If the headline of a January or February 1776 edition of any North American Tory newspaper read, “Norfolk, Virginia, Sacked by North Carolina and Virginia Troops,” it would not have constituted propaganda. Loyalists in Tidewater Virginia, under the leadership of Lord Dunmore, Virginia’s Royal Governor, were under siege by rebel Whig or Patriot troops from the colonies and future states of North Carolina and Virginia, under the military leadership of a North Carolinian, Robert Howe.[1] The actions of Howe, operating under both Convention and North Carolina authority, and William Woodford, the senior Virginian, and their troops proceeded with the approval and consent of the North Carolina and Virginia provisional governments.[2] The provisional Whig governments formed military units to protect their interests and challenge the military capabilities of the royal governors. Howe’s soldiers, tasked with the destruction of Norfolk, the largest city in Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay region, performed their task with rigorous efficiency.[3]

The Whig’s systematic and deliberate destruction of Norfolk denied the British a capable military base of operations in the southern Chesapeake Bay, and complicated future British military operations in the region. As a result, Virginia provided critical economic, manpower, military, and logistical support to the Whig or Patriot side in American Revolution largely unimpeded until 1779.[4] The destruction of Norfolk proved a crucial decision with far reaching strategic military consequences that sowed the seeds of the British defeat at Yorktown in October 1781.

The Importance of Norfolk in Relation to the Chesapeake Bay

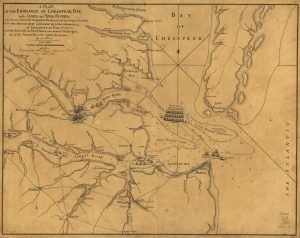

In 1775, Norfolk, Virginia was the largest city in Virginia and the largest costal city in North America between New York and Charleston, South Carolina. Norfolk had a population of approximately 6,250, the eighth largest city in America and twice the size of Savannah, Georgia.[5] Its location only a few miles from Williamsburg, the colonial capitol of Virginia, and near the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay amplified the city’s strategic political, military, and economic value. As a trading and economic center, Norfolk represented the commercial interests of the ruling elite and therefore had a large Loyalist population with a substantial number of Scottish merchants, whose presence often irritated the planter-dominated Virginia society.[6] The Scottish merchant class tended to remain loyal to the British Crown based on the close ties between commercial and political interests in the mercantile system.[7] Controlling the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay facilitated access to over forty percent of the commerce from the thirteen colonies transiting to Great Britain.[8] Numerous rivers provided water access to the lower portions of Virginia. A large Loyalist-dominated port city, with the capability of hosting a British fleet, in a key strategic location posed a significant threat to the rebel governments of both Virginia and North Carolina and to the Continental Congress.[9]

Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay Region

A shadow government formed in Virginia during 1774 supporting rebel interests; it led directly to provincial military forces challenging the authority of John Murray, Lord Dunmore, the Royal Virginia Governor. It was clear to Dunmore, in the spring of 1775, that the Chesapeake Bay would prove essential to maintaining control of Virginia. As part of his plan to defend the crown’s interests in Virginia, Dunmore sought the support of the British North American Squadron under command of Adm. Samuel Graves. He requested British naval support and emphasized the value of maritime operations in the numerous tidal rivers that extended into Virginia from the Bay. These rivers provided water access via relatively deep and navigable channels that allowed powerful ocean-going warships of frigate class, possessing up to forty-four guns, access deep into the colony and throughout portions of Chesapeake Bay. His request emphasized the value of controlling Virginia’s waterways and preventing contraband and illegal trade in arms and ammunition to supply the rebels. Dunmore believed a large man-of-war in Virginia waters, “would strike Awe over the whole Country.”[10] Unfortunately for Dunmore, with all the British colonial governors under siege, Admiral Graves had a limited number of ships available and some that did arrive carried less cannon than originally designed to mount.[11] Graves reported that “His Majesty’s Ship Liverpool and the Kingsfisher, Otter, Tamer, Raven and Cruizer Sloops are at Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. The St Lawrence Schooner is at St Augustine.”[12] The dispersal of British naval power throughout the southern colonies made it difficult to mass or concentrate available resources to support Lord Dunmore or any other distressed colonial governor. The size and scope of the rebellion facing the British military and civil leaders in 1775 exceeded their immediate ability to address. They failed to heed the warnings of those who understood the potential magnitude of the developing crisis.[13] The inability to hold the strategic Chesapeake Bay region early in the Revolution would haunt the British in the future when they attempted to reestablish the King’s authority there.

Importance of the Chesapeake Bay

During the colonial era, both the northern and southern portions of the Chesapeake Bay contributed to the commercial importance of the region. By 1775, the northern portion so the Chesapeake Bay produced significantly more food stuffs for export than the southern portion. Records from the Annapolis District for December 1774 through July 1775 reflect the sailing of 146 ships bound for overseas ports, primarily to Europe and the West Indies. Only six of these vessels carried tobacco; wheat had become king in the upper Chesapeake. Records from the southern portion of the bay, from the James River District for December 1774 to September 1775, reflect 64 overseas departures, sailing primarily to Scotland, all carrying tobacco. The actual number of shipments was likely much higher than reflected in the official records because smuggling was common.[14] The Continental Congress understood the importance of Chesapeake Bay commerce and took steps to interdict loyalist trade as early as December 2, 1775.[15] The bay was critical because it provided access via water to Virginia, Maryland, Delaware and Pennsylvania. At the time of the American Revolution these states collectively represented forty percent of the population of the new United States[16] and Virginia alone accounted for forty percent of the trade from the thirteen colonies with Great Britain.[17]

Virginia’s Revolutionary Era Population

During the revolution, Virginia was the most populous state in the new nation. The population was disbursed and spread relatively evenly across the state resulting in no large cities other than Norfolk.[18] There was no formal census of the United States until 1790, but analysis derived from available records indicates Virginia had a white population of about 400,000 and a black slave population of about 200,000 at the beginning of the revolution, representing twenty percent of the population of the new United States.[19] The Continental Congress used the 400,000 number to assign recruiting quotas to Virginia for the Continental army in 1776.[20] The first American governor of Virginia, Patrick Henry, corroborated these contemporary population estimates in a letter dated January 14, 1779 addressed to Bernardo Galvez, Spanish Governor of Louisiana, when he stated Virginia’s population was “six hundred thousand of all ages.”[21]

The City of Norfolk had a population of 6,250 in 1775. After the destruction of Norfolk, the largest cities in Virginia were Fredericksburg and Alexandria, both with populations of about 3,000.[22] After Norfolk’s destruction, the absence of a key population center required any occupying force to control broad expanses of territory, which subsequently necessitated a large occupying land force to control the population of Virginia. While a small raiding force could terrorize the population and destroy commerce, this type of force could not seize and hold terrain or control the population.

Virginia had a relatively well-developed county government structure when compared to other less politically mature states, which allowed for effective governance and communication with the citizenry.[23] The failure of the British government to quickly suppress the rebel force in Virginia allowed the rebels to control the local government structures resulting in those with strong Loyalist sentiments to moderate their enthusiasm and wait for strong and sustained British military presence before rising. The lack of initial Loyalist success in Virginia “. . . convinced the weak-hearted to remain neutral, or acquiesce in support of the rebels.”[24] Dunmore’s November 7, 1775 decree to free “all indented servants Negroes or others (appertaining to Rebels) … that are able and willing to bear Arms,”[25] also alienated many former loyal supporters of the King and his royal governor,[26] as well as raising fears of the committees of safety in other southern colonies.[27] Following the destruction of Norfolk, the absence of serious British military activity for three years allowed Virginia to become the breadbasket of the revolution. Virginia possessed a surge capacity to support the American war efforts and supplied between 3,000 and 6,200 troops to the Continental army throughout the war as well as Whig militia and critical economic, political, and military leadership contributions. The only other state to achieve this type of success in supplying manpower to the Continental army was Massachusetts.[28] The destruction of Norfolk and the lack of large population centers prevented British forces from rallying Loyalist support and controlling the state without a major commitment of forces.

Howe and North Carolina’s Interest and Linkage to Norfolk

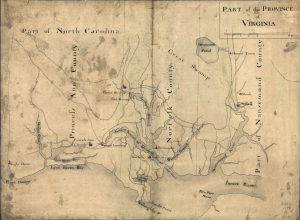

The provisional government of North Carolina viewed the Tidewater region of Virginia as an avenue of approach into the Albemarle region of North Carolina. A Loyalist stronghold in the Norfolk area provided a base for future operations into northeast North Carolina, a region known for some Loyalist sentiment. As Lord Dunmore worked, during the summer and fall of 1775, to build a military capacity to challenge the rebel forces in the lower Chesapeake Bay, North Carolina repositioned forces north and activated militia units adjacent to Virginia in Edenton, Pasquotank, and Currituck Counties to reinforce the Virginians and challenge Dunmore’s assembled forces. The Continental Congress ordered the two battalions of troops raised by North Carolina into Continental service on November 28, 1775. This positioned North Carolina Continental troops and North Carolina Militia, under the command of Robert Howe, to quickly respond to the military actions of Lord Dunmore in Tidewater Virginia.[29]

Virginia Military Actions and Great Bridge

After successfully repulsing a British assault on Hampton, Virginia, the state’s provisional government repositioned Virginia’s 2nd Regiment, under command of William Woodford, to the south side of the James River and ultimately to Great Bridge to prevent Dunmore’s force from controlling that strategic location and advancing into the Albemarle region of North Carolina.[30] Norfolk was located strategically on the banks of the Elizabeth River in relation to Princess Anne, Norfolk and Nansemond Counties of Virginia and the Albemarle region of North Carolina. The Great Bridge provided the only land access from the north to the Albemarle region, east of the Great Dismal Swamp. Possession of Great Bridge controlled the north-south traffic between Virginia’s Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties and North Carolina’s Albemarle region.

Based on his success in defeating the Princess Anne County Militia in the skirmish at Kemps Landing on November 15, 1775, Dunmore felt confident his disciplined regulars, recently reinforced by a detachment of sixty men of the 14th Regiment from St. Augustine, East Florida,[31] and local militia could drive the rebel defenders from the south end of the Great Bridge, opening the road into North Carolina before the North Carolina troops could arrive to reinforce them. Dunmore underestimated the strength and determination of the entrenched enemy. Great Bridge was a British bloodbath. The elevated causeway over marshy terrain required the British regulars to advance on a narrow front that exposed them to direct frontal and flanking fire from the muskets and rifles of the defenders, which decimated the regulars leading the attack. Immediately after the battle, Col. William Woodford, the rebel commander, reported British casualties as, Captain Fordyce and twelve privates killed with Lieutenant Batut and seventeen privates wounded.[32] Another contemporary account reported Dunmore’s force left thirty-one killed and wounded on the battlefield in the hands of the rebels.[33] The day after the battle, Woodford made a more detailed inspection the battlefield and indicated British losses were higher than first reported, but he provided no numbers. Reports circulated indicating as many as one hundred British casualties, but these were likely overstated. More recent estimates place the British casualties at sixty-one killed and wounded with one rebel wounded producing casualty figures more consistent with Woodford’s initial reports and estimates.[34] Regardless of the numbers lost, regulars killed and wounded represented a sizable portion of Dunmore’s regular troops, the backbone of his military capability.[35] The defeat of the regulars shattered the confidence of Dunmore’s Loyalist forces, and emboldened the Virginia rebels who were subsequently reinforced by Howe’s North Carolina Continentals just three days after Dunmore’s assault failed to dislodge Woodford’s troops.[36]

Norfolk Occupation and Howe’s Assumption to Command

After the resounding Great Bridge victory, the rebels possessed the initiative and proceeded north in pursuit of Dunmore’s depleted and demoralized force. Dunmore was in trouble, and he knew it. With insufficient forces to hold the loyalist-dominated city of Norfolk, Dunmore moved his command, the Virginia Royal Government, and desperate Loyalists aboard ships in the adjacent Elizabeth River. After discussions between Colonels Howe and Woodford, and with consent of Virginia’s provisional government, on December 14, 1775, Howe assumed command of the combined North Carolina-Virginia military force as the senior Continental officer present.[37]

The consolidated command facilitated unity of effort and command, and enabled Howe to effectively negotiate from a position of strength.[38] Conversely, Dunmore’s troops and the Loyalist refugees struggled to subsist aboard cramped ships that floated, at times, only yards from the Norfolk waterfront. Just obtaining fresh water became difficult as the troops occupying Norfolk challenged all attempts to forage for food, water and other necessities. Dunmore made attempts to exchange prisoners and acquire supplies from the provision-rich Tidewater and Albemarle regions, but Howe resisted and began to assess his strategic options.[39]

Assessment of the Situation in Norfolk

Howe’s combined North Carolina-Virginia force outnumbered Dunmore’s military strength, yet neither side fielded the number of troops needed to occupy and effectively control Norfolk, Virginia’s largest city. Both Howe and Dunmore estimated a requirement of 5,000 troops to hold Norfolk; Howe’s entire force numbered 1,275 men on December 17, 1775.[40] The stalemate around Norfolk presented an unpleasant environment for both Dunmore’s Loyalists aboard ship and Howe’s men ashore. Whig Col. Scott described Norfolk as a horrible cold,

| Unit | Strength |

| Virginia 2nd Regiment | 350 |

| Virginia Minute Battalion | 165 |

| Detachment of Virginia 1st Regiment | 172 |

| North Carolina 2nd Regiment | 438 |

| North Carolina Volunteers | 150 |

| Total | 1275 |

Table 1: North Carolina & Virginia Troop Strength at Norfolk, December 1775

damp, miserable place where men stood duty for forty-eight hours without relief.[41] Frustration aboard the British ships flared as the cramped quarters and limited provisions took their toll.[42] Howe refused to allow those aboard to go ashore or purchase food. The situation worsened as the rebels occupying Norfolk made their presence visible to those aboard ship. Waving and hollering devolved into obscene gesturing, then, the ultimate insult, firing on the British warships.[43] As early as December 14 the journal of HMS Otter reported shots fired at the warship by troops occupying Norfolk.[44] An ensign aboard the Otter, knowing that there were insufficient British forces to prevent the occupation of Norfolk by the rebels, went ashore under a flag of truce carrying a message from Dunmore demanding Colonel Howe stop firing on the British warships followed by the threat that, “if another shot was fired at the Otter, they must expect the town to be knocked about their ears.”[45]

Capt. Matthew Squires, commanding the Otter, had previously witnessed the same type of rebel behavior he experienced along the waterfront at Norfolk. The ship’s journal or log recorded a similar experience a few months earlier when the Otter supported General Howe’s forces under siege by the rebels in Boston. An entry for Thursday, May 4, 1775 reads, “Off Castle William Island [Boston Harbor] at 11 the Rebels came down the Point & fired several times at the Ship & our boats as they passd on which we discharged some Musquets at them but they taking no notice of it we fired seven Swivels & dispersed them.”[46] Captain Squires shared the view of his admiral when using force to suppress the rebels to modify their belligerent behavior. Upon learning of the events of April 19, 1775, at Lexington and Concord, Adm. Samuel Graves, the British North American squadron commander, recorded his thoughts on a course of action to punish the rebels, “It was indeed the Admirals opinion that we ought to act hostiley from this time forward by burning & laying waste the whole country, & his inclination and intentions were to strain every nerve for the public Service” He also proposed, “… the burning of Charles town and Roxbury, and the seizing of the Heights of Roxbury and Bunkers Hill …”[47] No doubt, the opinions and intent of the Admiral Graves influenced the actions of the officers commanding his warships assigned to support the various royal governors as they attempted to regain control of their respective colonies.

Capt. Henry Bellew, in command of the twenty-eight-gun frigate HMS Liverpool, arrived in Virginia to support Lord Dunmore and his Loyalist followers on December 21 with 400 marines and the store ship Maria. Captain Bellew warned the rebels they would use force if parties were not permitted to come ashore to purchase supplies from the locals. By Christmas Day the situation continued deteriorating, and the rebels received timely reinforcements in the form of 180 men of a minute battalion to help with security responsibilities.[48] The arrival of these men, on Christmas Day, likely raised the spirits of the men who were standing duty for two days at a time without relief. On December 30, Captain Bellew issued an ominous warning: “As I hold it incompatible with the honour of my commission to suffer men, in arms against their Sovereign and the Laws, to appear before His Majesty’s ships, I desire you will cause your sentinels, in the town of Norfolk to avoid being seen, that women and children may not feel the effects of their audacity; and it would not be imprudent if both were to leave the town.”[49] Howe, however, remained impervious to the British attempts and held steadfast in his resistance to all British intimidation and threats.[50]

While Colonel Howe took a hard line on dealing with the British military leaders and Lord Dunmore aboard ship, he and Colonel Woodford were more understanding of the plight of more recent immigrants. A group of Scottish Highlanders, apparently bound for North Carolina, found themselves stranded in Norfolk during the rebel occupation. Woodford requested guidance from the Virginia Convention on how to deal with these individuals and received instructions from the Convention to “… take the distressed Highlanders with their families under his protection, permit them to pass by land unmolested to Carolina and supply them with such provisions as they may be in immediate want of.”[51]

Destruction of Norfolk

The assembled British fleet unleashed a barrage of cannon fire on Norfolk and the rebels at about 3:00 p.m. on New Year’s Day of 1776. In all, ships mounting an estimated one hundred naval cannons participated in the firing that continued through 2 a.m. on January 2. Dunmore also sent ashore landing parties to forage through the warehouses and burn houses and buildings near the waterfront, but the rebels repulsed most of these landing parties.[52] Firing a variety of ammunition into wooden structures, one would envision massive destruction near the waterfront followed by fires, fanned by winds off the water that consumed adjacent structures. Legend has it that Norfolk disappeared as Dunmore took out his frustrations on the only city capable of sustaining a substantial British military presence in the lower Chesapeake Bay. The facts are quite different, however, in terms of the amount of damage inflicted in this January 1, 1776 cannonade.

The bombardment provided an opportunity for the Rebel troops to join in the destruction of the principally Loyalist city and the associated private property of its citizens. The Americans, Patriots from North Carolina and Virginia, not Lord Dunmore and his fleet, destroyed Norfolk to deny its use to the British. Howe realized the American rebels did not have sufficient forces to hold the city and prevent its use by the British in the future. The American Patriots finished what Lord Dunmore started and in doing so, destroyed the only large and capable military port in the southern Chesapeake Bay.

Virginia’s Formal Assessment of the Destruction of Norfolk

In 1777, the State of Virginia appointed commissioners to examine the details of the destruction, with a mission to “ascertain the Losses occasioned to individuals by the burning of Norfolk and Portsmouth, in the year 1776.” The committee, including Richard Kello, Joseph Prentis, Daniel Fisher and Robert Andrews, conducted the assessment of damages between September 8 and October 10, 1777. Other committee members conducted a similar assessment of the cities Portsmouth and Suffolk. The commissioners determined Dunmore’s bombardment of the city only destroyed nineteen structures valued at 1,616 pounds sterling.[53] While the bombardment may have been a sight to behold, and terrorized those in the vicinity, it did not result in the destruction of Norfolk. The tables presented here show the losses attributed to the British forces and to the American or Patriot forces, indicating the losses in Norfolk only; the committee found the losses in Portsmouth and Suffolk were much less extensive.

| Date of Destruction | # Houses | House Value * | Personal Property Value * |

| November 30, 1775 | 32 | 1,948 | 180 |

| January 1, 1776 | 19 | 1,616 | 1,305 |

| January 21, 1776 | 3 | 114 | |

| Totals | 54 | 3,678 | 1,485 |

*Value in Pounds Sterling

Table 2, Losses in the City of Norfolk attributed to the British forces

| Date of Destruction & Responsible Party | # Houses | House Value * | Personal property Value * |

| State troops, Before January 15, 1776 | 863 | 110,807 | 8,085 |

| Convention (Virginia government) ordered February 1776 | 416 | 49,663 | 2,707 |

| Totals | 1,279 | 160,470 | 10,792 |

*Value in Pounds Sterling

Table 3, Losses in the City of Norfolk attributed to the American forces

These tables reflect the findings of the commission that American Patriot or Rebel forces destroyed 1,279 of the 1,333 homes or structures, or ninety-six percent. The actions of British and Loyalist forces, under the command of the Royal Governor, Lord Dunmore, destroyed only 54 structures.

The Impact of Norfolk’s Destruction

The systematic and deliberate destruction of Norfolk was one of the more important and far-reaching strategic military decisions made by the southern provisional Rebel governments early in the American Revolution. The provisional governments of North Carolina and Virginia understood the importance of denying the use of the most capable port city between New York and Charleston to the British. When the British returned to the Chesapeake Bay region in 1779 and again in 1780 and 1781, the lack of a capable port and port city resulted in Generals Alexander Leslie, Benedict Arnold and William Phillips ultimately establishing their base of operations in Portsmouth, Virginia. Portsmouth retained some infrastructure after the destruction of Norfolk but proved a poor location with low-lying terrain and an inadequate channel depth to support ships of the line.[54] This led the British to Yorktown, after considering other basing options,[55] where Lord Cornwallis eventually surrendered 8,000 British forces on October 19, 1781.

Had Norfolk remained a functional port city, the British could have used the location to rally and consolidate Loyalist support, build local Loyalist militia units and counter the rebel militia. This is exactly what Benedict Arnold tried to do in early 1781 when the British committed land forces to the region, but it was too little too late. Upon his arrival in Virginia in 1781, Lord Cornwallis made a similar analysis of the importance of controlling the Chesapeake Bay, the area’s commerce and the population. He appropriately concluded that Virginia’s navigable rivers made the state vulnerable to the mobility and sustainability of a land force with adequate maritime support. He stated in a letter to his superior, Gen. Henry Clinton, on August 20, 1781, “… that if we have the force to accomplish it the reduction of the province would be of great advantage to England on account of the value of its trade to us, the blow that it would be to the rebels, and as it would contribute to the reduction and quiet of the Carolinas.”[56]

The local population lived under rebel control for years and the raiding strategy implemented in 1779 proved to the locals that the British did not intend to remain in force and instead only punish those who supported the Whig-controlled government. When General Leslie remained in the area for only a month during 1780, the locals again came under rebel control upon his departure. The local population viewed Benedict Arnold’s arrival in late 1780 as one more temporary British occupation. Local, politically moderate leaders remained skeptical of British seriousness to remain in the region.[57] As the British attempted to regain control of Virginia in 1781, by committing large numbers of land forces, the true strategic value of Norfolk emerged.

The British occupation of the Tidewater region in 1780-1781 reignited an ugly phase of the local civil war that festered in the area as the British evacuated Portsmouth in favor of a base at Yorktown. Gen. Charles O’Hara, Lord Cornwallis’s second in command and the man who formally surrendered the British forces at Yorktown, had the responsibility to close the base at Portsmouth. As he removed the remaining supplies and soldiers from Portsmouth he decided to bring numerous local Loyalists to Yorktown as well. He wrote to Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, “It is unavoidable, I am brining you all the inhabitants of Princess Anne and Norfolk Counties. What an unfortunate scrap they are in!”[58]

Had the city of Norfolk remained functional and avoided complete destruction in 1776, the history of the revolution in the Chesapeake Bay would have been very different. Had the Royal Government possessed the capability to physically protect Norfolk, the loyal population would have remained in place, and with the infrastructure largely intact, provided a base for sustaining the British maritime and land forces. A base near the mouth of Chesapeake Bay would have allowed for more aggressive maritime patrolling and would have assisted in closing the bay as an effective shipping route. The decisive actions of Col. Robert Howe and the North Carolina and Virginia provisional governments in authorizing the destruction of Norfolk were bold and crucial. These men deliberately destroyed the second largest American city south of Philadelphia and the eighth largest city in North America. Had they waivered in this decision, the history of the war in the south would have been quite different.

Without a persistent British maritime and land presence in the lower Chesapeake Bay, the Rebels just waited to act until the maritime and land forces departed the area. As one early twentieth century Virginia researcher and historian noted, the British navy “… enabled them to dominate the sea, and the counties lying on navigable waters were thus kept in frequent alarm.” But the, “British had no foothold on Virginia soil.”[59] While there was no way for the Whig government of Virginia to prevent the more capable British navy from actively patrolling Chesapeake Bay with limited naval vessels, and prior to the commitment of significant numbers of British land forces during 1781, the rebels devised a method to help safeguard commerce and provide a warning to mariners of active British maritime or privateer presence in the bay. Virginia established a very simple system to alert vessels attempting to enter the Chesapeake Bay if British ships were on patrol there. If the bay was clear, officials hoisted a large red and white striped flag on a fifty-foot-high pole mounted on the sand dunes at Cape Henry. At night, a lantern served as a signal. When the British navy or privateers closed the lower Chesapeake Bay to shipping, cargo traveled by wagon to South Quay, a port that could handle ships up to 200 tons, located southwest of Franklin, Virginia, in Southampton County. South Quay, located along the Blackwater River, allows access into the Chowan River reaching into the Albemarle Sound in North Carolina, at Edenton. This route provided access to the Atlantic Ocean through the Outer Banks at Ocracoke Inlet. This route into southeastern North Carolina validated North Carolina’s concerns expressed early in the revolution that the two regions, Tidewater Virginia and Albemarle North Carolina, were accessible to forces occupying Norfolk. The destruction of Norfolk served both the States of North Carolina and Virginia preventing the British from retaining control of the region.[60] One may correctly conclude that the seeds of the British defeat at Yorktown in October 1781 took root with the destruction of Norfolk in early 1776.

[1] Charles E. Bennett and Donald R Lennon, A Quest for Glory: Major General Robert Howe and the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 28; Robert Howe was appointed colonel of the 2nd North Carolina Regiment by the North Carolina Provincial Congress on September 1, 1775. The Continental Congress took both the 1st and 2nd North Carolina regiments into Continental service in late November 1775. When Howe assumed command of the combined North Carolina-Virginia forces he did so as a Continental officer.

[2] Minutes of the Virginia Convention December 01, 1775, in William Laurence Saunders, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina. (Raleigh NC: P.M. Hale, 1886), 10:396, http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/volumes/volume_10, accessed June 18, 2017.

[3]James E. Heath, Journal and Reports of the Commissioners Appointed by the Act of 1777, to ascertain the Losses occasioned to individuals by the burning of Norfolk and Portsmouth, in the year 1776 (Richmond, VA: House of Delegates, Auditor, Richmond: Virginia General Assembly, 1836).

[4] Paul H. Smith, Loyalists and Redcoats: A Study in British Revolutionary Policy (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1964), 82-109; and John E. Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 1775-1783 (Charlottesville, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1988), 204-210.

[5] Carl Bridenbaugh, Cities in Revolt: Urban Life in America 1743-1776 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1955), 217.

[6] Ernest McNeill Eller, ed., Chesapeake Bay in the American Revolution (Centerville, MD: Tidewater Publishers, 1981), 312; and Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 205.

[7] Bennett and Lennon, A Quest for Glory, 31.

[8] Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 26.

[9] Worthington C. Ford, et al., ed., Journals of the Continental Congress (Washington, DC, 1904-37), December 2, 1775, 3:395-6, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(jc00362)), accessed September 23, 2017.

[10] Lord Dunmore to Samuel Graves, May 1, 1775, in William B. Clark, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington, DC: Naval History Division, Deptment of the Navy, 1964), 1:257-8, http://www.ibiblio.org/anrs/docs/E/E3/ndar_v01.pdf, accessed June 29, 2017.

[11] Thomas Ludwell Lee to Richard Henry Lee, December 23, 1775, in Clark, Naval Documents, 3:219, http://www.ibiblio.org/anrs/docs/E/E3/ndar_v03.pdf, accessed July 4, 2017.

[12] Vice Admiral Samuel Graves to Capt. Andrew Barkley, December 26, 1775, in Ibid., 3:256.

[13] John Ferling, Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 29.

[14] Eller, Chesapeake Bay, 14, 16.

[15] Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, December 2, 1775, 3:395-6, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(jc00362)), accessed September 23, 2017.

[16] Peter Smith, American Population Before the Federal Census of 1790 (Glouchester, MA: Columbia University Press 1966), 8-8, 141; Robert K. Wright, The Continental Army (Washington, DC: Center for Military History 1983), 94.

[17] Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 26.

[18] Smith, American Population, 141; Wright, The Continental Army, 94; Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 23-27; and Emily J. Salmon and Edward D.C. Campbell, Jr., eds., Hornbook of Virginia History, (Richmond,VA: The Library of Virginia, 1994), 92.

[19] Smith, American Population, 6-8, 141.

[20] Wright, The Continental Army, 94.

[21] Henry to Galvez, January 14, 1779, in Ian Saberton, ed., Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War, (Uckfield, England: The Naval & Military Press Ltd, 2010), 3:300.

[22] Eller, Chesapeake Bay, 314-15.

[23] J. T McAllister, Virginia Militia in the Revolutionary War (Hot Springs, VA: McAllister Publishing Co., 1913), introduction, http://lib.jrshelby.com/mcallister-harris.pdf, accessed July 4, 2017. “Of the present 69 counties of the former Eastern District, [present State of Virginia] 58 were already in existence at the outbreak of the Revolution in 1775.” Virginia’s government was much closer to the people of the sate when compared to a politically less mature state. For example, Pennsylvania consisted of only eleven counties in 1775, yet Pennsylvania possessed the third largest population of the original thirteen states behind Virginia and Massachusetts. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1681-1776: The Quaker Province, Pennsylvania on the Eve of the Revolution, http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/portal/communities/pa-history/1681-1776.html, accessed August 20, 2017; Salmon and Campbell, Hornbook, 159.

[24] Eric Robson, The American Revolution: In its Political and Military Aspects, 1763-1783 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1966), 118.

[25] H. S. Parsons, “Contemporary English Accounts of the Destruction of Norfolk in 1776,” The William and Mary Quarterly, 13, no. 4 (1933): 219-224.

[26] Committee to draw up a Declaration in answer to Lord Dunmore’ s Proclamation of November 7, December 8, 1775, in Peter Force ed., American Archives, Documents of the American Revolutionary Period, 1774-1776 (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1844), ser. 4, 4:79, http://amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A87007, accessed June 27, 2017.

[27] Minutes of the South Carolina Council of Safety, December 20, 1775, in Clark, Naval Documents, 3:190.

[28] Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 131.

[29] Minutes of the Virginia Convention December 01, 1775, in Saunders, Colonial and State Records, 10:341; Minutes of the Continental Congress [Extracts] November 24, 1775 – November 26, 1775, in Saunders, Colonial and State Records, 10:338-339; Bennett and Lennon, A Quest for Glory, 29; and Virginia Gazette (Purdie), November 10, 1775, http://research.history.org/DigitalLibrary/va-gazettes/VGSinglePage.cfm?IssueIDNo=75.P.79, accessed June 30, 2017.

[30] Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 63.

[31] Alexander Ross to Captain Stanton, October 4, 1775, in Force, American Archives, ser. 4, 4:335, http://amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A91713, accessed July 1, 2017.

[32] William Woodford to the President of the Virginia Revolutionary Convention, December 9, 1775, Revolutionary Government, Papers of the Fourth Virginia Convention, Record Group 2, Accession 30003, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA; William Woodford to Edmund Pendleton, Virginia Gazette (Pinckney), December 13, 1775, http://research.history.org/DigitalLibrary/va-gazettes/VGSinglePage.cfm?IssueIDNo=75.Pi.61, accessed June 30, 2017.

[33] Full account of the battle at the Great Bridge, in Force, American Archives, ser. 4, 4:228-9, http://amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A105647, accessed 20 June 2017.

[34] Mark M. Boatner, “Great Bridge Va.,” Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1994), 447-448.

[35] “Correspondant,” Virginia Gazette (Pinckney), December 13, 1775.

[36] Bennett and Lennon, A Quest for Glory, 30.

[37] Colonel Howe to the President of the Virginia Convention, 15 Dec 1775, in Force, American Archives, ser. 4, 4:278, accessed 1 July 2017; Colonel Woodford to Virginia Convention, 15 Dec 1775, vol. 4, 278-9, http://amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A101159, accessed July 1, 2017.

[38] Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 1, Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States, (Washington, D.C.: 2017). Howe understood the importance of dealing with the Royal Governor with a single military voice guided by the political leadership of North Carolina and Virginia.

[39] Bennett and Lennon, A Quest for Glory, 30-1.

[40] Louis Van L. Naisawald, “Robert Howe’s Operations in Virginia 1775-1776,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 60, no. 3 (1952): 438; Return of the Forces under command of Colonel Howe, at Norfolk, December 17, 1775, in Force, American Archives, ser. 4, 4:278-9, http://amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A95607, accessed July 1, 2017; Bennett and Lennon, A Quest for Glory, 30-32; and Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 68.

[41] Colonel Scott to Captain Southall, in Force, American Archives, ser. 4, 4:292, http://amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A84260, accessed July 1, 2017; Naisawald, “Robert Howe’s Operations,” 438.

[42] Minutes of the Virginia Convention, January 2, 1776, in Saunders, Colonial and State Records, 10:380-1.

[43] Bennett and Lennon, A Quest for Glory, 31-2.

[44] Journal of his Majesty’s Sloop Otter, Matthew Squires Commanding, December, 14, 1775, in Clark, ed., Naval Documents, 3:197.

[45] Letter from a Midshipman Onboard H.M. Sloop Otter, December, 14, 1775, in ibid., 3:103.

[46] Journal of his Majesty’s Sloop Otter, Matthew Squires Commanding, Thursday, May 4, 1775, in ibid., 1:278.

[47] Narrative of Vice Admiral Graves, Boston, April 19, 1775, in ibid., 1:193.

[48] Robert Howe to Edmund Pendleton, in Saunders, Colonial and State Records, 10:365.

[49] Henry Bellew to Howe, in ibid., 10:372.

[50] Howe to Bellew, in ibid., 10:372.

[51] Minutes of the Virginia Convention, December 14, 1775, in ibid., 10:346.

[52] Parsons, “Contemporary English Accounts,” 222.

[53] Heath, Journal and Reports, 16.

[54] Clinton to Cornwallis, July 8, 1781, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 5:140; and 3:3.

[55] Clinton to Cornwallis, July 11, 1781, in ibid., 5:139; and Cornwallis to Graves, July 26, 1781, in ibid., 4: 41.

[56] Cornwallis to Clinton, August 20, 1781, in ibid., 6:24.

[57] Johann Ewald, Diary of the American War, A Hessian Journal, Joseph P.Tustin ed. and trans. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 276-7.

[58] O’Hara to Cornwallis, August 15, 1781, in Saberton, ed., Cornwallis Papers, 6:51.

[59] McAllister, Virginia Militia, 1.

[60] Eller, Chesapeake Bay, 310-20.

Recent Articles

That Audacious Paper: Jonathan Lind and Thomas Hutchinson Answer the Declaration of Independence

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Recent Comments

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Thank you Eric! I should say that I have enjoyed your work...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...