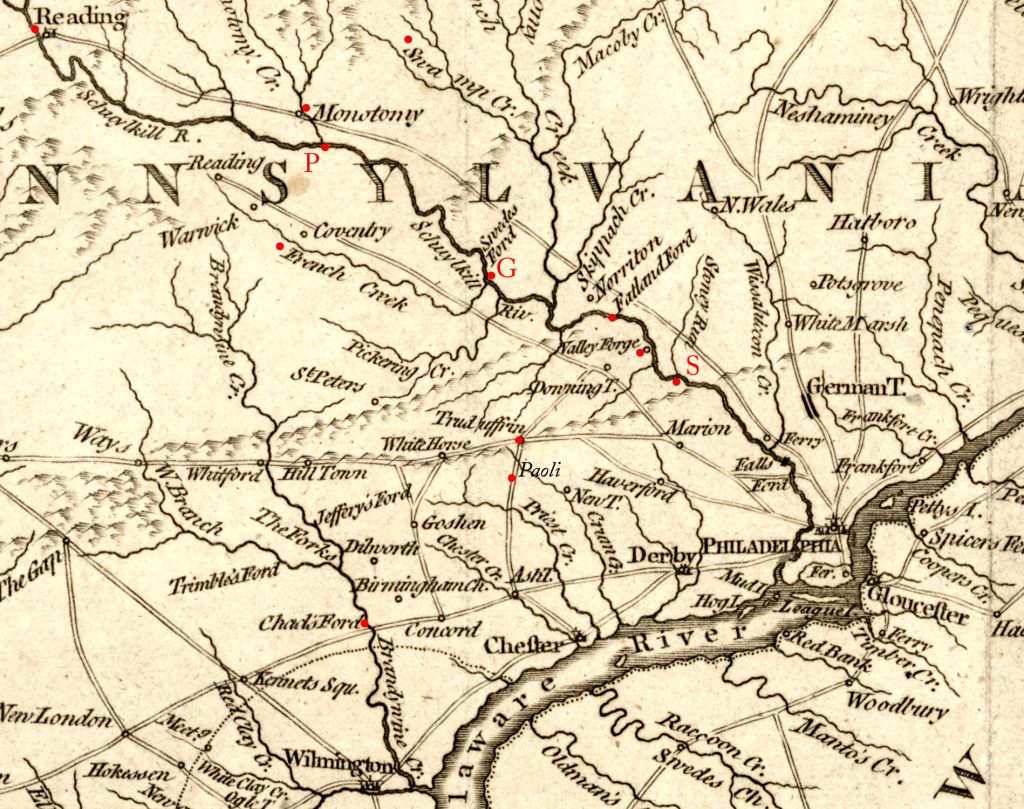

By noon on Saturday, September 20, 1777, Gen. William Howe watched his window of opportunity to cross the shallowing upper fords of the Philadelphia sector of the Schuylkill River slam shut upon his 14,000-man army. Gen. George Washington and 9,000 Continentals and militia blocked the seven closest river crossings to Howe’s forces which had been encamped along the Swede’s Ford Road at Tredyffrin on the opposite side waiting for the water levels to drop for safe passage of supply wagons and artillery. Meanwhile, 1,500 Continentals and an equal number of Maryland militia sandwiched Howe’s army from the southwest. At stake for Howe was the road to Philadelphia, a sixteen to twenty-two mile southerly avenue depending on where he crossed the Schuylkill. Equally important was to regain an unobstructed supply line to adequately feed, clothe and arm his substantial force.

Washington had clearly checked his opponent. Although suffering more than 2,000 losses in ten days from Brandywine battle casualties, skirmish losses, illness, and desertion, Washington now had the opportunity to create a rare moment of desperation upon his adversary which could lead to a costly decision. Merely thirty hours and thirty miles earlier, His Excellency had departed Reading Furnace with the bulk of his army and crossed the chest-high waters of Parker’s Ford, twenty-two twisting miles upriver from Swede’s, and proceeded to march them well past midnight and rested them only two hours before moving on—not to Swede’s Ford which was already defended by Pennsylvania militia and Continental artillery—but to Fatland Ford five miles west from Swede’s where his intelligence system had notified him that Howe would cross his army.[1]

Seemingly, three options confronted Howe beginning at noon that Saturday: 1) battle the Americans to clear one of those seven fords or ferries; 2) clandestinely reposition his army for a thrust toward a more weakly protected ford above or below those seven crossings, or 3) abandon the Schuylkill altogether and pull back to his supply base which was in the process of transferring from Head of Elk, Maryland, up the Delaware River to Wilmington (his capture of the supply depot at Valley Forge bought him extra time before he needed to consider this particular option). Trapped with choices to Do-or-Die or a Do-and-Die, General Howe faced either the humiliation of pulling back and starting over, or the tragedy of spilling buckets of British blood to secure a toe-hold on the Philadelphia side of the Schuylkill.

Howe chose none of those options; he did not need to. Three days to the hour after Washington locked him in inertia, this checkmate dramatically reversed. At 1:00 p.m. on Tuesday, September 23, General Howe completed the fording of his entire army—including his massive baggage train of several hundred wagons—at four of those seven targeted crossing points, all of them above Swede’s Ford, the vast majority funneling through Fatland Ford. He did this unopposed and unobstructed. Thirteen hours were consumed from start to finish but by the time Howe’s men began their advance toward Philadelphia on the eastern side of the Schuylkill in the early afternoon he had not lost a single soldier to opposing gunfire. As an added bonus, Howe captured six cannon and more supplies at Swede’s Ford by surprising it from the northwest and inducing the American defense guarding it to flee to safety. A dozen miles northwest of the British army, a frustrated and helpless General Washington could do nothing to stop him. Three days later, Howe captured Philadelphia.

How did this happen? Philadelphia Campaign historiography points to an unforeseen fourth option chosen by Howe. It describes an intentionally false move by the British westward toward the upper Schuylkill town of Reading (not to be confused with Reading Furnace on Howe’s side of the river) which housed massive stores of army supplies for the Continentals. This feint, as described by campaign historians, induced an already-wary Washington to pull up his defenses from the Schuylkill fords and direct them westward to protect Reading. “The feint succeeded admirably,” reasoned one, “for it got [Howe] across the Schuylkill with no opposition . . . Howe’s maneuver was brilliant.”[2] At least seven other writers echoed that conclusion.

Only a couple of contemporary sources describe this feint, both from the American perspective. George Washington alluded to it a few hours after Howe’s completed crossing when he wrote, “Genl Howe by various Manuvres & marching high up the Schuylkill, as if he meant to turn our right Flank found means by countermarching to pass the River last night several miles below us.”[3] Brig.Gen. Henry Knox elaborated the following day when he recalled that on Sunday, September 21, “the enemy made a most rapid march of ten or twelve miles to our right: this obliged us to follow them. They kindled large fires and in the next night marched as rapidly back and crossed at a place where we had few guards.”[4] Thus, both American generals defined the British feint as a planned westward march followed by an eastward countermarch on the opposite side of the Schuylkill River from the American defense.

Notwithstanding the allusion of a September 21 feigning maneuver described by Washington and Knox, British and German writers did not describe this as a brilliant maneuver; they never considered the maneuver at all. Diaries, journals and letters of officers in Howe’s army are replete with detailed accounts of fording of the Schuylkill. Not one of them even alluded to a feint and a subsequent countermove to cross the river. General Howe’s very devoted aide de camp, Friederick von Munchhausen, recorded no fewer than fifteen descriptive paragraphs to British movements, positions, and American activity related to the several potential river crossings from September 21 to 23 but he never mentioned or even hinted at a feint.

The single greatest beneficiary of Howe’s “brilliant” maneuver was General Howe’s reputation. In a tense and expensive campaign rife with minor setbacks and points of controversy, one could only imagine that when the commander in chief of the Crown Forces in North America composed his chronological summary of the campaign to George Germain, the day he hoodwinked George Washington so completely and successfully would become one of the highlights of this report, written a mere seventeen days later. Howe’s entries for September 21-23 certainly did not lack details, but they omitted any mention of a skillful maneuver designed to outfox George Washington. Howe’s detailed a spread-out occupation of the river banks with subsequent crossings on both flanks:

On the 21st the [British] army moved by Valley Forge, and encamped upon the banks of the Schuylkill, extending from Fat Land-ford to French-creek. The enemy upon this movement quitted their position, and marched toward Pottsgrove in the evening of this day.

On the 22d the grenadiers and light infantry of the guards crossed over in the afternoon at Fat Land-ford to take post, and the chausseurs crossing soon after at Gordon’s-ford, opposite to the left of the line, took post there also. The army was put in movement at midnight, the van-guard being led by Lord Cornwallis, and the whole crossed the river at Fat land-ford without opposition. General Grant, who commanded the rear-guard with the baggage, passed the river before two o’clock in the afternoon, and the army encamped on the 23d with its left to the Schuylkill, and the right upon the Monatomy road, having Stony Run in front.[5]

General Howe’s detailed description never details, mentions, or alludes to a feint. Other British and Hessian accounts dovetail well with Howe’s account, although adding two more crossing points between Howe’s two established posts. Thus, when Howe passively mentioned that “the army was put in movement at midnight,” he was not describing a midnight feint—who would see this to be fooled?—but rather a massive organized crossing of the Schuylkill which required between thirteen and fourteen hours to complete. In this case the absence of eyewitness evidence is evidence for absence. There was no designed feint on September 21 by Gen. William Howe.

One British diarist described a completely different feint on a different day. On Monday, September 22, Capt. John Montresor told his journal, “At 5 this morning the Hessian Grenadiers passed the Schuylkill at Gordon’s Ford under fire of [American] artillery and small arms and returned back being intended as a feint.”[6] Although generally a reliable campaign documentarian, Montresor appears to have missed the mark on this one. That he entered this sentence toward the end of the day’s chronological entry rather than at the start of it suggests that Montresor was relaying hearsay rather than documenting a witnessed order or event. This hearsay proved erroneous; Crown Forces did indeed cross the Schuylkill at Gordon’s Ford “at 5,” but this occurred at 5 p.m. and not “in the morning.” If Montresor’s account was indeed accurate and described a morning maneuver, this over-and-back, pre-dawn movement would have commenced twenty hours before the British mass movement at midnight. Whenever it may have occurred, this feint would have been counterproductive as it would have lured an American army back to the fords it had abandoned on September 21.

If not a feint, what happened on September 21 to give Howe an open and uncontested half-day crossing at Fatland Ford? Howe’s aide postulated that Washington’s response to the devastation of Gen. Anthony Wayne’s two brigades near Paoli Tavern at midnight of September 20-21 opened the door for Howe to operate. Although Howe sent a trumpeter before sunrise on Sunday, September 21, to deliver a request for a surgeon to care for “some wounded Officers & Men of your Army,” Washington’s response clearly indicated that he did not receive Howe’s request until Saturday’s evening hours, a perplexing miscarry. As Howe noted in his report to Germain, Washington “quitted his position” before this; an American soldier confirmed this when he noted that the Continentals pulled back five miles from their ford defense to the Philadelphia-Reading Road at 3:00 p.m. General Wayne’s preliminary and nondescript Paoli report—“I can’t as yet ascertain our Loss”—may have reached Washington before Howe’s request, but it had to travel thirty-one miles and cross the Schuylkill to get to him. Thus Washington’s first knowledge of the outlines of Wayne’s defeat could not have been received before late afternoon or early evening; by this time he had already made a fateful decision entirely independent of his first knowledge of the “Paoli Massacre.”[7]

The fiasco at Paoli in the first hour notwithstanding, what happened during the rest of that Sunday ranks September 21 as the nadir of the campaign to date for the Americans—exceeding even their loss at the Brandywine battlefield. Washington departed his Thompson Tavern headquarters in the morning to inspect his ford defenses. Since the freshets produced by the eighteen-hour storm of Tuesday at noon through Wednesday morning, dry, cool and windy weather had taken over the region both day and night over the next four days. Tench Tilghman, Washington’s volunteer aide de camp, expressed what the rest of headquarters had realized by Sunday morning—the “River has fallen and is fordable at almost any place, the enemy can have no reason to delay passing much longer.” At about the same time Washington approached the Schuylkill crossings from the north, General Howe had conducted a mass redeployment of his army from the Swede’s Ford road to the south to the banks of the Schuylkill. By early afternoon, much of Howe’s army covered the east-west road running five miles between Fatland Ford and Gordon’s Ford. By doing so, Howe had prepared to challenge one or more of the first five fords and ferry sites above Swede’s Ford, all of them currently opposed by Washington’s army.[8]

With twenty-two miles of river opposed by American forces from Swede’s to Parker’s fords, the mass approach of Howe’s army early on Saturday afternoon to challenge a seven-mile middle segment (from Fatland to Gordon’s fords) certainly was cause for Washington to alert his army and prepare to stiffen his defense. Washington, however, literally ordered his forces in the opposite direction. At 3:00 p.m. the infantry guarding the fords downriver from Sullivan’s left flank pulled back five miles northwestward to the Philadelphia-Reading Road. There they waited for their next orders. Washington was planning to shift them toward Reading. Five miles in that direction, the citizenry near Trappe, a community six miles east of Parker’s Ford on Washington’s side of the river, was advised that a battle may be fought there and that the return of the American army was expected.[10]

Washington fulfilled those expectations by abandoning all ten crossings of the Schuylkill. At 8:00 p.m. a dispatch left headquarters to be delivered to General Sullivan. The message informed him “that this Army is about to March up the Road by which we came down & is not to Halt untill we get beyond that Road which leads from Parker’s Ford into the Reading Road, beyond the Trapp.” Washington ordered Sullivan to parallel the army’s westward advance, keeping between them and the river, and to merely leave a few soldiers at each of the six fords he had been guarding as observational posts rather than bodies of resistance.[11]

Washington and nearly three dozen headquarters personnel departed Thompson’s Tavern as the army marched away from the region at 9:00 p.m. At midnight the vanguard of his army had marched past Trappe and continued until 3:00 a.m., ostensibly to assure Washington would not be flanked at Parker’s Ford or above it.[12] Washington’s admitted a month later that the Schuylkill town of Reading was his chief concern. It stood on Washington’s side of the river, thirty-five road miles from Swede’s Ford. In addition to housing the several hundred Hessian prisoners from the Battle of Trenton, Reading was the largest depot of military supplies for the Americans. As Washington later explained, the loss of Reading “must have proved our Ruin.”[13]

Washington’s exaggerated commitment to protect Reading ruined his chances of preventing Howe from crossing the Schuylkill. Furthermore, his and General Knox’s assertion that their abandonment of the river defenses was in response to Howe’s “most rapid march of ten or twelve miles to our right” which “obliged us to follow them” has no merit. Howe’s mass deployment by early Sunday afternoon ended with his left (western) flank anchored on French Creek, a meandering tributary which emptied into the Schuylkill at Gordon’s Ford. This westernmost position of Howe was already opposed by Sullivan’s troops. Howe did not conduct any march to flank Washington beyond this point; in fact, Sullivan’s complete deployment to Parker’s Ford outflanked Howe by several miles.[14]

Washington’s catastrophic decision and movements from the afternoon and evening of September 21 must have been conducted under the perception of a British rapid movement, even though no such movement ever occurred. Without Wayne or Gen. William Smallwood available to confront Howe’s shift of direction—and not yet aware of Wayne’s defeat near Paoli—Washington relied upon his cavalry (“the accounts of our reconnoitering parties”) across the river for intelligence gathering, as well as residents along the river. “This [movement of the enemy] induced me to believe that they had two objects in view, one to get round the right of the Army, the other perhaps to detach parties to Reading,” Washington reasoned two days later.[15]

Washington had the opportunity to correct his mistake on Monday morning, September 22, once he learned that Howe’s army was not further up the river from Gordon’s Ford. Instead, the American army continued to shift westward towards Reading—abandoning the fords that they so effectively reached and covered two days earlier. (During this movement, according to General Knox, they received their first intelligence of how roughly General Wayne’s brigades had been handled at Paoli.) Washington continued to insist that Howe was marching up the roads on the opposite side of the river. Writing to the colonel of the 1st Virginia State Regiment to reinforce the Continentals, Washington revealed, “I think it proper to inform you that we are at present here and are moving up the Country towards Reading as the Enemy are moving that way upon the West Side of Schuylkill.”[16]

From opposite the Schuylkill, General Howe noted how far Washington was moving towards Reading. The Crown Forces had barely budged since aligning along the river from Gordon’s Ford to Fatland Ford the previous day. Howe by this time had become aware that Washington “quitted his position.” The British commander had sent a scouting party southward, away from the river, which would not have been detected by the Americans. Perhaps in his first effort to ruse Washington, Howe ordered a small force to advance westward from his French Creek flank after the southward scouting mission commenced, but they proceeded only two miles toward Reading—not even halfway to Parker’s Ford—before returning.[17] Given that the American army tarried northwest of the turnaround point, this non-threatening movement did not induce a reaction. This westward maneuver may have been designed as a simple, short scouting mission rather than a feint.

Washington’s overreaction on Sunday, September 21, gifted Howe with four fords and two ferries, virtually abandoned directly in front of him, all upriver from Swede’s Ford. Ninety minutes before sunset that Monday, General Howe tested those waters. Nearly 300 Hessians successfully crossed the Schuylkill at Gordon’s Ford, three feet deep. By the time Washington received this news, the Continental army was even further away from those fords, having marched to grounds fourteen miles by roads to Flatland Ford and twelve miles from Gordon’s Ford. Although his response time was over three hours if he acted immediately, he could still get his army to the fords in time to disrupt part of Howe’s crossing, or at least separate him from his several hundred baggage wagons. But Washington never pulled that trigger. Counter intelligence incorrectly contradicted the report that Howe was crossing the river. Washington dispatched hand-picked troops to gather more intelligence but did nothing else.[18]

This vacillation cost Washington the nation’s capital. Howe completely crossed his army at the two fords—and perhaps two others between them—unopposed, the main crossing at Fatland Ford beginning at midnight. Howe’s baggage did not even begin to ford until the forenoon of Wednesday, September 23, and didn’t roll onto dry roads on the Philadelphia side of the river until after 1:00 p.m.[19] By this time Washington was even further away as his army moved their camp northwest of Swamp Creek, eighteen miles from the Crown Forces, too far away to contest Howe’s entry into Philadelphia three days later.

Historiography has clung to a planned maneuver by Howe that fooled George Washington into pulling away from his contested crossing points on the Schuylkill. Although this feint never happened, Washington’s incredibly exaggerated response to his own misperception of Howe threatening to be twice as far up the Schuylkill as he actually was had accomplished a goal Howe could never have expected had he actually planned this phantom feint. By allowing Howe more than thirteen hours to start and complete an unopposed crossing over a seemingly impenetrable barrier, Washington committed an error with far greater implications than anything he did or did not do on the Brandywine battlefield a dozen days earlier. Thus, the decisions and actions on the Schuylkill from September 21-23, 1777 should be considered a major turning point—albeit an unheralded one—of the Philadelphia Campaign.

[1]Henry Knox diary, September 19, 1777, Henry Knox Papers, Gilder Lehrman Institute, New York, NY.

[2]John F. Reed, Campaign to Valley Forge: July 1, 1777-December 19, 1777 (Philadelphia, Pa.:Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania, 1965), 181.

[3]George Washington to Israel Putnam, September 23, 1777, in Philander D. Chase, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2004)11: 305 (PGW).

[4]Henry Knox to his wife, September 24, 1777, in Francis S. Drake, Life and Correspondences of Henry Knox, Major-General in the American Revolutionary Army (Boston: Samuel G. Drake; 1873), 50.

[5]William Howe to George Germain, October 10, 1777, in The Parliamentary Register, vol. 10 (London: Wilson and Co. Wild Court, 1802), 429-30.

[6]G. D. Scull, ed., “The Montresor Journals,” Collections of the New York Historical Society, vol. 14 (1881), 456-57.

[7]Ernst Kipping and Samuel Stelle Smith, eds., At General Howe’s Side 1776-1778: The diary of William Howe’s aide de camp, Captain Friedrich von Muenchhausen (Monmouth Beach, NJ: Philip Freneau Press, 1974), 34-35; Howe to Washington, September 21, 1777, PGW, 11: 283. The unrefuted evidence of the miscarried message can be found in Washington’s response: “Your Favor of this date was received this Evening . . .” (See Washington to Howe, September 21, 1777 PGW, 11: 284.); Anthony Wayne to Washington, September 21, 1777, PGW, 11: 286.

[8]Howe to Germain, October 10, 1777, Parliamentary Register, 10: 429; Scull, “The Montresor Journals,” 456; Kipping and Smith, At General Howe’s Side, 34-35; Tench Tilghman to Alexander McDougall, September 21, 1777, PGW, 11: 293.

[9]Washington to John Sullivan, September 20, 1777, PGW, 11: 277; “Fords Across the Schuylkill River in 1777,” in Scull, “The Montresor Journals,” 419.

[10]“Diary of Lieutenant James McMichael,”Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (16), 152; The journals of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, trans. Theodore G. Tappert and John W. Doberstein (Philadelphia: Evangelical Lutheran Ministerium of Pennsylvania and Adjacent States, 1942-58), 3:78.

[11]John Fitzgerald to Sullivan, September 21, 1777, PGW, 11: 278.

[12]“Diary of Lieutenant James McMichael,” 152; Muhlenberg Journals, 3: 78; Knox diary, September 22, 1777.

[13]Washington to John A. Washington, October 18, 1777, PGW, 11: 551.

[14]Knox to his wife, September 24, 1777, in Drake, Life and Correspondences of Henry Knox, 50; Howe to Germain, October 10, 1777, in The Parliamentary Register, 10: 429-30.

[15]Council of War, September 23, 1777, PGW, 11: 295; Washington to John Hancock, September 23, 1777, PGW, 11: 301-302.

[16]General Orders, September 22, 1777, PGW, 11: 288; Washington to George Gibson, September 22, 1777, PGW, 11: 290-91; Henry Knox diary, September 22, 1777.

[17]Thomas J. McGuire, The Philadelphia Campaign, Volume 1: Brandywine and the Fall of Philadelphia (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2006), 321.

[18]Ibid.; Kippling and Smith, At General Howe’s Side, 35; Council of War, September 23, 1777, PGW, 11: 294-96; Knox diary, September 22, 1777.

[19]Howe to Germain, October 10, 1777, Parliamentary Register, 10: 429-30.

One thought on “The Feint That Never Happened: Unheralded Turning Point of the Philadelphia Campaign”

I think you have made a strong case that there was no real feint. What I will say about General Howe’s position at his camp at Charleston Sept 21-22 was that he likely set up the encampment with the intention to cross at the Fatland Ford. He had along Engineer Archibald Robertson, who before the war had surveyed all the Schuylkill River fords from Philadelphia to Reading, this giving him excellent information on the fords. The sending of the trumpeter across the river to tell Washington that he could attend the wounded from Paoli I believe was a ruse intended to see if the water depth at Fatland Ford was low enough to cross after the Sept 16 hurricane. At the British camp at Charlestown (depicted in Andre’s Journal) the Light Infantry, Grenadiers and Guards were placed on the right flank on the Gulph Road heights overlooking the Fatland Ford area. In addition to these strike forces that that outflanked and defeated the Americans at Brandywine, the British placed 4 – 12 pounders that would have commanded and protected a crossing to the north side of the river. The rest of the British encampment stretched westward towards Phoenixville. When Howe made the decision to cross on the 22nd and 23rd of September, the troops simply went east to the ford, the Guards leading the way and the rest of the army marched east following the lead troops across the ford. I think the position of the Crown forces makes a good case that they intended to cross at Fatland.

It would have been a fight had Washington chosen to stay in the vicinity, but it’s a chance Howe would have taken I think with his crack troops in the van and the artillery protecting the move. The Americans had only 3 and 6 pounders and would have been at a distinct disadvantage on the low ground on the north side of the river. For Washington’s part, as he described in a letter to the president of the Continental Congress John Hancock on 23 September, he didn’t have the best information on the British movements and likely feared another outflanking on the right as Howe had done to him on several occasions. I would also say, as Washington points out in the same letter that the troops lacked shoes, other supplies and ammunition (ruined at the Battle of the Clouds) making the supply depot at Reading something he could not lose. A bad decision, in hindsight, maybe, but he could not afford to lose his army. Losing Philadelphia was a blow, but one that the cause could recover from.

Marc Brier

Former Park Ranger Valley Forge National Historical Park