In 1777, the third year of the American War for Independence, little had gone in the favor of the Patriots especially in the borderlands. They controlled Fort Pitt and several other outposts, but they were far from the main fighting; the region was considered a backwater theater. British governor of Detroit Henry Hamilton issued a proclamation that encouraged Native Americans to attack rebel settlers in the region.[1] Hamilton’s proclamation created a panic among frontiersmen as they remembered Pontiac’s War in 1763-1764 and the more recent Lord Dunmore’s War in 1774. The British hoped the renewing of an Indian war would force the rebels to send valuable resources to the western borderlands, ultimately weakening American forces in the east. Hamilton’s Proclamation reignited the racial hatred of the frontiersmen against Native Americans, and they used the banner of war to exact revenge against their enemies—indigenous and Anglo alike.

Despite the remote nature of the frontier, Fort Pitt and junction of three rivers that it overlooked was a strategic position controlling commerce and travel that would be important for the young republic. The Second Continental Congress, even before Thomas Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence, understood the importance of the Western Department. Congress wanted a military and Native American diplomat that knew the region and people. In April 1776, they commissioned merchant George Morgan to be a colonel in the Continental Army and chief Indian agent at Fort Pitt. Morgan himself had no military experience, other than working with the British Army before the American Revolution. His personal experiences with the British Army included dealing with corrupted officers like Lt. Colonel John Wilkins, who acted like tyrants, so it is no wonder Morgan joined the American cause. In addition to Morgan, Gen. George Washington sent Gen. Edward Hand to Fort Pitt along with about 3,000 militiamen to secure the American frontier. Hand, born in Ireland, was a doctor who served in the British Army as a surgeon’s mate during the Seven Years’ War. With a shortage of experienced officers, Hand rose quickly through the ranks of the Continental Army. He went to Fort Pitt to secure the region and protect it from British and Native American attacks, and to also keep the peace in local matters.

Years prior during Lord Dunmore’s War, in 1774, the local population became embroiled in civil conflict. The personal grudges and rumors created a volatile atmosphere even before Hand arrived. Additionally white settlers, especially the ones that experienced Pontiac’s Rebellion, painted anyone friendly to any Native American group as a Tory. Their patriotic fervor overshadowed their racial prejudice against indigenous people. These frontiersmen also distrusted the Continental Army as they felt the elite officers worked with Native Americans rather than enacting their own brand of justice—genocidal justice.

As Fort Pitt and the surrounding areas were on the periphery of the action during the War for Independence, this episode is often ignored in the larger narrative of the American Revolution. The frontier militias believed that Continental leaders such as Col. George Morgan and even General Hand secretly worked with the British as they openly met with Delaware and Shawnee leaders. Because the details of the meetings were secret, many militiamen suspected treason.

In late December 1777, General Hand returned to Fort Pitt from Fort Randolph to learn of the arrest of Morgan, the Indian Agent for Congress. Hand was also accused of being in a Loyalist plot to hand over Fort Pitt to the British. More Patriot leaders became embroiled in the alleged Tory plot. In addition to Morgan and Hand, the militia suspected Col. John Campbell, Capt. Alexander McKee, and Simon Girty of being in league with the Native Americans and British.[2]

Many suspected George Morgan because he had a close relationship with Capt. Half Pipe and Capt. White Eyes of the Delaware. Often Morgan left Fort Pitt for extended periods of time to meet with Indian leaders as he represented the United States in diplomacy.[3] Those trips seemed curious to the militia, as Indian attacks did not seem to stop. News of Morgan’s suspicious movement led to locals asking Congress to investigate his actions. On October 22, 1777, Congress resolved to set up a committee of inquiry to examine Morgan’s alleged corruption.[4] During the time of the investigation Morgan refrained, as much as he could, from performing his duties as an Indian diplomat.

Local militia Col. Zachwell Morgan, the namesake of modern Morgantown, West Virginia, was the leader who brought charges of conspiracy against the suspected Tories. Frontier militias patrolled the region and reported all Loyalist and Native American activities. Additionally, there was a string of indigenous leaders’ murders that took place throughout the summer and into the fall. Frontier militiamen were the main culprits for these killings, which threatened the peace that Morgan and other American officials had brokered with local tribes.

One such case was the murder of Cornstalk, a pro-American Shawnee leader, who was mistakenly captured at Fort Randolph. During Cornstalk’s and several other Shawnees’ imprisonment, a militia man named Robert Gilmore was killed during a hunting trip. The local militia at Fort Randolph believed the culprits to be Indians and with little thought they executed their captives including Cornstalk; “seven or eight bullets [were] fired into him, and his son was shot dead” too.We know about Cornstalk’s murder because of Capt.John Stuart’s account, where he claimed “I have no doubt if he had been spared but he would have been friendly to the Americans for nothing could have induced him to make the visit to the garrison at that critical time.”[5] Reports from militia officers Capt. Matthew Arbuckle and Captain Stuart suggest that they told their men to stand down, but they refused to listen to orders and continued to murder the four Shawnee prisoners. At the very least these officers deflected blame to their own soldiers.

News of Cornstalk’s murder spread throughout the region and to Virginia. Cornstalk’s death put the relationship between the young republic and the tribes on rocky ground. Additionally, frontier militias and Continentals had a tumultuous relationship as neither trusted the other. The militias had their own objectives and often disobeyed orders. General Hand had to restore order and investigate the incident at Fort Randolph.

During Hand’s absence from Fort Pitt, militia Col. Zachwell Morgan took it upon himself to detain Col. George Morgan. The news of George Morgan’s arrest reached General Hand and pushed him to hastily return to Fort Pitt in late December. Upon his arrival he discovered that the militia continued to harass suspected Tories. Hand offered George Morgan to stay with him at Fort Pitt, but he refused; he preferred house arrest because he was “very busy.”[6] Morgan’s refusal made him look more guilty to the local militia.

Other suspected Tories, including Colonel Campbell, took up Hand’s offer to stay with him, while Alexander McKee remained under house arrest and Simon Girty was sent to the “common guard-house.” Hand reported that during the testimonies of witnesses only one man mentioned Morgan as part of a plot. Because of the lack of evidence, Hand freed Morgan, although he still was under a congressional investigation until he was cleared on April 7, 1778. The committee acquitted Girty, but McKee had been paroled as there was some minor evidence of wrongdoing. Hand believed that Captain Arbuckle of the militia (the same one from Fort Randolph) had a feud with McKee and wanted him out of the picture.[7]

Eventually both McKee and Girty would defect to the British side after their poor treatment by the American militia. The others that remained loyal to the Patriot cause like Morgan would still be under suspicion despite being cleared of wrongdoing. Simply put, it was Morgan’s pro-Indian stance that made him an enemy to the frontiersmen.

With the Tory plot accusations behind him, Morgan returned his duties as an Indian agent for the United States. He went to counsel the Shawnee after the murders of Cornstalk and others at Fort Randolph. Morgan relayed, “When I look toward you or at the Kenawa River I am ashamed of the Conduct of our young foolish Men.”[8] The Indian agent’s diplomacy worked and the Shawnee held fast to their friendship with the United States. Morgan recorded in a letter to the Moravian missionary David Zeisberger that “it rejoices me exceedingly to hear that Captain Pipe, Captain White Eyes, Captain Killbuck, and all the other wise Delaware Chief resolve to remain our Friends.”[9] Morgan’s diplomacy was a delicate balancing act that seemed to work.

Unfortunately, at the same time Morgan worked to patch up the relationship between the Delaware, Shawnee, and the United States, General Hand led 500 militiamen from Westmoreland County on an ill-advised mission westward into Indian territory. Almost from the start Hand’s campaign was a failure. Plagued by bad weather and high water, at Beaver creek scouts reported that a native settlement was nearby, and the militia proceeded to attack the village. The undisciplined militia indiscriminately killed the indigenous peoples at the settlement. Hand recalled that “But to my great Mortification found only one Man with some women and Children . . . the Men were so Impetuous that I could not prevent their Killing the Man and one of the women.”[10] The disastrous expedition climaxed when Hand realized the militia had attacked a friendly Delaware, village killing members of Capt. Half Pipe’s family. Hand’s disgraced mission led to him to ask to be recalled. Later that spring, Washington recalled him and replaced him with a new more aggressive commander.

In May 1778, Gen. Lachlan McIntosh became the commander of the Western Department for the Continental Army, becoming Hand’s superior. McIntosh, a Scot from Georgia who killed Button Gwinnett over a political feud in 1777, traveled to the American west to find it in disarray in August 1778; his predecessor could not control the militias or the Native Americans (friendly or hostile).[11] McIntosh believed that a new westward campaign to capture Fort Detroit could bring him glory and honor, and ultimately put an end to the Indian war provoked by Hamilton’s Proclamation. The problems with any campaign in the west, though, were logistics and getting enough volunteers.

McIntosh intended for a new expedition, but in order to accomplish this feat he needed allies among the Native American tribes. One thing stood in his way: George Morgan’s diplomacy. Morgan kept the peace because he acknowledged the Native Americans’ wish to be neutral in martial activities. The Indian stance was not one that McIntosh wanted, and he sought to renegotiate the peace with the Shawnee and Delaware without Morgan present.

When Morgan was away from Fort Pitt in September 1778, McIntosh welcomed Delaware leadership in order to hammer out a new treaty that included military support for an attack on the British at Detroit. Captains White Eyes, Half Pipe, and John Killbuck were in attendance with General McIntosh and Colonels Daniel Brodhead and William Crawford. With Morgan’s absence, the Delaware were taken advantage of as they believed the treaty only suggested to give free passage to the army and permission to build new forts in their territory. However, it was a military alliance that also promised the creation of a fourteenth state, a Lenape state with representation in Congress.[12] Like many other Native American treaties through history, the Fort Pitt Treaty of 1778 would be routinely ignored by the United States government.

Almost immediately Morgan and McIntosh were at odds with each other. Morgan’s pro-Indian stance and his role as the deputy commissary general for the western department put him in an awkward position with the commander. In late 1778, McIntosh launched a campaign to attack Fort Detroit. He and the militia left Fort Pitt and ventured to Fort McIntosh and then to Fort Laurens. Along with the American forces was Capt. White Eyes as a guide. Unfortunately, White Eyes died only a few days into the expedition. Official reports suggest he developed smallpox and died. Other accounts contradict the official report by saying the militia assassinated the Delaware leader. Even George Morgan did not believe the official report; years later he told Congress he believed that White Eyes was “treacherously put to Death, at the moment of his greatest Exertions to serve the United States.”[13] Whether or not McIntosh knew about the murder of White Eyes will never be known, but reports that militiamen were the culprits make the most sense. As shown by the earlier execution of Cornstalk, frontier militias put little value in native lives. As McIntosh’s mission failed to achieve its desired effect the militia’s frustration could have led to White Eyes’ murder.

The feud between the two officers grew into a political spat that caught the attention of congressman Governour Morris and Gen. George Washington. McIntosh believed that Morgan kept “almost all his public business in this Dept. a profound Secrete from me among his other Schemes.” The commander considered Morgan to be corrupt and to have his own agenda contrary to his own. McIntosh illustrated his perspective to Washington, writing, “I cannot help observing here sir, of this Gentleman & others who have Separate Views & Connections, & a Variety of Lucrative Offices to bestow, Independent as they think of any person who Commands in the Department.”[14] In the same letter, McIntosh asked Washington to reassign him, as the Western Department was a difficult assignment because of Morgan, the Native Americans, and the militias. Additionally, McIntosh was almost universally hated by his troops and native allies alike.[15] McIntosh, like Hand, could not control the militia.

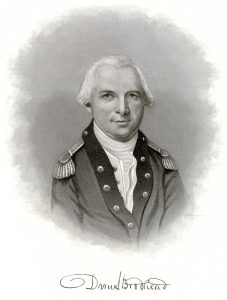

Colonel Daniel Brodhead took over command of the Western Department. Despite McIntosh’s recall, American relations with the Delaware and Shawnee were precarious at best. Morgan’s progress with the Shawnee and Delaware all but evaporated with GeneralHand’s infamous campaign, the Fort Pitt Treaty of 1778, McIntosh’s aborted expedition to take Detroit, and White Eyes’ assassination. Only John Killbuck’s band remained loyal to the United States, but even he often pleaded with American officials to forgive his foolish brethren. Despite his loyalty to the Americans, he often felt uneasy at Fort Pitt because of the militia who threatened his life.[16]

After Colonel Brodhead took command he attempted to repair the diplomatic damages on the frontier, but General Washington ordered him to maintain the outposts of Fort McIntosh and Fort Laurens, which were in Delaware and Shawnee territory.[17] Washington also expressed his interest in continuing the fight against the western tribes. Washington relayed to Brodhead, “it is my wish however, as soon as it may be in our power to chastise the Western savages, by an expedition into their country.”[18] Washington reminded that “It is of Importance most certainly to preserve the friendship of the Indians who have not taken up the Hatchet,” but they did not have presents or gifts to award their native allies.[19] Washington did not see the Delaware and Shawnee as enemies like the local militias did.

Unfortunately, like McIntosh, Brodhead had a hard time keeping discipline among the militia. Brodhead blamed local settlers who often sold liquor to the soldiers, which led to fights and even murders. One such incident occurred when a private from the 13thVirginia Regiment “maliciously killed one of the best young Men of the Delaware Nation.” Brodhead did not have enough field officers to conduct a proper trial and did not want to hand him over to civilian magistrates because he feared that the soldier would escape punishment.[20] Eventually, the court martial acquitted Pvt. James Beham of the murder on June 9, 1779.

The war in the borderlands was a different kind of conflict, one of retribution and attrition. Since the Treaty of 1778 the number of friendly Native American bands began to shrink, and the Patriot army on the American frontier really did not have much support. When Brodhead took over command of the Western department he had few regular soldiers, which meant that he had to rely on local militiamen who were often more focused on revenge than on any larger military objective.

Washington’s orders were to chastise the western tribes, but he also sent Gen. John Sullivan into Iroquoia to punish those tribes who decided to aid the British. Sullivan’s campaign was a seek and destroy mission into Indian country. Colonel Brodhead sought out glory to advance his career, so he wanted to link up with Sullivan’s army as they ventured into Iroquoia. With about 600 men, mostly militia, Brodhead left Fort Pitt on August 11, 1779, to harass the Seneca north of Pittsburgh near modern Warren, Pennsylvania. Brodhead exclaimed to Washington that “It would give me great pleasure to Co-operate with Genl Sullivan but I Shall be into the Seneca Towns a long time before he can receive an account of my Movement.” Brodhead moved into Seneca lands long before Sullivan arrived. But he believed if his mission against the Seneca was successful, he could then go link up with Sullivan “to reduce Detroit and its dependencies.”[21] Ultimately, Brodhead dreamed of taking Detroit, even if his army really did not have the capability.

When Brodhead’s advance party consisting of fifteen Americans and eight Delaware “discovered between 30 & 40 warriors landing from their canoes . . . [they] prepared for action.”[22] A firefight ensued with limited success. Despite this small skirmish at Thompson’s Island, Brodhead’s campaign north only burnt abandoned villages and cornfields and did not have any significant outcome. By mid-September 1779, the Americans returned to Fort Pitt without linking up with Sullivan’s army and without going to Detroit. For Brodhead, this mission was a failure.

In the following years, Brodhead remained commander of the Western Department and continued to use the militia to launch a campaign against the Turtle Clan of the Delaware in Ohio, whose leader White Eyes had been assassinated. Under White Eyes they wanted to maintain their neutrality in the conflict, but rumors swirled that they were joining the defected Half Pipe and his British allies. Attacks and raids on American settlements by Native Americans, such as an incident in March 1780 at “Sugar Camp upon Raccoon Creek in Yoghagania County” where five men were murdered and “three Girls & three lads” were taken prisoners, only fueled more rage. Frontiersmen “conjectured that the Delawares perpetrated this Murder, but it is possible it may have been done by other Indians.”[23] These raids prompted Brodhead to support Col. George Rogers Clark and his campaign against Native Americans further west with the old objective of taking Detroit.

With reports of the Delaware treachery, Brodhead with about 300 men, a mix of regulars and militia, set out to Coshocton in Ohio. There they hoped to convince the Delaware to remain with the United States but militiaman Martin Wetzel murdered a Lenape leader, spoiling the peace council. Frontiersmen like Wetzel wanted revenge against raids and murders. Eventually the Americans refocused their objectives and Brodhead and his men attacked and destroyed the villages of Coschocton and Lichtenau, where they captured fifteen warriors and executed them.[24] For Brodhead this campaign was to punish hostile Indians, so he spared most of the Moravian Christian villages.

Again, this campaign did not satisfy Brodhead as he wanted to connect with Colonel Clark to take Detroit. Despite his obsession with Detroit, his men, mostly frontiersmen, were satisfied with murdering, pillaging, and razing Indian villages close to their homesteads. As Brodhead returned his force to Fort Pitt, renewed Indians raids descended on the Pennsylvania borderlands. Many of the county militia were not successful in protecting settlers and they wished to take the war to the natives.[25] The years 1780 and 1781 witnessed persistent Indian attacks on settlements and the militia had little success defending them. Additionally, supplies ran low for the army, but Brodhead continued to plan an expedition to Sandusky for the autumn of 1781. He wrote, “The Country appears to be desirous to promote it; and I intend to command it if they the Militia & Volunteers do not suffer themselves to be induced into a belief that I have no right to command.”[26] Brodhead and his second in command Colonel John Gibson squabbled over the direction of their mission in the Western Department. This feud led to Brodhead’s removal from command. Brigadier General William Irvine replaced him at Fort Pitt in November 1781.

Without orders from Brodhead the army command was in disarray. Militia Col. David Williamson of Washington County led his men to the Moravian Indian villages that Brodhead visited in 1780. They discovered the villages were mostly abandoned and they captured the remaining Indians, who were Christians. The prisoners were taken to Fort Pitt and released once they learned they were Moravian.[27] Their release continued to upset the local population, as they believed the Moravian Indians were involved in the recent raids. Historian Eric Sterner has argued that was one of the major motivations for the Gnadenhutten massacre.[28]

Angry at the continued attacks, the Pennsylvania militia returned to the pacifist Moravian Indian villages to punish any Indian they found. The vengeful militia under Williamson entered the village of Gnadenhutten on March 7, 1782, as many of the villagers tended their fields. Williamson convinced the villagers that they just wanted to take them to Fort Pitt for safety as an attack was imminent. What happened next was one of the most brutal acts in American history. The Pennsylvania and Virginia militia rounded up the Indians and informed them they were sentenced to death.[29] They used a cooper’s mallet to execute the Delaware men, women, and children. On that late winter day, ninety-six Christian Indians were brutally executed while the militia plundered and razed the village. The violence continued as the frontier remained an open battlefield with little knowledge of who was a friend or foe.

Later in the spring, Col. William Crawford and Colonel Williamson raised a force of Pennsylvania militia to attack the hostile Wyandot and remaining Lenape that resided in Sandusky. Their plan was to attack Indian villages and towns near Sandusky, however, without a clear plan they were outnumbered and had to retreat. During the hastily retreat, Crawford and some men were captured by some Delaware. They ritually tortured and burnt Crawford at the stake in revenge for the Gnadenhutten massacre just a few weeks earlier.

The militia continued to attack any Indian they came across as they believed that all Native Americans were the enemy. Since it was the periphery of the Revolutionary war, there was little martial order, and Continental Army officers lacked any authority over the militia. Hand, McIntosh, Brodhead, and Irvine all failed in their objectives as they could not control discipline among their troops, especially those of the local militia. Under the banner of war, the militia’s unsanctioned violence prolonged hostilities on the frontier which claimed many innocent victims—Native and Anglo alike. With the Treaty of Paris in 1783, a tentative peace returned to the borderlands, but war would return in 1790 in the form of the Northwest Indian Wars.

[1]“Hamilton’s Proclamation, June 24, 1777” in Frontier Defense on the Upper Ohio, 1777-1778, Reuben Gold Thwaites and Louise Phelps Kellogg (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1912), 14.

[2]“Loyalists at Fort Pitt,” ibid., 184-185.

[3]“Loyalists at Fort Pitt,” ibid., 186.

[4]Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904-1937), 9:831.

[5]“The Murder of Cornstalk” in Frontier Defense on the Upper Ohio, 160.

[6]“Loyalists at Fort Pitt,” ibid., 184-185.

[8]“Conciliating the Shawnee, George Morgan, March 25, 1778,” ibid., 234.

[9]George Morgan to David Zeisberger, March 27, 1778, George Morgan Letterbook, Volume III, Carnegie Library Pittsburgh.

[10]”One hundred and forty-five letters from Gen. Hand to Jasper Yeates, dealing with the American revolution,” digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/c09184da-bbf6-a756-e040-e00a1806216b.

[11]Harvey H. Jackson, Lachlan McIntosh and the Politics of Revolutionary Georgia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003), 74.

[12]avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/del1778.asp.

[13]George Morgan to the President of Congress, May 12, 1784, Papers of the Continental Congress, NARA, RG 360, M247, item 163, roll 180, pages 365-367, fold3.com.

[14]Lachlan McIntosh to George Washington, March 12, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-19-02-0457.

[15]Daniel Brodhead to Washington, January 16, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-19-02-0008.

[16]David Zeisberger, Diary of David Zeisberger, Eugene F. Bliss, ed.(Cincinnati: R. Clarke & Co, 1885), 420.

[17]Washington to Brodhead, May 3, 1779,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0268.

[18]Washington to Brodhead, April 21, 1779,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0132.

[19]Washington to Brodhead, May 3, 1779,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0268.

[20]Brodhead to Washington, May 3, 1779,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-20-02-0269.

[21]Brodhead to Washington, July 31–August 4, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-21-02-0599.

[22]“Extract from Maryland Journal,October, 26, 1779,” in Louise Phelps Kellogg, Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio, 1779-1781(Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1981),57.

[23]Brodhead to Washington, March 18, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-25-02-0059.

[24]Randolph C. Downes, Council Fires on the Upper Ohio: A Narrative of Indian Affairs in the Upper Ohio Valley Until 1795(Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1977), 265.

[25]Brodhead to Washington, May 30, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-26-02-0164.

[26]Brodhead to Washington, August 23, 1781,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-06764.

[27]David Curtis Skaggs, and Larry L. Nelson, The Sixty Years’ War for the Great Lakes, 1754-1814 (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2010),197.

[28]Eric Sterner, Anatomy of a Massacre: The Destruction of Gnadenhutten, 1782 (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2021).

[29]Not all militiamen were in favor of the mass execution. A few returned home because they did not agree with the actions in Gnadenhutten.

One thought on “Under the Banner of War: Frontier Militia and Uncontrolled Violence”

Nice piece. I’m looking forward to your bio of Thomas Hutchins. I crossed paths with him a few times in studying the frontier and got a kick out of his “Topographical Description.” Quite an interesting character worthy of a bio in his own right.

One of the things I’ve learned since writing about the militia for JAR is the need to distinguish between proper militia actions and ad hoc volunteer groups, which were often constituted for a specific, short-term purpose. While it is true that the same men served in both, the difference can be more important than semantics. It tells us something about accountability and policy while shedding some insight into differences between locals, local political authorities, state authorities, and Continental authorities, which you really dug into in Morgan’s case.

I initially assumed the militia carried out the the Gnadenhutten massacre because almost every history that mentioned the event assumed so. But, digging a little deeper, I had to conclude that the original sources–Joseph Doddridge and Moravian accounts–had gotten it wrong and their errors had been repeated for nearly two centuries. A stronger case was that the raiding party was created outside the authority of the militia system specifically to avoid the kind of oversight and accountability that went with the system. Partly in reaction to the massacre, the subsequent campaign to the Sandusky became something of a hybrid. It was an ad hoc volunteer group. No militia classes were called up for it and the commanders were selected outside of the established militia chain of command. But, to encourage volunteers for the ad hoc group, the county lieutenants offered to credit volunteers with some time under their militia obligations. It created an odd situation in which PA counties were unable to honor their promises to call up sufficient manpower to help secure the frontier due to the sudden exodus of manpower for the campaign!

Food for thought, anyway.