French naval officer La Pérouse (Jean Francois de Galaup, Comte de la Pérouse) was one of many who actively supported the American Patriots in their war for independence from Britain. La Pérouse’s assignments included patrolling the North Atlantic where he directed the capture of numerous British merchant vessels.[1] His early 1781 outbound voyage from France to Boston brought Gen. George Washington a supply of much-needed money and official strategic correspondence from the French court.[2] In 1782 La Pérouse commanded an Arctic raid on the commercial interests of Britain. His destruction of the British trading depots on Hudson Bay was very much a part of America’s Revolutionary War.

Once large-scale combat with the British erupted in the Boston area in the spring of 1775, Americans were buzzing with ways to weaken and destroy the British presence in North America and abroad. An armed attempt by Gen. Richard Montgomery and Benedict Arnold to conquer neighbouring British Canada ended with the failed assault on Quebec. In early spring 1776 a diplomatic approach to win the hearts and support of Canadians and the British colony for the American cause was spearheaded by Benjamin Franklin. This attempt also failed. Other leading American minds proposed weakening the British economy by capturing their merchant vessels thereby destroying their trading networks and skyrocketing their naval insurance rates.[3]

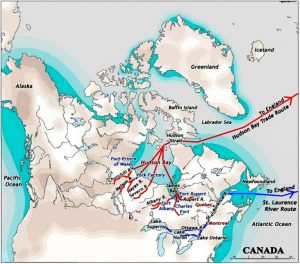

The majority of delegates to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia approved the Eastern Navy Board’s plan to attack the Hudson’s Bay Company’s (HBC) ships and trading forts. In April 1779 the Marine Committee of the congress communicated to the navy board, “Your design of sending a force to intercept the Hudson Bay Company Ships and perhaps to surprize and carry their factory meets our approbation—this Committee as well as your Board have had it often in contemplation; we therefore approve of the proposition made by the owner of a Privateer of twenty Guns, and agree that the Boston, instead of the Providence, shall be join’d with her and sent on the expedition above mentioned.”[4] The approval granted by the congress was not acted upon.

Both John Adams and Benjamin Franklin were aware of Britain’s lucrative fishing, whaling, and fur industries in the North Atlantic and Hudson Bay.[5] Franklin, after assuming his diplomatic role in Paris, prodded American privateer John Paul Jones to be on the lookout for HBC supply and trading vessels with their rich cargoes.[6] In this regard, it is also highly likely that Franklin, who worked closely with French foreign minister Charles Gravier, Count of Vergennes, sought the assistance of the King of France and his naval ministers. The HBC, anticipating hostilities on the high seas, requested British Admiralty convoy protection. A variety of British warships guarded the company’s merchant vessels that crossed forth and back through privateer-infested waters starting in 1778 through 1782.[7]

La Pérouse’s interest in Britain’s trading activities on Hudson Bay went back at least two years before he conducted his successful raid. In 1780 he proposed to a high-ranking naval compeer that the British on the Bay should be vanquished. His replacement plan called for French forts to be staffed by hardy Frenchmen from St. Pierre and Micquelon, the fishing islands just off the south coast of Newfoundland.[8] This plan, however, did not receive any immediate, overt royal support.

Paradoxically, La Pérouse’s chance to earn future royal accolades was jump-started following a major French naval defeat in the Caribbean in April 1782. Although he had earlier shared in several naval victories, it was British Adm. George Rodney’s victory in the Battle of the Saintes that put fresh wind in Pérouse’s sails. He joined the battered French squadron as it regrouped at Cap-Francois (Cap-Haitien, Haiti). During refitting and command restructuring efforts, Louis-Philippe de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil took command of the battered French Atlantic fleet. Together Vaudreuil and La Pérouse enacted a highly secretive retaliatory strike against the British establishments on Hudson Bay.[9] In late May 1782 La Pérouse set out with three warships, Sceptre, Astree, and Engageante, all under his command. His sailing orders directed him five thousand miles northward to Hudson Bay in an attempt to capture British trading vessels and destroy their bayside depots.

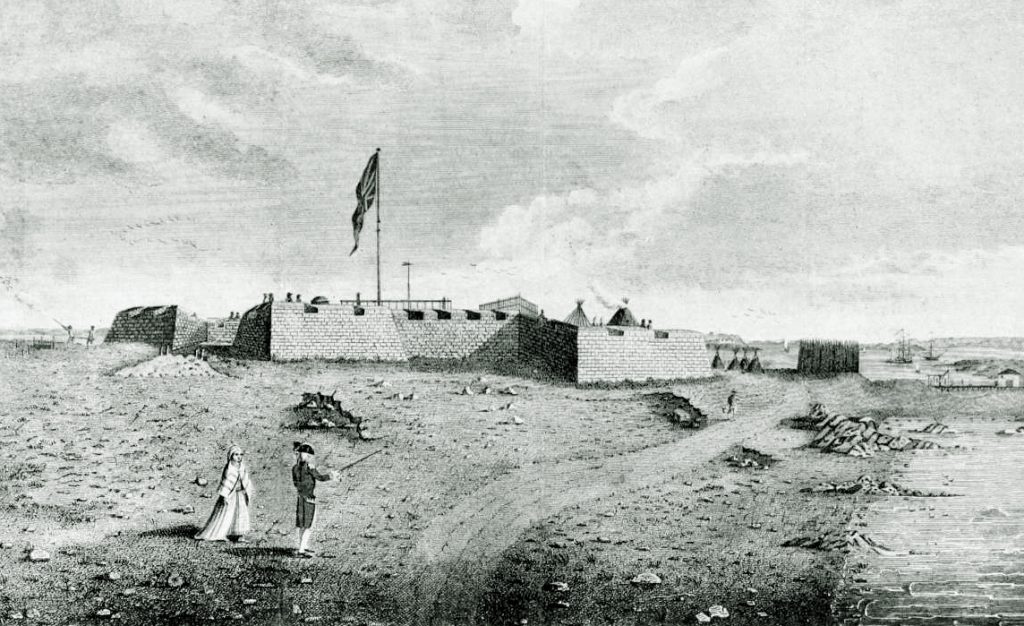

By early August 1782 La Pérouse’s warships were anchored very close to British-owned Churchill Fort (Fort Prince of Wales). His ship of the line, Sceptre, carried seventy-four cannon and several hundred troops and crew. The two companion French frigates carried additional troops, cannons, attack guns, mortars, and bombshells.[10]

Churchill Fort was built at the mouth of Churchill River located about midway along the western Arctic coastline of Hudson Bay. It was operated as a military and trading complex by the HBC headquartered in London, England. The site’s largest structure was a fifty-year-old star-shaped, massive fortress enclosed by a fifteen foot thick parapet sheathed in cut limestone blocks. Its surrounding rampart was pierced with forty cannon of various calibre.[11] By its outward appearance the fort could easily withstand a sizable attack, but the thirty or so manual laborers within its walls lacked military experience, artillery training, and courage.

On August 9, 1782 a small French naval force disembarked into longboats and rowed towards the fort. In the absence of any visible defensive activity, some officers along with marines boldly landed, marched forward and demanded entry. The gates were opened and its governor, Samuel Hearne, after a short parley, surrendered the fortress without a shot being fired.[12] The British commander and most of the workers were immediately taken as prisoners and herded onboard the anchored warships. The French flag was hoisted over the depot and most of its valuables were stripped by August 11. Larders were emptied and victuals, including the fort’s horses, were shuttled back to the ships to replenish their dwindling food supplies. The French loaded onboard many valuable prizes including large quantities of luxurious peltries. Before the attackers departed, the cannons were destroyed, huge gaps were blown in the stone walls and finally all the wooden structures and the powder magazine were torched.

La Pérouse’s fleet then sailed southeastward about one hundred fifty miles to the company’s principal post, York Fort (York Factory). This larger but less substantial armed depot was located very near the mouth of the Hayes River. The shallow, shoal-filled bay downstream from the fort necessitated a water and ground assault from a landing several miles distant. The enemy’s threatening appearance was first reported by the crew on August 20 to Capt. Jonathan Fowler, Jr., master of the anchored HBC’s supply vessel Prince George III. On the evening of August 21 several hundred French troops, their officers and some artillery were loaded into longboats. To reach York Fort the attack flotilla rowed, just beyond Fowler’s nine pounder’s cannon shots, into the nearby mouth of the Nelson River.[13] After finding a suitable landing the advancing troops made a long, difficult overland march through extensive drowned marshlands and small woods. Upon reaching the fort the following morning with an attack force of about seven hundred, a leading French officer demanded entry to the fort. Its infirm chief, Humphrey Marten, later recorded, “Before this I had hailed them and told them to halt. At first they took no notice but on my acquainting them that if they did not halt I should be obliged to fire at them they halted. I demanded a parley which was granted. They deliver’d a letter sign’d La Pérouse & [Major] Rostaing offering us our lives & private property but, threatening the utmost fury should we resist. On which I delivered terms of Capitulation which being in the main [were] agreed to; upon Honor I delivered up the Fort. They informed me Churchill was taken [earlier] and blown up.”[14]

A second eyewitness within York Fort later reported in a letter published in a 1782 London newspaper:

About 10 o’clock this morning [August 22, 1782] the enemy appeared before our gates; during their approach a most inviting opportunity offered itself to be revenged on our invaders by discharging the guns on the ramparts, which must have done great execution; but a kind of tepid stupefaction seemed to take possession of the Governor [Humphrey Marten] at the time of the trial and he peremptorily declared that he would shoot the first [company] man to fire a gun. Accordingly, as the place was not to be defended he, resolving to be beforehand with the French, held out a white flag with his own hand, which was answered by the French officer’s showing his pocket-handkerchief.[15]

The majority of York Fort’s hundred or so workers were added to the HBC prisoners already on board the French vessels. Those remaining were ordered onto the Severn, one of the company’s single-mast sloops commandeered earlier. The seized trading complex was torched, but not before an officer ordered a tent-like shelter to be constructed nearby. His troops then stocked it with large quantities of trade guns, powder, shot, blankets, clothing, food, etc. This humanitarian act by the French provided a small supply of survival goods for the benefit of the surrounding native families who were being decimated by an outbreak of smallpox.[16]

The remaining company posts further southeast (Severn, Albany, Moose, etc.) were not destroyed because they were smaller and mostly dependent on York Fort. La Pérouse had concluded that because his ships had lost their anchors in a recent storm, and more than three hundred of his crew were ill, he would not execute any further strikes.

Following the destruction of the two largest bayside HBC trading facilities, the three French warships sailed out of Hudson Bay and through the ice-clogged Hudson Strait. During their outward voyage one of the warships towed the Severn which was crammed with prisoners. While enroute on board Sceptre, prisoner Hearne’s polite mannerisms, intelligence, and accomplishments greatly impressed La Pérouse as they dined together at the officers’ table. Subsequently Hearne was granted his freedom and was ordered onto the Severn. His release was conditional on his pledge that once in London he would publish his manuscript travel journal that detailed his 1770-72 year-and-a-half-long overland trek to the Arctic Ocean via the Coppermine River.[17]

The Severn was subsequently untethered near Resolution Island just off the south eastern tip of Baffin Island. About thirty HBC prisoners, including Hearne and the crew, began their unplanned, risky voyage of just over four thousand miles across the cold North Atlantic to London via the Scottish Hebrides Islands and North Sea. The remainder of the British prisoners onboard the two French frigates, including Humphrey Marten from York Fort, were transported to Brest, France, and held as prisoners of war.[18]

Once the Severn anchored on October 18, 1782 in Stromness’ harbour in northern Scotland, Hearne sent off his first correspondence to the HBC headquarters. Foremost in his letter would have been his eyewitness account of the devastation executed on the Bay’s two largest depots by the French naval force.[19]

However, two very valuable British prizes escaped capture. La Pérouse’s force failed to outsmart two highly skilled and experienced HBC captains whose vessels were very close by during the pillaging and destruction of the trading posts. Capt. William Christopher was in charge of the inbound, cargo-laden Prince Rupert III, a 200 ton frigate. He first spotted the enemy’s fleet as he neared Churchill Fort.[20] About the same time, the French spotted Christopher’s approaching vessel and a frigate was dispatched to chase and capture Prince Rupert. The HBC captain was very familiar with the reefs and shallows along the bay’s western shore. He used his experience in these dangerous waters to out-distance the pursuer’s cannon shots and with the coming of nightfall he escaped. After the chase Christopher continued northward about one hundred miles and hid out in Knapp’s Bay until August 27. Presuming the enemy vessels were long gone he then sailed back to Churchill Fort and sounded his customary approach signal. When it went unanswered, Christopher immediately left the fort’s charred remains behind, turned his cargo-rich ship about and headed back to his company’s London headquarters.[21]

Jonathan Fowler, Jr., the senior captain of the second large vessel, King George III, faced a similar threat. On August 25 his crew was just finishing unloading cargo from the ship’s hold when the enemy squadron was spotted steering towards York Fort.[22] There was an immediate rush to get all of the inbound supplies offloaded and transferred to the fort. Simultaneously, boat crews from the fort quickly transferred to Fowler’s care the season’s huge collection of valuable fur bales, fresh water and food supplies. Using the cover of darkness to help elude the French threat, Fowler skillfully guided his loaded outbound vessel unscathed through numerous rocky shoals and shallows and started his homeward voyage to London.[23]

A third HBC captain, George Holt, didn’t have as much luck escaping the French. Holt and his crew of twelve men had been busy working their old, 70-ton sloop, Charlotte, on a remote bayside northern trading assignment while La Pérouse’s forces were busy destroying the company’s forts in the south.[24] Holt, on his return voyage to Churchill Fort, was unaware that Captain Christopher had hid from the French in Knapp’s Bay and headed south only days earlier. Total shock would have gripped Holt when the blackened ruins of his home base, Churchill Fort, came into view. Faced with life and death survival concerns, including shelter, food, clothing, and the coming winter, Holt with his crew determined at once to set sail in their aged sloop for company headquarters in London. The desperate crew must have braved many life-threatening challenges as they made their thirty-five-hundred mile voyage across the cold, stormy bay and north Atlantic. Luckily they overcame the dangers and on October 18 they successfully anchored their tiny vessel in England’s southwestern port of Plymouth.[25]

Holt had defied the odds of reaching his homeland and surely thanked the Almighty for his safe arrival. Immediately he sent off a dispatch to company headquarters in London. His account would have been the first received that described the burned out ruins of Churchill Fort. He surely also included in his missive the horrors of their daring voyage and the dreadful condition of his emaciated, scurvy-ridden crew.

Holt anticipated the presence of enemy privateers on the final leg of his voyage from Plymouth to London and therefore requested his company arrange a British Admiralty escort. On November 15 Holt and his crew were part of a London-bound convoy under the protection of His Majesty’s twenty-eight gun warship Nemesis.[26] Nearing the Isle of Wight in darkness, and while slightly ahead of his naval escort, two 4-pound cannon shots across his bow fired from French privateer Capt. James Roveau’s twelve-gun brig, ending Holt’s freedom. He and his crew were soon prisoners of war and the Charlotte was claimed as a prize after it anchored at Le Harve, France.[27]

Holt, from his detention quarters in Bolbec, France, requested his employer to pursue a release of himself and his crew. Come December 1, and still a prisoner, Holt penned an apologetic plea to his captor’s friendly American diplomat in Paris, Benjamin Franklin. “The Libty. I take in writing is, to solicit your Friendship; to gain me a pass or a exchange for me to go to England.”[28] Holt hoped by mentioning his earlier friendship with some of Franklin’s lady friends in Paris he might leverage some assistance. He desperately wanted to get safely back home to his wife and family in London whom he hadn’t seen for four years. Because a preliminary peace between the United States and Britain had recently been concluded, it is unknown if Franklin was of any help. Later HBC correspondence with Holt indicated his company would cover the costs of getting everyone back to Britain on the condition the captives honoured their existing contracts and returned to Hudson Bay as soon as possible.[29]

In summary, Vaudreuil’s and La Pérouse’s planned raid on the largest British-owned facilities dotted along the icy coastline of Hudson Bay fulfilled the aspirations of two countries. The French officers received their accolades from their king and America. News of their success was welcomed in Boston and Philadelphia in early December 1782.[30]

After La Pérouse anchored his ice-battered warship, Septre, in the Spanish port of Cadiz on October 13 he reported to King Louis XVI and his ministers. He stated he had inflicted damages on the British estimated to be ten to eleven million livres.[31] His successful siege and humanitarian acts earned him much royal praise, an increase in pay and pension, and an illustrious promotion. These rewards came with a huge debt borne mainly by his crew. They had suffered from hunger, scurvy, multiple illnesses, and over one hundred deaths, including fifteen men who drown when their longboat overturned in stormy waters in front of York Fort. La Pérouse was reprimanded, however, for his kindness and release of some of the British prisoners. He was praised for his thoughtful generosity shown to the Native families who were becoming dependent on the supplies of the British bay-side forts.

Upon receiving news of the loss of Churchill and York Fort, rebuilding plans were immediately formulated by the HBC’s governor and committee. The damages did not bankrupt the company but yearly dividends were not paid to their stockholders for several years. There is no agreement in the historiography of the raid regarding the company being compensated for its wartime losses. Indirectly, it was the indigenous population that experienced the greatest loss. There was already widespread suffering and fatalities among the native peoples surrounding the Bay. Their hardships were further exacerbated by the American planned and French executed revenge on the Bay.

[1]Dictionary of Canadian Biography (DCB), www.biographi.ca/en/bio/galaup_jean_francois_de_4E.html, accessed April 2, 2020.

[2]“Comte de Rochambeau to Gen. Washington, Feb. 11, 1781,” National Archives, Founders Online (NAFO), founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-05033, accessed April 2, 2020.

[3]“Samuel Chase to George Washington, Jan. 12, 1776,” NAFO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-03-02-0203, accessed April 2, 2020. Chase was a close friend of Washington’s who later became a Supreme Court justice.

[4]“Marine Committee to Eastern Navy Board, April 19, 1777,” Committee of the Second Continental Congress; Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1778-1789, 12: 356.

[5]“State of Trade with the Northern Colonies, 1-3 November 1768,” NAFO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-15-02-014, accessed April 2, 2020. On June 1, 1780, Adams sent a notice to the President of Congress about the expected outbound sailing date for the HBC ships. He learned this information from a May issue of a British newspaper.

[6]“Benjamin Franklin to John Paul Jones, July 8, 1779,” NAFO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-30-02-0044, accessed April 2, 2020.

[7]Norma J. Hall, Northern Arc: The Significance of the Shipping and Seafarers of Hudson Bay, 1508-1920, Doctoral Thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland, February 2009, 416-418.

[8]A copy of La Pérouse’s 1780 plan is in the Archives Nationales, Marine, in Paris. See an English translation at http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/52/laperousemanuscript.shtml, accessed April 2, 2020.

[9]Vaudreuil, before leaving France, was probably briefed by the French Ministry of Ports and Arsenals regarding Le Pérouse’s interest in eliminating the British presence on Hudson Bay. Vaudreuil assumed command of the French fleet after Commodore Comte de Grasse and his flagship, Ville de Paris, were captured by the British in the Battle of the Saintes. La Pérouse and Vaudreuil probably harboured revengeful feelings over their recent defeat in the Caribbean, their country’s earlier loss of French Canada to the British in 1763 and their forefathers’ exclusion from trading on the Bay as dictated by the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht.

[10]Captain Christopher recorded in his ship’s journal that one of the enemy vessels appeared to be missing its foremast. This damage was likely inflicted earlier by the British in the Battle of the Saintes. See Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Winnipeg, Manitoba (HBCA), C.1/904, August 11, 1782, 31.

[11]David Grebstad, “The Guns of Manitoba: How Cannons Shaped the Keystone Province, 1670-1887,” Manitoba HistoryNo. 72 (Spring-Summer 2013), 3.

[12]There are multiple accounts of Hearne’s bloodless surrender of Churchill Fort. See DCB, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hearne_samuel_4E.html, accessed April 2, 2020.

[13]See Jonathan Fowler, Jr.’s ship journal, HBCA, C.1/386, 26, August 22,1782.

[14]See 1782 York Factory Post Journal, HBCA, B.239/2/81, 3.

[15]Edward Umfreville, The Present State of Hudson’s Bay:Containing a Full Description of that Settlement, Printed for Charles Staker, 1790,126-27, (free online Google eBook).

[16]Matthew Cocking’s 1781-82 York Fort journal contains multiple references to the smallpox epidemic that had reached Hudson Bay by summer 1782. Cocking’s journal, HBCA, B.239/a/80, can be viewed online by conducting a Keystone Archives – Advanced Search of the Archives of Manitoba at http://pam.minisisinc.com/pam/index.html, accessed April 2, 2020.

[17]In 1787 the HBC allowed Hearne the opportunity to ready his travel journal for printing. An edited version, A Journey from Prince of Wales’ Fort in Hudson’s Bay to the Northern Ocean,was published posthumously in 1795.

[18]DCB, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/marten_humphrey_4E.html, accessed April 2, 2020.

[19]Hearne’s letter, written at Stromness dated October 18, 1782, was read at HBC headquarters on Nov. 13, 1782. See Foul Copies of Governor and Committee minutes, HBCA, A.1/141, 54.

[20]Captain Christopher, after he observed the three large ships ahead of him in the distance, made the following note in his ship’s log: “made the Ship [Prince Rupert III] Clear for Engaging [in battle] & Supposing them (as we very well might) to be Enemies one of them seem’d to have lost her foretop mast.” HBCA, C1/901, 31.

[21]Captain Christopher’s Prince Rupert III ship’s log, HBCA, C.1/904, 38.

[22]Captain Jonathan Fowler, Jr.’s King George III ’s ship’s log, HBCA, C.l/386, 26.

[24]HBC London Correspondence Book Outwards,1767-1795, Microfilm Series I, Reel #38 – F.77, A6/11, page 102.

[25]Ibid., reverse of page 2. The HBC’s reply letter to Holt dated October 22, 1782, acknowledges Holt’s arrival on October 18 at Plymouth, England.

[26]Ibid., 83. A letter dated December 6, 1782, to Philip Stephens, Esq. (Secretary of the British Admiralty) from Samuel Wegg (HBC Governor & CEO) summarizes Holt’s voyage and mentions the HMS Nemesisescort for the Charlotte from Plymouth to London.

[28]NAFO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-38-02-0298,accessed April 2, 2020.

[29]Foul copies of Governor and Committee minutes, HBCA, A.1/141, Wednesday, November 6, 1782, 52, records: “the committee will apply for their protection [from impressment and return to London] on their assurance of continuing in the Company’s [contracted] Service [at their posts on Hudson Bay].”

[30]“James Madison to Edmund Randolph, December 10, 1782,” NAFO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-05-02-0166, accessed April 2, 2020. “George Washington to Bartholomew Dandridge, December 18, 1782,” NAFO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10234, accessed April 2, 2020. News of La Perouse’s august success in Hudson Bay was received and quickly shared in America.

[31]NAFO, founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-05-02-0166, footnote 13; accessed April 2, 2020. The note reads, “La Pérouse estimated that he had destroyed or captured property worth between ten and eleven million livres. The company acknowledged a loss of from seven to eight million livres … or half a million sterling.”

One thought on “Revolutionary Revenge on Hudson Bay, 1782”

Thank you. Learned something new.