The role of Connecticut’s Sons of Liberty is one that exemplifies the state’s rich history of self-governance and fiercely independent spirit. Their swift reaction to the passage of the Stamp Act of 1765 shattered the political landscape of Connecticut, known ironically as “the land of steady habits.” Later, a few select Sons and their respective affiliates would transition into roles on Committees of Correspondence throughout the colony. It has been often misconstrued that the Sons of Liberty were a singular angry mob that patented the art of tarring and feathering British tax collectors, but that was nowhere to be seen in Connecticut. The story of Connecticut’s Sons of Liberty is a decade-long modern grassroots movement; a community-oriented example of how it was possible to permanently undermine Britain’s administration of the Thirteen Colonies through careful, non-violent resistance.

To the Sons, the Stamp Act was an offensive violation to the large degree of political sovereignty granted by Connecticut’s colonial charter and outrage was quick to engulf major centers of industry including New Haven, New London, and Norwich. Eastern Connecticut in particular became a revolutionary hotbed for resistance to the Stamp Act and produced many Sons of Liberty including Col. John Durkee and Brig. Gen. Jedediah Huntington both from Norwich, as well as Declaration of Independence signer William Williams of Lebanon, Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam of Pomfret, Capt. Hugh Ledlie of Windham, and the infamous Benedict Arnold, born and raised in Norwich and resident of New Haven between 1762 and 1775. Other notable members of the Connecticut Sons included Jonathan Sturges of Fairfield, Rev. Stephen Johnson of Lyme, John McCurdy of Lyme, Eliphalet Dyer of Windham, and Jonathan Trumbull of Lebanon.[1]

Born in Windham, Connecticut in 1728, John Durkee settled in the Bean Hill section of Norwich upon reaching adulthood; his heroics in battle, business, land-speculating, and leadership in the Sons of Liberty earned him status as a local legend as well as a memorable nickname: the “bold bean hiller.” He had neither the privilege of wealth, nor formal education yet historian Frances Caulkins notes, “Could the life of this able and valiant soldier be written in detail, it would form a work of uncommon interest.”[2] Many details of Durkee’s early life remain obscure, yet being the son of renowned Deacon William Durkee, his upbringing in a devout Christian household had a big impact on his formative years. In 1756, Durkee enlisted in the militia and served in the French and Indian War earning the rank of major by the war’s end in 1763. He commanded the Third Company, a Norwich unit, and served in multiple theaters of the war including Gen. Jeffrey Amherst’s capture of Montreal, and the Siege of Havana in 1762.[3] After the war’s conclusion, he returned to Norwich where he maintained a farm and kept an inn and tavern within his home. His experience in military leadership and personal charisma made him a perfect fit for leading the local Sons of Liberty against the Stamp Act.

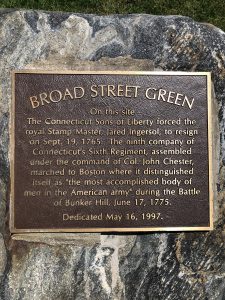

Though the Stamp Act passed in March of 1765, the implementation would not occur until November, yet the Connecticut Sons wasted no time in outlining their three specific objectives: prevent the distribution of stamps in Connecticut, galvanize public opposition to the Stamp Act, and remove as many of their political opponent’s from power as possible. To carry out their mission, the Sons identified their targets, namely Governor Thomas Fitch and Connecticut’s chief Stamp Agent, Jared Ingersoll.

Tensions rose steadily over the summer of 1765, and little did Ingersoll know that his job would be over before it even began. On June 1, Nathaniel Wales, Jr. of Windham wrote to Ingersoll heartily offering his services as a deputy stamp agent.[4] Wales was eager and may have had every good intention, but his naiveté caused him to inadvertently paint a target on his back. Several weeks later in a noticeably abrupt change of heart, Wales wrote to Ingersoll again on August 19 announcing that he was no longer up to the task, stating, “I am of opinion that the Stamp Duty can by no means be Justifyed & that it is an imposition quite unconstitutional and so Infringes on Rather destroys our Libertys and previlidges that I Cant undertake to promote or encourage.”[5] What Wales didn’t mention at the time is how Windham’s Sons of Liberty succeeded in making him reconsider this prospect through methods known only to him; years later, Wales joined Windham’s Committee of Correspondence.

Just two days after Wales’s resignation, Jared Ingersoll was burned in effigy on the town green in Norwich, and again in New London, Windham, Lebanon, and Lyme, an ominous foreshadowing of what his future might soon become. Additional letters to Ingersoll warned him that the targeting of Stamp Agents was proving exceedingly effective as described by Boston agent Andrew Oliver, who wrote to Ingersoll on August 26:

Sir The News Papers will sufficiently inform you of the Abuse I have met with. I am therefore only to acquaint you in short, that after having stood the attack for 36 hours—a single man against a whole People, the Government not being able to afford me any help during that whole time, I was persuaded to yield, in order to prevent what was coming[6]

As calls for his resignation amplified in New Haven, Ingersoll dismissed the Sons and would bring his case before Governor Fitch in September. Unbeknownst to him at the time, the Sons of Liberty were already a step ahead of him. On September 18, 1765, John Durkee and Hugh Ledlie marched from Norwich to Hartford with a large band fellow Patriots, to intercept Ingersoll who was also presently riding to Hartford from New Haven by himself. The next day, Ingersoll was met in Wethersfield by the armed contingent dubbed, Durkee’s “Irregulars,” reported to have been anywhere from 500 to 1,000 men strong from all over eastern Connecticut.

Seated upon his valiant white steed, John Durkee and his men respectfully yet firmly confined Ingersoll in a nearby home, making it abundantly known that he would advance no further unless his resignation as Stamp Agent was formalized. The details of the entire incident were documented by Ingersoll himself in an article he published in the Connecticut Gazette on September 27, 1765. In spite of the fact that Ingersoll was incredibly outnumbered by the intimidating crowd, Durkee and his militia treated him with courtesy and respect worthy of a gentleman such as him. For a moment Ingersoll believed that with a little quick wit he could persuade his captors to show mercy and let him on his way, but after three hours of back-and-forth deliberation, he realized his odds were not improving. He conceded to Durkee and was subsequently escorted to Hartford in which he read his letter of resignation before the General Assembly. In a grand fashion, the Patriot crowd made a spectacle of their victory by compelling the now former stamp agent to raise his hat and shout “Liberty and Property!” three times; Ingersoll stated to the “Commandant” of the group, likely Durkee himself, “I did not think the cause worth dying for, and that I would do whatever they should desire me to do.”[7] Israel Putnam called on Governor Fitch to advise him of the outcome even demanding the Governor hand over any access to stamps should they arrive from England. In their famous exchange, Fitch asked Putnam, “But if I should refuse your admission?” to which Putnam boldly replied, “In that case, your house will be leveled to the ground in five minutes!”[8] Though his duties to the Crown were finished, Ingersoll didn’t fully escape the eyes of the Sons. While back home in New Haven, Ingersoll had the pleasure of reporting fairly regularly to Putnam and Ledlie while they took the liberty of combing through Ingersoll’s personal correspondence, as well as the correspondence of his associates, for the better part of six months; evidently they suspected that he might still be up to no good.[9]

Not long after this major victory for the Sons, Connecticut sent Eliphalet Dyer, William Samuel Johnson and David Rowland as delegates to the Stamp Act Congress in New York on October 7, 1765. Ledlie accompanied the delegation and wrote to Samuel Gray in Windham on October 9:

the Great councel . . . now setts Here to [determine] [the] fate of the Brittish Coloneys in North America . . . Nobody Here Knows what is to be [done] after that [fatal] Day Which is Dreded by Every [so called] thinking man . . . in Hopes the present Congress Will Do something Worthey such a Sett of Smart Men as they [appear] to me to be.[10]

The resolutions adopted by the Congress did little to persuade Governor Fitch who remained unyielding in his loyalty to the Mother Country; a conviction on which he would stake his political future. By the start of the new year, the Connecticut Sons of Liberty achieved two out of their three objectives. Not a single stamp was issued in the colony, colony-wide opposition to the act was widespread, and nearly all of their political opponents were out of the picture; Governor Fitch and his deputies were next.

In March 1766, the Sons of Liberty convened in Hartford, akin to a modern-day political party, to nominate a slate of candidates headed by William Pitkin and Jonathan Trumbull to run against Fitch, who previously held the governorship for over a decade. Representation by the Sons of Liberty was strong but noticeably absent was William Williams and his delegation from Lebanon; Williams expressed his disappointment claiming it was due to a miscommunication in timing. The results were a landslide victory for the Sons; Pitkin was elected governor and Trumbull as his lieutenant governor; Colonel Putnam was elected to the General Assembly that year as well. In the end, both Ingersoll and Fitch grossly underestimated the changing political climate in Connecticut yet their sufferings could be described as remarkably tame compared to their counterparts in Boston. Upon repeal of the Stamp Act, Norwich residents erected a liberty pole on the town green with great patriotic fanfare.[11]

Tactics of the Sons of Liberty changed in the latter part of the 1760s with the passage of new acts such as the Townshend Duties, prompting the Sons and their allies to engage in non-importation movements as well as well as promote the production of locally sourced goods, homespun fabrics, and more. Others took a more clandestine approach to subverting British regulations through covert smuggling operations. One of those noted smugglers was the future traitor, Benedict Arnold.

Born in Norwich in 1741, Arnold was noteworthy he was infamous even before his betrayal as his early years were both tumultuous and tragic. Forced out of private schooling in Canterbury, Arnold completed an apprenticeship by age twenty-one with his mother’s cousins, Drs. Daniel and Joshua Lathrop, and in 1762 he set out for New Haven with his sister Hannah. Upon the death of his mother in 1759, his father continued to struggle with alcohol abuse and died in 1761 having squandered the family’s fortune. In addition to Hannah, Arnold had four other siblings who all succumbed to yellow fever at very early ages. His father’s alcoholism was a mark of shame on the family and they suffered publically because of it. Once he left Norwich, Arnold was determined to remake his destiny and never returned to his home town. Though Arnold did excel as a businessman, his utter lack of bookkeeping skills plagued him consistently and he was largely burdened by debts throughout his entire life. Strapped for cash, Arnold sold his family home in Norwich in 1764 home to none other than fellow Son of Liberty Hugh Ledlie, for a sum of 700 pounds sterling.[12]

Arnold established a successful business in New Haven within walking distance of Yale College where he sold books, medicines, and an array of cosmopolitan goods “sibi totique,” from the Latin meaning “for himself and for all.” He personally commanded many of his merchant vessels and his smuggling efforts resulted in major hauls of contraband liquor, but his brash overconfidence failed to keep his operation a secret. As a result, one of his disgruntled sailors threatened to expose Arnold to the authorities. Arnold never took kindly to threats and had the poor sailor flogged not once, but twice, the second time being a public demonstration, and faced a fine of fifty shillings as a result.[13] Though Arnold did have many character strengths, a knack for diplomacy was not one of them.

Arnold was normally never subtle with his feelings or intentions, and on many occasions provided a clear glimpse into the profile of a man whose passion burned fervently for the American cause, standing in stark contrast to his treasonous legacy we’re all familiar with. When news of the Boston Massacre reached Arnold during one of his trips to the West Indies, he wrote:

I was very much shocked the other day on hearing the accounts of the most wanton, cruel, and in-human murders committed in Boston by the soldiers. Good God! are the Americans all asleep, and tamely yielding up their liberties, or are they all turned philosophers, that they do not take immediate vengeance on such miscreants?[14]

When word reached New Haven that hostilities broke out on the Lexington Green in 1775, Arnold immediately marched the second company of the Governor’s Foot Guards, of which he was captain, to Cambridge.

The year 1774 became the year that everything changed. Boston was now under martial law, and the punitive Coercive Acts aimed to punish the town for the destruction of the tea in 1773. Starvation quickly took root only to be compounded by a massive smallpox epidemic the following year. Desperate for aid, an appeal was circulated from Boston’s Committee of Correspondence and on June 6, 1774 at a town meeting in Norwich, the Norwich Committee of Correspondence was formed consisting of Christopher Leffingwell, Jedediah Huntington, William Hubbard, Dr. Theophilus Rogers, and Capt. Joseph Trumbull; Leffingwell would head the committee.[15] A neighbor of the Arnold family, Jedediah Huntington was a noted member of the Sons of Liberty and served valiantly in the American Revolution alongside General Washington and fellow neighbors including John Durkee. Huntington became a successful merchant and served through the entire American Revolution, earning the distinctive recognition of General Washington who regarded him as one of his most trusted commanders. Washington wrote to him on October 16, 1783 stating, “Permit me, My dear Sir to take this opportunity of expressing to you my obligations for the support and assistance I have in the course of the war received from your abilities & attachment to me . . . you have always possessed my esteem & affection.”[16]

In addition to Norwich, additional Committees of Correspondence were established all throughout Connecticut which embarked on a single common mission: provide relief and aid to the citizens of Boston in the form of provisions, food, money, livestock, and intelligence. The first Norwich committee meeting was held on, of all days, July 4, 1774; minutes from the meeting list the names of twenty-six individuals the committee recruited as subscribers to aid Boston.[17] Surviving records from the Norwich committee provide clear details on these proceedings and even reveals the location of where the first meeting took place, the home of prominent resident and local tavern keeper, Azariah Lathrop.[18]

The first installments of aid were in place, just in time for the Sons of Liberty to flex their muscles once again on another unsuspecting victim, similar to what happened to Jared Ingersoll. On the morning of July 6, 1774, Boston loyalist and debt collector Francis Green arrived in Norwich outside Lathrop’s tavern, having been previously chased out of Windham while attempting to collect certain debts on behalf of Boston’s British occupiers. As Norwich sits at the halfway point on land routes between New York and Boston, the intersection of roads outside Lathrop’s tavern on the Norwichtown Green was a major stagecoach stop for many years. Word spread quickly, and the Sons of Liberty were ready for Mr. Green’s arrival. One could only imagine what went through Green’s mind as he witnessed the massive assembly of citizens on the Town Green complete with bells ringing, drums beating, and muskets firing. Unsurprisingly, accounts of the incident from both sides differ immensely. In an affidavit submitted to Massachusetts Gov. Thomas Gage dated July 20, Green named several individuals who affronted his visit, one of them being Simeon Huntington of Norwich who reportedly threw his hands on Green.[19] Green took out the equivalent of a wanted-ad in the Massachusetts Gazette offering a one-hundred dollar reward for the capture of the aggressors, but none were turned in. In fact, Jedediah Huntington was so impressed with Simeon’s bravado, that he wrote to Governor Trumbull on September 9, 1775 expressing his intent to appoint Simeon as a lieutenant within his regiment stating, “I want officers of a military spirit.”[20]

Not long after Francis Green was chased out of Connecticut, the Norwich committee succeeded in assembling the first round of aid, a total of 291 sheep gathered at the tavern of Benjamin Burnham in nearby Newent (Lisbon), Connecticut, in a record dated August 20, 1774.[21] Earlier in July, Samuel Adams had received the Norwich committee’s promissory letters and wrote a personal response fully expressing his sincerest appreciation dated July 11, 1774:

Gentlemen: Your obliging Letter directed to the Committee of Correspondence for the Town of Boston, came just now to my hand; and as the Gentlemen who brought it is in haste to return, I take the liberty to writing you my own Sentiments in Answer, not doubting but they are but they are concurrent with those of my Brethren. I can venture to assure you that the valuable Donation of the worthy Town of Norwich will be received by this Community with the Warmest Gratitude & [disposed] of according to the true Intent of the Generous Donors. . . . The Part which the Town of Norwich takes in this Struggle for American Liberty is truly noble [emphasis added] [22]

A response to Samuel Adams’s letter was written by Christopher Leffingwell to William Phillips in Boston dated August 1774 stating that future donations will be collected and forwarded to further relieve Boston.[23] For over the course of nine months, the donations continued to pour in as Leffingwell promised, not just from Norwich but from all over Connecticut. In April of 1775, Jedediah Huntington wrote on behalf of the committee to Boston stating that additional sheep were being dispatched to the city in addition to a monetary donation of twenty-two pounds and nineteen shillings delivered by Joseph Carpenter, Norwich’s master silversmith.[24] The money was received by David Jeffries on April 19, 1775 and by then, the war was officially underway. The combined efforts of the Connecticut Committees of Correspondence greatly impacted the afflicted in Boston and never went unnoticed or unacknowledged.

The Connecticut committees continued to communicate with Boston and amongst themselves and after the outbreak of war conversations between the committees shifted to matters of intelligence on enemy movements. One such instance is documented on April 28, 1775 where the New London Committee of Correspondence wrote to Norwich stating, “This moment we Received a letter from [New York] letting us know that a Packitt had that moment just arrived with Dispatch’s for General Gage . . . its best to keep a good look out for it.”[25] As the British entrenched themselves in Boston, a series of raids were conducted on Block Island, Fisher’s Island, and Long Island to resupply the regulars with badly needed food and provisions. Christopher Leffingwell wrote to General Washington on August 7, 1775 informing him that the British had seized upwards of 2,000 sheep and cattle from the islands and were transported by ship back to Boston.[26] For Washington and his new army, there was nothing that could have been done to prevent the raids. Though these channels of communication and coordinated efforts were largely disorganized and wholly incomparable to the British, they nevertheless represented a budding foundation for future intelligence operations in the region.

In a way, Connecticut’s Sons of Liberty were ahead of their time, focused on the clear objective of transforming the colony’s future under British rule. They looked after themselves, their families, their neighbors, and brethren in neighboring colonies in a manner which proved that civil disobedience could effect change, even under the threat of death. In one of his many firebrand sermons against the Stamp Act, Rev. Stephen Johnson stated boldly, “O my Country. My dear distressed country! For you I have wrote; for you I daily mourn, and to save your invaluable Rights and Freedom, I would willingly die.”[27] In a letter written in April of 1766, the Norwich Sons stated almost prophetically that they were willing “to Risk even our Lives and fortunes in Defending . . . our Just writes and Liberties against a Wicked and trechirus Ministry.”[28] These words represent a nearly divine vision that would be realized a decade later in the Declaration of Independence, the resolved affirmation that the future of Americans, and of greater mankind, would not live as subjects of a King, but rather as free people governed by the principles of freedom.

[1]Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765-1776 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991), 306-307.

[2]Frances Caulkins, History of Norwich Connecticut from its Possession by the Indians to the Year 1866 (Gaithersburg: New London Country Historical Society, 2009), 421.

[3]Amos Browning, “A Forgotten Son of Liberty” in Records and Papers of the New London County Historical Society: Volume 3 (New London, CT: New London County Historical Society, 1906), 258.

[4]Nathaniel Wales to Jared Ingersoll, June 1, 1765, Jared Ingersoll Papers, ed. Franklin B. Dexter (New Haven, 1918), 325.

[5]Nathaniel Wales to Jared Ingersoll, August 19, 1765, ibid., 325-326.

[6]Andrew Oliver to Jared Ingersoll, August 26, 1765, ibid., 328.

[7]Jared Ingersoll, “Communication to The Connecticut Gazette,” The Connecticut Gazette, September 27, 1765, ibid., 346.

[8]Frederick Albion Ober, “Old Put” the Patriot (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1904), 122.

[9]Joseph Chew to Jared Ingersoll, February 5, 1766, Jared Ingersoll Papers, 377-378.

[10]Hugh Ledlie to Samuel Gray, October 9, 1765, CWF Rockefeller Library Special Collections.

[11]In 1769, John Durkee left Norwich and became a manager of the Susquehanna Company before returning to Connecticut to command the 20th Continental Regiment in 1776 and the 4th Connecticut Regiment in 1777. His career in the Continental Army ended shortly after the Battle of Monmouth where a musket ball shattered his right hand. He passed away in Norwich on May 29, 1782.

[12]Ledlie’s wife Chloe Stoughton Ledlie resided in the former Arnold house until her death in 1769 and gave birth to two children during this time, one of which likely died in infancy. Her five years spent in Norwich were fraught were turmoil and resulted in her being physically confined as described by Frances Caulkins. These circumstances, and others, have resulted in a number of whimsical ghost stories about the allegedly cursed Arnold homestead; the fact that the house was struck by lightning and destroyed in 1853 has fueled the haunted narrative.

[13]Oscar Sherwin, Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor (New York: The Century Co., 1931), 10.

[15]John Stedman, ed. The Norwich Jubilee. A Report of the Celebration at Norwich, Connecticut on the Two Hundredth Anniversary of the Settlement of the Town (Norwich: John W. Stedman, 1859), 90.

[16]George Washington to Jedediah Huntington, October 16, 1783, Papers of the New London County Historical Society.

[17]Norwich Committee of Correspondence Papers, New London County Historical Society.

[19]Peter Force, American Archives: Containing a Documentary History of the English Colonies in North America, from the King’s Message to Parliament of March 7, 1774, to the Declaration of Independence by the United States. Fourth Series (United Kingdom: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1837), 630-631.

[20]Mary Perkins, Old Houses of The Antient Town of Norwich 1660-1800 (Norwich: Press of The Bulletin Co., 1895), 249-250.

[21]Norwich Committee of Correspondence Papers.

[22]Samuel Adams to the Norwich Committee of Correspondence, July 11, 1774, in A Historical Discourse Delivered in Norwich, Connecticut, September 7, 1859, at the Bi-Centennial Celebration of the Settlement of the Town, ed. Daniel Coit Gilman (Boston: Geo. C. Rand and Avery, City Printers, 1859), 104.

[23]Christopher Leffingwell to William Phillips, August 1774, Massachusetts Historical Society, Series 4 Vol. 4, 45-46.

[24]Jedediah Huntington to the Boston Committee of Correspondence, April 1775, Norwich Committee of Correspondence Papers.

[25]New London Committee of Correspondence to the Norwich Committee of Correspondence, April 28, 1775, Norwich Committee of Correspondence Papers.

[26]The Committee of Correspondence Norwich to George Washington, August 7, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0169; original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 1, 16 June 1775 – 15 September 1775, ed. Philander D. Chase (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1985), 262–264.

[27]Jim Lampos and Michaelle Pearson, Revolution in the Lymes: From the New Lights to the Sons of Liberty (Charleston: The History Press, 2016), 43.

8 Comments

Dayne, thanks for a well written and researched article on the Sons of Liberty in Connecticut, particularly its early activities. It is an often misunderstood organization and its role in creating the political environment for the Revolution is usually given little credit.

Ken, thank you very much for your comments. It’s important that we understand how these early movements greatly shaped our political motives back then and how it influences us today.

A couple of years ago I emailed the Norwich Historical Society asking what happened to the Benedict Arnold birth house and when. The reply was they had no information in their files to answer that question. Just out of curiosity what is your source for the house being struck by lightening in the year you mentioned? Your article is the first time I have seen such a claim.

Hi Steve, thank you for your comment. Believe it or not, it’s possible that Arnold’s homestead was struck more than once by lightning; historian Frances Caulkins has documented it and we have other records and artifacts from the old house in the Leffingwell House Museum of which I’m President of the Board. We know that upon being struck by lightning it was ultimately destroyed in 1853 – I personally am usnure of the extent of the damage it initially suffered. A new foundation for a future house on that property wasn’t constructed until 1895 and that’s when the original key to the Arnold homestead was discovered. The key was donated to the Leffingwell House Museum in the 1960s. Hope this helps.

What is the specific source of the Caulkins Information? Also the destruction of the house in 1853? Would also appreciate seeing the records on the Arnold House in the records of the Leffingwell Museum. You can email me at da*******@co*****.net.

I read your article with great interest especially the section on Benedict Arnold. While you immediately painted Arnold as the “infamous traitor” and left the impression he was evil from the beginning because of his smuggling activities, etc. John Hancock was a bigger smuggler but I’ve never seen anyone imply he was evil. It’s worth noting the perception of smuggling in the 18th century was different than it is today. You glossed over the difficulties Arnold had in 1775 caused by the deliberate slandering he received from Easton, Major John Brown, and their supporters. To my knowledge the History of the Second Foot Guard never implied he was evil during his time with them. Arnold’s father’s alocholism is often used as an explanation for Arnold’s later behaviour. It’s not true. Many of us have had alcoholic parents and we turned out fine. Arnold was a traitor without question. He was vilified for his actions by Americans. If the British had used his skills (they didn’t), we would still be singing God Save the Queen and I often wonder if Arnold would have been considered a hero rather than a traitor. There are two sides to every story. Thanks for listening.

Thank you for your comment, Pip. Arnold is always a fascinating topic of discussion though I will clarify that not one person is ever “evil from the beginning” – it was never my intention to suggest otherwise. Arnold’s history is tragic, complicated, and crucial to understanding the nature of why he turned traitor in the first place; his father’s alcoholism and family shame is only a part of it and I would argue that there are far more substantive reasons for why he was pushed to the decision he made. His troubles with Easton, John Brown, and Moses Hazen would make for a riveting discussion too – perhaps another article! I appreciate the insight and thank you for reading.

Spectacular research Dayne. You would have been a member of the Sons, I suspect!