In July 1783 John Jay, one of the Americans negotiating a treaty of peace between Great Britain and the United States, was sitting at his desk. The negotiations, taking place in Paris had been going on for some months with much quibbling over language, borders, trading rights, and fishing rights. Sentences were being written and rewritten over and over again. Now as the negotiations were entering their final stage, Jay sat down and thought of the future. He had some concerns and he wrote to Charles Thomson, Secretary of the Continental Congress about them.

Jay had met Thomson when he was a member of the First Continental Congress that met in August 1774. Jay was a delegate from New York and was considered a moderate. John Adams, a radical from Massachusetts, did not think much of Jay at the time. A number of colonies had chosen radicals in the resistance to Britain as their delegates, with the most radical delegates coming from Massachusetts and Virginia. There quickly developed an alliance between the Adamses of Massachusetts and Virginians Richard Henry Lee and Patrick Henry. There were moderates like John Jay of New York and John Dickenson of Pennsylvania as well as conservatives like Joseph Galloway of Pennsylvania and James Duane of New York.

On the first day of the congress, it was decided that someone needed to be the secretary. The conservatives had centered on James Duane, the moderates on Silas Deane, but the radicals reached outside the membership of the congress and chose Charles Thomson. He was the most radical leader in Philadelphia and had been deliberately left off the Pennsylvania delegation by the Pennsylvania legislators, thinking they would isolate him from any influence in the congress. Instead, the conservatives found that the radicals had behind the scenes already rounded up enough votes to make him the offer of secretary by a wide margin. Thus, Charles Thomson became a central part of the congress. He was the only one to stay in his position throughout the whole fifteen years of the Continental Congress. No document was official without his signature. Many times, especially after the war, there were days and weeks when he was the only one in attendance. When the others went home, he alone was the government of the United States. He sat on many committees as the secretary. He undoubtedly had influence in unofficial discussions on the issues facing the congress. Over the years he developed a reputation for honesty and fairness.

It was natural for Jay to consider that Charles Thomson was particularly well suited for the special task he had in mind. Jay was concerned that with the coming of peace, Americans would start competing for credit about winning the revolution. He knew only too well that the Continental Congress had been full of factions and partisanship throughout the revolution. He himself had, during the early days of the first Continental Congress, belonged a factionbelieving inmoderation on independence and dealing with Great Britain, while fellow peace negotiator John Adams had been a leader in the radical group, primarily from Massachusetts and Virginia, who wanted an aggressive posture and were early in calling for independence. During the ensuing years members of Congress had sparred over issues such as the abolition of slavery, the extent to which the United States should be subservient to France—a nation that had provided essential financial and military support—and a host of other issues. Now with independence won, everyone would be writing histories and memoirs each claiming that they or their favorite persons, or the faction that they belonged to, was the most influential and important in the victory.

Charles Thomson, Jay thought, was the one person to set the record straight. So Jay picked up his pen and wrote,

Passy, France, July 19, 1783

Dear Sir,

When I consider that no person in the world is so profoundly acquainted with the rise, conduct and conclusion of the American Revolution as yourself, I cannot but with wish that you would devote one hour in the four and twenty to giving posterity a true account of it. I think it might be comprised in a small compass. It need not be burdened with a minuteaccount of battles, retreats, evacuations, etc.; leave those matters to more voluminous historians. The political story of the Revolution will be most liable to misrepresentation, and future relations of it will probably be replete with intentional and accidental errors. Such a work would be highly important to your reputation, as well as to the cause of truth with posterity . . . With every sincere esteem and regard, I am Sir, your friend and servant.[1]

John Jay

Whether Charles Thomson considered Jay’s proposition at this time is not known; he was still busy in his role as secretary. The war was over and now a nation had to be built. Laws had to be formed, a system of finances arranged, diplomatic missions abroad maintained, a peace time army and navy regulated, a system of territories west of the Appalachian Mountains arranged and most important, a system for dealing with the Native Americans in this new nation established. The Continental Congress had lots of work to do. Charles Thomson remained at his post.

When, finally, a new government was formed in 1789, many of the old Continental Congress members were elected to positions within the new government. As such, many of the old feuds and factions and political disputes went with them. Charles Thomson, who had sided with none and made no political alliances, was left out. His last official act was to go to Mount Vernon and deliver the last message from the Continental Congress, that the new constitution had been properly ratified and that George Washington had been elected president and should report to New York City, the new capital. Thomson accompanied Washington to New York and there presented him with the official journals of the Continental Congress and all official papers and the seal of the United States. With that act Charles Thomson became unemployed.

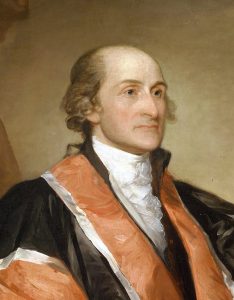

As the new government took form, John Jay, who had become the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, again wrote to Charles Thomson to remind him of his earlier commission.

New York, November, 1791

Dear Sir,

As we enter this, our new beginning in the history of our nation and have reflected on the fact that you are not a part of our new government, I know that you are disappointed in that omission. However, upon reflection I wonder if that may not turn out for the best. My friend, you have been at the very center, the heart of our Revolution, from the beginning to the end. Indeed, there have been times when all have let loose the responsibilities of government and duty. When others have absconded and abandoned their duties, you have remained at your post. During the fifteen years of our government in which the Continental Congress was our government and led us through the revolution and early days of peace and hard times, you have never failed your duty.

Then Jay reminded Thomson of his fears that the histories of the revolution would be inaccurate and full of partisan views, fears that since the end of the war had already begun to play out.

As you know, a number of persons, none of which have been as faithful from the beginning to the end, have written histories of our revolution. I have found them all wanting, either in completeness, candor, or truthfulness. They are almost all full of faction and point of view. You, my friend, who have been at the very center of it all, from the beginning to the end, can set the record straight. I am persuaded that heaven in its mysterious ways, have spared you of further employ to our country in order that you may perform one more, great and lasting service. You, my friend, should be the one to tell the story of our struggles as a nation. Only you were there from the beginning to the end, only you have the reputation to tell the story as it really happened without regard to faction or personality. Do this, my friend, do his great service for your country and posterity.

Your obedient Servant. John Jay

This time Thomson gave Jay’s letters some thought. He did start his history. But he must have wondered if his narrative would have any place in America. Americans had already written their history based on what they saw with their hearts rather than their minds. The truth would have no place in American history. After burning all his papers in 1815 he wrote to John Jay, “No . . . I ought not, for I should contradict all the historians of the great events of the Revolution . . . Let the world admire the supposed wisdom and valor of our great men. Perhaps they may adopt the qualities that have been ascribed to them, and thus good may be done. I shall not undeceive future generations.”[2]

With the destruction of Thomson’s papers one of his biographers wrote that “much of the truth about the revolutionary period is gone forever.”[3] Another wrote that “Whatever the cause which inspired [Thomson] to destroy his papers, the loss to history was an irreparable one.”[4]

[1]John Jay to Charles Thomson, July 19, 1783, The Revolutionary Diplomatic Correspondence of The United States, Francis Wharton, ed. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1889), Volume 6.

[2]Boyd Stanley Schlenther, Charles Thomson: A Patriot’s Pursuit (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1990), 204-205. Italics by author.

[4]Lewis R. Harley, The Life of Charles Thomson (Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1900), 160.

2 Comments

This sounds like a good plot for a novel or a movie: Charles Thomson did not actually destroy his papers, and they were simply put away, forgotten, and passed down from one generation to the next. They are discovered two hundred years later in an attic; they reveal secrets about the Founding Fathers. A controversy ensues, can they be published? Whose reputation will be harmed? The letters go missing! A private detective is hired. The chase begins. Rumors. lawsuits. blackmail. A thrilling ending.

M.R. J.M.S.’s book Undeceived: A Political History of the American Revolution as Inspired by Charles Thomson, was on my Amazon wishlist for years. It’s time to order it.