The efforts of a group of self-taught Patriot spies who would later become known as the Culper Spy Ring played an important role in winning independence from Great Britain. But their story still has many missing pieces, and unfortunately legend and even unsubstantiated speculation have filled the gaps.

From experience in the French and Indian War, the Continental Army commander, Gen. George Washington, knew that gaining intelligence of British military actions through a spy network was critical if his underdog army was to have a chance of successfully fighting the one of the strongest military powers in the world. So when the British gained control of New York City and Long Island in autumn 1776, Washington began a long and difficult process of creating an espionage operation in the region.

Historians have long been fascinated by the intelligence efforts undertaken by enthusiastic amateurs. In more than a dozen books, researchers have tried to sort out who was involved and exactly what their roles were. The biggest mystery was the identity of Culper Junior, the chief spy in Manhattan in the later years of the war. Most of the spy ring operatives identified themselves or were identified after the war, but not Culper Junior. So when Long Island historian Morton Pennypacker revealed him to have been Robert Townsend of Oyster Bay in 1930 and then proved it with document analysis nine years later, it generated considerable attention.

Interest in the Patriots’ intelligence network soared when the AMC television series Turn: Washington’s Spies aired for four seasons between 2014 and 2017. Unfortunately, it took great liberties with the facts. These included having the ring created in 1776 rather than two years later, depicting Setauket as a neighborhood of stately stone homes rather than wooden structures, having the hamlet occupied by regular army redcoats rather than Loyalist troops, portraying Abraham Woodhull’s minister father as a Tory socializing with the occupiers rather than showing the reality of him being a Patriot sympathizer badly beaten by soldiers trying to find and arrest his son and, most ludicrously, having Woodhull and the happily married and older Anna Strong engage in a secret affair. But the series did get people reading and talking about espionage during the war.

As with Turn, Pennypacker and many of the authors who have written about the Culper Ring subsequently have strayed from the truth. Pennypacker’s books, which lack footnotes, transformed some anecdotal information and legends into fact. And later writers have often repeated that material without researching or even questioning it. And while they may have sought information from Long Island historians who have spent decades studying the subject, they didn’t always listen to them.

The most prominent writer in that category would be Fox News co-host Brian Kilmeade, who lives on Long Island. In preparing his 2013 bestseller with coauthor Don Yaeger and other writers, he convened gatherings of local historians from Culper-connected locations such as Setauket and Oyster Bay. They provided him with much information, some of which he ignored when it didn’t fit into his narrative. He also strayed into historical fiction by filling the book with invented dialogue without indicating that the words were never spoken by the participants.

Kilmeade’s work is also filled with supposed statements of fact that can be disputed. These start with the title and subtitle of the book: George Washington’s Secret Six: The Spy Ring That Saved the American Revolution. In a volume lacking footnotes and offering only a smattering of sources, the authors state that the spy ring consisted of exactly six individuals. Many more than that were involved in the operation, including couriers and boat captain Caleb Brewster. He played a critical role in carrying messages across Long Island Sound to get them to Washington’s headquarters. Without Brewster there is no Culper Spy Ring. The authors have Robert Townsend playing the central role. While he was certainly important and the main source of information from New York City in the later years, the chief spy who coordinated the espionage throughout the war was Abraham Woodhull of Setauket. Without him, the spy ring never would have functioned.

Furthermore, Kilmeade and Yeager include two individuals among their chosen six who are questionable: James Rivington and a mysterious woman they label only as “Agent 355.” Local historians have concluded that Rivington, publisher of a Loyalist newspaper in Manhattan, is unlikely to have served as a spy and was definitely not part of the Culper Ring. They, and other historians, believe there was no Agent 355. And while other historians generally agree the Culper network played an important role, no one else goes as far as to say that it “saved the American Revolution.” Their contention that the spy ring “broke the back of the British military” is hyperbole.[1]

Early Intelligence Gathering

After operating with little useful intelligence before and after the Battle of Long Island in late August 1776, Washington took action to fill his intelligence vacuum in the fall. While still based in Manhattan, he instructed Col. Thomas Knowlton to select a group of men to undertake reconnaissance missions. The unit became known as Knowlton’s Rangers.[2] Its most famous member, Nathan Hale, would be glorified as a hero despite his failure.

After Nathan Hale’s ill-conceived solo spy mission, in 1777 George Washington tried to establish a spy network in and around New York City. The Continental Army commander in chief began by signing a contract with Nathaniel Sackett of Fishkill, who was a merchant in New York City, to gather intelligence.[3]

Washington selected a young officer, Yale College graduate Benjamin Tallmadge, a native of Setauket, Long Island, to serve as Sackett’s military contact. The first spy to gather information successfully on Long Island as part of the Sackett network was Maj. John Clark, a Pennsylvania lawyer who had volunteered as a lieutenant in 1775. Clark established a network of contacts and was active on Long Island during much of 1777. He sent his messages to Washington through Tallmadge, who was responsible for transporting Clark to the island from Connecticut.[4]

Clark’s intelligence was probably conveyed to Tallmadge by whaleboat captain Caleb Brewster, a friend and early classmate of Tallmadge who would become a captain in the Continental Army. When Clark, who operated in the Philadelphia area for most of the war, left the island, Washington needed another spy there or preferably a network of spies.[5]

Deciding his spymaster was better at developing successful espionage techniques than actually acquiring useful information, Washington terminated the arrangement with Sackett after two months.[6]

To his great relief, Washington received an unsolicited letter written on August 7, 1778—a day that could be considered the start of the Culper Spy Ring—from Lt. Brewster in Norwalk offering to gather intelligence on Long Island.[7] Washington instructed Brewster to “not spare any reasonable expense to come at early and true information.” Brewster wrote his first intelligence report on August 27, 1778.[8]

Washington realized he needed someone in the Continental Army to manage ongoing correspondence with Brewster. The general asked Brig.Gen. Charles Scott, commander of a Virginia brigade, to assemble a spy network, and detailed Tallmadge to assist. Scott put little effort or enthusiasm into the spy operation, so much of the work fell to Tallmadge.

Letters from Tallmadge and his childhood friend Abraham Woodhull, who would become the chief spy, demonstrate that by October 1778 the espionage operation was in full operation.[9]

With Scott’s approval, Tallmadge developed a list of codenames for the key players. Washington is believed to have invented the name for the network: Culper. It is thought to have been derived from the army commander’s surveying work in Culpeper County, Virginia, when he was seventeen. Tallmadge became John Bolton while Woodhull became Samuel Culper. Sometime in the fall of 1778, Woodhull began traveling to Manhattan and reporting verbally to Brewster what he observed.[10]

With the spies Scott had recruited personally providing little useful information compared to those brought together by Tallmadge, Scott decided to give up not only supervision of the intelligence-gathering but also the army. Washington then elevated Tallmadge, only twenty-four, to be his “director of military intelligence.”[11]

Operation of the Spy Ring

Afraid of traveling to New York after being stopped and questioned repeatedly by British sentries, Woodhull realized he needed to recruit someone else to spy there. His choice was Robert Townsend of Oyster Bay, purchasing agent in Manhattan for his prosperous merchant father, Samuel. To protect himself, Townsend adopted the alias of Culper Junior, as Woodhull was already Samuel Culper. Woodhull then became Culper Sr.[12]

To avoid areas where interception and capture were more likely, the agents and couriers carried intelligence reports from New York City across the East River, eastward on Long Island to Setauket, across Long Island Sound and then west along the Connecticut shore to Tallmadge and ultimately Washington north of the city or in New Jersey.

There are 193 known letters totaling 383 pages written by the Culper spies, Tallmadge, Washington and others.[13] The most recently discovered one—and the only surviving one between Tallmadge and Townsend—was found uncataloged in the archives of the Long Island Museum in Stony Brook last year.[14]

Improving the Spy Craft

Over the course of the conflict, the reports demonstrate an increasing level of spy craft sophistication. For the earliest letters, Tallmadge and Woodhull established a fairly simple process of hiding the identity of the members of the network by giving them codenames.

As the war wore on, security was increased by substituting numbers for people, places and things. The system devised by Woodhull and employed in his letter of April 10, 1779, used the figures 10 for New York and 20 for Setauket, for example.[15]

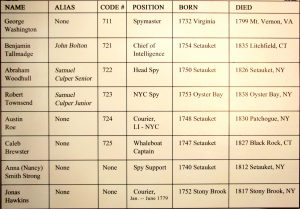

After inserting a few numerical ciphers in ten letters bound for New York and twenty going the other way, Tallmadge in July 1779 upgraded the system by preparing a “pocket dictionary” with an expanded code. The 710 words chosen were the ones most likely to be used, such as Congress, navy and Tory. Opposite each word was a number that would replace the word, such as “murder” being replaced by 387. Fifty-three proper nouns were given numbers ranging from 711 to 763. Thus Tallmadge became 721, Woodhull 722 and Townsend 723.[16]

The last—and best—added layer of security was using a special ink or “stain” invisible until treated with another solution. The ink was invented by amateur chemist James Jay, brother of John Jay, who became the first chief justice of the Supreme Court.[17] These espionage techniques employed by the Culper network were well-established tools of military spycraft, described in period military texts, but the Patriot spies and stain inventor James Jay developed their own variations.

Washington was excited at the prospect of improving the security of the spy ring, but it took him nearly six months, until December 1778, to receive a small initial supply of the solutions from Jay. The general did not have enough to provide any to the Culper spies until the following spring. In mid-April 1779, Woodhull finally received some stain and wrote that it “gives me great satisfaction.”[18]

In the initial phase of the Culper network, chief spy Abraham Woodhull traveled from Setauket to Manhattan every few weeks to collect information and then returned home to turn it over to Caleb Brewster for the trip across Long Island Sound. Even after Woodhull recruited Robert Townsend to gather intelligence in the city, he would still make trips occasionally to New York to compile information or serve as a courier connecting with Townsend. But when a courier was available, Woodhull was able to remain relatively safe in Setauket and rely on Townsend and the rider. The most frequent and dependable courier was Setauket tavern owner Austin Roe, who began making the dangerous trips about April 1779 and continued until early July 1782, when the Culper correspondence ceased.

There are several aspects of the Culper story that have generated much debate:

Use of a “Dead Drop”

According to Alexander Rose, former CIA case officer Kenneth Daigler and several other authors, Austin Roe would usually or at least sometimes leave the letters from Townsend in a secret location in one of Woodhull’s livestock fields in Setauket, where a “dead drop” box was hidden in the underbrush or buried. Woodhull would retrieve it later while attending to his cattle.

But Claire Bellerjeau, historian at the Raynham Hall Museum in Oyster Bay, Robert Townsend’s family home, who has spent decades studying the Culper ring, discounts the idea. “I haven’t seen any evidence of a dropbox” being used, she said, and there was no need for the spies in Setauket to have one because they could just hand off intelligence directly to each other.[19]

Anna Strong’s Clothesline

One of the best-known aspects of the Culper Spy Ring story is the purported role of Anna Strong’s clothesline. According to family tradition, Anna Smith Strong, a neighbor and close friend of Abraham Woodhull, would hang out laundry to dry in a pattern that indicated where he should rendezvous with Caleb Brewster. Morton Pennypacker and some more current historians treat the story as fact while others say there is no historical documentation for it.

Strong supposedly would hang a black petticoat on her clothesline to alert Woodhull, who lived across the bay, when Brewster had arrived from Connecticut to retrieve or drop off messages. She would add one to six white handkerchiefs to inform Woodhull in which of six coves Brewster would be waiting.

Pennypacker noted that he and other historians had spent years trying to track down information about how Woodhull knew where to find Brewster. “Finally a clue was found among the papers of the Floyd family and when this was compared with the Woodhull account book it was discovered that the signals were arranged by no less a personage than the wife of Judge Selah Strong,” Pennypacker wrote.[20] Strong family historian Kate Strong repeated the clothesline story in a chapter titled “In Defense of Nancy’s Clothesline” in a 1969 book. She said it was corroborated by scraps of paper, deeds, journals and letters in her possession, as well as documents she saw or was told about by Morton Pennypacker.

Many historians subsequently have repeated the clothesline story without skepticism. One version presented by former Central Intelligence Agency analyst Kenneth Daigler has Brewster looking at Strong’s clothesline through a telescope “from his base in Fairfield,” Connecticut.[21] That account ignores the long distance and curvature of the Earth that would thwart even modern telescopes. And it ignores the significant amount of land between the Sound and the Strong property. Brian Kilmeade wrote “the Strong estate, situated on a high bluff, would be visible to anyone passing by boat” on Long Island Sound.[22] But the Strong estate is not on a bluff by the Sound and its servants’ quarters, where the laundry would have been hung out to dry, are near the beach, not much higher than sea level. To his credit, Kilmeade does describe the clothesline story as “local legend.”

Most Long Island historians who have spent decades researching the Culper network view the clothesline story the same way. “I have read all of the Culper letters and there is no reference to Anna Strong’s clothesline,” Bellerjeau said. Beverly Tyler, historian for the Three Village Historical Society in Setauket, agreed: “The clothesline story is apocryphal; I treat it as folklore” although “she had to communicate with him in some way, whether it was the clothesline or some other regular method.”[23]

The Role of James Rivington

Historians disagree over the role, if any, of publisher James Rivington in the spy ring. Rivington operated a print shop in Manhattan, where he published a series of newspapers that demonstrated an extreme Loyalist point of view. In 1777 he began publishing the Royal Gazette at northeastern corner of Wall Street and Broadway. Rivington also operated two adjacent businesses, a coffeehouse and general store that sold stationery, which were frequented by British officers.[24]

Beyond those facts, things get iffy. Some authors have Robert Townsend working for Rivington as either a paid or volunteer reporter. These include Kilmeade, who offers that Townsend, who “had always had a knack for writing,” arranged to be hired by Rivington as a reporter in “a stroke of brilliance” because now he “had the perfect excuse for asking questions.”[25] Others go even further, elevating Townsend to being a co-owner of the newspaper and/or coffeehouse. Pennypacker and Alexander Rose have the two men jointly owning the coffeehouse, with Townsend spending time there chatting with British officers. But Pennypacker carries the story only so far. He believed Rivington knew nothing about Townsend’s spy activity. “That James Rivington ever imagined Robert Townsend to be in the service of George Washington there is no evidence to show,” the historian wrote. “In fact it is very unlikely. Rivington was not the type of man that Townsend would trust with that secret.”[26]

Kilmeade is the biggest outlier when it comes to Rivington’s espionage role: he portrays the publisher as a full-fledged Culper spy. He backs his contention by quoting a postwar letter from William Hooper, a North Carolina lawyer and signer of the Declaration of Independence, in which he stated that “there is now no longer any reason to conceal it that Rivington has been very useful to Gen. Washington by furnishing him with intelligence. The unusual confidence which the British placed in him owing in a great measure to his liberal abuse of the Americans gave him ample opportunities to obtain information which he has bountifully communicated to our friends.”[27]

Claire Bellerjeau, who has spent a lot of time picking apart the Townsend-Rivington connection theories, noted that Townsend operated a store on Hanover Square. “Rivington’s Gazette and his coffeehouse were right there on Hanover Square,” she said. “You see in Robert’s ledgers that he regularly bought Rivington’s Gazette. People might say that Rivington was the spy, but Robert clearly doesn’t think that Rivington is on his team because early on in 1779 in one of his spy letters he writes specifically to look in Rivington’s paper and you will see that somebody knows what we’re doing or has guessed very nearly. In Rivington’s Gazette he is writing that there are spies in New York and everybody should be on the lookout to turn them in. So Robert complains about Rivington. How is it that they are spies together? That just makes no sense.”[28]

Bellerjeau also noted there is no proof that Townsend and Rivington were partners in the coffeehouse. “There is zero evidence in his ledger books of any business connection with Rivington. The only thing we see is that he is buying his paper from Rivington. That’s it.”[29]

The authors who believe Townsend and Rivington had a business and/or espionage link point to the fact that Rivington is one of the names listed for substitution in the spy ring codebook. Kilmeade noted that “Rivington’s name was the last to appear among the Culper code monikers, 726, indicating that Townsend had recruited him soon after his own engagement, probably by the late summer of 1779, when the code was developed.”[30]

Bellerjeau countered that “we know that Rivington is one of the proper names in the Culper code. That makes you think he’s a spy, right? But you’ve got place names, people’s names on both sides of the conflict. Is Rivington’s name in there as a person or for the Gazette? As far as the Culpers are concerned, I think the word Rivington in the code meant the paper.” Because Tallmadge may have placed a guard to protect Rivington after the British left New York in 1783, Bellerjeau said, “Maybe Rivington had an outside deal with Washington and Tallmadge. Maybe he wasn’t part of the Culper Spy Ring but was doing other spy work for them.” It would make sense for security to keep intelligence operatives separated, she added.[31]

The Lady or Agent 355

Some recent books on the spy ring, including Brian Kilmeade’s 2013 bestseller, include the story of an Agent 355. She supposedly was a mysterious female Culper operative, even though a generic lady is mentioned only once in the letters. A coded letter from Abraham Woodhull to Washington dated August 15, 1779—a little over a month after Robert Townsend took over as chief spy in Manhattan from Woodhull—includes this sentence: “I intend to visit 727 [New York] before long and think by the assistance of a 355 [lady] of my acquaintance, shall be able to out wit them all.”[32]

That ambiguous reference has spawned a whole subgenre of the spy ring story. Morton Pennypacker suggested that not only was there a female Culper spy with the code number 355 but she also was the mistress of Townsend. And to make the story even more juicy, she was arrested, imprisoned on the infamous British prison hulk Jersey, gave birth to his illegitimate child onboard and then died.[33]

Other writers have taken up the story, with some putting her in the social circle of British spy John André. Still others, including Alexander Rose, declare that the 355 referred to was Anna Strong. But he does not turn her into a secret agent. Rose does have Strong—without documentation—accompanying Woodhull into Manhattan and masquerading as his wife to make his trip less suspicious to the British sentries.[34] That seems a stretch because she was older than Woodhull, and it would mean leaving her young children at home for at least two days.

Agent 355 is a recurring character in Kilmeade’s book. “One agent remains unidentified,” he wrote. “Though her name cannot be verified, and many details about her life are unclear, her presence and her courage undoubtedly made a difference.” With so little verified and so much unclear, it’s questionable how the Fox News cohost was able to conclude that she made such a difference. In Kilmeade’s telling, “she was somehow uniquely positioned to collect important secrets in a cunning and charming manner that would leave those she had duped completely unaware that they had just been ‘outwitted’ by a secret agent.”[35]

Kilmeade dismissed the possibility that Anna Strong is the 355 referred to in the letter, stating

“a much more likely contender would be a young woman living a fashionable life in New York . . . [who] almost certainly would have been attached to a prominent Loyalist family. . . . It is therefore possible that 355 was part of the glittering, giggling cluster of coquettes who flocked around the British spy John André as he moved around the city.”[36]

Kilmeade even has his Agent 355 helping to uncover Benedict Arnold’s treasonous plot to turn over West Point to the British. One also has to wonder why Kilmeade attaches his Agent 355 to Townsend in the city when the only mention of a lady in the letters is in connection with Woodhull. In Kilmeade’s version, as in Pennypacker’s, Agent 355 is imprisoned on the prison hulk Jersey. While Pennypacker has her dying there, Kilmeade gives her a chance of surviving the ordeal.[37]

Many current historians who have researched the spy ring scoff at the Agent 355 theories as wild speculation unsupported by facts. Daigler called it “a romantic myth” that was discredited in the mid-1990s.[38]

Setauket historian Beverly Tyler emphasized that there is only the one reference to a lady, in the August 15, 1779 letter. “That is it,” he said. “Everything else is made up—the whole business of Agent 355 and Robert Townsend.” Tyler is one of those who believes the lady referred to is Woodhull’s Setauket neighbor. “I’m fully convinced it was Anna Strong,” he said. “She had relatives who were Loyalists in New York City and she portrayed herself as a Loyalist. During the war, as far as we can tell—since we don’t know the details about the spies we have to make some assumptions—she accompanied Woodhull into New York city on occasion. Anna Strong was 355. She wasn’t Agent 355.” He said members of the spy ring “didn’t refer to each other as agents.” And the spies who did have code numbers were all numbered in the 700s. “Making up the word agent and tying it to the number 355 has no validity whatsoever.”[39]

Claire Bellerjeau also doubts there was anyone involved with the spy ring code-named Agent 355. But she conceded that “it’s quite possible that there was a woman who was an agent and a significant role player. I wouldn’t say that there is no agent, but she’s never mentioned again. I think people want to have good stories about women so I can understand that people want to weave a larger story out of this one reference. It’s the same thing with Anna Strong and her clothesline, even though there’s no real evidence behind that.”[40]

Bellerjeau disagrees with Tyler’s contention that the lady helping Woodhull would have been Anna Strong. She doesn’t believe it would be anyone in Setauket “because it’s so far out on the island and not that important a place. What special advantage could a person out in Setauket give you? The intelligence is about what’s going on in Manhattan.” As for Kilmeade’s speculation that the lady was a socialite in Major John André’s circle in the city, Bellerjeau said, “It’s certainly possible because you’re looking for somebody who’s in a particular position to outwit. But would a lady of high society be an acquaintance with Woodhull, a vegetable farmer from Setauket? It doesn’t seem likely.”[41]

Hercules Mulligan

Historians agree that New York City tailor Hercules Mulligan was a spy for George Washington. But they don’t agree on whether Mulligan was a member of the Culper ring, gathered intelligence independently or operated both ways.

The ambitious young man opened a tailoring and haberdashery business that catered to wealthy clients,including British officers stationed in the city after the occupation. He befriended Alexander Hamilton after he arrived from the West Indies in 1772. Hamilton lodged with Mulligan’s family while attending King’s College, and Mulligan helped convince Hamilton to support the Patriot cause. In March 1777, after Hamilton was appointed Washington’s aide-de-camp, he recommended to the general that Mulligan become a confidential correspondent in the city. Mulligan took full advantage of his access to British officers who were customers of his tailoring business and others billeted in his house.[42]

Mulligan proved valuable by informing Washington of British and Loyalist plots to capture or assassinate the general as well as planned enemy movements. Whether Mulligan was considered a member of the ring or not, he apparently began to cooperate at times with the Culper operatives in the summer of 1779. Woodhull mentioned in an August 12 letter that “an acquaintance of Hamiltons” had relayed information about British regiments embarking on transports.[43] That was about six weeks after Townsend, who had known Mulligan since childhood through his father, Samuel, began writing reports. According to Rose, Mulligan never wrote any known reports but provided information verbally to the Culper spies and via other routes to Washington.[44]

Daigler said there is documentation proving Mulligan did work with the ring on occasion. As evidence that he alsoran his own separate network, he cited a letter from Tallmadge to Washington. On May 8, 1780, the spy chief stated that he did not know what Mulligan was doing and asked Washington for any information on that subject that might affect his own intelligence activities.

Bellerjeau concluded that Mulligan was not part of the Culper Ring. “However, he and Robert knew each other, evidenced through two receipts,” she said. “Did they know that they were both gathering intelligence? It’s possible.”[45]

The details of how the Culper Spy Ring operated will continue to intrigue historians and history buffs, but absent new discoveries, many of the questions will remain unanswered.

[1]Brian Kilmeade and Don Yaeger, George Washington’s Secret Six: The Spy Ring That Saved the American Revolution (New York: Sentinel, 2013), xvii.

[2]Kenneth A. Daigler, Spies, Patriots, and Traitors: American Intelligence in the Revolutionary War (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2014), 95-96.

[3]Alexander Rose, Washington’s Spies: The Story of America’s First Spy Ring (New York: Bantam Books, 2006), 43.

[4]Ibid., 46-47; Daigler, Spies, Patriots, and Traitors, 103.

[5]Daigler, Spies, Patriots, and Traitors, 183; Morton Pennypacker, General Washington’s Spies on Long Island and in New York (Brooklyn: Long Island Historical Society, 1939), 11-16.

[6]Rose, Washington’s Spies, 50-51.

[9]Ibid., 48,71; Daigler, Spies, Patriots, and Traitors, 174; Richard F.Welch, GeneralWashington’s Commando: Benjamin Tallmadge in the Revolutionary War (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. Inc., 2014), 35.

[10]Rose, Washington’s Spies, 78, 87.

[12]Daigler, Spies, Patriots, and Traitors, 178-179.

[13]Interview with Raynham Hall Museum historian Claire Bellerjeau.

[14]Bill Bleyer, George Washington’s Long Island Spy Ring: A History and Tour Guide (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2021), 67.

[15]Pennypacker, General Washington’s Spies, 60, 209-10; Rose, Washington’s Spies, 114, 120.

[16]Daigler, Spies, Patriots, and Traitors, 182; Rose, Washington’s Spies, 114, 120-22.

[17]Rose, Washington’s Spies, 106-107.

[20]Kate Wheeler Strong, “In Defense of Nancy’s Clothesline,” True Tales from the Early Days of Long Island (Reprinted from the Long Island Forum, Amityville, N.Y.), 1969.

[21]Daigler, Spies, Patriots, and Traitors, 184-185.

[22]Kilmeade, George Washington’s Secret Six, 93.

[23]Interviews with Bellerjeau and Three Village Historical Society historian Beverly Tyler.

[24]Rose, Washington’s Spies, 151.

[25]Kilmeade, George Washington’s Secret Six, 84.

[26]Rose, Washington’s Spies, 151; Pennypacker, General Washington’s Spies, 13.

[27]Kilmeade, George Washington’s Secret Six, 107-108.

[30]Kilmeade, George Washington’s Secret Six, 106-107.

[32]Pennypacker, General Washington’s Spies, 252.

[34]Rose, Washington’s Spies, 173.

[35]Kilmeade, George Washington’s Secret Six, xviii.

[38]Daigler, Spies, Patriots, and Traitors, 189.

[42]Rose, Washington’s Spies, 225.

[43]Pennypacker, General Washington’s Spies, 252.

[44]Rose, Washington’s Spies, 226.

[45]Daigler, Spies, Patriots, and Traitors, 188; Bellerjeau interview.

21 Comments

Bill, thank you for a very interesting and provocative article. I certainly concur that “Turn” and Mr. Kilmeade’s historical fiction deserve careful reading and watching to ascertain facts verses opinion. But then we all suffer from that – even the dedicated and hard working local Historians in Setauket, with whom I have met and spoken.

Spying is a secret business and thus research into it is most difficult. I do wish to raise two issues: Rivington and my background.

Rivington’s association with Culper Jr., and Jr.’s association into the New York City British social environment, clearly places them in contact and since Rivington subsequently provided the British Naval Signal Plans to Allen McLane, I assume at some point he worked for the American side. How he was “recruited” or used unwittingly as a source is not known.

My former profession was that of a Case Officer, not an analyst and that effects my analysis of the Culper Ring as one would suspect.

I hope you enjoyed my book.

Excellent article. You have provided a very even handed look at the Culper Spy Ring which is long overdue. Most previous efforts make many assumptions about involvement that is based mostly on questionable interpretations posing as fact. Of course, the history of Culper is not helped by the various episodes of the tv series Turn.

Thanks for your comment Ken. I will be careful to get your job description correct going forward. [Ed. Note: The correction has been made.]

As I say in my book, the only known connections between Rivington and Townsend is that Townsend bought Rivington’s Gazette and they both worked on Hanover Square. Everything else I view as speculation.

I did enjoy your book, especially your analysis of the Culper codes.

I did have trouble with a few of your findings, as noted in this article and in the book, especially the idea that Tallmadge or anyone else could see Anna Strong’s clothesline from Connecticut, which would be physically impossible, and is evident when in Setauket.

Bill

Bill, in a previous life I taught American History and now my husband reads on the topic of the Revolutionary War, as well. While watching TURN, we spent countless hours searching for fact vs fiction after each episode, knowing much of it moves around, dates, characters, events, etc. I’ve read Kilmeade’s accounts as well…hmm?? Think I’ll put that book on a high shelf. I appreciate your article/analysis and hope someday to see a seminar in person with some of the folks mentioned.

Take care.

Lynda, I give online lectures on the subject frequently. You can see the schedule on the Long Island History Facebook page. It would be nice to do a session with multiple historians on the topic. Bill

Tnx for this brave undertaking, Bill. If Rivington did work for the Patriots, he had a great cover – his convincing portrayal as a copper-fastened Loyalist.

For instance, Patriot hard-ass Capt Isaac Sears described the printer as “infamous” in Nov 1775, when he led a 75-member gang that marched on his press shop with bayonets deployed and “within three-quarters of an hour brought off the principal part of his types.”

They didn’t like him and he didn’t like them much, judging from the news Rivington published.

Was it a clever ruse? Or is it possible that Rivington, after being put out of business so rudely, decided to play both sides against the middle going forward?

Tnx again.

Bill, this is the best summary and analysis of the Culper Ring I have read. As a historian who has studied the ring (and other rings and agents) for the past fifteen years, I am relieved you not only critiqued Kilmeade’s very flawed book, but also used your circle of informants – local historians like yourself – to gather the best evidence or refute when there there is no evidence. I hosted a Rev. War spy conference in Litchfield, Connecticut in 2018 at which Ken Daigler and I spoke, along with several others. I wish we had had you, too! Perhaps I will host another next year. Look forward to your new book, too. One small correction: Captain Caleb Brewster was never in the Continental Army. See Record of Service of Connecticut Men for proof. He was instead a captain after the war in command of the newly formed Revenue Cutter Service, precursor to the Coast Guard. Well done! Damien

Caleb Brewster was named a lieutenant in John Lamb’s 2d Continental Artillery in 1777. In the correspondence with Washington during the war, Brewster is always addressed or referred to by Washington as Lt. Brewster, his army rank. He was generally referred to by others as Captain Brewster because of his whaleboat activities. Anyone who commanded a whaleboat, at least in Connecticut, was typically called captain.

Sorry; my mistake. I have been working with earlier correspondence. Brewster was promoted later in the war (1780) to captain lieutenant in the Continental Army.

Caleb Brewster was an original member of the NY Society of the Cincinnati, as Captain-Lieutenant of the NY Artillery.

Bill, I have reread what I wrote and take responsibility for inaccurate use of the term “base.” From my former profession that term refers to a safe area from which to operate, rather than a specific physical site. While I tried hard to keep the terminology free from “professional” uses, that is one of a couple times I failed.

Damien, everything I have seen says that Caleb Brewster was a captain in the Continental Army on detached duty to operate whaleboats on Long Island Sound. I will check further based on your information. Thanks, Bill

Damien and Ken,

I thought it would be good for the three of us to share contact information because of our mutual interest in the spy ring. I can be reached at bi********@gm***.com. Bill

So then, what is the most accurate book written in this subject? Just curious

I would say mine-“George Washington’s Long Island Spy Ring“- is because I have reviewed and analyzed all the previous books. Bill

As noted by Selden, Brewster was in fact an officer in the Continental Army. Beverly Tyler, Historian for the Three Village Historical Society, one of my main sources for the book, confirmed that and supplied copies of letters to and from Washington‘s headquarters referring to Brewster as a lieutenant and also sent me copies of pay records for the army showing Brewster as a captain.

I,too, would like to know which book on the spy ring is the most accurate. Steve

I would love to see someone write about the Orange County, NY Woodhulls and Strongs, cousins to Abraham. Colonel Jesse Woodhull and his brother Captain Ebenezer Woodhull, who started the 1st Orange County militia, were brothers to the martyr General Nathaniel Woodhull. In 1778, their nephew, Major Nathaniel Strong, was murdered by Loyalist Claudius Smith when he couldn’t find Captain Ebenezer Woodhull at home (though he was never convicted of it – he was hung for robbery, etc. in Goshen shortly thereafter). Ebenezer was a horseman and transported/safeguarded messages throughout our area of Hudson Valley and even saw baggage safely through for Washington to Newburgh. Colonel Jesse Woodhull was constantly writing letters back and forth with Governor Clinton about the happenings here in Orange County, and he had Loyalist Fletcher Matthews for a brother-in-law (his brother was Loyalist mayor of NYC David Matthews). They have so many interesting little military tidbits that all weave a much larger and fascinating tale when you consider their connection to what was happening on/around Long Island. The Strongs, Woodhulls, and Brewsters married into each other’s families for generations to come here in Orange County and their influence can still be seen today. I think their story is fascinating and on-par with Abraham’s but no one really knows it. They’re quite overshadowed by General Nathaniel Woodhull’s well-known death, and then Abraham, thanks to TURN.

It does sound like a good book project for a historian in Orange County.

Bill,

I thoroughly enjoyed your well researched article – very glad to read that others may have seen the “poetic license” taken by the writers and producers of “TURN”.

As an avid Culper amateur historian, it is my humble opinion that “355” is Mary Smith [cousin of Anna Smith Strong] whom Woodhull was courting at the time he scripted the August 1779 note and who later became his wife. Mary was the “lady” [not a 701, “woman”] of the very influential Smith family of L.I. and would receive deference from the British sentries as she traveled to/from NY with Woodhull.

Whether Mary had been “read in” to Woodhull’s subterfuge, it is surely just speculation but, in order that she would shortly wed Mr. Woodhull, she likely had to know what he was doing.

Roy, It’s an interesting theory I haven’t heard before. I will share it with the local historians in Setauket and Oyster Bay who are my best experts. Bill