Alexander Hamilton’s life has been documented extensively and his exploits as an adult are well known. His early childhood, however, has long been a subject of debate and, until recently, was largely shrouded in obscurity. Evidence published by historian Michael Newton in 2019 has provided new insights into Alexander Hamilton’s formative years. Despite this new information coming to light, a large gap still exists in our knowledge of the life of one of America’s most brilliant Founding Fathers. Recent research in the Dutch National Archives in The Hague by the authors has uncovered another piece of the puzzle, thereby filling a large gap in Alexander Hamilton’s “missing” years in the early 1760s.

Until recently, Alexander’s own claims and a lack of evidence to the contrary led historians to believe that he was born and raised on the island of Nevis.[1] Newton’s research demonstrated that the story is more complicated and that Alexander did not spend all this time, if any, on Nevis.[2] Alexander’s parents, Rachel Faucett and James Hamilton, met on St. Kitts in the early 1750s. About two years later, Alexander’s older brother James Jr. was born, likely on that same island.[3] Records indicate the family left for St. Eustatius in 1753 “on account of debt.”[4] This has been the last documentation of the Hamiltons’ place of residence until 1765, when the family moved to St. Croix. Various witness accounts and church records place the Hamilton family on St. Eustatius and St. Kitts between 1753 and 1759, but evidence of where they resided during this period has not yet been discovered.[5] Sometime in the mid-1750s, Alexander Hamilton was born. While his date of birth has been a matter of much debate, Newton provides compelling evidence for Alexander’s birth date between February 23 and August 5, 1754.[6] His birthplace, however, is still in question, as lack of records has allowed multiple islands to be considered as possibilities.

Before elaborating on the newly-found evidence relating to the Hamiltons’ whereabouts between 1759 and 1765, it is important to provide a short historical overview of St. Eustatius. This island, as will be demonstrated, is where young Alexander spent a significant part of his childhood. Affectionately called Statia by its current 3,200 inhabitants, St. Eustatius is an eight-square-mile volcanic island located in the northeastern Caribbean, eight miles north of St. Kitts. Statia was first permanently colonized by the Dutch in 1636 and changed hands twenty-two times between the Dutch, French, and British, until Dutch rule was permanently reinstated in 1816. The island initially developed like many other Caribbean colonies. The Dutch settlers established cotton, tobacco, and sugar plantations in an attempt to develop a plantation economy.[7] The island’s relatively dry climate, however, hindered its economic development into a successful plantation colony. The Dutch eventually turned to their commercial instincts and declared the island a free port in 1756. With import duties abolished, an increase in trade activities with ports across the Atlantic World resulted in the construction of a mile-long strip of hundreds of buildings including warehouses, merchant homes, shops, trade offices, brothels, and taverns along Statia’s leeward shore.[8] This bustling trade center, wedged between steep cliffs on one side and the Caribbean Sea on the other, was called the Lower Town. Statia’s population increased from around 2,000 people in the 1740s to 8,476 people in 1790.[9] After 1760, the number of vessels arriving on St. Eustatius ranged between 1,800 and 2,700, but on occasion this was even exceeded; in 1779 a staggering 3,551 ships were recorded.[10] Ships from Europe and North America brought manufactured goods and provisions in exchange for products such as sugar, rum, and cotton from surrounding islands. Enslaved Africans were also frequently traded on the island. Moreover, St. Eustatius played an important role during the American Revolution, during which the North American rebels obtained large quantities of arms, ammunition, and gunpowder from the island. The importance of St. Eustatius in the Revolutionary War is aptly illustrated by a quote from Lord Stormont, who declared in British Parliament that “This rock [St. Eustatius] of only six miles in length and three in breadth has done England more harm than all the arms of her most potent enemies and alone supported the infamous American rebellion.”[11] Statia’s support to the rebels eventually led to the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780-1784) and the sacking of the island by the British in 1781. After another brief period of economic prosperity following the end of the war, French trade restrictions in 1795 caused the collapse of the island’s economy. In the ensuing years, St. Eustatius became an almost forgotten colony.[12]

New Discoveries

In an effort to locate additional documentation pertaining to Alexander Hamilton’s early whereabouts, the archive of the Second Dutch West India Company (Tweede West-Indische Compagnie), held at the National Archives in The Hague, was consulted.[13] This archive holds a trove of historical information from Dutch overseas colonies. Among other things, it contains dozens of thick volumes filled with letters and reports from St. Eustatius to the Heren X, the board of the Second Dutch West India Company. Every year, the Heren X were provided with updates on the state of the island, including lists of incoming and outgoing ships, notes from the governor, the island’s financial reports, and census records. It is the latter category that this article is concerned with, and in which the authors found evidence of the Hamilton family living on St. Eustatius in the 1760s.

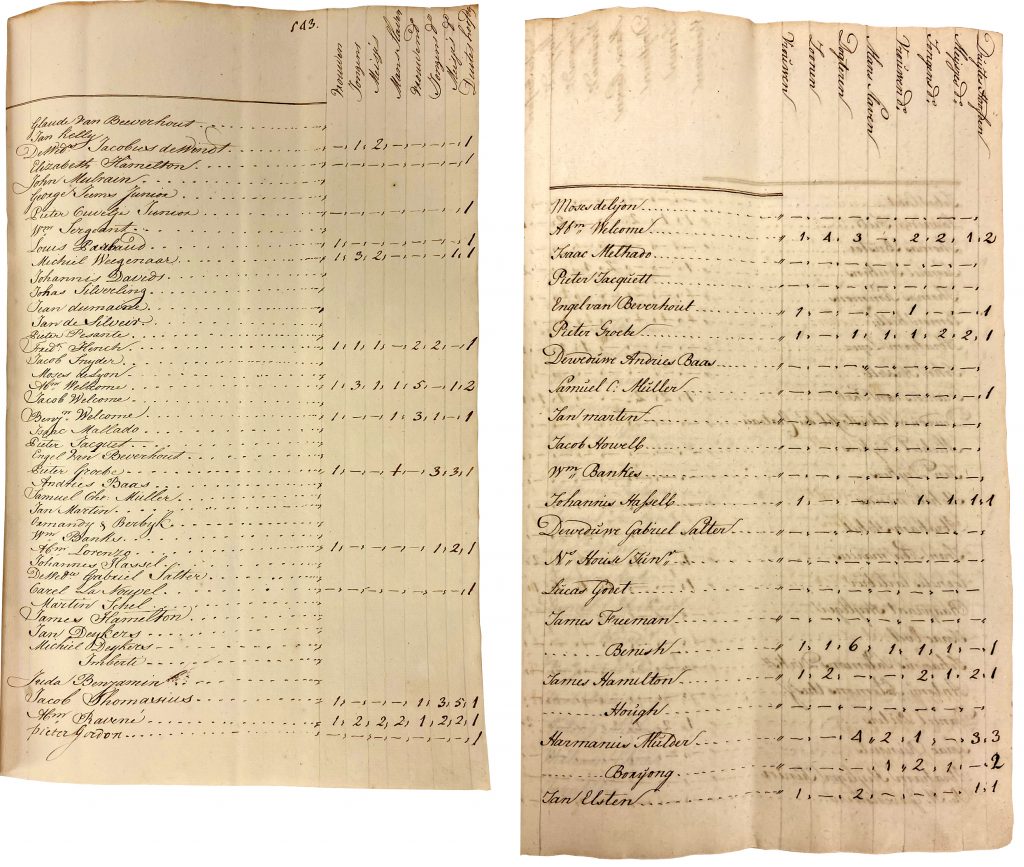

Statia’s census records are organized in a table format; they are divided into free male and free single female inhabitants of the island, with accompanying information on additional members of the household. These include the categories of wives, sons, daughters, enslaved males, enslaved females, enslaved boys, enslaved girls, and the number of taxable people in the household. This last category, named Duytes hoofden, refers to a head tax, known at the time in Dutch as hoofdgelden. This tax was levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual. It is unclear who exactly was subjected to this head tax on St. Eustatius, and under which circumstances. In some census entries, more taxable persons are listed than there were free people in the household, but less than the number of enslaved. This means that enslaved persons were partially subjected to head tax, most likely above a certain number or only a certain demographic.[14]

The St. Eustatius census records list members of the Hamilton family living on St. Eustatius from 1759 to 1767.[15] No Hamiltons are listed in the 1758 census. The 1759, 1760, 1761, and 1762 census records all contain an entry for James Hamelton by himself.[16] He was exempt from head tax in 1759 and 1761, but not in 1760 and 1762. It is unsure where Rachel, James Jr., and Alexander lived from 1759 to 1763. They may have gone to Nevis or another island not associated with the Hamilton family. If James worked as a sailor during this time, as he would later in life, his profession might have given him ample opportunity to visit his family on a nearby island. The census records from 1763, 1764, and 1765 list James Hamilton, this time spelled correctly with an ‘i’. More importantly, James is now not listed alone. The records for these years show his wife and two sons listed as well. Moreover, five enslaved are listed as part of their household: two adult women, one boy, and two girls. During these years, the Hamilton household thus consisted of nine people. Only one person was subjected to head tax, which was most likely James.[17]

In 1765, the Hamiltons moved to St. Croix, 105 miles west of St. Eustatius. Here, James first worked as a sailor aboard the ship Jægeren from approximately February 20 to April 6, 1765. Records indicate that his family followed James in April of that year. While on St. Croix, Rachel was able to turn a profit running a store, providing her sons with a comfortable life.[18] This can be corroborated by the fact that she retained enslaved persons, which she likely brought with her from St. Eustatius. After his sailing contract ended, James became employed as a debt collector.[19] James and his family’s paths diverged sometime in 1766. It is unknown how long James was on St. Croix, but it is believed he left between 1766 and 1768. However, in 1766 and 1767 James is still present in the St. Eustatius census records, filling in two years that were previously unknown. He may not have changed his place of residency from St. Eustatius to St. Croix because he frequently traveled or he was not sure where he would spend most of his time due to his profession. His departure from St. Eustatius in early 1765 may only have been temporary and he might have planned to return before the end of the year. In 1766 and 1767, James is listed by himself and exempt from head tax. After 1767, he disappears from Statia’s census records.

For the Hamilton family, the single head tax in their entry was most likely applicable to James, as he is also listed as taxable when he was on the island by himself in 1760 and 1762. The newly-discovered records indicate that James was exempt from head tax in 1759, 1761, 1766, and 1767. The 1764 census records show that in this year, 358 out of 588 heads of households were exempted from head tax, so this was quite common. This suggests that there were probably several conditions or prerequisites that resulted in an exemption. A few possible explanations for the exemption could be that if James was still traveling between islands, doing various jobs such as sailing and debt collecting, or did not own any taxable property, head tax might not have been extracted from him on St. Eustatius.

As noted by Newton, James Hamilton was a common name in the eighteenth-century Caribbean. There were, for example, several James Hamiltons living on St. Croix at this time.[20] The fact that the James Hamilton in the newly-discovered census records had a family of one wife and two sons is, however, highly coincidental, especially since the Hamiltons in question had spent time on St. Eustatius before and they do not appear in any known records on other islands. Moreover, James Hamilton’s wife and two sons disappear from the St. Eustatius records after 1765, when the documentary record shows they moved to St. Croix. It can therefore be concluded that it is in fact Founding Father Alexander Hamilton’s family that is listed in the newly-found records.

The Hamiltons did quite well for themselves on St. Eustatius. This is reflected in the fact that they accrued sufficient wealth to buy and sustain five enslaved persons during their time there.[21] They could have worked in and around the house or at a possible family venture. Additionally, the family may have rented out their enslaved, as this was a common practice on the island. While the number of enslaved working in a household was by no means the only indicator of one’s economic standing, acquiring enslaved persons was a significant investment and there were several recurring costs associated with enslaving them, such as providing housing, food, and clothing. As such, being an enslaver alludes to, at minimum, a healthy income and a decent financial position. The Hamiltons’ enslaved could have already been living with them on a different island prior to the entire family relocating to St. Eustatius in 1763 or the Hamiltons could have acquired them upon moving there. To place the Hamiltons’ number of enslaved into perspective, one has to look at the entire Statian population at this time. The island’s census records from 1764 reveal 182 out of 588 heads of households to be enslavers. Some people had large numbers of enslaved, such as merchant and future Governor Johannes de Graaff, who enslaved fifty-one, but most only enslaved a few. The average number of persons enslaved by individuals on the island in 1764 was 7.2. From this data, it can be concluded that the Hamiltons were among the 31 percent of families on the island who actually enslaved persons, but enslaving slightly below the average number. This data provides some insight into the Hamiltons’ standing within society and suggests they were comfortably situated within the island’s middle class.

Life on St. Eustatius

There were three areas on the island where the Hamiltons could have lived: the trade district of Lower Town, the residential area of Upper Town, or the countryside. Since housing in Lower Town was very expensive and there are no indications that the Hamiltons at this time were involved in extensive trading activities, it is unlikely they could afford to live in this area with a household of nine people.[22] The island’s countryside was dotted with plantations and small homesteads. Since the Hamiltons enslaved five persons, they may have lived on a homestead in the countryside and put their enslaved to work on a small farm. They did not, however, enslave any adult males, so this seems an unlikely scenario. Most likely, the Hamiltons lived in Upper Town, the island’s main settlement on the cliffs overlooking Lower Town. This is where most middle-class citizens resided. Upper Town was very different from the hustle and bustle of its seaside counterpart, but it was still a busy place where people vended provisions and merchandise in the streets and on the market. Moreover, government buildings, places of worship, and the island’s main fort were all located in Upper Town. Eighteenth-century travelers describe most buildings in Upper Town as single-story wooden constructions topped with a shingled roof. These houses usually had three rooms: one central room that served as a public space and two bedrooms to the sides.[23] Buildings in Upper Town reflected a combination of Dutch, English, and French architectural styles. Outdoor kitchens contained typically French and Dutch ovens. Houses were built close together and included small gardens. It was not uncommon to house one’s enslaved in Upper Town. For example, John Bailen enslaved six laborers who were housed in two dwellings on his urban property in Upper Town.[24] The August 17, 1792 edition of the St. Eustatius Gazette contains an advertisement of a house for sale in Upper Town that contained “negroe houses” as well. The Hamiltons could have housed the two enslaved adults and three children on their urban property as well.

St. Eustatius in the 1760s was an interesting place to live in many respects. The following observations provide some context as to what island life must have been like for the Hamiltons. An account from Scottish Lady Janet Schaw, dating to 1775, shows St. Eustatius to have been a very cosmopolitan place: “Never did I meet with such variety; here was a merchant vending his goods in Dutch, another in French, a third in Spanish . . . They all wear the habit of their country, and the diversity is really amusing.”[25] With thousands of ships arriving from all over the Atlantic World in the previous decade as well, the situation must have been similar in the 1760s. St. Eustatius attracted people from all over the world who wanted to make a quick fortune. As a result, many different religions were practiced on the island. There were Anglican, Lutheran, Dutch Reformed, and Roman Catholic religious groups, each with their own place of worship. The island was also home to a relatively large Jewish community, which had built an impressive synagogue in Upper Town in the 1730s.[26]

Free and enslaved people on St. Eustatius engaged in all vices imaginable. Accounts of drinking excessive amounts of alcohol abound in the documentary record, and smoking played a prominent role in island life as well. The playing of games often accompanied the consumption of alcohol, and it seems that these regularly got out of hand.[27] Merchants, planters and government officials frequently organized elaborate parties where people indulged in eating, drinking, and dancing. Sometimes, free and enslaved people even mingled at parties.[28] There were also several brothels on the island that were frequented by the residents and thousands of sailors calling at Statia each year. It seems daily life for many was characterized by debauchery, but there were more wholesome ways to enjoy oneself. Picnicking was a favorite pastime for visitors and residents, and a hike up the island’s dormant Quill volcano and into its crater was enjoyed by many.[29]

St. Eustatius’ demographic was very different from many other Caribbean colonies whose economies were primarily focused on agriculture. On islands such as Barbados, up to 90 percent of the population consisted of enslaved Africans. Statia’s demographic was much more balanced, with enslaved people making up 54 percent of the total population of 2,489 in 1764. The reasons for this are twofold. First, the island attracted more free people engaged in commercial activities. The steady increase in trade created a demand for service workers, artisans, sailors, and dockworkers. Second, Statia’s focus on trade meant that fewer people were needed in the cane fields that were not very productive to begin with. Extensive archaeological and documentary research has shown that enslaved people on St. Eustatius had more opportunities to improve their social and economic status than those on other Caribbean islands. On St. Eustatius, many enslaved laborers were employed in maritime trades. Among other jobs, they transported people and goods between ships and shore, for which they often charged fees.[30] The fact that there was a sizable group of free blacks and mulattos on the island further shows that its favorable economic climate provided opportunities even for members of the lowest classes in society.[31]

It was in this setting that the Hamilton family lived from 1763 to 1765. Young Alexander must have been exposed to a society characterized by quick money, debauchery, and loose morals where there were often more transient than permanent residents. It was, however, also a society that was relatively tolerant of religious minorities and where peoples’ dreams could come true, even when born into slavery. It was a place where the Hamiltons’ enslaved may have been permitted more time away from work and opportunities than their counterparts on other islands. From 1763 to 1765, the Hamiltons lived in one of the most cosmopolitan places in the Caribbean, where they could buy almost any type of good someone in Amsterdam, London, or Paris had access to as well. While Dutch was used in most government correspondence, English was (and still is) the language most commonly spoken on the island. Given the vibrant nature of the island’s society at this time, it is not hard to imagine that young Alexander’s experiences on St. Eustatius made a lasting impression on him and may have contributed in some way in shaping him into the famous political figure he was to become.

Conclusion

The newly-discovered census records have filled a large gap in our knowledge of the Hamiltons’ whereabouts. It is now clear that James Hamilton was registered on St. Eustatius from 1759 to 1767. It is, however, uncertain if he actually lived there full time during all these years. From 1763 to 1765, Rachel, James Jr., and Alexander were present with James on St. Eustatius. In addition, they enslaved five persons during these years. These new discoveries, combined with Michael Newton’s recent finds, demonstrate that St. Eustatius played a prominent role in the lives of Alexander Hamilton and his family. Many more questions about the Hamiltons’ lives in the Caribbean still remain. What were they doing on St. Eustatius? Where exactly did they live? Which kinds of activities were the five enslaved involved in? More archival research is necessary to shed further light on the formative years of one of America’s most influential founders.

[1]Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (London: Penguin Books, 2005), 7.

[2]Michael Newton, Discovering Hamilton: New Discoveries in the Lives of Alexander Hamilton, His Family, Friends, and Colleagues From Various Archives Around the World (Phoenix: Eleftheria Publishing, 2019).

[7]Ruud Stelten, From Golden Rock to Historic Gem: A Historical Archaeological Analysis of the Maritime Cultural Landscape of St. Eustatius Dutch Caribbean (Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2019), 19.

[8]Jan Hartog, History of St. Eustatius (Aruba: De Wit Stores N.V., 1976), 38.

[9]Stelten, From Golden Rock to Historic Gem, 104. There may have been up to 20,000 people present on the island during its heyday if one considers the many visitors, temporary residents, and sailors that were attracted by Statia’s economic boom.

[10]Richard Grant Gilmore, “St. Eustatius: The Nexus for Colonial Caribbean Capitalism,” in The Archaeology of Interdependence: European Involvement in the Development of a Sovereign United States, ed. Douglas Comer (New York: Springer, 2013), 44.

[11]Franklin Jameson, “St. Eustatius in the American Revolution,” The American Historical Review 8, no. 4 (July 1903): 695.

[12]Stelten, From Golden Rock to Historic Gem, 21.

[13]National Archives, The Hague, 1.05.01.02.

[14]In the Dutch Caribbean, slaves below ten and above sixty years of age were exempt from head tax in 1854. A similar regulation may have been in place in the previous century.

[15]National Archives, The Hague, 1.05.01.02-624, folio 543; 1.05.01.02-624, folio 1025; 1.05.01.02-625, folio 514; 1.05.01.02-625, folio 596; 1.05.01.02-626, folio 53; 1.05.01.02-626, folio 550; 1.05.01.02-627, folio 56; 1.05.01.02-627, folio 101; 1.05.01.02-251, folio 738.

[16]In 1758, Alexander’s parents were present on St. Eustatius. The island’s church records show that James and Rachel Hamelton, also spelled with an ‘e’, stood as godparents for the baptism of a befriended couples’ son.

[17]In 1766 there was a shift in how the census records were organized. Until 1766, the census records were compiled early in the year, but actually referred to the previous year. This is clearly described on the first page of each census list. In 1766, the census records were compiled twice: once on May 25 (referring to 1765) and once on December 4 (referring to 1766). In 1767, they were only compiled once, on December 3. These referred again to the previous year. The following years’ census records are compiled at the end of each year. They most likely refer to the previous year as was customary before, but they can also refer to the year in which they were compiled as nothing to the contrary can be discerned from the documents.

[18]Newton, Discovering Hamilton, 107.

[21]It should be noted that three out of five slaves were children; nevertheless, if these were old enough, they could have been employed in various tasks that were not physically demanding.

[22]Stelten, From Golden Rock to Historic Gem, 107.

[23]National Archives, The Hague, 3.01.26-161: Narigten van St. Eustatius, 1792.

[24]Richard Grant Gilmore, “The Archaeology of New World Slave Societies: A Comparative Analysis with particular reference to St. Eustatius, Netherlands Antilles” (PhD diss., University College London, 2004), 60.

[25]Janet Schaw, Journal of a lady of quality, being the narrative of a journey from Scotland to the West Indies, North Carolina, and Portugal, in the years 1774 to 1776 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1921), 137.

[26]Stelten, From Golden Rock to Historic Gem, 120.

[30]Jacob Schiltkamp and Jacobus Smidt, West Indisch Plakaatboek. Publicaties en andere wetten betrekking hebbende op St. Maarten, St. Eustatius en Saba, 1648/1681-1816 (Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1979), 408.

6 Comments

Excellent research. We need more like this. Applaud your effort.

Thank you!

On the first census, Who is the Elizabeth Hamelton ? She is second person listed. Same spelling as James.

Hi Ellen,

She appears in all the censuses from that period. I’m not sure who she is; she could be related but there were many Hamiltons/Hameltons in the area at that time. Certainly something to look into more closely.

I’m surprised that the authors give no mention to the excellent work “Alexander Hamilton: The West Indian “Founding Father”, by William F. Cissel (Historian, Christiansted National Historic Site, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior). He gives a great deal of background for the whole period, starting in 1746.

Thank you for posting this. I have done considerable research into this time in Hamilton’s life and have even written a book about it and yet there is information here I’ve never read before, so well done. In Alexander Hamilton: Youth to Maturity, 1755-1788 by Broadus Mitchell, it was written that Rachael Faucette Lavien inherited 3 adult female slaves from her mother Mary Uppington Faucette, named Flora, Esther and Rebecca and she was hiring them out for money to a man named Archibald Hamm, which the Hamiltons most likely continued. They had 3 children, 2 boys named Christian and Ajax and a girl named Rachael. The census may have erroneously listed them as 2 girls and 1 boy.