 6-month initial enlistment (Sep 75-March 76), these records are also thinner than for the 2nd Virginia Regiment, (1-year enlistments). Interested in any primary of secondary sources you would be willing to share, most of my research to dated has focused on Virginia. Please contact the JAR editor who can link us up.

Thanks Bill, There were five Culpeper Companies at Great Bridge. Will address these companies in a future article. Culpeper prepared and deployed their minute companies as a battalion, more quickly and professionally than the other districts. Makes the Culpeper contributions stand out over the other districts. There were 287 Culpeper men at Great Bridge, they made up about a third of the task force. The battalion and companies were clearly well-led and contributed significantly to the Patriot success at Great Bridge.

Thank you for your article. I have found publications on the similar subject of the Northern states easy to find, in comparison to what is available about the Virginia’s military during that time. I appreciate your hard work!

My 3rd great-grandfather William Rhodes (1745-1825) enlisted as a private at Alexandria, VA 1st Sept. 1775 into the 2nd Virginia Regiment, under Captain George Johnston. William referred to Johnston’s unit as the first company of the 2nd Virginia (according to his pension). I recall years ago reading an account by Capt. Johnston about a skirmish at Norfolk, which occurred before the battle of Great Bridge in 1775. My question for you is, if William enlisted into the 2nd VA on 1st September 1775, what action may have he seen during 1775 to mid 1776?

Carl, Thank you for this information. Working in conjunction with the Great Bridge Battlefield Waterways and History Foundation. Researching and compiling a data base for soldiers who fought in the 1775-76 Virginia Campaign, to include the 2nd Virginia Regiment, and did not have William’s name listed, likely because he did not specifically state in his pension application he was at the Battle of Great Bridge or the destruction of Norfolk. During 1775 and early 1776 he would have been in both of these actions as a member of George Johnston’s Company. With a commissioning date of September 21, 1775, Johnston was the senior company commander in the 2nd Regiment. The action at Norfolk followed Great Bridge. If you contact the JAR editor by email, he will link us up by email so we can communicate in more detail. Thanks again. Pat