Following the campaign of 1776, New York City and environs were occupied by British forces. For the rest of the war, George Washington threatened, planned, and hoped to retake the city, although that did not happen until the British evacuation in 1783. New Jersey, particularly the eastern region of the state, became the front lines of the war, a no-man’s land between British-held Manhattan and the Continental Army to the west.

For the citizens of New Jersey, day-to-day life carried on in the midst of the war. Farmers, tradesmen, and merchants still needed to support themselves by their trades. Despite appeals to patriotism and the best intentions and efforts of numerous laws enacted by the New Jersey Assembly, commerce carried on between New Jersey and the British in New York in what was known as the “London Trade.” New York City was a major North American trading port, second only to Philadelphia, and its proximity provided a ready market for New Jersey goods, as well as access to consumer goods that were arriving at New York Harbor. Historians debate whether the illicit trade was the result of loyalty to the Crown, economic necessity, greed, or a combination of those or other factors.

By 1780, the New Jersey Assembly saw the need to take renewed action to curb the black market that was running rampant, and passed “An Act more effectually to prevent the Inhabitants of this State from trading with the Enemy, or going within their Lines, and for other Purposes therein mentioned,”[1] and for the first time included a provision that dealt with shopkeepers.

Section 18 of the Act required

if any Person or Persons inhabiting any of the Counties adjoining the Enemy’s lines offer for Sale either by Wholesale or Retail any Goods, Wares or Merchandise, other than the Produce or Manufacture of this State or of the neighboring States, without first obtaining a License for that Purpose from the Justices of the Court of Quarter Sessions held in and for the County where such Goods, Wares and Merchandise are proposed to be sold, the said Person or Persons so offending shall forfeit and pay for every such Offence the Sum of Six Poundslawful Money of this State, with costs of suit[2]

The New Jersey counties which bordered the British lines in New York City, and to which this Act seemingly was targeted, included the entire northeast corner of the state: Bergen, Essex, Middlesex, and Monmouth Counties.

Section 18 went on to explain the license application procedure:

any Person proposing to open a Shop or Store hereafter in the respective Counties on the said Lines, are directed to apply to the Justices of the Court as aforesaid . . . for a license for that Purpose; and the said Justices are hereby authorized, when it shall appear to them proper and necessary, to grant such License, to any person applying for the same, who may or shall produce a Petition to the said Court, signed by at least fifteen reputable and well-affected Freeholders in the same County, certifying the Applicant to be of good Repute, and also well-affected to the Government of this State[3]

The Courts of Quarter Sessions convened four times a year presided over by Justices of the Peace, heard minor civil and criminal cases, and also administered local affairs such as issuing tavern and ferry licenses, fixing and collecting taxes and laying out roads.[4] In modern parlance, the Courts of Quarter Sessions functioned as a combination of small claims court, municipal court and local clerk.

The Act went on to state that operating a store or shop without the required license would subject the violator to not only fines and costs of suit, but also seizure of the goods, wares or merchandise offered for sale.[5]Once seized, the contraband goods would be sold at public sale and after costs were deducted, “the residue shall be divided among the persons seizing the same, in proportion to their pay, if on military duty.”[6]

Shopkeepers did comply with the law. Some petitions are very simple and succinct; others provide more details about the applicants, their circumstances, and even what goods were offered being for sale.

For example, the petition of Jacob Smith of Acquackanonck reads:

To the Honbl’e Court of Quarter Sessions held at NewArk in the County of Essex April Term 1781

We the Subscribers Freeholders and Inhabitants of the Township of Acquackenough in said County, request the Honb’le Court that a License for keeping an open store or Shop may be granted for Mr. Jacob Smith a Freeholder and Inhabitant of said Township living near the Little Falls agreeable to an Act of Assembly passed for that purpose He having formerly kept a store, and being well affected and a Firm friend to the American States.

And your petitioners as in duty bound shall ever pray[7]

A somewhat more detailed petition was submitted by Francis Post, also of Acquackanonck, mentioning his flight from New York and his loyalty to the Whig cause:

To the Hon’ble Court of Common Pleas [illegible] at Newark in & for the County of Essex on the fourth Tuesday of June 1781

Whereas the Mr. [illegible] Francis Post a Worthy Citizen of New York was obliged to become a refugee & inhabitant among us in the Township of Acquackanonck in this County [illegible] Now a fine [illegible] friend to the Liberties of America & its Perpetual Independence in now obliged to support himself & family with the small Profits of an honest Trade of commerce with the Inhabitants of New York

We the Subscribers freeholders in the Township Humbly Pray that a License may be Granted Unto him for keeping an open shop according to the Law of the Legislature of this State in that Gov [illegible] made & provide & Yours Deliberation as in Duty Bound shall Ever Pray[8]

William Nixon, also of Acquackanonck, submitted an even more detailed petition:

To the Honorable Court of Quarter Sessions of the Peace to be held at Newark in the County of Essex, State of New Jersey on the second Tuesday in January First

The Petition of William Nixon of Gotham, in the Precinct of Aquackanack and of us the Subscribers

Humbly Sheweth that whereas the Said William Nixon late an Inhabitant of the City of New York, but on the Invasion of the Country by the Enemy did not think it his duty to stay with them in the City, nor in their Lines, lest his native Country should consider him as Abeting, Aiding or Countenancing them in their unjust and Arbitrary Measures of Enslaving or Subduing the Country for which other reasons he left his Native place and his property (which was to him very Considerable) and came in to this Country, And what was an additional Calamity to him was that a Dwelling House, Store and other Buildings which was all new, were intirely consumed by the dreadful Fire which happened shortly after the Enemy took possession of the City, and as the said William Nixon has a large Family of Seven Children and has hitherto cheerfully contributed his proportion towards the support of his Country, and as the said William Nixon has even since his abode in the Country endeavors to support his Character as a Reputable fellow Citizen and an Honest man

Therefore the said William Nixon and we the Subscribers do Humbly pray that a license may be granted to the said William Nixon to keep an open shop at Gotham, near Aquacanack Bridge and in the County of Essex aforesaid, as Pursuant to an act Intitled an Act more Effectively to prevent the Inhabitants of the State from Trading with the Enemy, or going within their Lines and for other purposes therein mentioned and we the Subscribers do hereby Certify that the said William Nixon is a person of good Repute, and also sincerely and well affected to the Government of these States as at Present established under the Authority of the People

And Your Petitioners as in duty bound shall every pray

Gotham, near Aquacanack Bridge

January 8th 1781[9]

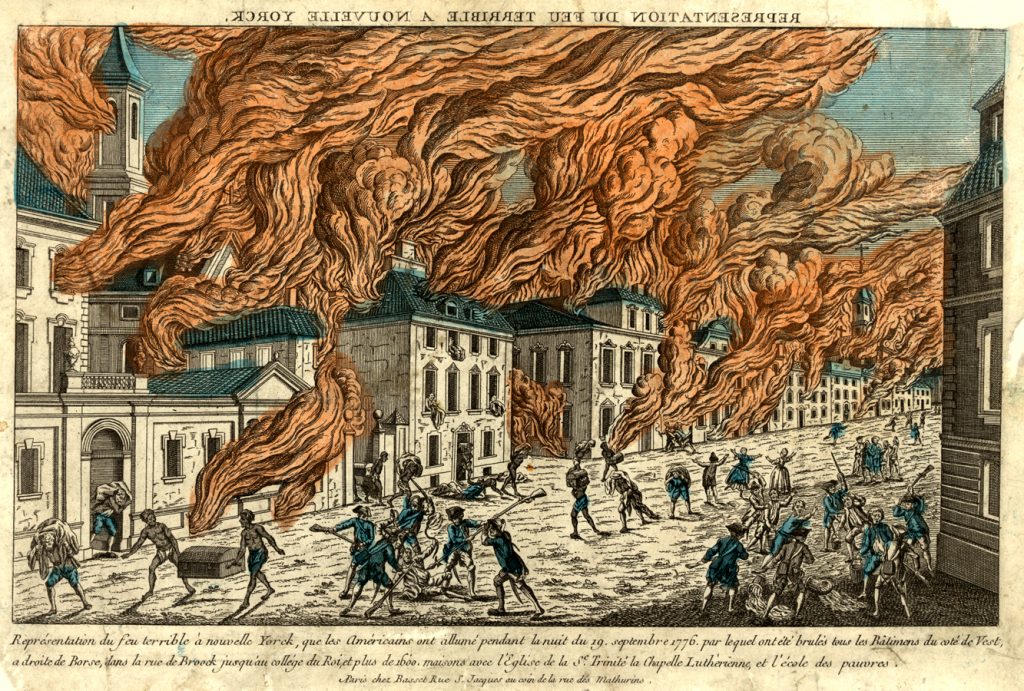

Nixon’s petition not only made a very strong case for his loyalty to the American cause, but also the losses he suffered in the fire that tore through lower Manhattan in September 1776. On September 20–21, 1776, only a few days after the British occupied Manhattan, a fire broke out in the lower part of city. It is estimated that close to one thousand buildings were destroyed; essentially the entire south-western tip of Manhattan Island was burned to the ground.[10] The cause of the fire has never been determined, and both sides blamed the other for the conflagration.

Many of the petitions refer to keeping “an open shop,” which was a term of art, meaning a business that was open to the public (as opposed to a shop that limited its clientele and operated by commission only) with a permanent physical location (as opposed to a market stall seller or peddler).[11]

Review of the petitions also gives an idea of what types of consumer goods were available for purchase. Sarah Camp, of Acquackanonck, sought to sell imported goods from her home:

The Petition of the Widow Sarah Camp and of us the Subscribers

Humbly Sheweth that whereas the Widow Camp is owing to the extreme hardship of the Times Considerably reduced, and has an expansive Family to support, and at present is in no way of business to secure their situation any more agreeable beg therefore a license may be granted her the Widow Camp to keep an open shop & store at the house where she now lives, for the sale of West Indies and European Goods, agreeable to an Act of the Legislature of this State. Of your petitioners are in Duty Bound will ever Pray

Sarah Camp

New Ark April 8th 1781[12]

Enos Jacques, of New Brunswick, sold rum, sugar and salt and sought a license to continue such sales:

Jan’y 16th 1781

To the Honorable Court of Quarter Sessions now sitting at New Brunswick. the humble petition of Enos Jacques sheweth that your petitioner is a person well effected to States and has for some time past sold by retail Rum Sugar and Salt and has now a considerable Quantity on hand would be glad of a license from the Honorable Court to retail goods whereby he may not only be in a way of helping himself but the Public also.[13]

Licenses were issued in due course and commerce carried on. The licenses themselves were fairly bland legal documents; the one granted to an Acquackanonck shopkeeper is quite typical:

Essex County

Court of Sessions

Of the Term of April Dom. 1781

Essex County for the Justice of the Peace for the County of Essex gives of [illegible] Licenses, admits and allows Garrett H. Garritse to keep an open shop or store at [blank] in the County of Essex,[illegible] in all things expecting a J[illegible] in the behaving himself as the Law directs—Given under the Seal of the Court at Newark the tenth day of April, in the Year of our Lord, one thousand seven hundred and Eighty one

By Order of the Court

s/Robt Ogden[14]

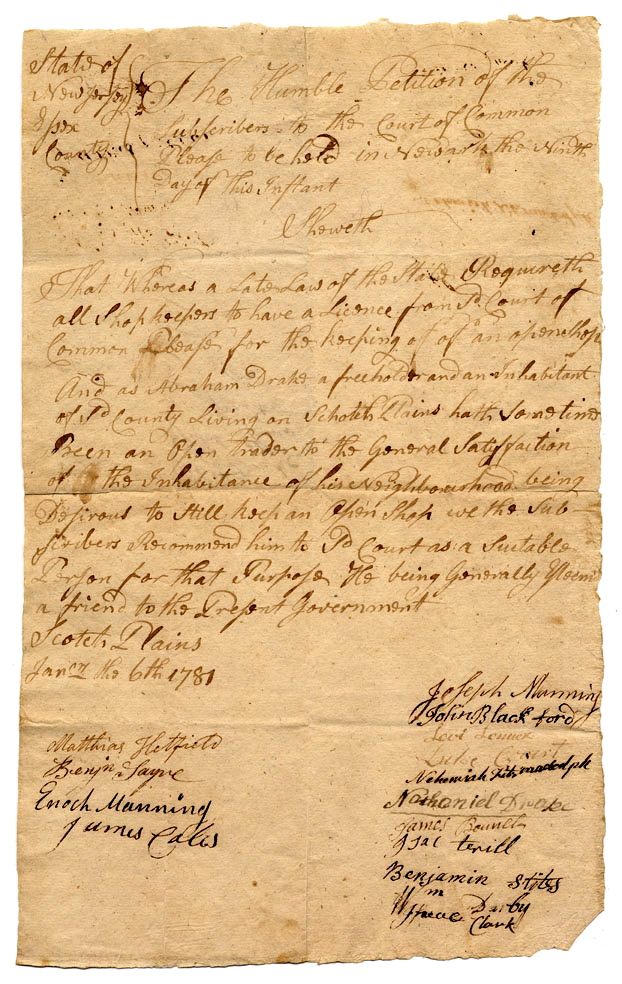

Abraham Drake, of Scotch Plains, submitted a petition dated January 6, 1781:

That Whereas a Late Law of the State Requireth all Shops & stores to have a license from the Court of Common Pleas for the keeping of an open shop

And as Abraham Drake a freeholder and inhabitant of S[ai]d County living on Scotch Plains hath some time Been an open Trader to the General Satisfaction of the Inhabitants of his Neighborhood being desired to still keep an Open Shop we the Subscribers Recommend him to the Court as a Suitable Person for that Purpose He being generally known a friend to the Present Government.

Scotch Plains

Jan’ Ye 6th 1781[15]

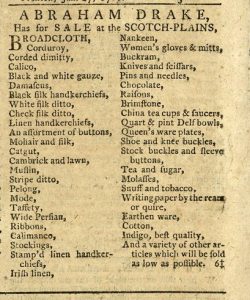

Drake’s petition was apparently successful, because the New Jersey Gazette edition of February 14, 1781 contained an advertisement for his shop, listing all sorts of goods for sale: white, black and check silk and stamped linen handkerchiefs, a variety of fabrics, China teacups and saucers, Delf bowls, snuff, tobacco, and “a variety of other articles which will be sold as low as possible.”[16]

The petitions of these shopkeepers give valuable insight to the conditions in New Jersey in the later days of the Revolution. Four years after independence was declared and the British seized and held Manhattan and its environs, some of New Jersey’s citizens were still trading with the enemy, and the Assembly was still trying to stop it. These petitions show the impact that the war had on New York’s Whigs who had to flee Manhattan because of their support for the Revolution. And they show that even in the midst of a war, a wide variety of consumer goods, many of them imported, were available for purchase.

[1]Acts of the Fifth General Assembly of the State of New Jersey, Chapter 5, 11-20, www.njlaw.rutgers.edu/cgi-bin/diglib.cgi?collect=njleg&file=005&page=00001

[2]Ibid., 18-19. Italics in the original.

[4]Erwin C. Surrency, “The Courts in the American Colonies,” The American Journal of Legal History 11, no. 3 (1967): 253-76.

[5]Acts of the Fifth General Assembly of the State of New Jersey, Chapter 5, 19.

[7]State of New Jersey Department of State, New Jersey State Archives, www.nj.gov/state/archives/cesqu001.html.

[10]Barnet Schecter, The Battle for New York(New York: Walker & Company, 2002), 204-208.

[11]Claire Walsh, “Stall, Bulks, Shops and Long-Term Change in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century England,” The Landscape of Consumption, J. H. Furnee, C. Lesger, eds. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 37-38.

[12]State of New Jersey Department of State, New Jersey State Archives.

Recent Articles

That Audacious Paper: Jonathan Lind and Thomas Hutchinson Answer the Declaration of Independence

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Recent Comments

"Eleven Patriot Company Commanders..."

Was William Harris of Culpeper in the Battle of Great Bridge?

"The House at Penny..."

This is very interesting, Katie. I wasn't aware of any skirmishes in...

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...