Gen. George Washington’s well-crafted November 10, 1775 letter to Col. William Woodford contains some timeless pearls of military wisdom, guidance, and advice.[1] Washington’s instructive response to an earlier letter from Woodford reveals a set of basic leadership principles that remain in official United States Army doctrine to this day. This enduring leadership lesson leads one to an examination of Woodford’s actions to reveal if he heeded Washington’s recommendations and council. Assessment of Woodford’s leadership actions during the first months of the Virginia Campaign of 1775-76 suggest he did, and he apparently benefitted because of it.

While Woodford’s letter to Washington initiating Washington’s response has yet to be located, Washington’s answers provide some specific guidance allowing us to understand the nature of the questions posed by Woodford and appreciate the mentoring advice Washington offered. Today’s U.S. Army leadership doctrinal guidance emphasizes adhering to Army values in ethical decision making, instilling discipline, and building trust while balancing the needs of subordinates with mission requirements.[2] Elements of this broad approach are clearly evident in Washington’s guidance as well as in Woodford’s actions. This should not be a surprise, as contemporary Army leadership doctrine clearly asserts that today’s “army ethic has its origins in the philosophical heritage, theological, and cultural traditions, and the historical legacy that frame our Nation.”[3] Washington’s letter to Woodford validates the Army’s assertion.

Examining Washington’s letter is enlightening for a number of reasons; it exemplifies the commander-in-chief’s innate ability to counsel, coach and mentor his subordinate commanders. Washington specifically noted that he “highly approved” of Woodford’s appointment to command. That must have been a confidence builder for Woodford. Washington also acknowledged concerns over “inexperience.” Woodford likely addressed the inexperience of both officers and men he witnessed as Virginia’s first units began to form at Williamsburg. Given the twelve years between the end of the French and Indian War and the American Revolution, Woodford was dealing with many volunteers with no combat or military experience, including his company commanders and company officers.[4] Washington’s advice for overcoming inexperience was nothing more than “practice.” Concerning relations with officers he advised, “be easy and condescending . . . but not too familiar.” Washington coached Woodford through the basics necessary for successful command.

Washington stressed obedience and “punctuality” in following orders and guidance. He recommended strict discipline but tempered this guidance by stating “require nothing unreasonable of your officers and men.” He advised, “reward and punish each man according to his merit.” He further advised Woodford to hear their complaints but discourage them unless they were well founded to prevent “frivolous” complaining. He recommended avoiding vice and to impress upon everyone the “importance of the cause” upon which they were embarking. Washington’s “best advice” to Woodford was the very foundation of today’s Army ethic; he advocated “a set of moral principles, values, beliefs, and laws that guide the Army profession and create a culture of trust.”[5]

Maintaining good order and military discipline of soldiers was clearly a focus of Woodford’s letter to Washington. Volunteer companies of Patriots descended on Williamsburg during the summer of 1775 and refused to follow instructions of anyone other than their individual company commanders, leading some citizens to fear anarchy. Woodford was aware this type of behavior and clearly sought Washington’s thoughts on how to approach his new military leadership role.[6]

Washington’s counsel gave the essence of leadership, “purpose, direction, and motivation,” to his trusted subordinate.[7] Addressing tactical issues, he advised “guarding against surprise,” including posting guards, providing front, rear and flank guards during a march, and practicing good security during encampments. He recommended sound security measures “whether you expect an enemy or not.” He suggested clear concise orders, and to keep copies of these orders to avoid mistakes.

Concerning the “manual exercise,” the drill for handling firearms, Washington recommended the use of Humphrey Bland’s A Treatise of Military Discipline “(the new addition)” as a reference for ensuring military discipline and organization. On tactical matters, unit employment and training of military forces he recommended texts known to be in Washington’s personal library, “An Essay on the Art of War; Instructions for Officers, the Partisan; Young; and others.”[8] Washington used his letter to persuade Woodford to develop his own expertise, through what today would be called professional self-development. Washington’s counsel guided Woodford’s preparation for a daunting task.

The Third Virginia Convention selected William Woodford to command the 2nd Virginia Regiment and appointed him effective August 17, 1775. Woodford was not the first choice to command one of Virginia’s first two regiments created to drive the royal governor, John Murray, Lord Dunmore, from the colony. Earlier, the Convention voted to elect Thomas Nelson Jr. as the commander of the 2nd Virginia. Nelson declined, accepting instead an appointment to represent Virginia at the Second Continental Congress, leading to Woodford’s appointment.[9]

Patrick Henry was appointed to command Virginia’s 1st Regiment and serve as the commander-in-chief of Virginias forces. When it came time to send Virginia’s newly formed military units into combat Henry was not viewed as the most capable military field-leader available. Henry’s passion and commitment to the cause are well known, but Woodford was the warrior. Woodford, with combat experience in the French and Indian War, was the first choice to lead men to challenge British colonial rule.[10] The Virginia Convention, like Washington, recognized Woodford’s potential and “highly approved” of his potential for success on the field of battle.

Woodford had not yet led any of his newly authorized men into combat when he drafted his letter on September 18, 1775. Only a few men in hastily organized units were actually assembling at Williamsburg at that time and these companies were poorly prepared for war. But Woodford understood that more units would arrive and he needed to train these men and units to build effective military capacity quickly. Enough companies arrived by September 27, 1775 to begin serious training and organization and regularly record proceedings in an orderly book.[11]

Woodford first led Patriot men into combat in late October 1775 at Hampton, Virginia. Reinforcing the local militia positioned there, Woodford led an all-night march with elements of the 2nd Virginia Regiment and Culpeper Battalion from Williamsburg to Hampton, arriving just in time to repulse a British amphibious attack into Hampton’s harbor and inflicting the first casualties on British navy and Loyalist forces.[12]

Woodford and Henry’s regiments continued forming in Williamsburg at College Camp as the action at Hampton unfolded. College Camp was appropriately named because it was located adjacent to the campus of William and Mary. Prior to the engagement at Hampton, the Virginia Committee of Safety selected Woodford to lead a task force south of the James River to eject British and Loyalist forces from Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties and occupy the City of Norfolk.[13] The crisis at Hampton delayed the move across the James River, with the advance guard crossing on November 7, 1775 and follow-on forces crossing during the next ten days. Woodford closed on Great Bridge on with bulk of his eleven-company task force about December 2, 1775.[14] He was careful to advance deliberately to avoid surprise, as cautioned by Washington.

All indications are Woodford heeded Washington’s recent and pointed guidance on security.[15] For the next week, Woodford established a defensive position at the south end of the Great Bridge causeway. The British units, mostly Loyalist militia, on the north end of the causeway, exchanged fire with Woodford’s men. Woodford maintained a limited offense, initiated raids and probed the defenses, but there was no attempt to cross the causeway. Woodford possessed imprecise intelligence on the numbers and quality of enemy he faced. He acted with caution because his troops were raw and relatively untrained and he was unclear of enemy intentions and capabilities. While Woodford was cautious, Lord Dunmore, the royal governor, was less so. Woodford certainly limited himself to a prudent level of risk.

Woodford heeded Washington’s advice to remain at a high state of readiness in case of a surprise attack. He also prepared strong earthen fortifications to protect his troops. His engineer, Lt. Col. Thomas Bullitt, an experienced veteran of the French and Indian War, constructed earthworks positioned on the front and flank of the advancing British assault element.[16] On the morning of December 9, 1775, elements of the Company of Capt. Richard K. Meade of Woodford’s 2nd Virginia Regiment, led by Lt. Edward Travis, manned the earthwork on the causeway and elements of the Culpeper Minute Battalion occupied earthworks on the left of the Patriot position.

The ill-fated British assault was ordered by Dunmore early that morning. One hundred and twenty members of the British 14th Regiment of Foot led the assault supported by hundreds of loyalist militia. Forced to attack in a tight six-man front on the narrow causeway, the attackers’ lead ranks were pummeled with musket and rifle fire from the earthworks. The regulars of the 14th Regiment suffered 50 percent casualties in a matter of minutes, initially confronted by only the Patriot security forces. Witnessing the devastation inflicted on the advancing British grenadiers and infantrymen Captain Mead remarked, “The scene, when the dead and wounded were bro’t off, was too much; I then saw the horrors of war in perfection, worse than can be imagin’d; 10 and 12 bullets thro’ many; limbs broke in 2 or 3 places; brains turning out. Good God, what a sight! what will satisfy the governor”?[17]

After the fight ended and dead and wounded were removed from the battlefield Lieutenant Colonel Bullitt encouraged Woodford to advance and drive the Loyal forces from the stockade at the north end of the causeway. Once again Woodford followed Washington’s guidance and declined to advance, unsure of Lord Dunmore’s capability to reinforce; he shunned unnecessary risk to “forever keep the necessity of avoiding surprises.”[18] Woodford remained cautious over the next several days for good reason.[19] His line of communications back to Williamsburg, guarded by a few hastily mobilized militia detachments, stretched over seventy-five miles, and Patriot reinforcements were on the way.[20]

Loyalist forces were operating in Woodford’s rear. Loyal partisans destroyed the bridge spanning Deep Creek at Bachelor’s Mill between Suffolk and Great Bridge, leaving his supply wagons and sustainment stranded there. The bridge required rebuilding in order to properly provision the growing number of units assembling at Great Bridge.[21]

Woodford chose to advance on Norfolk before his supply trains reached Great Bridge, but he did so deliberately as evolving intelligence revealed the state of the defenses in front of him. It was nearly twenty miles by land from Great Bridge to Norfolk and Woodford established an intermediate staging base at Kemps Landing, about half way to his objective, garrisoning this strategic location with an entire company. Captain Meade reported on December 18 that he had been on guard duty for six of the last seven nights. Aware of Loyalist sentiments and partisan activity, Woodford could not be overly cautious, again adhering to Washington’s guidance on preparedness.[22]

After entering Norfolk Woodford turned over command of the combined North Carolina-Virginia task force to Colonel Robert Howe because of his seniority, but remained in command of the Virginia forces that made up the bulk of the nearly 1,300 men assembled there.[23] Relations between Howe and Woodford appear to have been cordial.[24] Woodford, ever the humble adherent of Washington’s recommended discipline and organization, settled into his role under Colonel Howe.

Washington’s advice in being “precise” keeping “copies of orders” was another recommendation heeded by Woodford. The initial structure of the 2nd Virginia Regiment included an adjutant but not a secretary. A secretary was included in the structure of the 1st Virginia Regiment. Woodford appealed to the Virginia Committee of Safety and they conceded assigning Thomas Meriweather as a secretary on December 9, 1775. Although assigned on the day of the action at Great Bridge, Meriweather’s appointment no doubt improved administrative actions in keeping the political leadership in Williamsburg apprised of the situation south of the James River.[25] At least somewhat through Washington’s urging, Woodford focused on organization, communication, and discipline; traits and skills at the forefront of Army leadership doctrine to this day.

Modern Army leadership doctrine notes that Washington declared, “discipline is the soul of the Army.”[26] Washington’s recommendations on enforcing discipline were also evident in Woodford’s actions. There are numerous records of appointing officers to serve on courts martial trying violations of military discipline by officers as well as enlisted soldiers.[27]

Lt. Francis Boykins, of Captain Davie’s Company, 1st Virginia Regiment, was acquitted by a court martial presided over by Maj. Alexander Spotswood, of deserting his post. The court acquitted Boykins because his unit lacked adequate provisions, attesting to the logistics problem confronting the Patriots. Woodford considered Boykins’ behavior particularly egregious because his platoon was guarding the rebuilt bridge at Bachelor’s Mill that previously suffered damage by provincial Loyalists. Surviving correspondence indicates Boykins acquittal on December 26, 1775 was appealed by Woodford to the Virginia Convention, but upheld because of a lack of policy on the appeals process. All this to the dismay of Woodford.[28]

Capt. John Fleming, commanding a company in the 1st Virginia Regiment, was placed under arrest by his detachment commander, Maj. Francis Epps, on December 24, 1775 for neglect of duty. There is no record of a court martial. Captain Fleming continued to serve and was killed in action at Trenton on January 3, 1777.[29] Major Epps also gave his life to the cause, dying in combat on Long Island on August 27, 1776.[30] A court of inquiry also investigated allegations of Capt. Ballard, commanding a company in the 1st Virginia Regiment, for selling linens to the troops at inflated prices, but there are no records of the report or outcome.[31] Ballard continued to serve the Patriot cause, resigning as lieutenant colonel of the 4th Virginia in July 1779.[32]

Lt. Edward Vail of the 2nd North Carolina Regiment was the subject of a court martial; the charge and sentence were not recorded. Second Virginia Regimental Surgeon, Daniel Dougherty, was the subject of an inquiry for misappropriating a horse from one James Pinnell of Norfolk. It appears this case was dropped—perhaps he returned the horse?[33] Nonetheless, Woodford’s efforts to abide by his mentor’s guidance to “be strict in discipline” and to “discourage vice in every shape” are in ample evidence.

Today’s Army leadership doctrine stresses the importance of proper and professional military behavior to instill confidence and support of the civilian populace. [34] Washington’s concerns in highlighting the detrimental effects of vice on military discipline were both timely and timeless. Vice, particularly in the form of drunkenness, surfaced as the men occupied the City of Norfolk. Woodford’s efforts to curb this breach of military discipline appear less successful.[35] Woodford and Howe ordered all residents to leave Norfolk.[36] The troops began to occupy deserted dwellings and businesses. Liquor and wine left behind by residents and merchants who departed hastily appeared in good supply. After the British fleet began a bombardment of the city on January 1, 1776, chaos reigned. From January 2 through 5 there are no entries in the 2nd Virginia orderly book. As the city burned, the troops helped themselves to “hogshead of rum and pipes of wine.” They rolled them into the streets, “knocked in the heads, drank of the wine & filled their canteens & bottles.” They also set fire to houses and ran through the streets.[37] With insufficient forces to hold Norfolk, Woodford and Howe were happy to see the city destroyed to prevent future British and Loyalist reoccupation. By January 6, 1776 officers apparently reestablished order. The remaining undamaged structures were ordered destroyed by secret order of the Virginia Convention.[38]

Because gaming of all types was a popular pastime, it regularly plagued the Continental Army when in garrison. For the next few weeks, gaming became the vice of choice as Patriot forces destroyed what was left of Norfolk and moved inland to Suffolk, a more secure location away from the coast and the reach of the British navy.[39] Woodford, at least partly thanks to Washington’s guidance, worked diligently to counter the undisciplined and unruly actions of his soldiers.

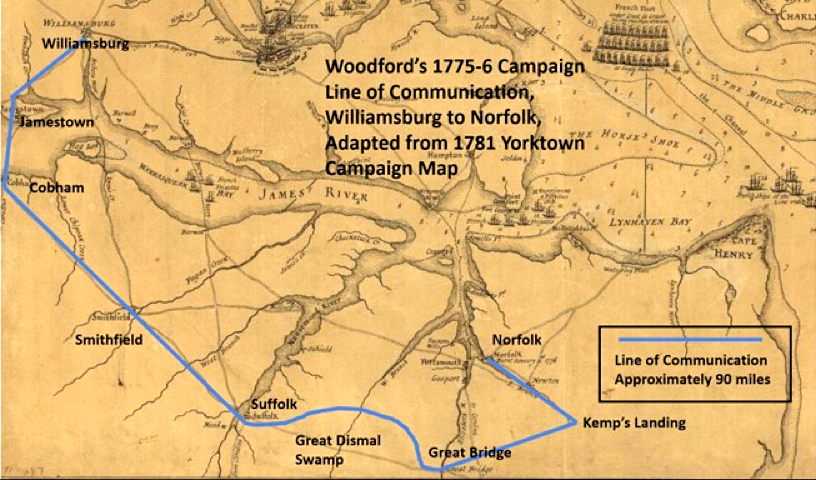

Regrettably, there is no clear and definitive record of Woodford receiving the military advice and guidance he requested in September that was outlined in Washington’s November 10, 1775 letter. Based on Woodford’s actions, it is highly probable he received and read Washington’s response early in the campaign, possibly before the December 9 Battle of Great Bridge. His actions and priorities exemplified the priorities listed by Washington. The Virginia Committee of Safety maintained regular and consistent communication between Williamsburg and Woodford’s headquarters. The route, about ninety miles between Williamsburg and Norfolk, involved a water crossing of several miles over the James River. This crossing required avoiding the patrolling vessels of the British navy, but was routinely safely traveled. The challenging circumstances necessitated a reliable network that supported steady stream of regular communication. After arrival in Williamsburg, Washington’s November 10, 1775 letter to Woodford would follow this path.[40] The letter very likely was delivered, and likely shaped Woodford’s actions.

Washington’s guidance and recommendations in his letter to Woodford, a fellow Virginian and newly appointed senior military leader, constituted sound advice. Washington routinely excelled as a counselor, coach and mentor to his many subordinates. His unique ability to assess and guide his fellow officers, and to shape many of his subordinate commanders in his own image, reckoned among the more important influences in winning the war.[41] Today’s military leaders should easily relate to the concepts contained in Washington’s guidance to Woodford. There is little doubt that the Army’s most recent edition of its principal leadership doctrine echoes some of the same basic leadership principles and traits found in Washington’s 1775 letter. Col. William Woodford’s action and success during his first major campaign reflect favorably on Washington’s ability to develop senior officers for independent command.

[1]George Washington to William Woodford, November 10, 1775, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0320.

[2]ADP 6-22, U.S. Army Doctrinal Publication, Army Leadership – The Profession, July 31, 2019, armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN20039-ADP_6-22-001-WEB-0.pdf.

[3]Ibid, 1-7; ADP 6-22 overtly contains numerous George Washington historical quotes to reinforce leadership ideas and principles.

[4]Although Woodford lacked experienced company grade leadership, several companies fielded men from western Virginia with experience in fighting the Native Americans; most of these units arrived later in the campaign because of the distances involved. Several of Woodford’s field grade officers were combat veterans of the French and Indian War. These included: Lieut. Col. Thomas Bullet, Woodford’s engineer and adjutant general of Virginia forces; Lieut. Col. Charles Scott of the 2nd Virginia Regiment; and Maj. Thomas Marshall, Culpeper Minute Battalion.

[6]John E. Selby, The Revolution in Virginia 1775-1783 (Williamsburg: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1988), 46-47.

[7]ADP 6-22, 1-13 & C1; defines leadership as “the activity of influencing people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to accomplish the mission and improve organization.”

[8]All quotes above from, Washington to Woodford, November 10, 1775. The books included Humphrey Bland, A Treatise of Military Discipline (9th ed., London, 1762); Lancelot Théodore, comte de Turpin de Crissé, An Essay on the Art of War, translated by Capt. Joseph Otway (London, 1761); Roger Stevenson, Military Instructions for Officers Detached in the Field (Philadelphia, 1775); Captaine de Jeney, The Partisan: or, The Art of Making War in Detachment, translated by J. Berkenhout (London, 1760); and William Young, Manœuvres, or Practical Observations on the Art of War (London, 1771); see Washington to Woodford, November 10, 1775.

[9]Robert L. Scribner and Brent Tarter, eds., Revolutionary Virginia, The Road to Independence, The Breaking Storm and the Third Convention, 1775 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1977), 3:457-8.

[10]Henry Mayer, Son of Thunder, Patrick Henry and the American Republic (New York: Grove Press, 1991), 269-285.

[11]Brent Tarter, “The Orderly Book of the Second Virginia Regiment: September 27, 1775-April 15, 1776,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 85, no. 2 (April 1977), 156-183, continued in 85, no. 3 (July 1977), 302-336.

[12]The Virginia Gazette (Dixon & Hunter), October 28, 1775.

[13]“Orderly Book,” 173n54. On October 25, 1775, the Virginia Committee of Safety directed William Woodford to cross the James River, “March to the neighborhood of Norfolk or Portsmouth,” and secure the area.

[15]Ibid., 302. Woodford’s general orders for December 8, 1775 also emphasized the dangers of leaving camp without orders and addressed proper hygiene as protective measures.

[16]Thomas Bullitt served as the adjutant general of the two Virginia regiments as well as the engineering officer. Scribner,Revolutionary Virginia, 3: 459; John Burke, History of Virginia from Its First Settlement to Present Day (Petersburg, VA: Dickson & Pescud, 1805), 439. 441-445.

[17]Richard K. Meade to Theodorick Bland, December 18, 1775, The Bland Papers: being a selection from the manuscripts of Colonel Theodorick Bland, Jr.; to which are prefixed an introduction, and a memoir of Colonel Bland, Charles Campbell, ed. (Petersburg: Edmund & Julian Ruffin, 1840), 1:38-39.

[18]Washington to Woodford, November 10, 1775.

[19]Woodford to Pendleton, December 5, 1775, D. R. Anderson, ed.,Richmond College Historical Papers (Richmond, VA: Richmond College, 1915), 110-12; Burk, History of Virginia, 444-5.

[20]Woodford to Pendleton, December 4, 1775, Richmond College Historical Papers, 106-9.

[21]Ibid. Several days after the fight at Great Bridge two large reinforcements arrived, Col. Robert Howe with the 2nd North Carolina Regiment and Major Epps arrived with a detachment of the 1st Virginia Regiment, increasing the size and capability of the force but also stressing the available logistical support.

[22]Meade to Bland, December 18, 1775, Bland Papers, 39.

[23]“Orderly Book,” 306n87, 308; Return of Forces under command of Col. Howe, at Norfolk, December 17, 1775, Peter Force, ed., American Archives, ser. 4, 4:294, archive.org/details/AmericanArchives-FourthSeriesVolume4peterForce/page/n147/mode/2up.

[24]Robert Howe to the president of the Virginia Convention, December 15, 1775; Woodford to the president of the Virginia Convention, December 15, 1775, Force, ed., American Archives, ser. 4, 4:278-994, archive.org/details/AmericanArchives-FourthSeriesVolume4peterForce/page/n137/mode/2up.

[25]“Orderly Book,” 305n84;Francis Bernard Heitman, Historical Registrar of Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution (Washington: The Rare Book Shop Publishing Co. Inc., 1914), 390.

[27]The Orderly Book contains numerous references to courts martial and inquiries often including the names of the officers appointed. Unfortunately, the findings and disposition of these cases rarely appear.

[28]“Orderly Book,” 311-13; Woodford to Convention, December 25, 1775; Alexander Spotswood, Court Martial Report, December 26, 1775, Richmond College Historical Papers, 140-3; Boykins Tavern, circa 1800, owned by Francis Boykins of Isle of Wright County, Virginia, was preserved and is the only remaining historic building near the original county court house from this period.

[29]“Orderly Book,” 311; Heitman, Historical Registrar, 230.

[30]Heitman, Historical Registrar, 217.

[32]Heitman, Historical Registrar, 84.

[36]Ibid., 316, Howe and Woodford ordered all Tories out of Norfolk on January 14, 1776 but many had departed a month earlier, taking refuge aboard British shipping in the harbor as Patriot forces entered Norfolk. The mass exodus significantly reduced the population. In 1775 Norfolk was the eighth largest city in North America with a population over 6,000; by mid-February the city no longer existed, burned to the ground.

[39]Entries in the orderly book provide a timeline for the events involving the destruction of Norfolk and the Gosport Shipyard in Portsmouth by Patriot forces. Also see Virginia Gazette(Purdie), February 9, 1776. The task force established headquarters in Suffolk on February 15, ending major operations in Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties during this initial campaign south of the James River; see “Orderly Book,” 324.

[40]The Williamsburg to Norfolk land route crossed the James River near Jamestown; proceeded through Cobham Plantation, and Smithfield, Isle of Wight County; to Suffolk, Nansemond County; around the north end of the Great Dismal Swamp to Great Bridge, Norfolk County; to Kemp’s Landing, Princess Anne County; then on to Norfolk. Reviewing the Journals of the Convention and accompanying letters indicates a steady flow of timely communication between Woodford’s task force and the Committee of Safety in Williamsburg. This kept the Committee and larger Convention, when in session, advised on the military situation while providing timely guidance to the commanders.

[41]George Athan Billias, ed., George Washington’s Generals (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1964), xvii.

Recent Articles

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

Recent Comments

"Contributor Question: Stolen or..."

Elias Boudinot Manuscript: Good news! The John Carter Brown Library at Brown...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

The new article by Victor DiSanto, "The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched...

"Quotes About or By..."

This well researched article of selected quotes underscores the importance of Indian...