Their feet were leaving noticeable imprints in the grassy field. It was another two hundred yards to the hedgerow, and then a steep climb up the narrow footpath that snaked around the rising slope of hill in front of them. If they could make it without injury, perhaps there was a chance to dig in and make a stand against the coming enemy forces. And come they did. Two large columns of marching soldiers, one dressed in bright blue coats trimmed with red and tall brass-fronted caps, and another clad in red coats and diced highland bonnets. The spot of about a half dozen houses where two county roads intersected had provided a point of interest where both armies could mark their positions. The mixed units of Virginian continentals and Gloucester County militiamen were now on the hill, known as the mount, in Mount Holly, New Jersey. They numbered only a few hundred. Their eyes fixed on the 2,400 Hessian grenadiers, jaegers, and Scots highlanders who wanted one thing: the town behind the outnumbered American force. It was December 23, 1776, and the American cause had reached its darkest hour.

Histories of the Ten Crucial Days period of the Revolutionary War give ample coverage and critical analysis to how dire the situation was for George Washington’s fleeting Continental army. Having been reduced from some twelve thousand soldiers prior to the New York campaign earlier in the year to about three thousand by December, the very conception of a United States of America hung in the grasp of a band of brothers nearly broken from repeated defeats. Washington was faced with no shortage of crises: about two thousand of his soldiers were either sick with smallpox or had lost the will to fight; the remaining twenty-six hundred were severely under-equipped with winter clothing—and many lacked any sort of covering for their feet; munitions were low and food had to be foraged from the local population. There also remained the looming specter of dissolution of the army. Many of the enlistments of his men were set to expire on January 1, and Washington was well aware that nothing in the last few months had given the army a moment to celebrate, much less to spark their optimism in continuing the long fight. Indeed, the times tried many of the men’s souls. And as he weighed all these challenges, the American commander kept his eyes fixed across the Delaware River to the British garrison at Trenton.

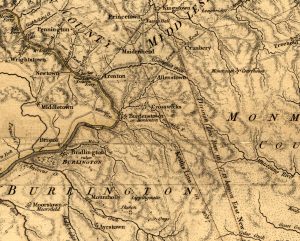

What is often left out of the grand narrative is how a handful of smaller pivotal skirmishes south of Trenton in the days before the attack played into Washington’s success. British commander-in-chief William Howe had sent Gen. Charles Cornwallis after Washington upon the fall of the last American fortification along the Hudson River in November. The Americans made it across the Delaware, and promptly removed all boats to their side of the river before Cornwallis arrived. Based on daily reports from deserters falling into their camp, the British determined that Washington was through, and with winter approaching, the decision was made to place a string of garrisons across New Jersey to keep the rebels at bay and await the spring to move on Philadelphia. The British command remained in New York, but Cornwallis was placed at New Brunswick with a sizable amount of reinforcements and supply stores. Ahead of him, pointing westward like a spear, were several divisions of Hessian and mixed-unit troops. At the tip of this spear, in Trenton, was Col. Johann Rall in command of about fifteen hundred Hessians and a small mixture of British regulars. Col. Carl von Donop had placed Rall at Trenton while he sought a spot further south to station the bulk his forces, an estimated twenty-four hundred troops, a number far too many to fit in the small town of Trenton. Donop first stopped at Bordentown, about eight miles south of Trenton along the Delaware, but here, too, his army proved to be too large to quarter within its streets. He then decided to divide portions of his troops among Bordentown, Crosswicks, and Black Horse, the latter two small hamlets drifting further south from Trenton. Black Horse (present-day Columbus) lay over five miles south of Bordentown, and about eight miles northeast of Mount Holly. With this arrangement, the British army had garrisons from Perth Amboy along the Raritan Bay west to New Brunswick on the Raritan River, and then west from Kingston to Princeton to Trenton. And now with Donop’s forces spread out south of Bordentown, their presence expanded into nearly all central New Jersey.

One of Donop’s officers in the jaeger corps, Capt. Johann Ewald, recorded what has become an invaluable source of information for the events that followed. Ewald kept a diary of the daily movements and skirmishes and described making time each evening to detail the events of the day while others slept or held watch in camp. Ewald wrote:

On the 13th [December] I went on a patrol beyond Slabtown toward Mount Holly with one hundred men, partly Scots and jaegers, where I ran into an enemy party which had driven together several hundred head of cattle. I attacked them, captured several men, and took some forty head of oxen from the enemy. I learned that General Mifflin had crossed the Delaware with one thousand men and had taken his position at Mount Holly, in order to attack the left flank of the army if Washington should cross the Delaware. I reported this at once to Colonel Donop, who for a moment was tempted to drive Mr. Mifflin away . . . . On the 19th Colonel Donop ordered me to accompany him to Black Horse to inspect the cordon of the left wing. The colonel took along Captain Lorey with twelve mounted jaegers, an officer and thirty Scots, and Colonel [Thomas] Stirling to reconnoiter the area of Mount Holly. We arrived at the village unhindered, where we obtained information that Colonel Griffin with two thousand men was stationed at Eayrestown, seven miles from Mount Holly. At eight o’clock in the evening we arrived back in Bordentown.[1]

As Donop confined himself to Bordentown, independent detachments of the Continental forces were indeed busy plotting how to spoil the comforts of the British and Hessian forces in the state. Col. Samuel Griffin, recently arrived from Virginia with a mixture of about two hundred artillerymen and volunteers, had met with Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam in Philadelphia. It was now mid-December, and the mood of the Continental encampment at Newtown, Pennsylvania, was one of anxiousness. Washington had yet to issue orders to move on Trenton, but there was clearly a sense of some decisive strike being worked out. Putnam indicated as much to Griffin and ordered him to gather what intelligence he could of the enemy’s positions south of Trenton, and remain committed to whatever opportunity presented itself.

As he came into New Jersey, Griffin, accompanied by a small number of Pennsylvanian regular infantry, rounded up another three hundred or so militia from Gloucester County and proceeded to march north through Haddonfield and Moorestown, reaching Mount Holly on December 21. His army numbered about six hundred, a far cry from the misinformation Donop had received days earlier. Griffin’s men quickly set about digging a redoubt on the mount, a slope of one hundred-thirty feet to the north of the town, and one on the hill south of the Rancocas Creek, adjacent to the iron works. Mount Holly was uniquely situated on the creek, giving it numerous access points to the waterway and allowing several mills and forges to operate in its early history. It boasted about a hundred buildings: a mixture of single-story wooden houses, more common two-story wooden colonial homes, a handful of taverns, a school, multiple churches and a meetinghouse. With his men finished their digging, Griffin allowed some of them to venture north of the town to hunt and scout for enemy patrols. In the meantime, the American colonel came down with a nasty infection, leaving him bedridden for much of what was about to occur. On their patrol, they ran into a forward post of enemy troops just north of Slabtown. Ewald recounted the movements beyond Mount Holly:

In the afternoon of the 22nd, I was reinforced with an officer and fifty grenadiers and took post at the Bunting house. This post was situated further on from Black Horse and Bustleton and consisted of a plantation lying upon a hill where the roads coming from Mount Holly and Burlington intersected. Toward the enemy I had woodland, through which these roads ran, and behind me was an extensive meadow . . . I had scarcely arrived at this post when the enemy appeared in the wood. I took the jaegers to reconnoiter him and to learn with whom I had to deal. I skirmished with the enemy, who, since I attacked him quickly withdrew toward Burlington with a loss of several dead and wounded. I pursued him for a short distance, and after I was certain of his retreat I returned to my post. One of my jaegers was killed and another severely wounded . . . No sooner had this skirmish ended than I heard heavy small-arms fire mixed with cannon fire in the vicinity of Black Horse or Slabtown. This firing caused me no little embarrassment because it was in my rear. I decided to investigate the firing and to fall upon the enemy’s rear during his own attack. I hurried as fast as I could; however, the enemy had already been driven back by the grenadiers with heavy losses. Colonel Donop ordered me not to return to the Bunting house, but to choose post in front of Black Horse.[2]

Lt. Col. Thomas Stirling, commander of the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment, had sent a few scouts southward from Black Horse toward Slabtown to find horses and any supplies the troops could gather. They halted at the Petticoat bridge that ran across the Assiscunk Creek, just north of the village. The American scouts promptly opened fire on the hard-to-miss British troops. As Ewald noted, a minor skirmish ensued; it appears the Americans successfully chased off the patrol, and then promptly fell back to Mount Holly. However, once word got to Stirling at Black Horse, there seems to have been a miscalculation over the number of Americans hauled up at Mount Holly. Back in Bordentown, it appears Donop was fixed on the notion that Griffin had a force of about two thousand men. From Ewald’s account, Donop was encouraged by Stirling and others to remove this southern threat to the garrisons. It was believed their forces were a good match for whatever Griffin had. Ewald also wrote that Donop was cautioned several times about pulling further south away from Trenton, but it appears the Hessian colonel favored taking Mount Holly for himself over the warnings of a possible attack by Washington. Donop gathered his entire force and proceeded southward to Slabtown. As this was happening, Griffin received an urgent letter from Washington’s adjutant general Joseph Reed on the evening of December 22. That same day, Reed had written the following to Washington:

Colonel Griffin has advanced up the Jerseys with six hundred men as far as Mount Holly, within seven miles of their [Donop] head-quarters at the Black Horse. He has written over here for two pieces of artillery and two or three hundred volunteers, as he expected an attack very soon. The spirits of the militia here are very high; they are all for supporting him. Colonel Cadwalader and the gentlemen here all agree, that they should be indulged. We can either give him a strong reinforcement, or make a separate attack; the latter bids fairest for producing the greatest and best effects. It is therefore determined to make all possible preparation today; and, no event happening to change our measures, the main body here will cross the river tomorrow morning, and attack their post between this and the Black Horse, proceeding from thence either to the Black Horse or the Square, where about two hundred men are posted, as things shall turn out with Griffin. If they should not attack Griffin as he expects, it is probable both our parties may advance to the Black Horse, should success attend the intermediate attempt. If they should collect their force and march against Griffin, our attack will have the best effects in preventing their sending troops on that errand, or breaking up their quarters and coming in upon their rear, which we must endeavor to do in order to free Griffin.[3]

The American commander in chief responded the next day with:

The bearer is sent down to know whether your plan was attempted last night, and if not to inform you that Christmas day at night, one hour before day is the time fixed upon for our attempt on Trenton. For Heaven’s sake, keep this to yourself, as the discovery of it may prove fatal to us; our numbers, sorry am I to say, being less than I had any conception of; but necessity, dire necessity will, nay must, justify my attack. Prepare, and in concert with Griffin, attack as many of their posts as you possibly can, with a prospect of success; the more we can attack at the same instant, the more confusion we shall spread and greater good will result from it.[4]

Donop was already mobile by the time Griffin received his orders from Reed, a happy stroke of coincidence whose effects would greatly benefit what the Continental army was about to do in Trenton. On the morning of December 23, a large body of Griffin’s men, no more than two hundred it seems, once again approached the Petticoat bridge north of Slabtown.[5] Their orders were to lure the Hessians to Mount Holly. It would only work if they did not fall back too quickly and avoided becoming encircled by the advancing enemy columns. Keeping Donop under the assumption that he was walking into a major engagement, the Americans had to time their deception just right. At first, the stand worked. The initial Hessian advances stopped when they drew heavy fire from the bridge. Within twenty minutes, the bulk of Donop’s forces gathered their ranks and moved forward in columns containing all of his twenty-four hundred troops. Clearly outnumbered, the Americans fell back to Slabtown before retreating south across four miles of meadows and low, swampy fields towards Mount Holly.

We know that there was a brief firefight on the hill next to the iron works on the south side of the Rancocas Creek, after the Americans fell back through the town with the Hessians in hot pursuit. However, new historical detective work has unearthed the very likely possibility that the Battle of Iron Works Hill was not the singular engagement in Mount Holly on December 23. In fact, a brief, and more intense fight might have taken place on the mount itself before the Americans retreated through the town. Clues in Ewald’s journal that our team of local historians have carefully pieced together indicate that Donop divided his forces to conduct a major assault on the mount. If Donop was under the assumption he was about to run into a force of two thousand American soldiers, this made sense. Ewald filled in the events that followed:

On the morning of the 23rd at five o’clock Colonel Donop set out toward Mount Holly with the 42nd Regiment of Scots, the two grenadier battalions, Linsing and Block, the twelve mounted jaegers under Captain Lorey, and my jaeger company. I formed the advanced guard, supported by Captain Lorey and a company of Scots . . . In the wood behind Slabtown we ran into an enemy party which took new position at a Quaker church lying on a hill at the end of the wood behind which the entire enemy corps was deployed. The colonel immediately ordered the Linsing Battalion to attack the hill on which the church stood. The Block Battalion was ordered to the left, and the jaegers with four companies of Scots under Colonel Stirling, moved to the right through the wood to cut off the enemy from Mount Holly or to gain mastery of the bridge across the Rancocas Creek, which intersects the town.[6]

Ewald made note of a Quaker church as they approached from the north. He incorrectly mentioned “the hill on which the church stood.” The building was located in front of the mount and sat adjacent to the old Slabtown road (which no longer exists). This is the route along which the Americans led Donop’s forces southward. We can forgive Ewald for mistaking its position on their approach.[7] A 1957 topographical map done by Burlington County shows an elevated ridge running just north of present-day Woodlane Road (which was then a wagon road running in an east-west direction and met the Slabtown road in a ‘T’ formation). It’s likely Ewald mistook the “hill at the end of the wood” for this ridge—as the ground would have been elevated on his approach. Nevertheless, the Hessian forces did see a thickly-treed hill behind the church. Further maps done by Ewald in 1776 and by British assistant engineer John Hills in 1778 accurately show the northern route of the Slabtown road as it divides into two directions, one leading west toward Burlington and the other running northeast directly to Slabtown (present-day Jacksonville), showing the approaches to Mount Holly both armies took.

The Americans looking down at Donop’s artillery and encircling columns did not last long. Recall, their orders were not to engage the far superior force, but rather to create a feint and lure the Hessians entirely into the town. It wasn’t long before the smaller forces abandoned the hilltop and scattered southward into the downtown corridor of Mount Holly. Sporadic musket fire went back and forth as the two armies chased through the streets. The Americans crossed the Rancocas Creek at the old causeway bridge (present-day Pine Street) and took up their fortifications to continue their ruse. Donop, thinking the bulk of the Americans were likely atop this second hill, placed his artillery on a northern flank, near the modern site of Top E Toy Street along Powell Road east of town. Coupled with the cannonade from this artillery position, and the encroaching fire of the grenadiers and jaeger corps, Griffin’s remaining men departed the iron works hill sometime overnight on December 24.[8] By the morning, they had moved on southwest to Moorestown. We are unsure how, but Donop was wounded during the day’s events and must have looked for lodging to tend to his wounds. The presence of a widow in town, whose identity remains hotly contested, seems to have comforted him—much to the peril of Colonel Rall at Trenton two days later.[9] Ewald wrote that it was Donop’s troops, not Rall’s, who were the ones plundering the liquor stores of an occupied town in celebration of Christmas—in this case, Mount Holly. The comfort his entire army felt in lodging at Mount Holly, the first town in which everyone could take quarters together, likely played a role in Donop’s passiveness. By the time word reached Mount Holly on December 26 of the events at Trenton, it was too late. It would take Donop at least a day to march the twenty-two miles through winter conditions. We may opine about how Trenton affected the outcome of the war, but I leave you with Johann Ewald’s own take on how the events at Mount Holly played the decisive role in Washington’s greatest stroke:

This great misfortune, which surely caused the utter loss of the thirteen splendid provinces of the Crown of England, was due partly to the extension of the cordon, partly to the fault of Colonel Donop, who was led by the nose to Mount Holly by Colonel Griffin and detained there by love . . . . Thus the fate of entire kingdoms often depends upon a few blockheads and irresolute men.[10]

Today, Woodlane Road cuts across the townships of Eastampton, Mount Holly, and Westampton from east to west, following the old wagon trail from 1776, drawing a clear line of where the two armies crossed paths as they approached Mount Holly on December 23, 1776. The site of where the Quaker church and road to Slabtown were located are hard to see in the modern era. The church was torn down sometime in the 1780s, and the only reference to it (aside from Ewald’s) comes from an 1859 article written by a local historian. A graveyard along Woodlane Road marks the site of the former church with a weak depression of the former road fading into the ground. Unfortunately for our efforts, a country club was built fifteen years ago over much of the meadow and swamp lands where the running engagement took place. Many of us can appreciate the enjoyment playing a round of golf brings. Unfortunately, this story is another example of a lost opportunity to explore and possibly excavate evidence of the engagement’s intensity and relevance to our history. While it is already the case that the Battle of Iron Works Hill receives far less credit than it deserves in playing a role in Washington’s capture of Trenton, we now have evidence that Mount Holly’s day-long engagement was a far larger battle than historians have previously thought. We hope in the years to come our little town receives its rightful place in our country’s history as aiding to the survival of American independence.

[This archaeological and historical detective work is the product of years of research and dedication by Gary Nelson and Eric Orange, founders of the Rev War Alliance of Burlington County, New Jersey, of which I am a member. It was under their encouragement that I took up the digital pen to write this brief overview of the engagement at Woodlane. Mr. Nelson is a military historian and Mr. Orange lives on the iron works hill.]

[1]Johann Ewald, Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal, 31, 34, National Archives online, archive.org/details/EwaldsDIARYOFTHEAMERICANWAR/page/n67.

[3]Joseph Reed to George Washington, Bristol, December 22, 1776, in William Bradford Reed,Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed: Military Secretary of Washington, Volume 1(Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1847), 271-272, books.google.com/books?id=OCJCAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA265&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[4]Washington to Reed, Camp above Trenton Falls, December, 23, 1776, ibid., 274.

[5]The Skirmish at Petticoat Bridge marker, www.revolutionarywarnewjersey.com/new_jersey_revolutionary_war_sites/towns/springfield_nj_burlington_county_revolutionary_war_sites.htm.

[7]It is telling that Ewald did not later correct his misjudgment of where the church was located on the Hessian approach. It is plausible that, in the heat of preparing an attack on the mount, his focus was elsewhere. This conclusion supports our belief that Donop had ordered a major assault, which is supported by Ewald’s description of how the army divided itself. It also explains, perhaps, why Ewald wrote very few details about what occurred during the battle. It wasn’t much of a fight; in the end, the Americans had achieved their objective. Donop’s entire army was nestled in at Mount Holly – too far from Trenton to reinforce Rall when trouble came.

[8]The Battle of Iron Works Hill marker, www.revolutionarywarnewjersey.com/new_jersey_revolutionary_war_sites/towns/mount_holly_nj_revolutionary_war_sites.htm.

[9]The identity of the “widow of Mount Holly” remains a topic of debate among historians. Local lore says that she was the widow of a doctor and possibly part of a spy network in Burlington County; therefore, she had motive to keep Donop quartered. Others have identified her as none other than Betsy Ross, though her late husband was not a doctor and there is no record of Ross being in Mount Holly.

12 Comments

Thank you, Adam! A really interesting and well-researched article about a diversionary engagement which, though included in Fischer’s Washington’s Crossing, I had entirely lost sight of. Are there groups in your area which conduct tours of these lesser known Rev War sites?

George,

Thank you for the read and your interest. Yes, Mount Holly will be holding their annual “Battle of Iron Works Hill Day” next Saturday, December 14th. I’ll be speaking at the Lyceum Museum on High Street at 12:30pm and there will be a walking tour to follow. For more info, feel free to contact the Rev War Alliance of Burlington County at:

re************@ya***.com

Thank you for this article.

My ancestor, Capt. John Mott of the 3rd NJ Continentals (not to be confused with Capt. John Mott of the Hunderdon militia),* lived just north of Mt. Holly near the Quaker church on land inherited from his father. While John was at Fort Ticonderoga at the time, his homestead and family were plundered by Hessian soldiers. (Inventory of Damages by the British, claim #229 & writings by his granddaughter.)There’s an interesting article, “The Battle of Iron Works Hill” in the Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society: Vol IV New Series, No. 1-4 (January-October 1919). William A. Slaughter author. I have a copy of that.

*see http://davidlibraryar.blogspot.com/2011/11/patrons-perspective-tracing-new-jersey.html for this confusion, something I need to write about as a follow up. It’s been a while since I delved into this, but I have some things to add to Larry Kidder’s article.

Steve,

Thank you for your interest and the outstanding linkage to the area! Huzzah!

Very nice article, Adam. I particularly like the maps and info on the sites today. I wholeheartedly agree that these encounters should be more widely known and I always appreciate learning more about them myself. Thank you.

Larry,

Thank you for the kind words and your continued contributions to our area’s history. I’ll be using more maps in our presentation next Saturday, December 14th at the Mount Holly Lyceum, if you can make it.

Cheers!

Interesting!

I’m curious what sealed the deal in deciding that the Woodlane meeting house was the site of the action, as opposed to the extant 1775 meetinghouse on High and Garden Streets. USGS Topo has it on a slight elevation from High Street, and it’s right on the edge of the original town, uphill and much closer to the creek.

Love reading about Jersey stuff!

Jason,

Thanks for the read and your interest. Our conclusion for the site of the church, aside from that 1859 article I mentioned, comes mostly from deciphering Ewald’s journal, i.e. the location of where the Hessians were located on their approach to Mount Holly. Considering that Ewald mentions a lone church on a hill, and not one situated in town, he provides us our first clue that this is not the meetinghouse on High/Garden Streets. Remember, the mount itself would have stood in the way of their approach to town if they were coming from the north. If we are to deduce that the church he saw is one located on the Slabtown Road, Ewald’s wording indicates the mount stood behind, not in front, of the church – meaning they had yet to put the mount behind them.

Second, Ewald notes that Donop ordered Stirling to wheel right and cut off the Americans before they reached the bridge over the creek. This would have been the Pine Street bridge, north of the Rancocas Creek, and the iron works hill where their second redoubt was. Ewald does not indicate their location, i.e. Stirling’s, to be among houses and buildings, but rather in an open environment and still approaching Mount Holly. As you noted, if they had been discussing the Meetinghouse, they would had already been within town.

Lastly, using maps made between 1776-78, we know where the Slabtown Road was located. If you study John Hills’s “Black Horse and Mount Holly” map from 1778, you’ll see he marks the site of the church, adjacent to the intersection of the road and the old wagon road (modern-day Woodlane Road). The Library of Congress’s website allows you to zoom-in to see this clearly. We also know, based on Ewald’s and Hills’s maps, that there were houses and buildings along the wagon roads out of the center of town. When the two armies raced down High Street from the mount, they would have been running through a semi-established neighborhood.

Thank you for your inquiry; I hope this explanation helps.

Great, informative read. Thank you.

Tony,

Thank you for the kind words, I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Cheers!

Thank You Mr. Zielinski. Your work was very thought provoking.

I had not been aware of a place called Bustleton located in New Jersey, as I always thought that Bustleton was a place indigenous to Lower Dublin Township on the Pennsylvania side of the River Delaware.

However, when viewing a Hessian Map: http://westjerseyhistory.org/maps/revwarmaps/hessianmaps/index2.shtml – it appears that there was also a Black Horse Tavern in Bustleton, Lower Dublin Pa., on a road leading nearly straight to an un-named Ferry (probably Dunk’s Ferry) and into Jersey.

This is almost on a straight line to Slabtown and the Black Horse Tavern on the Jersey side of the River. Perhaps its just coincidence?

There are several Revolutionary War Era Maps from the Hessian State Archives found at the West Jersey History Project:

http://westjerseyhistory.org/maps/revwarmaps/hessianmaps/

Just saying.

J.M.

Hi Joseph,

Thanks for the kind words and your inquiry. Likely, Ewald was mistaken when he wrote down Bustleton. It most certainly was not the province located across the Delaware River in Pennsylvania that he was referring to because of his location. Other maps of the era, including those done by British officers John Andre and John Hills, do not have a “Bustleton” in the vicinity of Black Horse (modern-day Columbus). And the link to the West Jersey map depository also does not turn up a manuscript with such a name listed in Burlington County in 1776.

As a local of the area, I am unaware of any dwelling by this name to have existed then. I could be wrong, and there might have been a small village of the same name located somewhere along one of the main wagon roads: too small to be listed on any map, but notable as a location point for a foreign field commander on the march. We simply don’t know for sure (as of now), but I’m confident to assert that in this particular case (much like the Quaker church I discussed), Ewald was mistaken and did not correct his error.

Thank you.