During the American War of Independence, the British Army officer corps routinely relegated its surgeons and physicians to a secondary status among its ranks. A few regimental surgeons made contributions to medical science, but the vast majority were relatively unknown both in their time and today.[1] American military doctors fared a bit better, but are mostly remembered for their interpersonal squabbles. Dr. Hammond Beaumont, surgeon to the British Army 26th Regiment of Foot, broke the mold and became remarkably well known and respected during the American Revolution. His prominence, however, emanated from extracurricular activities outside of normal military duties.

A career officer, Dr. Hammond joined the 26th Regiment as its surgeon in 1761 and during the summer of 1767 embarked from Ireland for garrison duty in colonial North America. Gen. Thomas Gage first deployed the regiment to three towns in the New Jersey. Dr. Hammond found New Jersey to be agreeable and on December 7, 1768 he married Elizabeth Trotter at the St. John’s Church in Essex (now Union) County.[2] Two years later, British commanders repositioned the 26th Regiment to New York City. Soon after, Dr. Beaumont first ventured beyond his regimental duties into a profit-making private medical practice. Venereal disease ran rampant among both soldiers and the general population. Suffering from the afflictions associated with syphilis, Thomas Flackfield, a private in the 26th Regiment, sought medical care from the regimental surgeon as treatments from local physicians failed to alleviate his distress.

Dr. Beaumont prescribed a multi-stage regimen featuring Keyser’s Pills. Developed and marketed by Jean Keyser, a French military surgeon, the widely distributed pills consisted of a mixture of mercuric oxide and acetic acid. The private suffered from one hundred and twenty-nine ulcers covering all parts of his body. After a taking eleven hundred and seven Keyser’s Pills over a four-month period, the private’s symptoms disappeared. With this “miraculous recovery,” Dr. Beaumont sensed a profit-making opportunity and entered into a cooperative relationship with a famous newspaper editor and drug distributor. Publisher of the New York Gazetteer or the Connecticut, New Jersey, Hudson’s River, and Quebec Weekly Advertiser, James Rivington imported Keyser’s Pills from Dr. James Cowper in London and advertised the pills and the services of Dr. Beaumont to afflicted readers and other members of the community. In newspaper advertisements throughout the colonies, Rivington assured the authenticity of his pills and attested to Dr. Beaumont’s curative services.[3] In addition to syphilis, the Dr. Keyser’s Pills were advertised to combat a host of afflictions including rheumatism, asthma, and sciatica, all common afflictions of eighteenth century soldiers. The pills were even thought to cure “giddiness of the head.”[4] Demonstrating their popularity, American general Henry Knox also sold Dr. Keyser’s Pills provided by Rivington in his Boston book store.[5]

Anticipating additional profitable ways to augment his regimental income, Dr. Beaumont engaged in a business venture with Dr. James Latham (c. 1734-1799) surgeon to the 8th Regiment of Foot. Latham held a lucrative franchise for the northern colonies to administer a smallpox inoculation using the propriety Suttonian method. In the 1760’s, Dr. James Sutton and his son David developed the Suttonian system of inoculation. The process started with abstaining from meat and alcohol for two weeks prior to the inoculation. In week three, a charged lancet was held slantwise to create a one sixteenth of an inch-deep incision in the skin to insert some of the disease. Afterwards, regular purges, exercise in the open air, a bland diet and cold-water baths were ordered. With a bit of mystery, the attending physician administered a secret remedy to cap off the treatment regimen. No one is sure of its exact ingredients, but later physicians believe Sutton’s confidential remedy consisted of mercury and antimony, two common medical components of the period. The undisclosed remedy added a perceived competitive advantage and a barrier to entry to a procedure viewed both as dangerous and controversial by the general public. By stressing the secret remedy and the extensive regimen, Dr. Sutton sought to disadvantage physicians who had not purchased a franchise.

During an earlier posting in Canada, Dr. Latham first practiced the Suttonian method. Given its notable and immediate success, Latham “sub-franchised” the system to other physicians throughout New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. When Dr. Beaumont learned that the 26th Regiment was to be transferred to Montreal, he purchased the right to administer the inoculation in Canada from Dr. Latham. It was a profitable business. In addition to the pills, the standard treatment charge for a British soldier was one guinea and likely more for a civilian. Doctors practicing the Suttonian method developed a reputation for highly successful inoculations with few deaths and mild cases, attracting many patients. For Dr. Latham, the practice became so lucrative that he quit the British Army to attend to his growing network of franchised physicians and his burgeoning private practice.

As the Revolutionary War intervened, Dr. Beaumont would not experience the same level of financial success as Dr. Latham. Beaumont’s outmanned 26th Regiment attempted to stem the determined 1775 American invasion of Canada. The Americans overwhelmed the widely dispersed components of the 26th Regiment at Fort Ticonderoga, Fort St. Johns, Montreal, and the St. Lawrence Valley. The American Rebels captured Beaumont at the latter location on November 18 and sent him to a prisoner of war camp in Reading, Pennsylvania.[6] During his captivity, he continued to inoculate prisoners. After a year of captivity, Beaumont and the 26th Regiment returned to New York City under terms of a negotiated prisoner exchange.

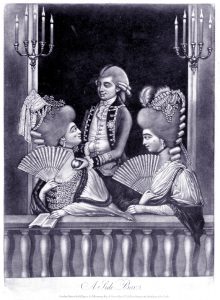

In occupied New York City, Dr. Beaumont’s life and career took a “dramatic” turn. British commanders reassigned him to the garrison’s hospital as one of the eight attending physicians and surgeons.[7] Beaumont, however, turned most of his attention to the stage, becoming a thespian. Theater enthusiastic British officers organized an acting troupe to entertain the officer corps and to generate funds to be donated to stranded widows and children of British soldiers. The officer troupe appropriated the red-painted John Street Theater and renamed it the Royal Theater. More senior British officers played the male parts with the junior or younger officers playing female roles. Mistresses and professional actresses sometimes became cast members. Joining the 1777 season, Dr. Beaumont performed as the principle “low comedian” engendering raucous laughter from satire, bawdy language, double entendras, and crude jokes. He became a hit during the well-attended, five-month theater season of weekly plays. In a bow to the actors’ professional responsibilities, several of the performances were cancelled as result of military operations.

When Gen. Sir William Howe launched his campaign to capture Philadelphia in the fall of 1777, Dr. Beaumont accompanied the invasion force and re-focused on his duties as a regimental surgeon. In January 1778, he participated in a curious mission into Rebel territory. To provide clothing, supplies, and medical aid to captured British soldiers, he received a pass from Gen. George Washington to cross Rebel lines and attend prisoners in Reading, Pennsylvania. The planned humanitarian mission got caught up in the politics between Washington and the Board of War led by Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates. Although the British supply force received a pass for safe transit from Washington, the Board of War ordered their detention. During the detention dispute, Rebel officers discovered counterfeit Continental currency in the British supply wagons. This breach of protocol and gentlemanly honor infuriated the Rebels and tainted the entire British mission. Even though Washington eventually straightened out the conflicting orders and allowed the British mission to proceed, Dr. Beaumont and the supply force abandoned their efforts to reach Reading and returned to Philadelphia.

Rebuffed in his efforts to care for sick and wounded prisoners, Dr. Hammond quickly returned his attention to the stage. Transformed from a place to care for the sick and wounded, the red brick and wood Southwark Theatre on Philadelphia’s South Street reopened as a playhouse for the amateur thespian British officers. Oil lamps lit the stage and Capt. John André and Capt. Oliver Delancey painted the background scenery.[8] In a season stretching from January 19 to May 19, the cast performed thirteen different plays. The British officer troupe charged admission prices of one dollar for the box or the pit and fifty cents for the gallery. In general, the performances were well attended and well received. Demand for seats was so high that newspaper notices had to be placed to warn patrons without tickets not to bribe the door keepers.[9]

Critics regarded Dr. Beaumont as the star of the troupe. Audiences especially hailed Beaumont’s performance in the comedy farce The Mock Doctor, or the dumb lady cured, a Henry Fielding adaption of Moliere’s Le Médecin malgré lui.[10] Beaumont played the lead role, Gregory, the husband impersonating a doctor at the request of his wife. British Capt. John Peebles remarked in his diary that “Dr. Beaumont shin’d in the mock Doctor.”[11] Given the critical acclaim, the troupe restaged the play several times over the subsequent months. A fan of the theater, General Howe regularly sat in the “Royal Box” with his mistress. In a peculiar turn of events, Rebel Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, who at the time was a British prisoner, accompanied General Howe to a March performance.[12]

At the end of the theater season, British officers staged an opulent outdoor pageant known as “The Meschianza” in honor of the departing General Howe. Beaumont played a prominent role in this over-the-top extravaganza. He acted the part of a herald in the center of a square of knights and their lady escorts. After a flourish of trumpets, Dr. Beaumont, in his best theatrical voice, exclaimed, “Knights of the Blended Rose by me the Herald, proclaim and assert that the Ladies of the Blended Rose excel in wit, beauty, and every accomplishment, those of the whole world; and should any Knight or Knights be so hardy as to dispute or deny it, they are ready to enter the lists with them and maintain their assertions by deeds of arms, according to the laws of ancient chivalry.”[13]

Dr. Beaumont evacuated Philadelphia with the British Army, now under the command of Gen. Henry Clinton, and returned to New York City. Once back in New York, Beaumont resumed medical duties at the garrison’s hospital. Over the next two years, his interest and devotion to the theater intensified. In addition to acting, he became the playhouse treasurer and then in 1779 he assumed the role of co-manager of the theater. Soon after, a personal tragedy struck Beaumont. In the spring of 1780, Elizabeth (Trotter) Beaumont passed away in her thirty-seventh year after twelve years of marriage.[14]

Despite his personal loss, Dr. Beaumont remained highly engaged in public entertainment events. The next year he organized evening walks at Fort George for gentlemen and their ladies. Offered by subscription of one guinea, a band serenaded the strolling couples.[15] Also during this period Beaumont devoted his time to dealing with the increasing complexity of the growing and prosperous theater business generating almost four thousand pounds per season. The highly active theatre remained in production through 1782. Nearing the end of its annual run, Beaumont solicited nominations from regimental commanding officers of deserving widows and children to receive surplus funds generated by theater performances. Under his management, a record of over eight hundred pounds was raised in the 1781-2 season to support the families of deceased British soldiers, the highest amount in any of the seven years of theater operation. After this successful season, tragedy again struck. Dr. Hammond Beaumont died on October 1, 1782. An obituary in the Royal Gazette remembered Beaumont as, “a Gentleman of infinite pleasantry and humour, very respectable in his profession, and greatly esteemed by a numerous acquaintance.”[16] After his death, the theater floundered.[17]

Initially, like many other physicians and officers, Dr. Beaumont sought to leverage his situation in North America for personal financial gain. He energetically pursued a lucrative private medical practice while holding an active army surgeon’s commission. But he found his true passion in the theater. Acting and theater management engendered respect and acclaim from his fellow officers that Beaumont’s normal regimental duties did not provide. While there is no evidence that the theater interfered with the doctor’s military duties, the demands of weekly theater productions consumed a predominance of his time. As a result, Dr. Beaumont was not known for being an outstanding army surgeon but he was well liked and esteemed for his captivating thespian roles. While many people find satisfaction from their advocations and careers, to follow your true passion is a good life lesson for all!

[1]From a professional medical perspective, Tabitha Marshall argues that British Surgeons Thomas Dickson Reide, Robert Jackson and Robert Hamilton stand out for making significant contributions to medical science during the Revolutionary Era.

[2]New Jersey Historical Society, Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey(Press printing and publishing Company, 1900), 408, books.google.com/books?id=qEBKAQAAMAAJ. The couple’s marriage license is dated November 17, 1768.

[3]James Rivington to Messieurs Bradford,Pennsylvania Journal or Weekly Advertiser, November 10, 1773.

[4]New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, June, 22, 1772, Supplement, 2.

[5]John L. Smith, “Henry Knox, Drug Dealer?,” Journal of the American Revolution, February 25, 2014, allthingsliberty.com/2014/02/henry-knox-drug-dealer/.

[6]Philadelphia Gazette, December 27, 1775.

[7]“Promotions, War Office July 22, 1777,” Pennsylvania Ledger, or the Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey Weekly Advertiser, October 22, 1777.

[8]Darlene Emmert Fisher, “Social Life in Philadelphia During the American Revolution,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies37, no. 3 (July 1970): 249.

[9]Philadelphia Ledger, January 26, 1778.

[10]Philadelphia During the Revolution, 371.

[11]John Peebles, John Peebles’ American War: The Diary of a Scottish Grenadier, 1776-1782, ed. Ira D. Gruber(Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998), 172.

[12]Jared A. Brown, “‘Howe’s Strolling Company’: British Military Theatre in New York and Philadelphia, 1777 and 1778,” Theatre Survey18, no. 1 (1977): 39, doi.org/10.1017/S0040557400005184.

[13]David Hamilton Murdoch, ed., Rebellion in America: A Contemporary British Viewpoint, 1765-1783(Santa Barbara, CA: Clio Books, 1979), 623.

[14]New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, May 29, 1780.

[15]Royal Gazette, Wednesday, July 25, 1781.

[16]New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, October 7, 1782.

[17]After the war, the Royal Theater would regain its original name and become a major force in the rebirth of the American stage.

Recent Articles

That Audacious Paper: Jonathan Lind and Thomas Hutchinson Answer the Declaration of Independence

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Recent Comments

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Thank you Eric! I should say that I have enjoyed your work...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...